Complete guide to Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS: High Court and Sessions Court bail powers, grounds, procedure, case laws. Understand your bail rights today!

Table of Contents

What is Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS)- Special powers of the High Court or the Court of Sessions regarding bail?

When you’re facing criminal charges and a Magistrate denies your bail application, you’re not without options. Section 439 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (now Section 483 of the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023) grants special powers to the High Court and the Court of Sessions to grant bail even in cases where lower courts have refused. This provision serves as a crucial safeguard for personal liberty, allowing superior courts to exercise broader discretionary powers in bail matters without the limitations that bind Magistrates.

The significance of Section 439 CrPC/Section 438 BNSS lies in its expansive scope: these superior courts can grant bail in any case, including offences punishable with death or life imprisonment, modify conditions imposed by Magistrates, and even cancel bail previously granted. In Sundeep Kumar Bafna v. State of Maharashtra [(2014) 16 SCC 623], the Court held that an accused in custody can directly approach the Sessions Court or High Court for bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS without first approaching the Magistrate, thereby removing unnecessary procedural hurdles.

Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS): Understanding the legal provisions

Understanding the exact language and scope of Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) is essential for anyone navigating bail applications in superior courts. Let me break down each subsection to help you understand your rights and the court’s powers clearly.

Section 439(1)(a) CrPC (Section 483(1)(a) BNSS)- Power of the High Court and Sessions Court to Grant Bail

Here is what Section 439(1)(a) states:

“(1) A High Court or Court of Session may direct-

(a) that any person accused of an offence and in custody be released on bail, and if the offence is of the nature specified in sub-section (3) of section 437, may impose any condition which it considers necessary for the purposes mentioned in that sub-section.”

This provision empowers the High Court and Sessions Court to grant bail to any person in custody, regardless of the nature or gravity of the offence. Unlike Magistrates who face statutory restrictions under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, these superior courts have unfettered discretion to release accused persons on bail even in cases involving death penalty or life imprisonment. The phrase “may direct” indicates judicial discretion: the court must evaluate each case on its merits considering factors like nature of accusation, severity of punishment, character of evidence, and reasonable apprehension of witness tampering or accused absconding.

When the offence falls under the category specified in Section 437(3): meaning serious offences where there are reasonable grounds to believe the accused is guilty and they may commit further offences while on bail; the court can impose necessary conditions to ensure the accused’s presence during trial and prevent misuse of liberty. These conditions typically include restrictions on leaving the jurisdiction, regular reporting to police stations, surrendering passports, and avoiding contact with witnesses. The court’s power to impose conditions is derived from the necessity to balance personal liberty with public safety and the integrity of the criminal justice system.

In Ram Govind Upadhyay v. Sudarshan Singh [(2002) 3 SCC 598], the Supreme Court clarified that while granting bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, courts must consider the nature and gravity of accusations, the position of the complainant and the accused, the likelihood of the accused fleeing justice, and the possibility of repeating similar offences. The Court emphasized that personal liberty is paramount but must be balanced against society’s interest in ensuring effective investigation and trial. In Kalyan Chandra Sarkar v. Rajesh Ranjan [(2004) 7 SCC 528], the Court further held that the power to grant bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS should be exercised judiciously, keeping in mind that denial of bail amounts to deprivation of personal liberty, but granting bail in heinous offences may endanger society and the trial process.

Section 439(1)(b) CrPC (Section 483(1)(b) BNSS)- Power to Modify Magistrate’s Bail Conditions

“…(b) A High Court or Court of Session may direct that any condition imposed by a Magistrate when releasing any person on bail be set aside or modified.”

This provision recognizes that Magistrates sometimes impose bail conditions that may be excessive, impractical, or unnecessarily restrictive. The High Court and Sessions Court have the authority to review these conditions and either modify them to make them more reasonable or set them aside entirely if they’re found to be unjustified. For instance, if a Magistrate imposes a condition requiring the accused to deposit ₹10 lakhs as bail security when the accused’s financial capacity is limited, the superior court can reduce this amount to a reasonable figure.

In the landmark case of Moti Ram v. State of Madhya Pradesh [1978 AIR 1594], the Supreme Court categorically held that courts cannot reject a surety merely because the surety or his property is situated in a different district or state. Insistence on “local sureties”, especially when the accused hails from another region, is impermissible and discriminatory. The Court emphasised that the surety system must serve its purpose (ensuring the accused’s appearance) without being onerous or defeating the grant of bail. Wherever possible, sureties offered by relatives or friends should be accepted, and in appropriate cases, the accused may even be released on personal bond.

More recently, the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Mursaleen Tyagi vs. the State of Uttar Pradesh (Petition for Special Leave to Appeal (Crl.) No. 898 of 2023) reiterated that bail may be granted subject to onerous or stringent conditions only in exceptional circumstances and not as a matter of routine/ordinarily. The Court disapproved of practices that effectively make bail illusory by imposing impractical financial or other burdensome preconditions.

The power to modify conditions is particularly important when circumstances change after the original bail order. If an accused was initially prohibited from leaving the city but later needs to travel for genuine medical treatment or employment reasons, they can approach the Sessions Court or High Court under Section 439(1)(b) CrPC/Section 483(1)(b) BNSS to modify this restriction. This flexibility ensures that bail conditions remain proportionate to the offence and don’t become instruments of harassment or practical imprisonment despite being technically “on bail.”

First Proviso – Notice to Public Prosecutor for Life Imprisonment Cases

The first proviso to Section 439(1) CrPC/Section 483 BNSS states as below:

“Provided that the High Court or the Court of Session shall, before granting bail to a person who is accused of an offence which is triable exclusively by the Court of Session or which, though not so triable, is punishable with imprisonment for life, give notice of the application for bail to the Public Prosecutor unless it is, for reasons to be recorded in writing, of opinion that it is not practicable to give such notice.”

