Complete AOR 2026 guide: Advocate on Record definition, constitutional framework, eligibility criteria, 4-paper exam pattern, registration process, salary (₹5-50L+), roles & Supreme Court career path.

Table of Contents

Curious who really holds the power to file cases in India’s Supreme Court? Meet the Advocate on Record (AOR), the exclusive class of lawyers authorized to act, plead, and file matters before the apex court. This comprehensive guide explains who AORs are, how to become one, the exam process, their earnings, and why this elite designation remains the ultimate badge of prestige in Indian litigation.

If you’ve ever wondered who actually has the power to file cases in India’s Supreme Court, the answer might surprise you: not every lawyer can do it.

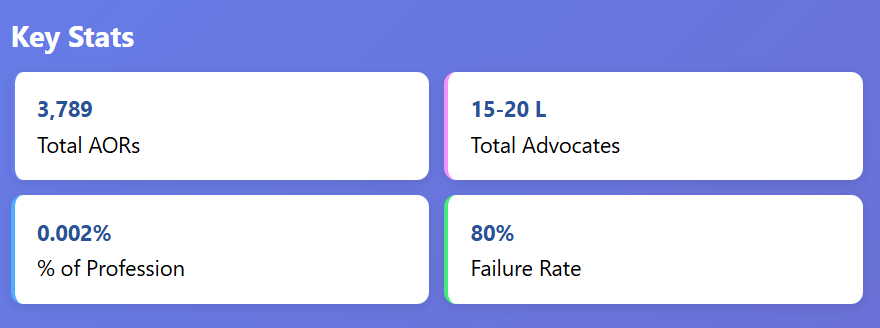

In fact, out of approximately 15 to 20 lakh practicing advocates across India, only 3,789 hold the exclusive designation that grants them this power. These select few are called Advocates on Record, or AORs, and they serve as the official gatekeepers to India’s highest court of law.

The AOR designation is more exclusive than many prestigious professional credentials in India. It represents less than 0.002% of the entire legal profession, a statistic that underscores just how elite and selective this category truly is. Yet despite this exclusivity, most Indians have never heard of Advocates on Record, and even many practicing lawyers don’t fully understand their critical role in India’s judicial system.

Whether you’re a law student exploring career paths, a practicing advocate considering a move to Supreme Court practice, or simply someone curious about how India’s legal system works, understanding the AOR designation is crucial.

This guide takes you through everything you need to know about the AOR system, from the legal definition and constitutional framework that governs it, to the eligibility criteria and examination process for becoming one, to the career opportunities and financial potential that this designation unlocks. Whether you’re considering pursuing the AOR designation yourself or simply want to understand what these legal professionals do, you’ll find comprehensive answers in the sections that follow.

What Does Advocate on Record Mean in India’s Legal System?

According to Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules 2013, an AOR is an advocate entitled to act as well as plead for a party in the Supreme Court of India. This means only AORs can file appearances, submit petitions, and handle all procedural work before the apex court. Even if you’ve practiced law for 30 years, you cannot independently file a single document in the Supreme Court without the AOR designation.

What sets AORs apart is that even Senior Advocates, the most distinguished lawyers in India cannot appear in the Supreme Court without an AOR instructing them. If you’re a successful High Court advocate whose client’s case reaches the Supreme Court, you’ll need an AOR to file it, even if you’re the one who’ll argue the matter. This unique role is what gives Advocates on Record their immense professional value and prestige.

Why AOR System is Critical for Supreme Court Functioning?

You might wonder why the Supreme Court needs this separate category of advocates at all. Why can’t any experienced lawyer file cases in the apex court? The answer lies in how the Supreme Court functions and the complexity of matters that reach India’s highest judicial forum. Let me explain why this system isn’t just bureaucratic red tape, it’s essential for the Court’s efficient operation.

The Supreme Court of India is the final court of appeal for all civil and criminal cases in the country. It also has original jurisdiction under Article 32 for protecting fundamental rights and under Article 131 for resolving interstate disputes. The Court hears thousands of cases every year involving complex constitutional questions, diverse legal issues from 25 High Courts across India, and documents often in vernacular languages from every corner of our nation.

Every matter before the Supreme Court involves voluminous records, intricate procedural requirements, and specialized filing formats unique to the apex court. Judges elevated to the Supreme Court from different High Courts may need assistance in understanding the apex court’s unique practice and procedure. This is where AORs become essential they serve as officers of the Court, bridging the gap between clients, advocates, and the bench itself with specialized procedural knowledge.

The AOR system ensures that only specially trained lawyers who have passed a rigorous examination handle Supreme Court filings. This maintains consistent standards of drafting quality, procedural compliance, and professional ethics. When an AOR signs a petition, the Court can rely on its accuracy and completeness without extensive scrutiny of every procedural detail. This trust factor is what allows the Supreme Court to process thousands of matters efficiently despite its heavy workload.

Key Statistics: Total Number of AORs in India

Let me share some eye opening numbers that highlight just how exclusive the AOR designation really is. These statistics will help you understand exactly what you’re aiming for if you’re considering this career path, and why clearing the AOR exam is considered one of the most significant achievements in Indian legal practice.

According to official Supreme Court records, there are exactly 3,789 Advocates on Record registered with the Supreme Court as of September 2025. Out of India’s 15-20 lakh practicing advocates, very few qualify as AORs making it more exclusive than many prestigious professional designations.

The numbers become even more striking when you look at the annual pass rate for the AOR examination. Approximately 80% of candidates fail the AOR exam in their first attempt. Out of roughly 1,000-1,200 people who appear for the examination each year, only about 200-240 successfully clear all four papers. In 2024 AOR exam 300+ cleared the AOR exam., This isn’t because the exam is designed to fail people, it’s because the knowledge and skills required for Supreme Court practice are genuinely demanding and specialized.

This exclusivity isn’t just about prestige, it directly impacts your career prospects and earning potential. Every single one of these 3,789 AORs are automatically a member of the Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA), the official body that represents their interests before the Court. Most AORs are based in Delhi and the National Capital Region, though successful practitioners from Mumbai, Kolkata, Chennai, Bangalore, and other cities have also earned this distinction while maintaining their local practice.

Legal Definition and Constitutional Framework

What is the Legal Definition of Advocate on Record?

Let me give you the precise legal definition that matters for understanding this designation and its significance in India’s judicial system. According to Order I of the Supreme Court Rules 2013, ‘advocate-on-record’ means an advocate who is entitled under these rules to act as well as to plead for a party in the Court. This definition might sound simple, but it carries enormous weight in practice and creates exclusive rights that no other advocate possesses.

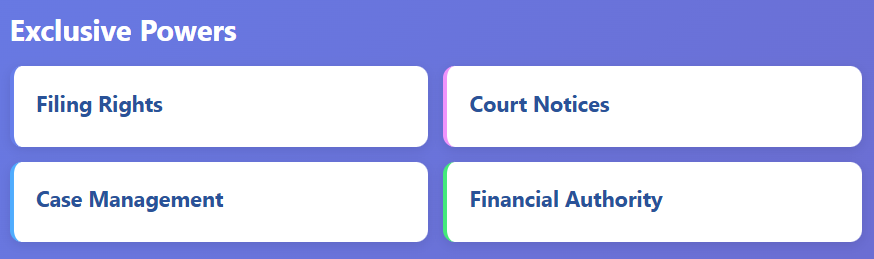

The key word here is “entitled.” Unlike regular advocates who may appear in the Supreme Court only with an AOR’s instructions, it is only an AOR who has the independent right to file cases, submit documents, and act on behalf of clients. Rule 1(b) of Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules 2013 states explicitly that no advocate other than an AOR shall be entitled to file an appearance or act for a party in the Court. This creates an absolute monopoly over filing rights that sets AORs apart from every other legal professional.

