The Advocate on Record Exam is one of the most challenging and prestigious milestones for lawyers aspiring to practice in the Supreme Court of India. This comprehensive guide explains what the AOR exam is, its eligibility, syllabus, exam pattern, preparation strategy, and why qualifying as an AOR can transform your legal career.

Table of Contents

If you have ever dreamed of walking into the Supreme Court with your own name on the case file, then the Advocate on Record (AOR) exam is your golden ticket.

It’s not just another test, it’s the gateway to an elite league of barely 3,789 advocates who hold exclusive rights to practice before India’s highest court.

Sounds glamorous? Sure. But the pass rates are historically low. Clearing it demands discipline, strategy, and a deep understanding of what the examiners are really testing.

In this guide, I’m breaking down everything you need to know, eligibility rules, paper wise syllabus, what the examiners look for, and how to prepare smartly without burning out.

By the end, you’ll have a clear roadmap from your State Bar enrollment to signing your first petition in the Supreme Court as an Advocate on Record.

Are you excited? Let us begin.

But before we get into the syllabus and strategies, let’s answer the question every ambitious lawyer secretly asks, what are the rewards after clearing the exam.

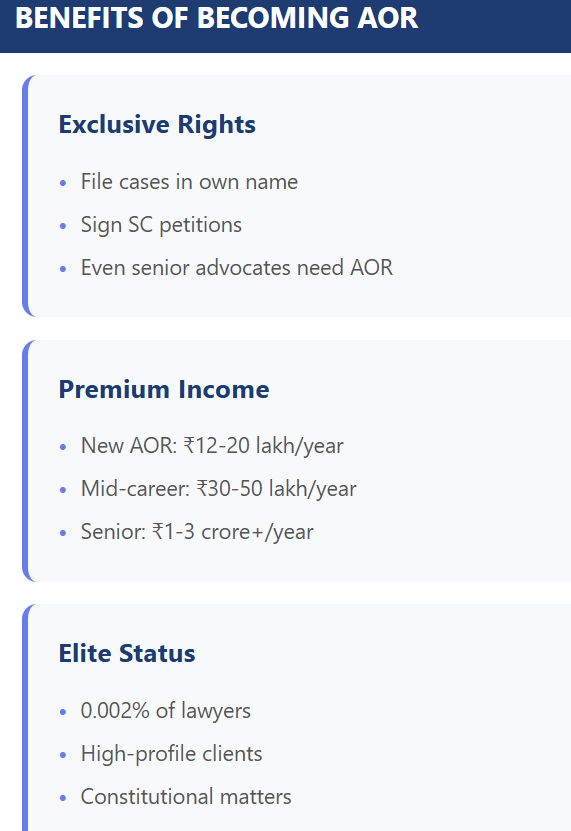

What are the Rewards of Cracking the Advocate on Record Exam?

Becoming an Advocate on Record isn’t merely an addition to your professional credentials, it fundamentally transforms your legal practice and career trajectory.

The AOR designation comes with exclusive Supreme Court practice rights that set you apart from the vast majority of legal practitioners in India. Understanding these rewards helps you evaluate whether pursuing this challenging qualification aligns with your career aspirations and justifies the significant time investment required for preparation.

Let me walk you through the concrete professional advantages that come with clearing the AOR exam, from exclusive practice rights to premium client access and enhanced income potential.

Exclusive Right to File and Argue in the Supreme Court

As an Advocate on Record, you gain the exclusive statutory right to file cases directly before the Supreme Court of India in your own name. Under Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules 2013, only AORs can sign and file pleadings, petitions, and applications before the apex court.

This means that even senior advocates and lawyers with decades of High Court experience cannot file cases in the Supreme Court without engaging an AOR.

Your signature becomes the gateway to Supreme Court litigation, positioning you as an essential intermediary in India’s highest judicial forum.

Command Premium Fees and High Profile Clients

The scarcity of AORs, representing roughly 0.002% of India’s legal profession, creates significant demand for your services.

When clients need Supreme Court representation, they have limited options, allowing you to command premium fees that far exceed typical High Court or trial court rates.