This proviso introduces a mandatory procedural safeguard for serious offences. Before granting bail in cases triable exclusively by Sessions Court (such as murder, dacoity, or rape) or offences punishable with life imprisonment, the court must give notice to the Public Prosecutor. This ensures that the prosecution has an opportunity to present its objections and concerns about releasing the accused. The notice requirement serves the important purpose of allowing the State to represent public interest and highlight any specific reasons why bail should be denied, such as potential danger to witnesses or likelihood of the accused fleeing.

However, the proviso recognises practical difficulties by allowing courts to dispense with this notice requirement in exceptional circumstances. If giving notice would cause unreasonable delay in urgent cases, or if the Public Prosecutor is unavailable despite reasonable efforts, the court can proceed without notice; but must record detailed reasons in writing explaining why notice was impractical. This exception prevents the notice requirement from becoming a tool for indefinite detention when the prosecution intentionally avoids receiving notice.

In the State of U.P. v. Amarmani Tripathi (2005) 8 SCC 21, the Supreme Court held that bail orders passed without giving notice to the Public Prosecutor in life imprisonment cases are liable to be set aside unless valid reasons are recorded for dispensing with notice. This judgment reinforced the principle that procedural safeguards cannot be bypassed without proper justification, as they protect both the accused’s right to be heard and society’s interest in ensuring serious crimes are properly prosecuted.

Second Proviso: 15-Day Notice for Sexual Offences Under IPC Sections 376, 376AB, 376DA, 376DB

The first proviso to Section 439(1) CrPC/Section 483 BNSS states as below:

“Provided further that the High Court or the Court of Session shall, before granting bail to a person who is accused of an offence triable under sub-section (3) of section 376 or section 376AB or section 376DA or section 376DB of the Indian Penal Code, give notice of the application for bail to the Public Prosecutor within a period of fifteen days from the date of receipt of the notice of such application.”

This second proviso was inserted by the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2018, following widespread public outcry over inadequate protection for victims of sexual violence. It creates an even stricter notice requirement for specific aggravated sexual offences – the court must give notice to the Public Prosecutor within 15 days of receiving the bail application itself. These offences include rape of women under 16 years of age [Section 376(3)], rape causing death or persistent vegetative state [Section 376AB], gang rape of women under 16 years [Section 376DA], and gang rape causing death or persistent vegetative state [Section 376DB] under the Indian Penal Code (now corresponding sections under the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita).

The 15-day timeline is mandatory and brooks no discretion; unlike the first proviso which allows courts to dispense with notice in impractical circumstances, this proviso contains no such exception. The stringent requirement reflects legislative intent to ensure that bail in heinous sexual offences is not granted hastily without proper scrutiny by the prosecution. The Public Prosecutor must be given adequate time to examine the case, gather necessary information about the victim’s safety concerns, and present comprehensive objections to bail.

In Bhagwan Singh v. Dilip Kumar @ Deepu @ Deepak [2023 SCC OnLine SC 1059], the Hon’ble Supreme Court quashed the Rajasthan High Court’s bail order in a case of a minor’s gang rape by the son of a sitting MLA and his associates. The Court held that bail orders in heinous sexual offences must reflect application of mind to the gravity of the crime, the accused’s influence, and the real possibility of witness/victim intimidation. A casual or cryptic order that ignores these factors is unsustainable, and courts must remember that such crimes constitute an onslaught on the dignity of womanhood.

In X v. State of Rajasthan & Anr. (2024 INSC 909), while upholding bail granted to the accused in a rape case, the Supreme Court emphasised the necessity of imposing stringent protective conditions to safeguard the victim and witnesses from any pressure or threat. The accused was directed not to enter the village/town where the victim resides and not to contact the victim or her family members in any manner till the trial is concluded. The judgment underlines that even when bail is granted, the balance must tilt towards ensuring the victim’s safety and the integrity of the trial process.

Section 439(1A) CrPC (Section 483(2) BNSS)- Mandatory Presence of Informant in Sexual Offence Cases

The Section 439(1)(A) CrPC/Section 483(2) BNSS states as below:

“The presence of the informant or any person authorised by him shall be obligatory at the time of hearing of the application for bail to the person under sub-section (3) of section 376 or section 376AB or section 376DA or section 376DB of the Indian Penal Code.”

This subsection, also introduced by the 2018 amendment, mandates that the complainant or informant (typically the victim or their family member) or their authorized representative must be present during the bail hearing in cases of aggravated sexual offences. This requirement ensures that the victim’s voice is heard in the bail proceedings, recognizing that sexual violence cases profoundly impact victims and they have a legitimate interest in bail decisions. The word “obligatory” makes this attendance mandatory, not optional: courts cannot proceed with bail hearings in these specified sexual offences without ensuring the informant’s presence.

The provision allows flexibility by permitting “any person authorised by him” to attend on behalf of the informant. This recognises that sexual violence victims may face severe trauma and may not be emotionally prepared to attend court proceedings where they might encounter the accused. The informant can authorize a family member, legal representative, or support person from a victim assistance organization to attend the hearing on their behalf. This balanced approach ensures victim participation while being sensitive to their psychological wellbeing.

What Happens If an Informant Doesn’t Appear at Hearing?

If the informant fails to appear at a bail hearing in the specified sexual offence cases despite proper notice, courts face a procedural dilemma. While Section 439(1)(A) CrPC/Section 483(2) BNSS makes presence “obligatory,” there’s no explicit guidance on whether the court can proceed without the informant or must adjourn the hearing. In practice, courts typically adjourn the hearing and direct investigating officers to ensure the informant’s presence or authorised representative’s attendance at the next date, recognizing that proceeding without mandated presence could render the bail order vulnerable to challenge. However, if the informant deliberately avoids attending despite multiple notices, courts may proceed with the hearing after recording reasons for the informant’s non-appearance.

Section 439(2) CrPC (Section 483(3) BNSS)- Power to Cancel Bail and Re-Arrest

The Section 439(2) CrPC/Section 483(3) BNSS states as below: s

“A High Court or Court of Session may direct that any person who has been released on bail under this Chapter be arrested and commit him to custody.”