This means that every single petition, application, or document filed in the Supreme Court must bear an AOR’s signature and seal. Even if India’s most brilliant Senior Advocate drafts your petition or a specialized constitutional expert prepares your case, the actual filing can only be done by an Advocate on Record. The AOR’s name appears on the cause list, all court notices go to the AOR’s registered address, and the AOR bears personal responsibility for all procedural compliance.

The legal framework also makes AORs personally liable for all fees and charges payable to the Court. This isn’t just about filing documents, it’s about taking complete ownership of the case’s procedural journey through the Supreme Court system. When you become an AOR, you’re essentially registering yourself as a certified officer of the Supreme Court itself, not just as a private legal practitioner.

What is the Constitutional Framework Governing the AOR System?

Article 145 Constitutional Basis for AOR System

Article 145(1) of the Constitution grants the Supreme Court the power to make rules for regulating its practice and procedure, including rules about persons practicing before the Court. This constitutional provision is what empowers the Supreme Court to create specialized categories of advocates and set qualification standards for appearing before it.

What makes this provision powerful is that it’s “subject to the provisions of any law made by Parliament,” but Parliament has not enacted any law contradicting or limiting the AOR system.This means the Supreme Court has virtually complete authority to regulate its own practice standards without interference from either the executive or Parliament.

The Supreme Court has used this power strategically to create a three-tier system of legal professionals practicing before it: regular advocates (who can argue if instructed by AOR and with Court permission), Senior Advocates (designated for eminence but cannot file independently or do procedural work), and Advocates on Record (exclusive filing rights and procedural responsibilities). This hierarchy ensures the Court maintains control over quality and competence while allowing flexibility for oral advocacy talent.

Order IV of Supreme Court Rules 2013

The AOR designation is granted under Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules 2013. It is the comprehensive chapter that governs everything about the AOR system from eligibility criteria to duties to consequences of misconduct. If you’re serious about becoming an AOR, you need to be intimately familiar with every provision of this Order. Let me break down the key rules that will directly affect your journey and practice.

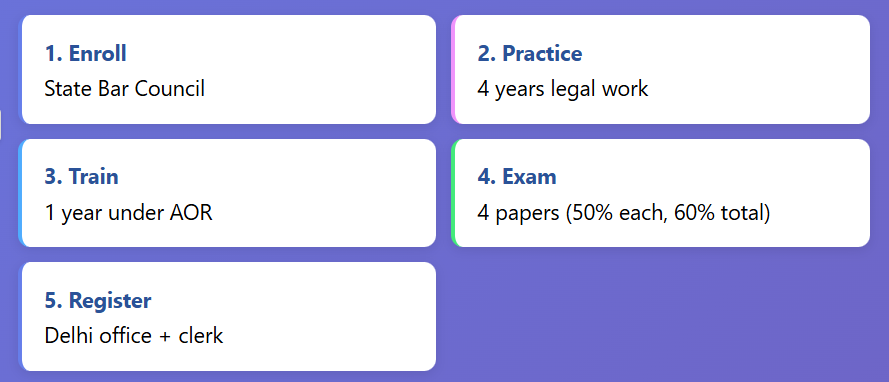

Rule 5 of Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 lays down the eligibility criteria for becoming an AOR. It specifies that an advocate must have completed at least four years of practice as an advocate before commencing the mandatory one year training under an existing AOR. This means you need a minimum of five years total from Bar Council enrollment that is four years of independent practice plus one year of specialized Supreme Court training under an AOR.

Rule 7 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 defines the scope of authority once you become an AOR. Once an AOR files a vakalatnama (power of attorney from client), they’re authorized to act, plead, conduct, and prosecute all proceedings related to that matter. They can deposit and receive money on behalf of the client, handle all correspondence with the Court, and take all procedural steps necessary for the case. This comprehensive authority comes with equally comprehensive responsibility.

Rules 10 of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 deals with AOR misconduct and consequences. These provisions prohibit name-lending (signing documents without actual involvement in the case), unauthorized absence from court when your cases are listed, and failure to submit proper appearance documentation. The Supreme Court takes these obligations seriously, and violations can result in suspension or removal from the AOR roll.

How AOR System Differs from Regular Advocates

Exclusive Rights and Privileges of AORs

Understanding what AORs can do that regular advocates cannot is crucial for appreciating why this designation is so valuable professionally and financially. Let me walk you through the exclusive privileges that come with the AOR title, these are rights that no other category of lawyer in India possesses at the Supreme Court level, making AORs absolutely indispensable for Supreme Court litigation.

First and most important, only an AOR can file a vakalatnama in the Supreme Court. The vakalatnama is the legal document appointing a lawyer to represent a client’s case in court. Without a valid vakalatnama filed by an AOR, no case can proceed in the Supreme Court. Even if you’re a party representing yourself per se, the procedural paperwork typically requires AOR involvement, though the Court does make exceptions for parties appearing in person in certain circumstances.

Second, every notice, order, and correspondence from the Supreme Court is sent exclusively to the AOR on record. This means the AOR is the official point of contact between the Court and the case. If the Court issues a notice, writ, summons, or other document, it goes to the AOR’s registered Delhi address or email address. Missing these communications can have serious consequences for your case, which is why clients depend completely on their AOR’s diligence in tracking case status and court directions.

Third, no person can act on behalf of an AOR except another AOR. If you’re an AOR who needs to travel or cannot attend to a matter, only another AOR can step in and handle the case on your behalf. Regular advocates, no matter how senior or experienced, cannot substitute for an AOR’s procedural functions. This creates a professional ecosystem where AORs often collaborate and cover for each other, but it also means clients must ensure their AOR has backup arrangements.

Fourth, AORs are personally liable for all court fees and charges payable in matters they handle. This means they have the authority to receive and deposit money on behalf of clients for Supreme Court matters, but they also bear personal responsibility if fees aren’t paid. This financial responsibility is why AORs typically maintain separate trust accounts for client funds and maintain meticulous accounting records as required under the Supreme Court Rules 2013.

Here’s something fascinating that many people don’t know: even law firms can be registered as AORs if all partners are individually AORs. This allows entire firms to operate with the AOR designation, which is a significant competitive advantage.

Comparison with High Court and District Court Practice

The AOR system is unique to the Supreme Court of India, no High Court or lower court in the country has a similar requirement. This distinction is important to understand because it affects how you plan your legal career, what additional qualifications you need for different levels of practice, and how you strategize your professional development as you gain experience.

In High Courts, any advocate enrolled with the State Bar Council can file cases, appear, and practice independently. You don’t need any special examination or designation beyond your basic Bar Council enrollment.

District Courts and trial courts are even more open in terms of access. Any enrolled advocate can appear and practice from day one after Bar Council enrollment. The barriers to entry are minimal once you have your Bar Council enrollment. You can build your practice based purely on your skills, networking, client development abilities, and litigation competence without any mandatory examinations.

But the Supreme Court sets a dramatically higher bar. You could be a 20 year veteran of High Court practice, you could have argued thousands of cases successfully, you could have a thriving practice with major clients, but you still cannot independently file a single document in the Supreme Court without the AOR designation. This creates a necessary collaboration ecosystem where experienced advocates work with AORs to bring their cases to the apex court.

This system means that if you’re a successful High Court advocate whose client’s case reaches the Supreme Court, you have essentially three options: find an AOR to file the case and give you instructions to argue it, become an AOR yourself if you meet the eligibility criteria, or refer the client to a Supreme Court practitioner who will handle both filing and arguments. Many advocates choose the first option, which is why there’s a thriving professional ecosystem of AORs who primarily handle filing and procedural work while other advocates handle the actual oral arguments.

Eligibility Criteria and Qualifications Required

Who Can Become an Advocate on Record?

Let me be completely straight with you about who can actually pursue this designation and what prerequisites you must satisfy. The Supreme Court has set clear eligibility criteria that you must meet before you can even think about starting the AOR journey. These requirements exist to ensure that only experienced, competent advocates with proven track records practice before India’s highest court.