The AOR salary landscape in India offers one of the most attractive income trajectories in legal practice. Starting from approximately ₹12-20 lakh in your first years, you can realistically build to roughly ₹30-50 lakh by mid-career and cross around ₹1-3 crore+ annually as a senior practitioner with the right strategy, specialization, and client relationships.

Beyond immediate fee advantages, the AOR designation attracts high profile clients including corporations, government entities, and individuals with significant constitutional or commercial matters.

These clients specifically seek AORs for their Supreme Court matters, creating a self-selecting client base that recognizes and values your specialized expertise.

Your practice naturally elevates toward more complex, higher stakes litigation that shapes legal precedent and policy, providing both intellectual satisfaction and professional prestige alongside enhanced earnings.

Advocate on Record Exam Eligibility Requirements

Before diving into exam preparation, you need to verify that you meet the Supreme Court’s eligibility criteria for appearing in the AOR examination.

These requirements are designed to ensure that only advocates with adequate legal education, professional experience, and practical Supreme Court training attempt the exam. Understanding each criterion in detail helps you plan your timeline accurately and avoid application rejections.

The eligibility framework has three primary components: educational qualifications, practice experience, and mandatory training under a senior AOR.

Let me break down each requirement so you can assess your current standing and determine when you’ll be eligible to appear for the exam.

Educational Qualification Requirements

LLB Degree from BCI Approved Institution

You must hold a Bachelor of Laws (LLB) degree from an institution recognized by the Bar Council of India.

This includes both three-year LLB programs and five-year integrated BA LLB/BBA LLB programs from any university approved by the BCI.

Your law degree must have been completed and conferred before you can calculate your practice experience eligibility.

All India Bar Examination (AIBE) Requirement

Successful completion of the All India Bar Examination (AIBE) conducted by the Bar Council of India is a prerequisite for AOR exam eligibility.

The AIBE certificate validates your basic competence in core legal subjects and professional ethics.

Since AIBE became mandatory in 2010, you must have cleared this examination before enrolling with any State Bar Council. Your AIBE qualification forms part of your eligibility documentation when applying for the AOR exam, so ensure you have your AIBE certificate accessible when preparing your application.

Practice Experience Requirements

Bar Council Enrollment and Minimum Practice Duration

You must have completed a minimum of four years of continuous practice as an enrolled advocate before the date of the AOR examination.

This four-year period is calculated from your enrollment date with any State Bar Council in India, not from your law degree completion date or AIBE passing date.

For example, if you enrolled with the State Bar Council on January 15, 2020, you become eligible to appear for the AOR exam only from January 16, 2024 onwards. Importantly, this practice experience need not be exclusively before the Supreme Court, your High Court, District Court, or tribunal practice experience counts toward this requirement.

Training Requirements Under a Senior AOR

Beyond educational qualifications and practice experience, the Supreme Court mandates specialized training under an experienced Advocate on Record before you can attempt the exam.

This training requirement ensures you gain practical exposure to Supreme Court procedures, filing requirements, and litigation practices before seeking independent AOR status.

The training framework involves identifying a suitable senior AOR, obtaining formal training approval, completing one full year under their guidance, and securing a completion certificate. Let me explain each component of this critical eligibility requirement.

Mandatory One Year Training Under a Senior AOR

You must complete one continuous year of training under an Advocate on Record who has been enrolled as an AOR for at least ten years.

This training period must commence only after you’ve completed four years of practice as an advocate, you cannot begin AOR training during your first four years of practice.

The training is designed to familiarize you with Supreme Court specific procedures including filing processes, Registry requirements, drafting standards, and courtroom etiquette that differ significantly from High Court or trial court practice.

During this training year, you’ll typically assist your supervising AOR with drafting Supreme Court petitions, researching case law, preparing for appearances, managing Registry objections, and understanding the practical workflow of Supreme Court litigation.

The training is hands on and practice oriented rather than theoretical classroom instruction. You should ideally work closely with your AOR supervisor on actual Supreme Court matters to gain authentic exposure to the procedures you’ll need to master for both the exam and your future independent practice.

Completion Certificate issued by Senior AOR

At the conclusion of your one year training period, your supervising AOR must issue a formal Training Completion Certificate confirming that you’ve satisfactorily completed the training program under their guidance.