This provision grants High Courts and Sessions Courts the power to cancel bail that has been granted under any provision of Chapter XXXIII CrPC/Chapter XXXV BNSS (which covers Sections 436-450 CrPC/Section 478 to 496 dealing with bail and bonds). Once bail is cancelled under this provision, the court can direct the accused’s immediate arrest and commitment to custody. This power acts as an important check on misuse of bail and ensures that liberty granted through bail doesn’t become a license to obstruct justice or endanger public safety.

The power under Section 439(2) CrPC/Section 483(3) BNSS is distinct from the power to refuse bail: cancellation of bail is a more serious step taken after bail has already been granted and the accused has been released. Courts exercise this power cautiously because it involves curtailing liberty that was previously granted after judicial consideration. The grounds for cancellation typically include: the original bail order was passed without proper application of mind or on incorrect facts; the accused is absconding or attempting to flee from justice; there’s evidence of witness tampering or intimidation; the accused has committed another offence while on bail; or fresh evidence has emerged that materially changes the complexion of the case.

In Dolat Ram v. State of Haryana (1995) 1 SCC 349, the Supreme Court laid down that bail once granted should not be cancelled in a mechanical manner and the party seeking cancellation must show either that the order granting bail was perverse or that the accused has abused the concession of bail. The Court emphasized that mere filing of an application for cancellation doesn’t automatically warrant custodial detention of the accused: there must be cogent reasons backed by material to justify such harsh action. This principle was reiterated in Mehboob Dawood Shaikh v. State of Maharashtra [(2004) 2 SCC 362] and Deepak Yadav v. State of U.P. [CRIMINAL APPEAL NO. 861 OF 2022 (arising out of S.L.P (Crl.) No. 9655 of 2021)], where the Hon’ble Supreme Court reiterated that courts must be careful while exercising power under Section 439(2) CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, as cancellation of bail is not only a harsh order but also an order of curtailment of personal liberty.

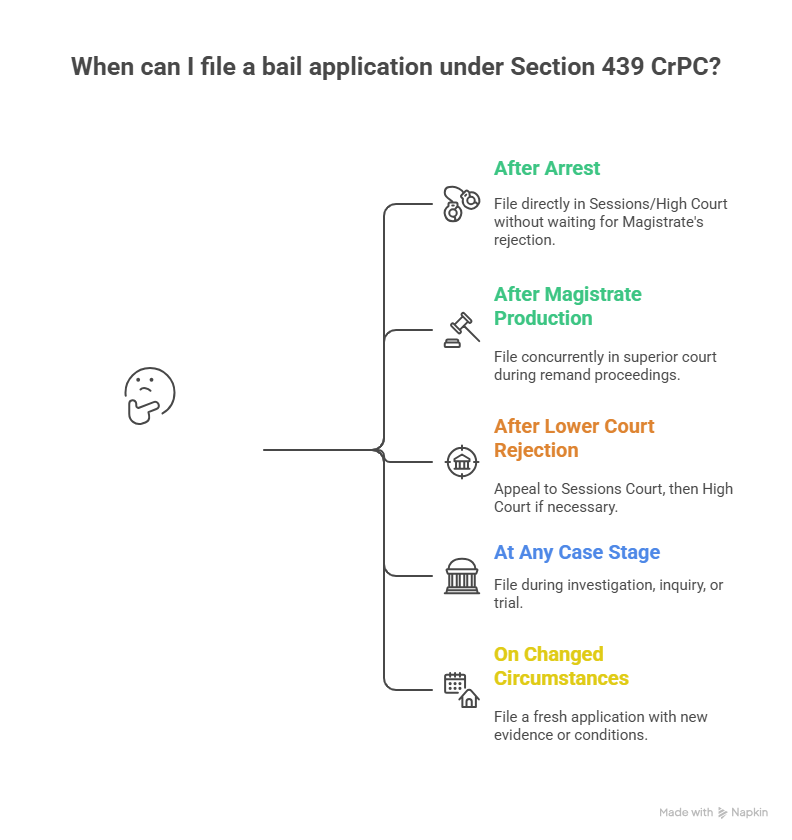

When Can You File An Application Under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS)?

Understanding the timing of when you can approach the High Court or Sessions Court under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS BNSS is crucial for protecting your liberty. Here are the key scenarios when this provision becomes available to you:

- After Arrest and Custody: Once you’ve been arrested by police and taken into custody, you can immediately file a bail application under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS in the Sessions Court or High Court. You don’t need to wait for the Magistrate to reject your bail first: the power under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS is concurrent and independent. In Sundeep Kumar Bafna (supra), the Supreme Court explicitly held that there’s no legal impediment to an accused approaching the Sessions Court or High Court directly for regular bail under Section 439 CrPC (now section 483 BNSS), even without first approaching the Magistrate.

- After Production Before Magistrate: When police produce you before the Magistrate for remand proceedings, and the Magistrate sends you to judicial custody or police custody, you can file a Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS application in the superior courts at this stage. The fact that remand proceedings are ongoing before the Magistrate doesn’t bar your right to approach Sessions Court or High Court for bail. This concurrent jurisdiction ensures you’re not stuck waiting for lower court proceedings while remaining in custody.

- After Rejection by Lower Court: The most common scenario for Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS applications is when a Magistrate has already rejected your bail application under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS. If your bail plea is dismissed by the Chief Judicial Magistrate or Judicial Magistrate First Class, you can immediately approach the Sessions Court with a fresh bail application with the said provisions. If the Sessions Court also rejects your application, you can then move to the High Court; this hierarchical progression is the typical path for bail applications in serious offences.

- At Any Stage During Investigation, Inquiry or Trial: Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS applications can be filed at any stage of the criminal proceedings – whether during police investigation before chargesheet filing, during inquiry proceedings, or even during trial after charges have been framed. In Aslam Babalal Desai v. State of Maharashtra AIR 1993 SC 1, the Supreme Court clarified that the power under Section 439 is not restricted to any particular stage and can be invoked whenever the accused is in custody, regardless of how far the case has progressed.