First, you must be enrolled as an advocate with any State Bar Council in India under the Advocates Act 1961. This is non-negotiable,you need a valid Bar Council enrollment and your name must appear on the State roll with active status. Whether you’re enrolled in Delhi, Maharashtra, Kerala, or any other state doesn’t matter, any State Bar Council enrollment qualifies equally for AOR purposes.

Second, you cannot already be designated as a Senior Advocate by the Supreme Court or any High Court. This might seem counterintuitive, but Senior Advocates are explicitly ineligible to become AORs. The logic is that Senior Advocates focus exclusively on arguments and are prohibited from handling procedural work like drafting, filing, and case management under the designation rules. If you’re already a Senior Advocate, you work with AORs rather than becoming one yourself, this maintains the specialized division of labor the system is designed to create.

Third, you must have completed at least four years of actual legal practice as an advocate on the date you commence your one-year training under an AOR. This means effectively five years total from Bar Council enrollment to examination eligibility: four years of independent practice, then one year of specialized training. The Supreme Court is strict about this timeline, your practice experience must be genuine and verifiable, not just time elapsed since enrollment.

Fourth, you need to complete one year of continuous training under an Advocate on Record who is approved by the Supreme Court to impart training. Not every AOR can train aspiring advocates – they need specific approval and typically must have at least 10 years of AOR practice themselves. Finding the right training AOR is often one of the biggest practical challenges for aspirants based outside Delhi.

Minimum Experience Requirements: 4 Year Practice Rule

The four-year practice requirement is more nuanced than it appears on the surface, and understanding exactly what counts as “practice” can determine whether you’re eligible to start your AOR journey or need to wait longer. Let me clarify what the Supreme Court means by this crucial requirement and how it’s calculated in practice.

When the rules say four years of practice, they mean four years from the date of your enrollment with a State Bar Council, not from your law degree completion date. If you completed your LLB in 2018 but enrolled with the Bar Council only in 2020, your practice period starts counting from 2020. This is a common mistake aspirants make when calculating their eligibility timeline, always count from Bar Council enrollment date, not degree date.

The practice must be as an advocate, meaning active legal work involving court appearances, legal consultancy, drafting, or other professional legal services. During your training and examination, your practical knowledge and skills become evident, which is why genuine practice experience matters.

The four years need to be completed before you start your one-year training under an AOR, not before you appear for the exam. This means if you completed four years of practice in January 2024, you can immediately start training under an AOR in February 2024, complete training by February 2025, and appear for the next available AOR examination after that typically in May-June 2025. This timing allows you to move continuously through the qualification process.

There’s no upper age limit or maximum experience requirement for becoming an AOR. Whether you have 5 years of practice or 25 years, you’re eligible as long as you meet the minimum four-year threshold and other criteria. Many successful AORs began their journey mid-career, bringing valuable litigation experience to their Supreme Court practice. I’ve seen advocates in their 40s and 50s successfully clear the exam and establish thriving Supreme Court practices, often bringing their existing client relationships into their new AOR practice.

Exemptions from Mandatory Training or Writing the AOR Examination

While most advocates must follow the standard route of training and examination, the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 does provide specific exemption that you should know about.

The undermentioned categories of advocates are exempted from training and appearing for the AOR Examination as per Order IV Rule 5 of the Supreme Court Rules:

- an attorney;

- a solicitor on the rolls of the Bombay Incorporated Law Society if his/her name is, and has been borne on the roll of the State Bar Council for a period of not less than seven years on the date of making the application for registration as an advocate-on-record

The Chief Justice of India may also grant an exemption:

- from the requirement of the mandatory training in the case of an advocate, whose name is borne on the roll of any State Bar Council for a period of not less than ten years.

- from the requirement of four years of practice and from mandatory training in the case of an advocate having special knowledge or experience in law.

What are the Disqualifications for the AOR Examination

Understanding what can disqualify you from appearing for the AOR examination is just as important as knowing the eligibility criteria. The Supreme Court maintains strict standards for professional conduct and integrity, and certain circumstances can prevent you from pursuing AOR designation even if you otherwise meet the basic eligibility requirements.

Order IV Rule 6 of the Supreme Court Rules 2013 states that if an advocate is convicted of a crime involving “moral turpitude” (think fraud, bribery, forgery, etc), that advocate cannot take the Advocate-on-Record (AOR) exam unless the conviction has been stayed or suspended by any court or on and from the date of such conviction and thereafter for a period of two years with effect from the date he has served out the sentence, or has paid the fine imposed on him.

Provided that the Chief Justice may, if he thinks fit so to do, relax the provisions of this rule in any particular case or cases

This does not apply to an advocate who has been released on probation of good conduct or after due admonition and no penalty has been imposed thereafter in the manner provided under the provisions of the Probation of Offenders Act, 1958 (20 of 1958) or under section 360 of the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (2 of 1974).

Step-by-Step Procedure to Become AOR

Phase 1: Pre-examination

Mandatory One-Year Training Under Senior AOR

The one-year training period under a senior AOR is not just a formality or box-ticking exercise, it’s an intensive learning phase that prepares you for both the examination and actual Supreme Court practice. Let me walk you through what this training actually involves, why it’s structured this way, and what you should focus on during this crucial year.

Your training must be under an Advocate on Record who has been specifically approved by the Supreme Court to impart training. Typically, these are senior AORs with at least 10 years of Supreme Court practice experience who understand Supreme Court procedures thoroughly and have demonstrated capability to effectively mentor aspiring advocates.

Your training AOR is professionally and personally responsible for certifying that you have completed one full year of genuine training and are ready to appear for the examination. This certificate is a mandatory document for your examination application and carries significant weight. The training AOR’s reputation and standing before the Supreme Court is on the line when they certify you, so serious training AORs take this responsibility very seriously and genuinely assess your preparedness before issuing the certificate.

Training Certificate and Documentation Process

To initiate your training under an AOR, the AOR Examination Cell requires submission of the following:

- A continuity certificate from the State Bar Council (original document)

- An enrollment certificate from the State Bar Council (self-attested photocopy)

- A practice certificate from the State Bar Council (self-attested photocopy), this is not applicable if you are a pre-AIBE candidate

- A letter from you on your official letterhead confirming commencement of training with the AOR Exam Cell

- A commencement certificate from your senior AOR, confirming that your training has begun

These documents must be submitted to the AOR Exam Cell within seven days of receiving the commencement certificate. You are not required to personally deliver the documents to Delhi, you can ask an authorized representative to submit them on your behalf. But ensure that your representative obtains copies of all documents and requests a receipt from the officer handling the submission.

After the document verification, the relevant department will send you an email notification. If any of the documents contain errors or is incomplete, you may resubmit corrected versions.

After completing one full year of continuous training, your training AOR must issue you a certificate on their professional letterhead stating that you have undergone training under their direct supervision for the required period. The certificate should specify the exact dates of training commencement and completion, confirming that the training lasted for a minimum of one year and that you participated actively and satisfactorily throughout this period.

You can find the sample templates here: AOR Training Intimation Documents.

Finding a Senior AOR for Training

Finding the right senior AOR for training is often the single most challenging step for aspiring advocates, especially those practicing outside Delhi. Let me share practical strategies for connecting with potential training AORs and convincing them to take you on as a trainee, based on what has worked for successful AOR candidates.

If you’re based in Delhi or NCR, you have the significant advantage of geographic proximity to the Supreme Court. You can visit the Supreme Court campus regularly, attend proceedings in courtrooms, and approach AORs practicing there after observing them in action. Many AORs have chambers in the Supreme Court complex or nearby areas like Tilak Marg, and you can make direct approaches after researching which AORs practice in your areas of interest, whether civil, criminal, constitutional, tax, service matters, or specific subject specializations.