This certificate is a mandatory document that must accompany your AOR exam application, without it, the Supreme Court will not accept your application form.

The certificate should be issued on the AOR’s letterhead, include specific training start and end dates, and contain their AOR registration number. Ensure you maintain regular communication with your training AOR and request the completion certificate well before the exam application deadline to avoid last minute complications.

You can find the sample templates here: AOR Training Intimation Documents.

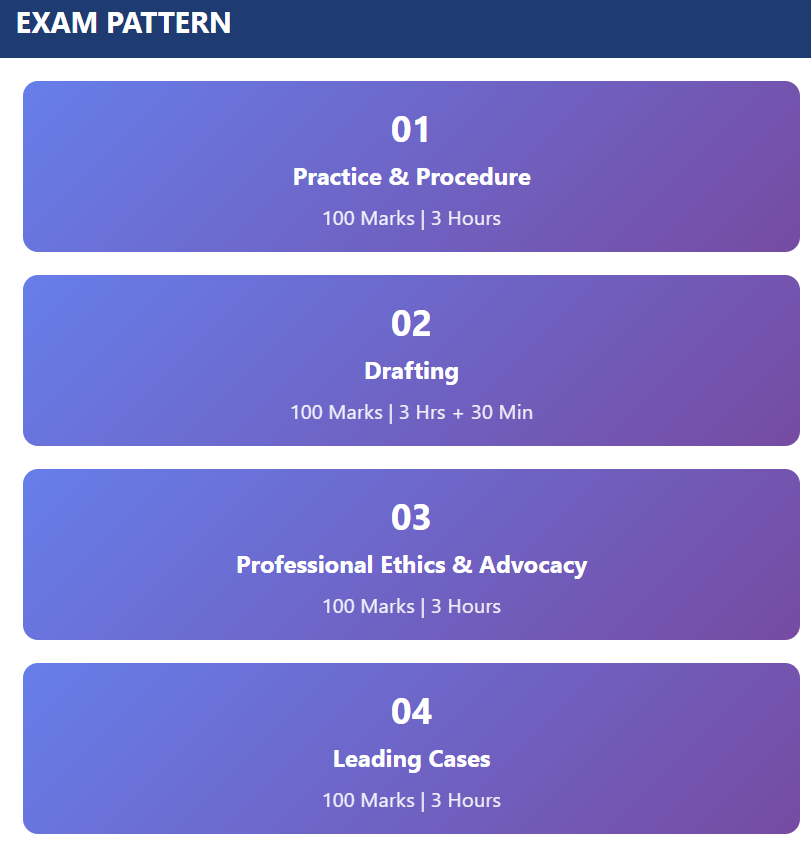

Advocate on Record Exam Pattern and Structure

The AOR exam differs significantly from traditional law school examinations or other professional certifications in its structure, duration, and assessment methodology.

The Supreme Court designs this exam to test not theoretical knowledge but practical application of Supreme Court procedures, drafting skills, ethical judgment, and familiarity with landmark constitutional and legal principles.

Let me walk you through the complete exam pattern including timing, paper structure, passing criteria, and attempt restrictions that govern your examination journey.

When and How is the Advocate on Record Exam Conducted?

Conducted in May-June of Each Year

The Supreme Court typically conducts the AOR examination annually during May-June, though exact dates vary each year based on the Court’s schedule and administrative considerations.

Official notification for the exam is usually issued 2-3 months in advance, providing details about application deadlines, exam dates, and required documentation. The application window typically remains open for 15-20 days, requiring you to act promptly once the notification is released.

Exam Mode: Offline Pen and Paper Test

The AOR examination is conducted exclusively in offline mode using traditional pen and paper format at the Supreme Court premises in New Delhi.

Unlike many modern professional exams that have transitioned to computer based testing, the Supreme Court maintains the written examination format to assess your handwriting legibility, drafting presentation, and ability to structure arguments without digital assistance.

Each Paper: 100 Marks, 3 Hours Duration, Plus 30 Minutes Reading Time

Each of the four examination papers carries 100 marks and must be completed within three hours of writing time. Additionally, you receive 30 minutes of reading time for the drafting paper.