- On Changed Circumstances: Even if your previous bail application under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS was rejected by the Sessions Court or High Court, you can file a successive bail application if there are changed circumstances. Changed circumstances include: prolonged incarceration without trial completion, deterioration of health requiring medical attention unavailable in custody, completion of investigation and filing of chargesheet, acquittal of co-accused in similar circumstances, or Supreme Court precedents laying down more liberal bail standards in offences similar to yours. Courts recognize that justice requires flexibility to respond to evolving situations rather than mechanically treating initial rejection as final.

Which Courts Have Jurisdiction Under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS)?

Understanding which court to approach for your Section 439 CrPC/Section Section 483 BNSSbail application is critical for your application’s success. Both the Sessions Court and High Court have concurrent jurisdiction under this provision, but strategic considerations may influence your choice.

Which Court Should You Approach: Sessions Court or High Court?

Generally, you should first approach the Sessions Court for bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section Section 483 BNSS, especially when a Magistrate has rejected your application. The Sessions Court is the natural appellate forum for Magistrate’s orders and is more accessible in terms of court fees, geographical proximity, and hearing timelines. From a practical standpoint, approaching the Sessions Court first preserves your right to approach the High Court later if the Sessions Court rejects your application, whereas approaching the High Court directly means you’ve exhausted your higher forum options.

Can You Approach High Court Directly Without Going to Sessions Court?

Yes, you can approach the High Court directly for bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section Section 483 BNSS without first going to the Sessions Court or Magistrate. The power granted to both courts under Section 439 CrPC/Section Section 483 BNSS is concurrent, not hierarchical: meaning you have the option to choose which forum to approach based on your case circumstances. However, you should carefully weigh this decision because once the High Court rejects your bail application, you cannot then approach the Sessions Court with the same grounds, as the higher court’s decision binds the lower court.

Direct approach to the High Court makes strategic sense in certain situations: when your case involves significant legal questions requiring High Court’s attention; when the offence is extremely serious and you anticipate the Sessions Court may be reluctant to grant bail; when there’s urgent need for relief and the High Court’s vacation bench is sitting while Sessions Court is on holiday; or when there are conflicting judgments from different Sessions Courts on similar issues and you need the High Court’s clarification. The Supreme Court in Niranjan Singh v. Prabhakar Rajaram Kharote (1980) 2 SCC 559 held that the power under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) enables the High Court to entertain bail applications directly without requiring the accused to first approach lower courts, recognizing that personal liberty concerns may justify direct approach to the highest court in the state.

Can You File Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS Application in Both Courts Simultaneously?

No, you cannot file the aforesaid bail applications in both Sessions Court and High Court simultaneously. While both courts have concurrent jurisdiction, the principle of judicial propriety and hierarchy requires that you approach one forum at a time. Filing in both courts simultaneously amounts to forum shopping and is considered an abuse of the judicial process. Courts have consistently held that an accused must choose one forum and await that court’s decision before approaching another court.

However, if the Sessions Court rejects your application, you can immediately file a fresh application in the High Court. The High Court would then exercise its independent jurisdiction under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS rather than acting as an appellate court reviewing the Sessions Court’s order: though practically, the High Court will certainly consider the Sessions Court’s reasons for rejection while making its own independent assessment.

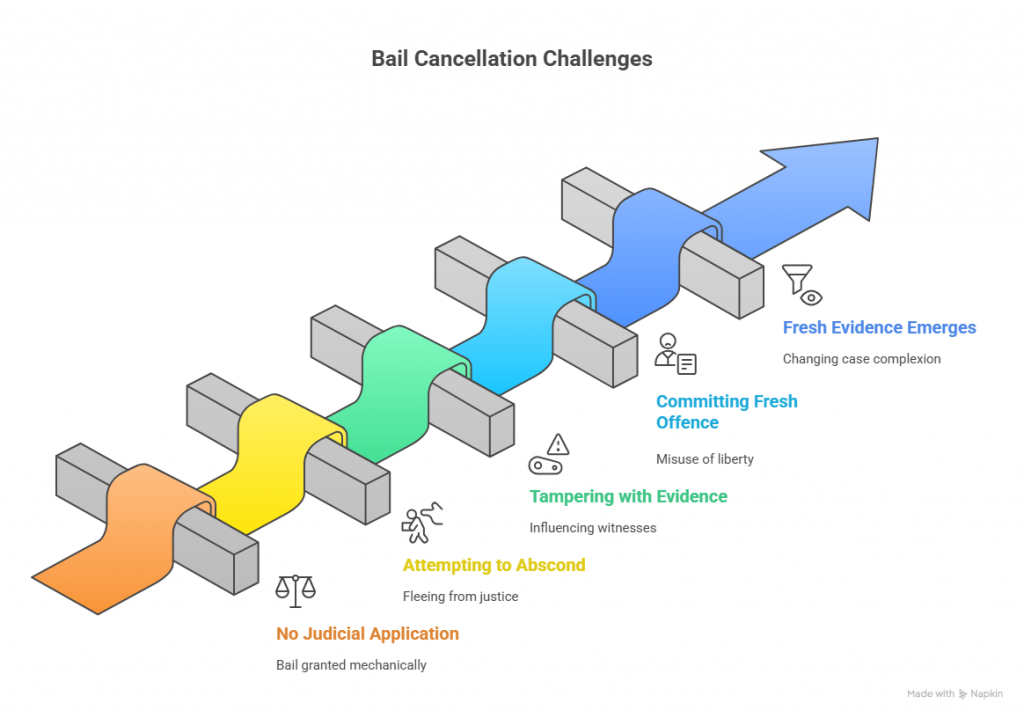

On What Grounds Can High Court or Sessions Court Cancel Bail?