For advocates based outside Delhi, the challenge is considerably greater but not insurmountable. Many senior AORs accept outstation trainees, especially now with virtual Supreme Court proceedings becoming normalized. You can reach out to AORs through their published contact information on the Supreme Court website explaining your background, practice experience, and genuine interest in Supreme Court practice. Personal references from senior advocates in your city who know Supreme Court practitioners can be invaluable in making these connections.

The Supreme Court Advocates-on-Record Association (SCAORA) can potentially be a resource for finding approved training AORs. While they don’t provide formal trainee-matching services, approaching SCAORA and explaining your situation may yield references or suggestions. Some AORs advertise their willingness to take trainees on legal forums, professional social media platforms like LinkedIn, or through communications with bar associations in different cities seeking trainees from diverse backgrounds.

Be prepared to demonstrate serious commitment and professional competence when approaching potential training AORs. They’re investing significant time and effort in mentoring you, and they want assurance that you’re genuinely interested in Supreme Court practice, not just collecting a training certificate for credential purposes. Having a clear idea of what areas of law interest you, showing familiarity with recent Supreme Court judgments, demonstrating research skills, and expressing willingness to contribute meaningfully to their practice all help convince AORs to accept you as a trainee.

What Happens During the Training Period?

The training period is your deep dive into Supreme Court practice, and what you learn during this year directly impacts both your examination performance and your future success as an AOR. Let me describe what a typical training experience looks like and what you should focus on to maximize the value of this crucial year.

Your days during training typically involve attending Supreme Court proceedings regularly, either physically in courtrooms or virtually through video conferencing. You observe how AORs and Senior Advocates present arguments, how different benches ask questions and probe weaknesses in cases, and how legal issues are framed and debated at the highest judicial level. This observation teaches you the tone, style, argumentative techniques, and substantive depth expected in Supreme Court advocacy, which differs markedly from High Court or trial court practice.

You spend significant time assisting with petition drafting, which is where the real learning happens. Your training AOR will assign you drafting tasks – initially, you might compile lists of dates and events, gradually progressing to drafting complete petitions under close supervision. You learn the specific formats required by the Supreme Court Registry for different types of petitions, the art of writing concise yet comprehensive legal arguments that respect page limits, and the critical importance of proper annexures, pagination, and documentation.

You become intimately familiar with Supreme Court Rules through daily application. Your training AOR explains how these rules apply in real-world situations, shares insights from years of practice about how different Registry officials interpret rules, and teaches you troubleshooting techniques for common procedural challenges.

You learn the filing process at the Supreme Court Registry by accompanying your training AOR or their staff for actual filings. This includes understanding exactly what documents are needed for different types of petitions (SLPs, writs, original suits, transfer petitions), how to prepare index pages and annexure bundles properly, what defects commonly lead to Registry rejections and how to avoid them, and how to cure defects when the Registry issues defect memos. This hands on filing exposure is invaluable because textbook knowledge alone doesn’t prepare you for Registry practice realities.

Phase 2: AOR Examination Process

Application Procedure and Important Dates

The AOR examination is conducted annually by the Supreme Court of India, typically scheduled between May and June each year. Understanding the application timeline and process is crucial because missing deadlines or making errors in your application can cost you a year’s wait for the next examination cycle, which can significantly delay your AOR career plans.

The Supreme Court issues an official notification for the AOR examination several months in advance, usually around March or April. This notification is published on the Supreme Court website and is also circulated to all State Bar Councils across India. Here’s a sample notification for the June 2025 exam for your convenience. The notification specifies examination dates, application deadline, required documents, examination fee amount and payment mode, and the detailed syllabus for all four papers including any updates or changes from previous years.

Your application process begins with downloading the official application form from the Supreme Court website. The form requires extensive detailed information including your personal details (name, father’s name, date of birth, contact details), Bar Council enrollment information (which state, enrollment number, enrollment date), training completion particulars (training AOR’s name and registration number, training period dates). You must fill this form with meticulous care, ensuring all information matches your supporting documents exactly to avoid defect memos.

You need to submit the completed application form along with all supporting documents and your photograph to the Supreme Court Registry within the specified deadline mentioned in the notification. Some deficiencies in the application may be rectifiable within a specified period if permitted by the Registry. Therefore, it’s advisable to maintain regular follow-up on your application status through the Supreme Court’s online portal or by contacting the Registry directly.

After your application is accepted and all defects (if any) are cured, you receive an admit card approximately 2-3 weeks before the examination. The admit card specifies your examination center (usually in Delhi/NCR), reporting time for each paper, examination schedule with dates and timings, and instructions regarding permitted materials. You must bring your admit card, valid photo ID proof, and any other specified documents to each examination.

Required Documents and Submission Guidelines

The documentation required for your AOR examination application is extensive and demanding, and the Supreme Court Registry is notoriously strict about completeness and accuracy. Let me give you a comprehensive checklist of what you need to prepare and how to organize your submission to avoid rejection or defect memos.

Your completed application form is the foundation document. This must be filled carefully. Every field must be completed accurately with no corrections, overwriting, or use of correction fluid. Any fields that don’t apply to you should be marked as “Not Applicable” or “N/A” rather than left blank, as blank fields may be considered incomplete by the Registry.

Your Bar Council enrollment certificate is mandatory, and it must be self-attested. The certificate must clearly show your enrollment number, exact date of enrollment, and confirm that your name is currently on the State roll without any suspension, removal, or disciplinary restrictions.

The training completion certificate from your training AOR must be on the AOR’s professional letterhead with full address and contact details. It must be personally signed by the training AOR with their official seal and AOR registration number clearly mentioned. The certificate must explicitly state that you completed one full year of continuous training under their supervision, specifying the exact start and end dates of the training period. Vague or generic certificates without specific dates may be rejected.

Examination Fee Structure and Payment Modes

The examination fee for the AOR exam is relatively modest considering the prestigious designation and career opportunities you’re pursuing, but understanding the fee structure and payment process helps you complete your application smoothly without payment-related delays or complications.

As per recent examination notifications, the examination fee is ₹750. The precise fee amount is always specified in the official examination notification published on the Supreme Court website. Here’s a sample notification for the June 2025 exam for your convenience. This fee is strictly non-refundable, meaning if you pay and then decide not to appear for the exam, or if you appear but don’t clear it, or if your application is rejected for any reason, the fee amount is not returned under any circumstances.

Payment modes accepted by the Supreme Court have evolved with digital payment adoption. The fee payment must be made through online bank transfer to the account details provided in the exam notification. The system generates a payment receipt immediately upon successful transaction completion, which you must download, save, and print to attach with your physical application if required, or upload if applying online.

After making payment through any mode, you must retain the payment proof carefully and keep multiple copies. The payment transaction reference number or demand draft number needs to be accurately mentioned in your application form in the designated field. The Supreme Court Registry verifies payment status before processing your application, and any discrepancy in payment details, mismatch between paid amount and required fee, or inability to trace your payment can lead to application rejection even if all other documents are in order.

Phase 3: Post Examination Requirements

Registration Process with Supreme Court

Clearing the AOR examination is a tremendous achievement that very few candidates accomplish, but it’s not the end of your journey, you still need to complete the registration process with the Supreme Court to actually practice as an AOR. Let me walk you through this crucial final phase that many successful examinees find surprisingly complex and demanding.

Once examination results are declared (typically 2-3 months after the exam, usually in August or September), you need to submit a formal application for registration as an Advocate on Record to the Supreme Court Registry. This registration application is completely separate from your examination application and requires a fresh set of documents along with your exam pass certificate. Don’t assume that since the Registry has your examination documents, you don’t need to resubmit everything, the registration process starts fresh.