The three hour writing window is intensive, requiring you to balance comprehensive answers with time management, as most papers contain multiple questions demanding detailed responses within the allocated timeframe.

What is the Passing Criteria for Advocate on Record Exam?

60% Aggregate + 50% Minimum in Each Paper

To qualify as an Advocate on Record, you must achieve a minimum aggregate score of 240 marks out of 400 total marks (60%) across all four papers, with a mandatory minimum of 50 marks (50%) in each individual paper.

This dual requirement means you cannot compensate for a weak performance in one paper by scoring exceptionally high in others.

For example, even if you score 90, 85, and 80 in three papers totaling 255 marks, failing to secure 50 marks in the fourth paper will result in overall failure despite your aggregate exceeding 60%.

This stringent criterion ensures candidates demonstrate competence across all aspects of Supreme Court practice rather than excelling in selective areas.

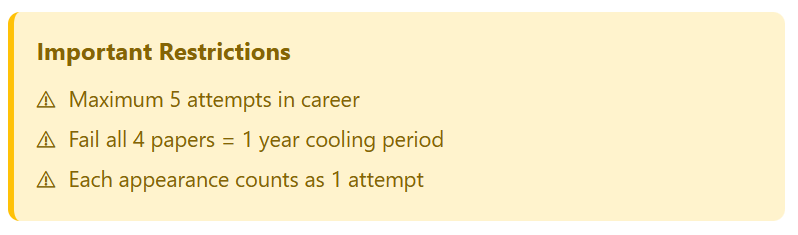

What Happens If You Fail All Four Papers?

If you fail to secure the minimum qualifying marks in all four papers simultaneously, you face a mandatory one year cooling off period before you can re-appear for the examination.

This means you cannot attempt the immediately next scheduled exam and must wait an additional year. For instance, if you appear for the June 2025 exam and fail all four papers, you cannot appear in June 2026, your next eligible attempt would be June 2027 or later.

This consequence makes inadequate preparation particularly costly, emphasizing the importance of attempting the exam only when you’re thoroughly ready.

How Many Times Can You Attempt the Advocate on Record Exam?

Maximum Five Attempts Allowed

The Supreme Court permits a maximum of five attempts at the AOR examination over your career.

Each time you appear for the exam (regardless of whether you write all papers or only some), it counts as one attempt against this limit.

If you clear some papers and need to re-appear only for failed papers, that subsequent appearance still counts as a separate attempt.

Once you’ve exhausted all five attempts without qualifying, you cannot appear for the AOR exam again, effectively closing the pathway to independent Supreme Court practice for you.

Should You Attempt If Not Fully Prepared?

Given the five-attempt restriction and the one year penalty for failing all papers, attempting the exam without thorough preparation is strategically unwise.

Many advocates make the mistake of appearing prematurely, reasoning that exam experience itself is valuable, but this costs you one precious attempt and potentially delays your qualification by a full year.

I recommend attempting the exam only when you have: (1) completed comprehensive syllabus coverage for all four papers, (2) practiced previous years’ question papers under timed conditions, (3) received feedback on your draft answers from experienced AORs, and (4) completed at least three full length mock tests simulating actual exam conditions.

If you’re not confident about these preparation benchmarks, it’s better to defer your attempt to the next cycle.

Syllabus of Advocate on Record Exam

The AOR examination syllabus is distributed across four distinct papers, each testing different competencies essential for Supreme Court practice.

Unlike comprehensive bar examinations that test general legal knowledge, the AOR syllabus is specifically focused on Supreme Court procedures, practical drafting skills, professional ethics, and landmark jurisprudence.

Understanding what each paper covers helps you allocate preparation time effectively and identify which aspects require deeper focus based on your existing strengths and weaknesses.

Let me provide you with a clear breakdown of each paper’s content scope so you can begin structuring your study plan.

What is Covered in the Syllabus of Paper 1: Practice and Procedure?

Paper I tests your understanding of Supreme Court jurisdiction under Articles 136 (Special Leave Petitions), 137 (Review jurisdiction), 141 (Law declared by Supreme Court binding), and 142 (Complete justice powers), along with practical application of Supreme Court Rules 2013 in their entirety, and relevant sections of the Code of Civil Procedure, Limitation Act, and Court Fees Act.