Understanding when courts can cancel bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS is crucial because bail cancellation means immediate return to custody. Courts exercise this power carefully, recognizing that it curtails liberty previously granted after judicial consideration. Let me explain the main grounds for bail cancellation.

Bail Granted Without Judicial Application of Mind

Courts can cancel bail when the original bail order was passed mechanically without proper consideration of relevant factors or without recording reasons. If the judge who granted bail failed to examine the nature of allegations, strength of evidence, risk of absconding, or possibility of witness tampering, the order suffers from non-application of mind. This ground doesn’t mean the judge made a wrong decision, it means the judge didn’t properly evaluate the decision at all.

The Supreme Court in Ramesh Bhavan Rathod v. Vishanbhai Hirabhai Makwana [2021 SUPREME COURT 2011] emphasized that courts granting bail must record reasons, however brief, demonstrating judicial application of mind to the facts and circumstances. The Court held that a bail order without reasons is vulnerable to being set aside for lack of due application of judicial mind. When reviewing bail cancellation applications, superior courts examine whether the original bail order reflected consideration of standard bail factors or was merely a routine order passed without proper scrutiny.

Accused Attempting to Abscond or Evade Trial

If after getting bail you attempt to flee from justice, fail to appear for court hearings without valid reasons, or make preparations to leave the country despite restrictions, courts can cancel your bail immediately. Absconding defeats the fundamental premise of bail: that you’ll appear for trial when required. Even attempts to abscond without actually fleeing can justify cancellation, such as selling property in preparation for flight, applying for passport renewal when your passport was ordered to be surrendered, or being found at international borders attempting to cross without permission.

Tampering with Evidence or Influencing Witnesses

Bail cancellation is warranted when you use your liberty to interfere with the prosecution’s case by destroying evidence, creating false documents, threatening or bribing witnesses, or attempting to influence the victim or complainant. Courts view evidence tampering extremely seriously because it strikes at the heart of the justice system’s ability to determine truth. Even subtle pressure on witnesses, such as repeated visits to their homes or sending intermediaries to “request” them not to testify, can constitute grounds for bail cancellation if brought to the court’s notice with supporting evidence.

Committing Another Offence While on Bail

If you commit a fresh criminal offence while out on bail, particularly an offence of similar nature to the original charge, courts can cancel your bail in the original case. This demonstrates that you’ve misused the liberty granted to you and that releasing you poses danger to society. The fresh offence need not be as serious as the original charge; even committing a bailable offence while on bail for a non-bailable offence shows disregard for the law and can justify cancellation. Courts interpret such conduct as evidence that bail was improperly granted or that circumstances have changed materially since the grant of bail.

Fresh Evidence Emerging After Bail Grant

When new evidence surfaces after bail was granted that materially changes the complexion of the case or shows the offence is more serious than initially understood, courts can cancel bail. For instance, if bail was granted based on the understanding that the injury to the victim was simple, but later medical evidence reveals grievous injuries, this changed factual matrix justifies bail cancellation. Similarly, if initially it appeared the accused had no criminal history, but subsequent investigation reveals multiple prior offences, this fresh evidence supports cancellation.

What to Do When Your Application under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) Gets Rejected?

Facing a bail rejection is disheartening, but it doesn’t mean you’re out of legal options. Understanding your next steps is crucial for continuing your fight for liberty.

Filing an Appeal in High Court Against Session Court’s Bail Rejection Order

When the Sessions Court rejects your Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS bail application, you can immediately file a fresh bail application in the High Court under this very provision. This isn’t technically an “appeal” but rather an invocation of the High Court’s independent concurrent jurisdiction. The High Court will conduct a fresh examination of your bail plea rather than merely reviewing whether the Sessions Court’s order was correct. You can present the same grounds along with additional arguments, cite more case laws, or highlight changed circumstances since the Sessions Court’s rejection. The High Court isn’t bound by the Sessions Court’s view, though it will certainly consider the reasons given by the Sessions Court while forming its independent opinion.

Approaching the Supreme Court Against High Court’s Bail Rejection Order

If the High Court rejects your Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS bail application, your final remedy is filing a Special Leave Petition (SLP) under Article 136 of the Constitution before the Supreme Court of India. The Supreme Court doesn’t hear bail matters as appeals but as exceptional cases requiring its intervention in the interest of justice. You must demonstrate either that the High Court’s order suffers from manifest illegality, or that your continued detention amounts to violation of fundamental rights, or that there are compelling humanitarian grounds such as serious illness or extraordinarily long trial delays. The Supreme Court’s bail jurisdiction is discretionary and exercised sparingly, focusing on cases involving gross miscarriage of justice or arbitrary denial of liberty.

Bail under special circumstances vs Other Types of Bail

Understanding how Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS relates to other bail provisions helps you navigate the criminal justice system effectively and choose the right legal remedy for your situation.

Difference between Section 439 CrPC and Section 437 CrPC?

Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS and Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS both deal with bail in non-bailable offences, but they differ fundamentally in the courts that exercise these powers and the scope of discretion available.

Magistrate Powers Under Section 437 CrPC vs High Court/Sessions Court Powers Under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS

Under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, Magistrates have limited power to grant bail in non-bailable offences. A Magistrate cannot grant bail for offences punishable with death or life imprisonment, except in three specific situations: when the accused is under 16 years of age, when the accused is a woman, or when the accused is sick or infirm. This restriction reflects legislative caution about Magistrates granting bail in the most serious crimes. Additionally, even when granting bail in other non-bailable offences, Magistrates must be satisfied that there are reasonable grounds for believing that the accused is not guilty of the alleged offence, and that they’re not likely to commit further offences while on bail.

In contrast, Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS grants High Courts and Sessions Courts much wider powers without these statutory limitations. These superior courts can grant bail in ANY case, including offences punishable with death or life imprisonment, regardless of the accused’s age, gender, or health status. Under this provision, the discretion is broader and more flexible: while these courts still consider the same factors (gravity of offence, evidence strength, flight risk, etc.), they’re not bound by the categorical restrictions that limit Magistrates. This expanded power recognises that superior courts have greater institutional capacity and experience to balance individual liberty against societal interests in serious criminal cases.