The registration application form can be obtained from the Registry office. You need to fill this form with your complete personal details, Bar Council enrollment information, training completion certificate, and most importantly, your proposed office address in Delhi within the 16 kilometers radius and details of the clerk you’ll employ or have already employed. These two requirements – Delhi office and registered clerk, often catch successful examinees off-guard if they haven’t planned ahead.

Along with the application, you must submit your original examination pass certificate issued by the Supreme Court (the Registry verifies it and returns it after marking it as “used for AOR registration”), updated Bar Council enrollment certificate confirming you’re still on the roll as of registration date with no interim disciplinary issues, current identity and address proofs, recent photographs, comprehensive proof of your office in Delhi within the specified radius from Supreme Court, proof of clerk employment or undertaking to employ clerk within one month, and the modest registration fee currently set at ₹250 paid through demand draft or as specified in the registration form.

The Supreme Court Registry scrutinizes registration applications carefully, and this stage can involve back-and-forth communication if your office proof is inadequate or clerk documentation is incomplete. The Registry wants clear evidence that you have a genuine, accessible office in Delhi, not just a mail-forwarding address or virtual office. Similarly, clerk registration requires that your clerk meets certain eligibility criteria and is registered with the Supreme Court as a clerk, which involves a separate process I’ll explain in the next section.

Office Setup Requirements in Delhi

The office requirement is one of the most practical and challenging aspects of becoming an AOR, especially for advocates based outside Delhi who want to maintain their existing practice while adding Supreme Court work. The Supreme Court Rules specify that an AOR must maintain an office within a radius of 16 kilometers from the Supreme Court building. This isn’t optional or flexible, it’s a mandatory requirement that the Registry enforces strictly.

Your office can be either owned or rented, but you need proper documentation proving it. If you own the office space, you need to provide property ownership documents like sale deed, property tax receipts, electricity connection in your name, and municipal records showing the property address. If you’re renting office space (which is more common for new AORs), you need a registered rent agreement or leave and license agreement, a No Objection Certificate from the property owner permitting you to use the premises as an AOR office, recent rent receipts proving you’re actually paying rent and occupying the space, and utility bills (electricity, water) showing the office address.

The office must be a genuine, accessible space where clients can meet you and court officials can verify your presence if needed. Residential addresses are generally not accepted as AOR office addresses unless you can demonstrate that you operate a professional legal practice from a dedicated part of the residence with separate entry and professional setup. Mail-forwarding services, virtual office addresses, or shared co-working spaces without dedicated desk allotment typically don’t satisfy the Registry’s requirements for office proof.

Many new AORs, especially those from outside Delhi, share chamber space with established AORs or senior advocates to meet this requirement cost-effectively. Chamber-sharing arrangements are completely legitimate and widely practiced, you can share physical space with other AORs and split the rent, as long as you have a formal sub-letting agreement and the primary leaseholder provides NOC for your use of the space. Some established AORs offer chamber-sharing specifically for newly registered AORs, which also provides mentorship opportunities and practice development benefits beyond just satisfying the office requirement.

The 16-kilometer radius from the Supreme Court building covers most of central Delhi, parts of South Delhi, and some NCR areas close to Delhi border. The Registry has specific guidelines for calculating this radius, and you should verify your proposed office location’s distance from the Supreme Court before finalizing any rental agreement. Getting an office slightly beyond the permitted radius and then having your registration application rejected due to this technical violation would be a costly mistake.

Clerk Registration and Employment Obligations

The requirement to employ a registered clerk is unique to the AOR system and serves important functions in Supreme Court practice, though many aspiring AORs underestimate the complexity of satisfying this requirement properly. Let me explain what this requirement involves, how to register a clerk, and your ongoing obligations regarding clerk employment.

A registered clerk is essentially your authorized assistant for handling procedural matters at the Supreme Court Registry. The clerk can file documents on your behalf, collect certified copies, track case status, attend to routine Registry work, and handle the physical logistics that Supreme Court practice involves. Every AOR must employ at least one registered clerk, and the clerk’s name is officially recorded with your AOR registration, making this a formal professional relationship regulated by Supreme Court Rules.

To register a clerk, the person must meet basic eligibility criteria: they should be at least 18 years old, should have minimum educational qualifications (typically at least 10th or 12th pass), and should not have any criminal record or disqualifications. The clerk registration process involves submitting an application to the Supreme Court Registry with the clerk’s personal details, educational certificates, identity proof, your (the AOR’s) details and registration number.

This clerk identity card allows them access to the Registry for filing and other official work on your behalf.

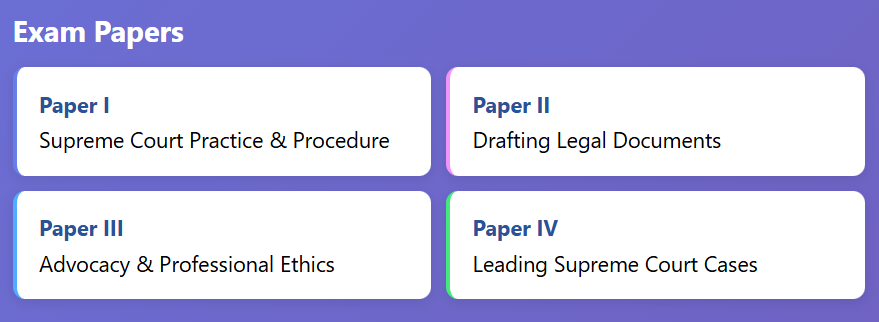

What is the AOR Exam Pattern and Structure?

Four Papers Overview: Marks and Duration

The AOR examination is a comprehensive assessment designed to test your readiness for Supreme Court practice across multiple dimensions namely procedure, drafting, ethics, and leading cases. Understanding the exam structure helps you prepare strategically and allocate your preparation time effectively across different papers based on their weightage and your strengths.

The examination consists of four papers, each carrying 100 marks, for a total of 400 marks. Each paper is typically three hours in duration with drafting paper having 30 minutes extra for reading, and the papers are usually conducted over a span of 4 days. All papers are written examinations (not objective/multiple choice), requiring detailed written answers, legal analysis, drafting exercises, or case commentaries depending on the paper’s nature.

Paper I covers Supreme Court Practice and Procedure, testing your knowledge of Supreme Court Rules, 2013, filing procedures, jurisdiction, and procedural law specific to apex court practice. This paper forms the backbone of the examination because procedural knowledge is absolutely essential for AOR practice, and it typically contains both theoretical questions about rules and practical scenarios requiring you to apply procedural rules to hypothetical situations.

Paper II focuses on Drafting, requiring you to draft various legal documents commonly used in Supreme Court practice. You might be asked to draft a Special Leave Petition, a writ petition, an application for stay, a written submission, or other documents. This paper tests not just your legal drafting skills but also your understanding of Supreme Court-specific formats, conciseness requirements, and persuasive legal writing techniques.

Paper III covers Advocacy Professional Ethics, examining your understanding of professional conduct rules for advocates, ethical dilemmas in legal practice, duties to clients and courts, and principles of professional responsibility. This paper also tests your knowledge of advocacy techniques, court conduct, and the specific ethical standards expected of AORs as officers of the Supreme Court.

Paper IV tests your knowledge of Leading Cases covering landmark Supreme Court judgments across various areas of law including constitutional law, civil law, criminal law, and other significant areas. You need to know not just the facts and holdings of important cases, but their reasoning, legal principles established, subsequent application, and continuing relevance. This paper requires extensive case law study and the ability to analyze and apply precedents.

Passing Criteria and Marking Scheme

Understanding the passing criteria is crucial because the AOR examination has a unique two-tier passing standard that’s more demanding than most legal examinations. You can’t compensate for weakness in one paper with strength in another, you need to perform adequately across all four papers to qualify as an AOR.