You can refer to my article on the AOR Exam Syllabus to check out the detailed syllabus.

What is Covered in the Syllabus of Paper 2: Drafting?

The official syllabus mentions:

- Petitions for Special Leave and Statements of Cases, etc.

- Decrees & Orders and Writs, etc.

This is to clarify that the syllabus includes petitions of appeal; plaint and written statement in a suit under Article 131 of the Constitution of India; review petitions under Article 137 of the Constitution of India; transfer petitions under Section 25 of the Civil Procedure Code, Article 139 of the Constitution of India and Section 406 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973; contempt petitions under Article 129 of the Constitution of India; interlocutory applications including applications for bail, condonation of delay, exemption from surrendering, revocation of special leave etc.

What is Covered in the Syllabus of Paper 3: Professional Ethics and Advocacy?

Paper III covers the following topics:

- The concept of a profession; Nature of the legal profession and its purposes; Connection between morality and ethics; Professional Ethics in general:- definitions, general principles, seven lamps of advocacy, public trust doctrine, exclusive right to practice in Court;

- History of the legal profession in India and relevant statutes.

- Law governing the profession and its relevance and scope; professional excellence and conduct. Professional, criminal and other misconduct and punishment for it (Section 35 and 24(A) and other provisions of the Advocates Act, 1961 and prescribed code of conduct); Duty not to strike; Advertisement/ Solicitation.

- The rules of the Bar Council of India on the obligations and duties of the profession need to shun sharp practices and commercialisation of the profession and the role of the Bar in the promotion of legal services under the constitutional scheme of providing equal justice. Role of the Bar Council in regulating ethics. Bar Council Rules Chapter II Standard of professional conduct and Etiquette. Different duties of an advocate, including categories laid down in the Bar Council Rules on ethics. Conflict between duties and the law to resolve them. Difference between breach of ethics and misconduct and negligence, and misconduct and crime.

- Comparative study of the profession and ethics in various countries, and their relevance to the Bar.

- Perspectives on the role of the profession in the adversary system and critiques of the adversary system vis-à-vis ethics.

- Issues of advocacy in the criminal law adversarial system, zealous advocacy in the criminal defense setting and prosecutorial ethics.

- Lawyer client relationship, confidentiality and issues of conflicts of interest (Section 126 of the Evidence Act); Counseling, negotiation and mediation and their importance to the administration of justice. Mediation Ethical Consideration; Amicus Curiae Ethical Consideration.

- Current developments in the organization of the profession, firms, companies, etc. and application of ethics.

- Special role of the profession in the Supreme Court practice and its obligations to the administration of justice. Adjournments; Duties of Advocate on Record; Supervisory role of the Supreme Court; Contempt of Courts.

What is Covered in the Syllabus of Paper 4: Leading Cases?

The Supreme Court provides all 86 leading cases as downloadable PDFs in three volumes (Volume I, Volume II and Volume III) on the AOR examination page. Download these volumes and read from official sources rather than relying on third party summaries or commentaries. The official PDFs include headnotes summarizing the main propositions established by each case.

Essential Study Materials and Resources for Advocate on Record Exam

Selecting the right study materials significantly impacts your preparation efficiency and exam performance.

Unlike general competitive exams with standardized textbooks, AOR exam preparation requires combining Supreme Court specific resources, authoritative commentaries, statutory compilations, and case law databases.

The challenge lies not in scarcity of materials but in identifying which resources provide the most value for the time invested.

Let me guide you through the essential study resources, from foundational books to previous question papers and coaching options, helping you build a comprehensive preparation library.

Which Books Should You Read for Advocate on Record Exam Preparation?

While official sources should be your primary materials, certain textbooks and commentaries aid understanding. For Paper I (Practice & Procedure), the standard reference is “Supreme Court Practice and Procedure” by Prof. B.R. Agarwala or similar comprehensive commentaries on Supreme Court Rules.

These books explain each rule with illustrations, case laws, and practical application examples. Additionally, a good commentary on the Code of Civil Procedure (like Mulla’s CPC or C.K. Takwani’s CPC) helps in understanding CPC provisions applicable to Supreme Court practice.