Which Offences Can Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS Cover That Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS Cannot?

Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) covers several categories of offences where Magistrates under Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS) are powerless to grant bail. The most significant category is offences punishable with death penalty: cases such as murder, waging war against the Government of India, or dacoity with murder where Magistrates cannot grant bail to accused who don’t fall into the three exceptional categories mentioned earlier. For instance, if a healthy 30-year-old man is accused of murder, a Magistrate cannot grant him bail under Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS), but the Sessions Court or High Court can consider his bail application under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS).

Similarly, offences punishable with life imprisonment such as certain serious drug trafficking charges under the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985, organized crime under Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act 1999, or terrorist activities under Unlawful Activities Prevention Act 1967 (UAPA) fall outside the Magistrate’s bail jurisdiction in most cases. Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) also covers situations where Magistrates have already rejected bail under Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS), once the Magistrate says no, the accused cannot get bail from the Magistrate again on the same facts, but can approach Sessions Court or High Court under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS). This hierarchical structure ensures that denial of bail by one level of judiciary doesn’t permanently close all doors to liberty, recognizing that different courts may take different views on the same facts.

How is Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS different from Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS (Anticipatory Bail)?

The fundamental difference between Section 439 CrPC/ Section 483 BNSS and Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS lies in the timing of the application: one is for pre-arrest protection while the other is for post-arrest release.

Pre-Arrest Bail (Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS) vs Post-Custody Bail (Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS)

Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS allows you to seek anticipatory bail BEFORE arrest when you have reason to believe you may be arrested for a non-bailable offence. This pre-emptive protection is available when you anticipate arrest based on credible information: perhaps you’ve received a police notice, or you know an FIR is about to be filed against you, or you learn that a non-bailable warrant has been issued. Anticipatory bail applications can only be filed in Sessions Court or High Court, not before Magistrates. The core idea is to protect innocent persons from the humiliation and trauma of arrest when there’s likelihood of false implication in criminal cases, while ensuring they remain available for investigation.

Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, on the other hand, comes into play only AFTER you’re in custody: whether police custody or judicial custody. You must be physically arrested and deprived of liberty before Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS becomes applicable. The Supreme Court in Niranjan Singh (supra) clarified that “in custody” for Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS purposes means physical control by authorities, or physical presence in court coupled with submission to the court’s jurisdiction. Even if you surrender before court voluntarily, that counts as custody enabling you to seek bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, but until that point, Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS is your only pre-arrest remedy.

The standards for granting bail also differ subtly between the two provisions. For anticipatory bail under Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS, courts examine whether there’s genuine apprehension of arrest, whether the accusation appears to be false or motivated, and whether custodial interrogation is truly necessary. The court must balance your liberty interest against the State’s need to investigate effectively. For regular bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS after arrest, courts focus more on whether continued custody is justified given the stage of investigation/trial, your conduct while in custody, the likelihood of trial completion, and whether you pose a flight risk or threat to witnesses. The underlying question shifts from “should this person be arrested at all?” under Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS to “should this person continue in custody?” under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS.

Can You File Both Section 437 CrPC (Section 480 BNSS) and Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) Applications Simultaneously?

No, you cannot file bail applications under both Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS), (before Magistrate) and Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS (before Sessions Court or High Court) simultaneously. This would amount to approaching multiple forums for the same relief, which courts view as forum shopping and abuse of process. You must choose one forum and pursue your bail application there, waiting for that court’s decision before approaching another court. However, the powers under these sections are complementary, not mutually exclusive, in the sense that you can file under Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS) first, and if rejected, then file under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS; this sequential approach is perfectly valid and commonly followed.

Do Old Supreme Court Judgments on Section 439 CrPC Still Apply Under Section 483 BNSS?

Yes, Supreme Court judgments interpreting Section 439 CrPC continue to have full binding precedent value under Section 483 BNSS. The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, replaced the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973, with effect from July 1, 2024, but Section 483 BNSS is virtually identical to Section 439 CrPC in its language and legal effect. Since the substantive content and scheme of the provision remain unchanged, all judicial precedents developed over five decades under Section 439 CrPC continue to guide courts in interpreting and applying Section 483 BNSS. Landmark judgments on the meaning of “custody,” scope of concurrent jurisdiction, standards for granting or refusing bail, and grounds for bail cancellation remain authoritative law under the new code.

Important Supreme Court Judgments on Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS)

Understanding landmark Supreme Court judgments helps you frame effective bail applications and anticipate how courts approach Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS cases. These cases have shaped bail jurisprudence in India.

Sundeep Kumar Bafna vs State of Maharashtra [(2014) 16 SCC 623]- Direct Approach to Superior Courts

Facts of the Case

Sundeep Kumar Bafna was arrested in connection with criminal charges and sought bail under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) by directly approaching the Sessions Court without first filing a bail application before the Magistrate. The Sessions Court questioned whether it had jurisdiction to entertain the bail application since the accused hadn’t first approached the Magistrate under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS. The Sessions Court raised the preliminary issue of whether the hierarchical structure of courts required accused persons to first approach Magistrates before approaching Sessions Courts or High Courts for bail.

Key Issues Before the Court

The primary legal issue was whether an accused in custody must first approach the Magistrate for bail under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS and await rejection before approaching the Sessions Court or High Court under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, or whether Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS grants independent concurrent jurisdiction allowing direct approach to superior courts. The question had practical significance because requiring accused persons to first approach Magistrates would delay bail hearings and unnecessarily prolong custody, while allowing direct approach would give accused persons more options and potentially faster relief.

Decision of the Court

The Supreme Court decisively held that there’s no legal impediment to an accused approaching the Sessions Court or High Court directly under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS without first approaching the Magistrate. The Court explained that Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS confers concurrent and independent jurisdiction on Sessions Courts and High Courts; this isn’t appellate jurisdiction over Magistrates’ orders but original jurisdiction to grant bail in any case where the accused is in custody. The Court noted that the power under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS is a special power meant to protect personal liberty, and reading procedural restrictions into it that don’t exist in the statutory language would defeat this purpose. This judgment removed a significant procedural hurdle and established that accused persons have genuine choice of forum when seeking bail.