The passing criteria require you to secure at least 50% marks in each individual paper AND an aggregate of at least 60% marks across all four papers combined. This means scoring 50 marks out of 100 in each paper individually, plus achieving 240 marks out of 400 total. This dual requirement ensures that AORs have balanced competence across all areas rather than being strong in one or two areas while weak in others.

Let me give you an example to clarify: suppose you score 70, 65, 75 in the first three papers but only 40 in the fourth paper. Even though your total is 250 out of 400 (which is 62.5% and exceeds the 60% aggregate requirement), you’ve still failed the examination because you scored below 50% in one paper. Both conditions must be satisfied simultaneously with minimum 50% in each paper individually plus minimum 60% overall aggregate.

The marking scheme within each paper varies depending on the question type and examiner’s approach, but generally, examiners look for accuracy of legal knowledge, clarity of expression, relevance of answers to questions asked, practical understanding rather than just theoretical knowledge, and proper citation of rules, cases, or authorities where relevant. In drafting papers, format compliance, conciseness, legal soundness, and persuasiveness all affect your marks.

The examination results typically include your marks in each paper separately and your total aggregate marks. Your rank in the examination is also published being a rank holder (especially in top 10-20 ranks) adds prestige when you begin practice and can be a marketing point when establishing your AOR practice and attracting clients.

Exam Mode and Conduct Guidelines

The AOR examination is conducted as a written examination with physical attendance at designated examination centers, though there have been occasional discussions about online examination modes in exceptional circumstances. Understanding the examination conduct rules helps you prepare properly and avoid any conduct violations that could lead to disqualification.

The examination is typically held at centers in Delhi/NCR given the small number of candidates and the centralized nature of AOR practice. You need to report to your designated examination center (specified in your admit card) at least 30 minutes before the scheduled examination start time for each paper. Late arrivals beyond 15-30 minutes after the scheduled start time are typically not permitted entry to the examination hall.

You must bring your admit card and valid photo identification (Aadhaar card, PAN card, passport, or voter ID) to each examination session. Without these documents, you will not be allowed to enter the examination hall. You should also bring your own pens (typically blue or black ink), though answer booklets are provided by the examination center. Electronic devices including mobile phones, calculators, smartwatches, or any communication devices are strictly prohibited in the examination hall.

The examination is closed-book, meaning you cannot refer to any books, notes, or study materials during the examination. You must answer from memory and your understanding of the subjects. However, for the drafting paper, some examination cycles may allow reference to bare acts or Supreme Court Rules, while others may not – the examination notification specifies whether any reference materials are permitted, so check carefully and don’t assume what will or won’t be allowed.

Examination conduct rules prohibit any form of unfair means including copying from others, use of written notes or electronic devices, communication with other candidates, or any behavior that compromises examination integrity. Violation of conduct rules can result in immediate disqualification from the examination, cancellation of your result even after the exam if malpractice is discovered later, and potential bar from appearing in future AOR examinations. The Supreme Court takes examination integrity very seriously given the responsibility AORs bear in Supreme Court practice.

Success Rate and Exam Pass Percentage Analysis

The AOR examination has one of the lowest pass rates among legal examinations in India, reflecting the high standards the Supreme Court maintains for allowing advocates to practice before it. Understanding these statistics helps you appreciate the examination’s difficulty and the achievement of those who successfully clear it.

Approximately 80% of candidates fail the AOR examination, meaning only about 20% of those who appear actually pass in any given year. Out of roughly 1,000-1,200 candidates who appear for the examination annually, only about 200-250 successfully clear all four papers and meet both the individual paper and aggregate passing criteria. This low pass rate isn’t because the examination is designed to fail people arbitrarily, it’s because the examination genuinely tests specialized knowledge and skills that many candidates haven’t adequately prepared for.

The reasons for such high failure rates are multiple. Many candidates underestimate the examination’s difficulty and appear without adequate preparation, thinking their general legal knowledge or High Court practice experience will suffice. Others focus heavily on theoretical Supreme Court Rules study but lack practical understanding of how those rules apply in real Supreme Court practice. Some candidates may pass three papers but fail one paper, leading to overall failure despite strong performance elsewhere due to the individual paper passing requirement.

The passing rate varies slightly year to year depending on the difficulty level of that year’s question papers and the quality of the candidate pool, but it consistently remains in the 15-25% range. Being among the successful 20% requires dedicated preparation, systematic study, practical training experience that reinforces theoretical knowledge, and often multiple months of focused preparation while managing your ongoing legal practice or other professional commitments.

Detailed AOR Exam Syllabus 2025

Paper I: Supreme Court Practice and Procedure

Paper I is the foundational paper of the AOR examination and arguably the most important for your future AOR practice. This paper tests your comprehensive knowledge of Supreme Court Rules, 2013, procedural law specific to the apex court, filing requirements, and practical scenarios you’ll encounter regularly in Supreme Court practice.

The syllabus covers the constitutional provisions governing Supreme Court jurisdiction, specifically Articles 32, 129, 132, 133, 134, 136, 137, 141, 142, 143, and 145, 317 of the Constitution. These aren’t just articles to memorize; you must understand their practical application through relevant case law.

The Supreme Court Rules, 2013 form the backbone of this paper, and you need to know them inside out. Beyond this, the syllabus includes the Code of Civil Procedure (relevant provisions), Limitation Act, 1963, and general principles from the Court Fees Act, 1870. The Supreme Court also has a 280 page Handbook on Practice and Procedure which you must be thorough with for this paper.

Paper II: Drafting (Legal Documents and Petitions)

Paper II tests your ability to draft the various legal documents and petitions required in Supreme Court practice with proper format, legal soundness, and persuasive argumentation. This is a practical skill-based paper where your drafting competence is directly assessed through actual drafting exercises rather than theoretical questions about drafting principles.

Paper II tests your ability to draft various petitions and applications that AORs routinely prepare. The official syllabus mentions:

- Petitions for Special Leave and Statements of Cases etc.

- Decrees & Orders and Writs etc.

The syllabus includes petitions of appeal; plaint and written statement in a suit under Article 131 of the Constitution of India; review petitions under Article 137 of the Constitution of India; transfer petitions under Section 25 of the Civil Procedure Code, Article 139 of the Constitution of India and Section 406 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; contempt petitions under Article 129 of the Constitution of India; interlocutory applications including applications for bail, condonation of delay, exemption from surrendering, revocation of special leave etc.

Paper III: Advocacy and Professional Ethics

Paper III examines your understanding of professional conduct standards, ethical obligations of advocates generally and AORs specifically, and the principles of effective advocacy that guide Supreme Court practice. This paper tests both your knowledge of formal rules governing professional conduct and your judgment in applying ethical principles to practical scenarios.

The syllabus includes:

- The concept of a profession; Nature of the legal profession and its purposes; Connection between morality and ethics; Professional Ethics in general:- definitions, general principles, seven lamps of advocacy, public trust doctrine, exclusive right to practice in Court;

- History of legal profession in India and relevant statutes.

- Law governing the profession and its relevance and scope; professional excellence and conduct. Professional, criminal and other misconduct and punishment for it (Section 35 and 24(A) and other provisions of the Advocates Act, 1961 and prescribed code of conduct); Duty not to strike; Advertisement/ Solicitation.

- The rules of the Bar council of India on the obligations and duties of the profession, need to shun sharp practices and commercialisation of the profession and the role of the Bar in promotion of legal services under the constitutional scheme of providing equal justice. Role of Bar Council in regulating ethics. Bar Council Rules Chapter II Standard of professional conduct and Etiquette. Different duties of an advocate including categories laid down in the Bar Council Rules on ethics. Conflict between duties and law to resolve them. Difference between breach of ethics and misconduct and negligence, misconduct and crime.

- Comparative study of the profession and ethics in various countries, and their relevance to the Bar.

- Perspectives on the role of the profession in the adversary system and critiques of the adversary system vis a vis ethics.