For Paper II (Drafting), there’s no substitute for studying actual Supreme Court petitions and applications filed in real cases. However, you can refer to “DRAFTING for Supreme Court Paper II Advocate-on-Record (AOR) Examination” by Dr. M. K. Ravi.

More valuable than textbooks is obtaining sample drafts from senior AORs or through your training with an AOR, these show actual formats used in practice. Remember that Supreme Court drafting formats differ from High Court/District Court formats, so ensure your samples are Supreme Court-specific.

For Paper III (Professional Ethics), “Sanjiva Row’s Advocate Act” and “Law of Contempt” by Samraditya Pal are standard references, though they’re comprehensive treatises.

You don’t need to read these cover to cover; focus on chapters dealing with professional misconduct, standards of conduct, and contempt provisions. The Bar Council’s own rules pamphlet is more concise and sufficient for exam purposes.

For Paper IV (Leading Cases), no textbooks are needed beyond the actual judgments, though constitutional law textbooks by M.P. Jain or V.N. Shukla provide useful background for understanding constitutional cases in context.

Are Previous Year Question Papers Available?

The Supreme Court of India officially publishes AOR examination question papers from the year 2007 on its website, making them freely accessible to all aspirants.

This is a significant advantage compared to many other professional examinations where past papers remain confidential. You can find these papers at the official Supreme Court website under the AOR Examination section.

Previous years’ question papers are invaluable for understanding the examination pattern, question style, and topic emphasis across different years.

Once you obtain the previous papers, analyzing them systematically reveals patterns in the types of questions asked, the specific Supreme Court Rules orders most frequently tested, commonly appearing ethical scenarios, and the case law emphasis areas.

Pattern Analysis – What Types of Questions Are Asked?

Paper I typically contains a mix of situation based questions, concept based questions, and direct questions on Supreme Court Rules.

Paper II contains two compulsory parts, Part A and Part B. Part A focuses on drafting petitions or specific components (e.g., synopsis, grounds, prayers) based on detailed legal fact patterns involving various legal scenarios. Part B contains question that builds on the drafting skills tested in Part A but may involve a more complex or specialized legal issue.

Paper III is a descriptive paper focused on advocacy, professional ethics, BCI Rules, Advocates Act, and Supreme Court judgments. Questions are predominantly analytical, requiring explanations with case laws, ethical reasoning, and balanced opinions.

Paper IV is generally divided in two parts: Part A questions are long form, analytical essays that demand deep understanding of landmark cases, doctrinal shifts, and their broader implications. Part B questions are short answer, multi part queries that test precise application of law and case law to specific issues (e.g., taxation, arbitration, constitutional provisions).

How to Prepare for the Advocate on Record Exam?

Strategic preparation distinguishes successful candidates from the majority who fail despite adequate knowledge.

The AOR exam demands not just legal knowledge but specific skills: rule memorization and application, time-bound drafting, ethical analysis, and case law synthesis.

Your preparation approach must address each paper’s unique requirements while managing the challenge of studying alongside active legal practice.

Let me walk you through comprehensive, paper-specific preparation strategies that have helped numerous advocates successfully clear the exam in their first attempt.

When Should You Start Preparation?

6 to 12 Months Intensive Preparation Recommended

For most advocates, dedicating 6-12 months of intensive, focused preparation provides adequate time to thoroughly cover all four papers, practice timed answering, and complete multiple mock tests.

If you have prior Supreme Court exposure through your training year or if you’re currently practicing in Supreme Court matters, 6-8 months may suffice.

However, if you’re a High Court or trial court practitioner with limited Supreme Court familiarity, planning for 10-12 months allows you to build foundational knowledge before attempting advanced preparation.

The timeline also depends on daily study hours you can allocate, advocates studying 3-4 hours daily need longer preparation periods than those who can dedicate 5-6 hours daily.

Starting earlier doesn’t necessarily improve outcomes if you lose momentum midway, while starting too late creates pressure that hampers quality preparation.

The optimal approach is beginning your structured preparation approximately 8-10 months before your target exam cycle, allowing time for comprehensive syllabus coverage (4-5 months), intensive revision (2-3 months), and mock test practice (1-2 months). This timeline also provides buffer for unexpected life events or professional commitments that might interrupt your study schedule.