Dataram Singh vs State of Uttar Pradesh (2018) – Discretion Must Be Exercised Judicially

Facts of the Case:

Dataram Singh was accused of serious criminal offences and filed a bail application under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) in the High Court. The High Court granted him bail, but the conditions imposed were extremely stringent and practically impossible to comply with, including requirement to furnish bail bonds of ₹5 lakhs with two sureties of like amount, despite the accused belonging to economically weaker section. The accused filed a petition seeking modification of these onerous bail conditions, arguing that while the High Court exercised discretion to grant bail, the conditions imposed were so harsh that the grant of bail became illusory and meaningless.

Key Issues Before the Court:

The central issue was whether courts, while exercising discretionary power to grant bail under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS), must ensure that bail conditions are reasonable and within the accused’s capacity to fulfill, or whether courts have unfettered discretion to impose any conditions they deem fit. The Court also examined whether bail conditions can be so stringent that they effectively convert bail grant into bail denial, thereby defeating the very purpose of granting bail. The case raised important questions about the balance between protecting society through bail conditions and ensuring meaningful access to liberty through bail.

Decision of the Court:

The Supreme Court held that while 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) grants discretionary power to courts in granting bail, this discretion must be exercised judicially, humanely, and compassionately, not arbitrarily or capriciously. The Court emphasized that bail conditions should not be so stringent that they become impossible for the accused to satisfy, thereby making the grant of bail illusory. Conditions must be proportionate to the offence charged, necessary for ensuring the accused’s presence during trial, and realistically achievable given the accused’s economic and social circumstances. The Court directed that excessive bail bonds amount to denial of bail and violate the constitutional guarantee of equality and right to life under Article 21. This judgment established important guidelines for ensuring bail conditions serve their legitimate purpose without becoming instruments of disguised detention.

Himanshu Sharma vs. State of Madhya Pradesh Union of India [2024 (4) SCC 222]- When can a bail get cancelled

Facts of the Case:

Himanshu Sharma was granted bail by the Sessions Court in a case involving allegations of fraud and cheating. After being released on bail, credible information emerged that he was attempting to contact and threaten witnesses in the case, including visiting their homes and sending intermediaries to persuade them not to testify against him. Additionally, the investigating agency discovered that Sharma had sold off his properties and was making arrangements to leave India despite a condition in his bail order prohibiting him from leaving the country without court permission. The prosecution filed an application under Section 439(2) CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) seeking cancellation of his bail on grounds of witness intimidation and preparation to abscond.

Key Issues Before the Court:

The Supreme Court was called upon to examine what standard of proof is required for bail cancellation: whether mere allegations of misconduct while on bail suffice, or whether concrete evidence of such misconduct must be demonstrated. The Court also examined whether preparatory acts toward absconding or witness tampering (such as selling property, applying for travel documents, visiting witnesses’ homes) constitute sufficient grounds for cancellation even if the accused hasn’t actually fled or directly threatened witnesses yet. The case raised the important question of when courts should exercise the harsh power of bail cancellation under Section 439(2) CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS).

Decision of the Court:

The Supreme Court held that bail cancellation is a serious matter that curtails liberty previously granted after judicial consideration, and therefore requires cogent material demonstrating abuse of bail or supervening circumstances that materially alter the situation prevailing when bail was granted. The Court emphasized that bail shouldn’t be cancelled merely on vague allegations or suspicions: there must be credible evidence, such as statements from threatened witnesses, documentary proof of attempts to destroy evidence, or concrete steps taken toward absconding (like selling assets, booking international flights, applying for passport renewal against court orders). The Court clarified that preparatory acts toward misconduct can justify cancellation even before the actual misconduct occurs: courts need not wait for the accused to actually flee the country or successfully intimidate witnesses before acting. However, the evidence of such preparatory acts must be reliable and not based on mere conjecture or motivated allegations by complainants seeking tactical advantage.

Union of India v. Man Singh Verma (2025 INSC 292)- Court exercising powers under section 439 CrPC cannot grant compensation

Facts of the Case:

Man Singh Verma was arrested in connection with criminal charges and remained in judicial custody for approximately 18 months. He filed a bail application under Section 439(2) CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) before the High Court. The High Court, while granting him bail, observed that he had suffered prolonged incarceration and directed the State Government to pay him compensation of ₹5 lakhs for his illegal detention and mental trauma suffered during custody. The High Court reasoned that since the accused was ultimately found entitled to bail, his continued custody for 18 months amounted to illegal detention warranting compensation under Article 21 of the Constitution. The Union of India challenged this order arguing that courts cannot grant monetary compensation while exercising bail jurisdiction under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS).

Key Issues Before the Court:

The Supreme Court examined whether a court exercising its jurisdiction under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) to grant bail can simultaneously award monetary compensation to the accused for prolonged custody or alleged illegal detention. The specific question was whether the power to grant bail includes ancillary power to award damages, or whether such relief requires separate proceedings like a writ petition under Article 226 or Article 32 of the Constitution or a civil suit for damages. The case also raised the issue of separation between criminal proceedings and civil remedies for compensation.

Decision of the Court:

The Supreme Court held that a court exercising power under Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) to grant bail cannot award monetary compensation to the accused as part of the bail order. The Court explained that Section 439 CrPC (now Section 483 BNSS) is a provision in criminal procedure dealing specifically with grant or refusal of bail, modification of bail conditions, and cancellation of bail, it doesn’t confer jurisdiction to adjudicate claims for damages or award monetary compensation. If an accused believes he suffered illegal detention or violation of constitutional rights warranting compensation, he must file separate proceedings such as a writ petition for enforcement of fundamental rights or a civil suit for damages against the concerned authorities. The Court clarified that recognizing a separate remedy for compensation doesn’t mean bail jurisdiction and compensation jurisdiction can be mixed: they operate in distinct legal spheres with different evidence requirements, different parties involved, and different standards of proof. This judgment established an important jurisdictional boundary preventing courts from conflating bail proceedings with compensation claims.