- Issues of advocacy in the criminal law adversarial system, the zealous advocacy in the criminal defense setting and prosecutorial ethics.

- Lawyer client relationship, confidentiality and issues of conflicts of interest (Section 126 of the Evidence Act); Counseling, negotiation and mediation and their importance to administration of justice. Mediation Ethical Consideration; Amicus Curiae Ethical Consideration.

- Current developments in the organization of the profession, firms, companies etc. and application of ethics.

- Special role of the profession in the Supreme Court practice and its obligations to administration of justice. Adjournments; Duties of Advocate on Record; Supervisory role of the Supreme Court; Contempt of Courts.

Paper IV: Leading Cases

Paper IV tests your knowledge of landmark Supreme Court judgments that form the foundation of Indian jurisprudence across various areas of law.

It covers 86 (Volume I, Volume II and Volume III) leading constitutional cases specified by the Supreme Court in its official notification. It tests a candidates indepth knowledge of significant Supreme Court judgements specifically their ability to understand the underlined legal principles (ratio decidendi) and their practical application to factual situations.

Some absolutely essential constitutional cases include Holiness Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalavaru v. State of Kerala [ SC 1973] (basic structure doctrine), Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [SC 1978] (Article 21 expansion), Minerva Mills Ltd. & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors.[ SC 1981] (judicial review), Indra Sawhney and Ors. Etc. Etc. v. Union of India and Ors. Etc. Etc. [ SC 1992] (reservations), S.R. Bommai and Ors. v. Union of India and Ors. [SC 1994] (federalism and President’s Rule), Vishaka and Ors. v. State of Rajasthan and Ors. [ SC 1997] (sexual harassment), Navtej Singh Johar & Ors. v. Union of India Thr. Secretary Ministry of Law and Justice [ SC 2018] (Section 377), Shreya Singhal v. Union of India [ SC 2015] (free speech), and dozens more covering every aspect of constitutional law.

Roles and Responsibilities of Advocate on Record

What are the Primary Duties of an AOR?

Being an AOR isn’t just about having filing privileges, it comes with substantial responsibilities and duties that you owe to your clients, the Court, and the larger justice system. Understanding these duties before you become an AOR helps you assess whether you’re prepared for this level of professional responsibility and commitment.

As an AOR, you are considered an officer of the Supreme Court, not merely a private legal practitioner. This designation carries special significance because it means you owe duties to the Court itself that go beyond your duties to clients. The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that AORs cannot merely lend their names to petitions without genuine involvement, you must take actual responsibility for the cases you file and the documents you sign.

Your primary duty is ensuring the accuracy and completeness of all petitions, applications, and documents you file before the Supreme Court. You’re personally responsible for verifying facts stated in petitions, checking that legal grounds are properly formulated, ensuring all required documents are annexed, and confirming that procedural requirements are met. Even if a junior advocate or colleague drafts a petition, once you sign it as the AOR, you bear full responsibility for its contents.

You have a duty of complete honesty and candor toward the Court. This means disclosing all material facts whether favorable or unfavorable to your client’s case, not making misleading statements even through omission, bringing contrary precedents to the Court’s notice if they’re directly applicable, and correcting any errors or misstatements you discover even after filing. This duty sometimes creates tension with your duty to represent clients zealously, but as an officer of the Court, honesty always takes precedence.

Filing Cases and Vakalatnama Submission

Filing cases in the Supreme Court is your exclusive right as an AOR, and it’s also your primary function in most client relationships. Let me explain the process and your specific responsibilities regarding filings and vakalatnama submission so you understand what this central AOR duty involves.

The vakalatnama is the first and most important document in any Supreme Court matter. It’s the authorization from the client appointing you as their AOR to represent them before the Supreme Court. Only an AOR can file a vakalatnama in the Supreme Court, this is your exclusive power. The vakalatnama must be on the prescribed format, properly executed by the client or their authorized representative, and filed along with the main petition at the time of initial filing.

When filing a new matter, you need to prepare several components: the main petition (SLP, writ, suit, etc.) drafted according to prescribed formats, the vakalatnama executed by the client, synopsis of arguments (concise summary of your case), list of dates and events in chronological order, and all supporting documents properly paginated and indexed as annexures. Everything must comply with Supreme Court Rules, 2013 regarding paper size, font, margins, binding, and other formatting requirements.

The filing process involves submitting your documents to the Supreme Court Registry where officials scrutinize them for completeness and compliance. If any defects are found such as missing documents, formatting errors, improper execution of vakalatnama, insufficient court fees, the Registry issues a defect memo. You’re responsible for curing these defects within the stipulated time frame. Failure to cure defects leads to rejection of your filing, which can have serious consequences for your client including limitation issues.

Your signature as AOR on the petition is your professional certification that you’ve verified the contents, ensured compliance with all requirements, and take responsibility for the accuracy of statements made. This isn’t a casual signature, it’s a representation to the Supreme Court that you’ve exercised due diligence.

Client Representation and Court Appearance

While filing cases is your exclusive technical function, representing clients effectively in Supreme Court proceedings is equally important. Your role as an AOR involves more than just procedural mechanics, you’re the primary point of contact between your client and India’s highest court, responsible for protecting their legal interests and ensuring their voice is heard.

You’re required to appear personally or through another AOR when your matters are listed for hearing. The Supreme Court has strongly criticized AORs who file matters but never appear in court, treating their role as purely mechanical. While you can instruct a Senior Advocate or other counsel to argue the matter, you or another AOR from your firm must be present in court when the case is called to handle procedural aspects and take instructions.

Your responsibilities during hearings include submitting appearance slips duly signed by you, bringing the case records and relevant documents to court, taking detailed notes of proceedings and judicial observations, obtaining certified copies of orders passed, communicating court orders to clients promptly, and following up on directions given by the bench. If the Court gives you time to file additional documents or written submissions, you’re responsible for ensuring compliance within the time granted.

Communication with clients is an ongoing responsibility throughout the case. You need to keep clients informed about case status, hearing dates, court observations, and progress. You should explain legal issues and court orders in terms clients can understand, advise them on the realistic prospects of their case, and manage their expectations. When the Court asks for instructions, for example, whether client wants to pursue a particular remedy, you must obtain clear instructions and communicate them accurately to the Court.

If you’re unable to attend a hearing due to genuine reasons such as illness, another urgent matter, personal emergency, you should arrange for another AOR to appear on your behalf or seek adjournment through proper procedure. Unexplained absence when your matter is listed reflects poorly on you professionally and can invite the Court’s displeasure. Building a professional reputation in Supreme Court practice requires consistent, reliable attendance and diligent case handling.

Document Management and Record Maintenance

AORs are required to maintain meticulous records of all their Supreme Court matters, not just for professional best practices but as a mandatory requirement under Supreme Court Rules, 2013. Proper document management and record-keeping are essential for effective AOR practice and compliance with your regulatory obligations.

You must maintain complete case files for every matter you handle, including all original documents provided by clients, all documents filed in court with date-stamped copies, all orders passed by the Court with certified copies, correspondence with clients and other parties, fee receipts and financial records related to the matter, and notes of all court proceedings and hearings. These files should be organized systematically so you can quickly retrieve information when needed.

Supreme Court Rules, 2013 require AORs to maintain books of account showing money received from clients and money paid on their account, separately identifying each client’s financial transactions. You should maintain trust accounts for client funds, separate from your personal funds. When you file a bill of costs for taxation, you must certify the fees received or agreed to be received from your client. Proper accounting isn’t optional, it’s a regulatory requirement.

You’re responsible for ensuring safe custody of client documents and maintaining confidentiality of client information. Original documents provided by clients for Supreme Court proceedings should be carefully preserved and returned to clients after the matter concludes. Losing client documents or confidential information can expose you to both professional disciplinary action and legal liability for negligence.