Do not miss to also refer to the Indian Lawyers guide to cracking the Supreme Court AOR Exam for additional guidance.

Can You Prepare While Practicing? Balancing Work and Study

Yes, preparing alongside active practice is not only possible but is the reality for most AOR aspirants.

Very few advocates have the luxury of taking extended study leave. The key lies in creating sustainable study routines that complement rather than compete with your practice.

Early morning hours (5:30-8:00 AM) before court work begins or late evening hours (9:00-11:30 PM) after court work concludes are typically most productive for focused study.

Utilize weekends strategically: dedicate Sundays to intensive study sessions covering new topics, and use Saturday evenings for revision of previously covered material.

During court vacations (typically summer vacation from mid-May to early July), accelerate your preparation by dedicating full days to study.

Communicate your AOR preparation goals to your seniors, colleagues, and clients, most will support reasonable schedule adjustments when they understand you’re working toward professional advancement.

Consider temporarily reducing your case intake 2-3 months before the exam to create more preparation time.

Some advocates find that selective practice, focusing only on high value matters while referring smaller cases to colleagues during the preparation period, creates necessary study space without completely abandoning practice income.

Paper 1 (Practice & Procedure) Preparation Strategy

Paper 1 forms the foundation for understanding Supreme Court practice and typically proves the most challenging paper given its vast syllabus scope.

Allocate approximately 40% of your total preparation time to this paper, as mastering Supreme Court procedures and rules provides context that helps with other papers as well.

Master Supreme Court Rules Orders First, Then Link to Constitution

Begin your Paper 1 preparation by thoroughly studying the Supreme Court Rules 2013, focusing intensively on Appellate Jurisdiction covering civil appeals, criminal appeals, and SLPs), and Original Jurisdiction under Articles 32 and 131, Transfer Petitions, Review, Curative Petitions, and miscellaneous provisions.

Don’t just read these orders, make detailed notes outlining the procedure for each type of petition or application step by step.

For example, for SLP under Article 136, note down: time limit for filing, documents to be filed with petition, format requirements, limitation period, grounds for entertaining SLP, procedure for listing, notice procedure, and disposal options available to the court.

Which Topics Are Most Important in Paper 1?

In Paper I, questions on jurisdiction dominate, expect questions on Special Leave Petitions under Article 136, review petitions under Article 137, curative petitions (following Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra and Anr. [SC 2002]), writ jurisdiction under Article 32, transfer petitions, and powers under Article 142. Across the last 10 years, curative petition questions appeared at least 6-7 times with different variations.

How to Practice Application based Questions?

Create your own scenario based questions for each major topic. For example: “A party aggrieved by a High Court judgment in a criminal matter wishes to appeal to the Supreme Court. The High Court has certified the case as fit for appeal. Explain the complete procedure for filing the criminal appeal including documents required, time limits, and procedural steps.”

Then write out comprehensive answers including: (1) Identify applicable provision, (2) State time limit, (3) List documents required, (4) Explain filing procedure, (5) Mention any special requirements, (6) Cite relevant case law if applicable. Practice writing such answers within a certain time frame to simulate exam conditions. Have your training AOR supervisor or a practicing AOR review your answers and provide feedback on comprehensiveness, accuracy, and format.

Paper 2 (Drafting) Preparation Strategy

Paper 2 requires transitioning from legal knowledge to practical drafting skills. This paper separates those who’ve merely read about procedures from those who can actually prepare Supreme Court-compliant documents. Allocate approximately 30% of your preparation time to developing and perfecting your drafting skills.

Master 10-12 Core Draft Formats With Templates

Focus your drafting preparation on these essential document types that most frequently appear in the exam: Special Leave Petition (both civil and criminal), Writ Petition under Article 32, Review Petition, Curative Petition, Bail Application in Supreme Court, Transfer Petition from High Court to Supreme Court, Application for Condonation of Delay, Application for Directions, Interlocutory Application seeking interim relief.