Conclusion

Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS stands as a powerful safeguard for personal liberty in India’s criminal justice system, granting High Courts and Sessions Courts special powers to grant bail even in the most serious offences where Magistrates lack jurisdiction. This provision embodies the constitutional principle that bail is the rule and jail is the exception, ensuring that accused persons aren’t left without remedy when lower courts reject their bail applications. The concurrent jurisdiction it grants to both Sessions Courts and High Courts provides flexibility for accused persons to choose the most appropriate forum based on their case circumstances, urgency of relief, and nature of offences charged.

Understanding provisions under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, procedural requirements like mandatory notice to Public Prosecutor in serious offences, grounds for bail cancellation under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, and the distinction from other bail provisions under Sections 437 CrPC (Section 480 BNSS) and Section 438 CrPC (Section 482 BNSS) empowers you to navigate bail applications more effectively. Whether you’re an accused person fighting for your liberty, a lawyer advocating for your client’s release, or a law student studying criminal procedure, mastering Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS helps you appreciate how Indian courts balance individual freedom against society’s legitimate interest in ensuring effective investigation and trial. The landmark Supreme Court judgments interpreting this provision continue to guide courts in exercising this discretionary power judicially, humanely, and in accordance with constitutional values of liberty, dignity, and fair trial.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS and when can it be used?

Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS grants High Court and Sessions Court special powers to grant bail in any case where accused is in custody, even in offences punishable with death or life imprisonment, and can be invoked after arrest, after magistrate rejection, or at any stage of investigation/trial.

Can I directly approach the High Court for bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS without going to the Magistrate?

Yes, you can directly approach the High Court or Sessions Court under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS without first going to the Magistrate, as these courts have concurrent and independent jurisdiction to grant bail whenever an accused is in custody, as held in the case of Sundeep Kumar Bafna (supra).

What does “in custody” mean for Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS bail?

“In custody” means physical control by police or judicial authorities, including arrest by police, judicial remand, police custody, or voluntary surrender before court submitting to its jurisdiction: even without formal arrest, surrender makes you eligible for Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS bail.

Is notice to the Public Prosecutor mandatory in all Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS cases?

Notice to Public Prosecutor is mandatory only for offences triable exclusively by Sessions Court or punishable with life imprisonment (general proviso), and for sexual offences as prescribed where 15-day notice is required.

Can High Court or Sessions Court cancel bail granted under Section 439/Section 483 BNSS CrPC?

Yes, under Section 439/Section 483, High Court and Sessions Court can cancel bail if granted without judicial mind application, accused attempts absconding, tampers with evidence, commits fresh offence while on bail, or fresh evidence materially changes case nature.

What grounds can I mention in Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS bail application?

Mention grounds like false implication with contradictory evidence, no custodial interrogation needed, permanent resident with family ties, no criminal antecedents, sole breadwinner, medical conditions requiring treatment, prolonged custody without trial completion, and willingness to abide by any conditions court may impose.

Can I file a successive bail application under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS after rejection?

Yes, you can file successive bail applications under Section 439/Section 483 if there are changed circumstances like prolonged incarceration, investigation completion, chargesheet filing, deteriorating health, co-accused getting bail, or new Supreme Court precedents establishing more liberal bail standards in similar offences.

Do I need a lawyer to file a bail application under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS?

While you can legally file a bail application without a lawyer, it’s strongly recommended to engage a criminal lawyer who understands local court procedures, can draft an application citing relevant case laws, present effective oral arguments during hearing, and knows judicial officers’ specific preferences for successful bail grant.

What conditions can court impose while granting bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS?

Courts can impose conditions like surrendering passport, regular police station reporting, restrictions on leaving jurisdiction/country, furnishing bail bonds with sureties, no contact with witnesses/complainant, and any other conditions necessary to ensure trial attendance and prevent evidence tampering.

Can Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS be used for anticipatory bail?

No, Section 439/Section 483 applies only when the accused is already in custody after arrest; for pre-arrest protection use Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS which specifically deals with anticipatory bail when you apprehend arrest but haven’t been arrested yet.

What happens if I violate bail conditions granted under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS?

Violation of bail conditions can lead to bail cancellation under Section 439(2)/Section 483(3), immediate re-arrest and custody commitment, forfeiture of bail bonds and sureties, and difficulty in getting bail again as violation demonstrates you’re unfit for liberty and misuse bail concessions.

Do the High Court or the Session Court need to record reasons for granting/refusing bail?

Yes, courts must record reasons while granting or refusing bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, as held in Ramesh Bhavan Rathod (supra): reasons need not be elaborate but must demonstrate judicial application of mind to relevant factors; cryptic orders without any reasoning can be set aside.

Can You Challenge Excessive or Unreasonable Bail Conditions?

Yes, you can file an application under Section 439(1)(b) CrPC/Section 483(1)(b) BNSS before High Court or Sessions Court to modify or set aside excessive bail conditions imposed by lower court; conditions must be proportionate to offence and within your capacity to fulfill.

Can Magistrate Cancel Bail Granted Under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS?

No, Magistrate cannot cancel bail granted by High Court or Sessions Court. Only the court that granted bail or a higher court can cancel it.

Can I download a format for bail application under section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS for free?

Yes, you can download free bail application formats from Lawsikho’s comprehensive Bail Application Format PDF guide which provides separate templates for Sessions Court and High Court applications with complete grounds, undertakings, and verification clauses.

Related reading: Bail: https://lawsikho.com/blog/bail/; Bail meaning: https://lawsikho.com/blog/bail-meaning/ and Interim Bail Meaning https://lawsikho.com/blog/interim-bail-meaning/

Allow notifications

Allow notifications