Case tracking and deadline management are critical aspects of AOR practice. You need systems to track hearing dates, deadlines for filing documents, limitation periods for filing appeals or applications, and review/curative petition timelines. Missing a crucial deadline due to poor record-keeping can have devastating consequences for your client’s case and can expose you to professional negligence claims.

Career Prospects and Professional Growth

What Career Opportunities Open Up After Becoming AOR?

Becoming an AOR opens numerous career opportunities beyond just filing Supreme Court cases. The designation is prestigious enough that it transforms your entire legal career trajectory, even if you continue practicing primarily at other levels. Let me outline the diverse career paths and opportunities that become accessible once you earn the AOR designation.

The most obvious opportunity is building a Supreme Court-focused litigation practice. As an AOR, you can develop a practice handling appellate matters from High Courts across India, constitutional cases, special leave petitions, and original jurisdiction matters. Over time, you can specialize in specific areas such as constitutional law, tax law, service matters, criminal appeals, civil litigation, intellectual property, or any other specialization. Clients and referring advocates seek out AORs with demonstrated expertise in particular areas.

You can establish a hybrid practice combining Supreme Court work with your existing High Court or trial court practice. Many successful AORs maintain practices at multiple levels, they handle trial court and High Court matters in their home jurisdiction while taking on Supreme Court matters when cases reach the apex court. This multi-level practice model maximizes your client relationships because you can represent the same client from trial court all the way to the Supreme Court, providing continuity and comprehensive service.

Corporate and government legal roles often value AOR designation. Many large corporations and Public Sector Undertakings prefer hiring in-house counsel with AOR designation because it allows them to handle their own Supreme Court matters rather than always outsourcing to external AORs. Government departments similarly value law officers with AOR designation for handling their Supreme Court litigation.

Law Firm Partnerships and Practice Development

The path to law firm partnership often becomes smoother once you have AOR designation because you bring a valuable credential and capability to the firm.

Large law firms value AORs because they provide firms the capability to handle Supreme Court litigation without depending on external counsel.

Some AORs establish boutique Supreme Court-focused firms, building practices entirely around appellate and constitutional litigation. Law firms where all partners are AORs can even register as AOR firms, giving the firm itself AOR status. This allows seamless client service where the firm relationship continues from lower courts through Supreme Court proceedings. A few prominent law firms in India have achieved this AOR firm registration, giving them distinctive positioning in the market.

Building your own firm around your AOR designation requires strategic practice development. You need to develop referral relationships with High Court advocates and trial lawyers who will refer matters to you when cases reach the Supreme Court. You need to market your AOR capability effectively to potential clients and referral sources. You need to build a team of junior associates and trained advocates who can assist with research, drafting, and case management. Over time, successful AOR practices can grow into substantial firms.

The financial aspects of law firm practice as an AOR are attractive. Partners in firms with strong Supreme Court practices often earn significantly more than sole practitioners because the firm structure allows handling higher volumes of matters. Firms can also command premium fees because they offer complete litigation solutions from trial through Supreme Court appeals. Building equity in a successful law firm provides long-term financial security beyond just current income from practice.

Whether joining an existing firm or building your own, the AOR designation creates partnership opportunities that might not otherwise be available.

Path to Senior Advocate Designation

The Senior Advocate designation is the highest professional distinction in Indian legal practice, and being an AOR positions you well for eventually receiving this honor. While Senior Advocates and AORs serve different functions, many Senior Advocates began as AORs and developed their reputation through years of Supreme Court practice.

Once designated as a Senior Advocate, your role changes significantly. You can no longer file cases or handle procedural work, you become purely an arguing counsel focused on oral advocacy. You work with AORs who handle the filing and procedural aspects while you focus on arguments. Senior Advocates command premium fees, often significantly higher than even successful AORs, reflecting their specialized expertise and standing.

Not every AOR seeks Senior Advocate designation, many choose to remain AORs throughout their careers because they value the complete control over their practice that AOR status provides. Being an AOR allows you to handle cases from filing through final arguments without depending on others, build direct client relationships, and control the financial aspects of your practice. Both paths offer successful, fulfilling careers in Supreme Court practice.

Judicial Appointments and Alternative Career Paths

AOR practice can lead to judicial appointments at higher levels of the judiciary. The experience of Supreme Court practice, familiarity with constitutional law and appellate procedure, and demonstrated professional excellence make AORs attractive candidates for elevation to the High Court bench and occasionally directly to the Supreme Court bench.

Elevation directly from the Bar to the Supreme Court bench is rarer but does happen. The Supreme Court collegium occasionally elevates outstanding advocates with exceptional legal ability and standing to the apex court bench. Being a successful, respected AOR practicing before the Supreme Court for many years positions you as a potential candidate if you have demonstrated extraordinary legal scholarship and professional distinction.

For example, Justice Indu Malhotra became an AOR in 1988 and, thereafter, she was designated as a Senior Counsel by the Supreme Court in 2007, eventually becoming the first woman to be appointed as a Judge of the Supreme Court directly from the Bar in 2018.

Alternative career paths beyond litigation also open up with AOR designation. Legal academia values faculty members with practical Supreme Court experience, you could transition to teaching constitutional law or procedure at leading law schools while maintaining limited AOR practice. Arbitration is another avenue – experienced AORs often serve as arbitrators in high-value commercial disputes, using their legal expertise and dispute resolution skills in a different forum.

Government positions sometimes seek out experienced AORs. Positions like Solicitor General, Additional Solicitor General, or legal advisors to government departments often go to distinguished AORs with proven Supreme Court expertise.

How Much Do Advocates on Record Earn?

Let me address the question that’s probably at the top of your mind if you’re considering becoming an AOR: what’s the earning potential? The financial aspects of AOR practice are attractive, though income varies significantly based on experience, practice area, reputation, and work volume. Let me give you realistic income expectations at different career stages.

For fresh AORs in their first 1-2 years of practice, income typically ranges from ₹3-5 lakh annually if you’re building practice from scratch. This may seem modest considering the effort to become an AOR, but it’s just the starting point. Fresh AORs typically earn from smaller matters, assisting senior AORs with drafting and filing work, and gradually building their own client base. If you already have an established High Court practice before becoming an AOR, your income will be higher because you can bring existing clients’ Supreme Court matters to your new AOR practice.

Mid-level AORs with 3-7 years of Supreme Court practice typically earn ₹12-20 lakh annually from Supreme Court work alone. By this stage, you’ve developed referral relationships, established a reputation, and handle a steady flow of matters. You’re commanding better fees, handling more complex cases, and spending less time on small matters. Some mid-level AORs earn considerably more than this range if they’re in high-demand practice areas or have developed strong corporate or government client relationships.

Senior AORs with 8-15 years of established practice can earn ₹30-50+ lakh annually, and highly successful senior practitioners may earn substantially more – sometimes several crores per year. At this level, you’re a recognized expert in your practice area, clients seek you out specifically, you can be selective about matters you take on, and you command premium fees. You may have a team of junior associates working under you, allowing you to handle higher volumes while maintaining quality.

These income figures represent earning from Supreme Court work specifically, and many AORs maintain parallel High Court or trial court practices that generate additional income. If you’re a successful High Court advocate who adds AOR designation, your total income combines both practices. Delhi-based AORs generally earn 20-30% more than those based outside Delhi for similar experience and work volume because Delhi location provides easier access to clients, courts, and networking opportunities.

Fee Structure and Earning Potential

The Supreme Court Rules, 2013, establish a formal fee structure for Supreme Court case filings. In practice, however, the actual charges differ significantly from these prescribed amounts.

The AORs typically charge ₹15,000–₹20,000 merely to file the vakalatnama or submit a petition. When more extensive drafting is required, fees increase accordingly.

For drafting a single Supreme Court petition, AORs usually charge a base rate of ₹20,000–₹25,000, though reduced rates may apply when they assist senior lawyers rather than serving clients independently.