For each document type, create a master template that includes: proper titling and case number format, party description format (petitioner vs. respondent styling), the required preliminary paragraphs, the main body structure (typically: facts in chronological order, legal grounds with constitutional/statutory citations, prayer section with specific reliefs sought), verification format, and proper spacing and numbering.

Study at least 3-4 actual Supreme Court drafts of each type to understand variations and Registry approved formats.

Where to Find Quality Drafting Samples?

Your primary source should be your AOR training supervisor’s chambers, practicing AORs maintain files of their successful petitions and can provide authentic examples showing actual formats accepted by the Supreme Court Registry.

Request permission to review (with client confidentiality respected through redaction) their SLPs, Writs, Reviews, and other common drafts. The Supreme Court’s official website provides some sample formats and guidelines for drafting, though these are limited.

Law firm websites occasionally publish sample drafts as client resources or blog content.

Legal education platforms like LawSikho offer downloadable draft templates as part of their course materials, some provide free sample downloads in their 3 day bootcamps. When collecting samples, prioritize recent drafts as formats evolve and you want current Registry compliant structures.

Paper 3 (Professional Ethics) Preparation Strategy

Paper 3 tests your ethical judgment and understanding of professional conduct standards, competencies that distinguish mere legal technicians from true professionals. While this paper receives less preparation time (approximately 15% of total study time), it requires thoughtful engagement with ethical principles rather than mere rule memorization.

Read BCI Rules Part VI Multiple Times

The Bar Council of India Rules, Part VI, Chapter II (Standards of Professional Conduct and Etiquette) forms the core of your ethics preparation, which you need to read extensively.

Reading should be for familiarization: understand the structure, what duties are covered (duty to court, duty to client, duty to opponents, duty to colleagues), and what conduct constitutes misconduct.

Next, reading should be analytical: for each rule, ask yourself why this rule exists, what problem it prevents, what competing interests it balances. For example, Rule regarding advocates not appearing in matters where they have personal interest, why? To prevent conflict of interest compromising client representation and maintain court confidence in proceedings.

Third reading should be application focused: create hypothetical scenarios where each rule would apply.

Fourth reading should be citation focused: memorize key rule numbers so you can reference them in exam answers.

Practice Analyzing Ethical Scenarios

Paper 3 questions rarely ask “State the duties of an advocate to court”, instead, they present ethical dilemmas requiring you to identify relevant rules, analyze competing interests, and recommend appropriate conduct.

To develop this analytical skill, practice with scenario-based questions. Example scenarios to practice: “An advocate discovers during trial that documents filed earlier by his client contain fraudulent information. What should the advocate do?”

Analyze this by identifying: (1) Duty to client (confidentiality), (2) Duty to court (not mislead court, prevent fraud on court), (3) Conflict resolution (duty to court is paramount), (4) Action required (inform client to correct record, if client refuses, seek permission to withdraw, inform court if fraud persists without revealing confidential information).

Understanding Duty to Court vs Duty to Client Balance

One of the most frequently tested ethical principles is the hierarchy of an advocate’s duties when they conflict. The foundational principle is: duty to court is paramount and overrides duty to client when the two conflict.

Understanding this hierarchy prevents many ethical missteps. Your duty to court includes: not making false statements, not misleading court about facts or law, not suppressing binding contrary precedents, preventing abuse of court process, maintaining court dignity and respect, and assisting court in administration of justice.

Your duty to client includes: competent representation, confidentiality of communications, acting in client’s best interest, and keeping client informed.

When these duties conflict, for example, client asks you to suppress adverse evidence or present false testimony, your duty to court prevails.

Understanding this nuanced balance and articulating it clearly in exam answers demonstrates professional maturity examiners seek.

Paper 4 (Leading Cases) Preparation Strategy

Paper 4 tests your familiarity with landmark Supreme Court jurisprudence that forms the foundation of Indian constitutional and legal framework.

The Supreme Court provides the headnotes of all the 86 cases (Volume I, Volume II and Volume III) covering majorly constitutional law, civil procedure and criminal procedure among other domains.

Strategic preparation for this paper involves selective deep reading rather than attempting comprehensive coverage of all cases equally.

Creating Case Briefs for Quick Revision

The solution is creating concise case briefs that capture essential information for exam purposes.

For each prescribed case, prepare a brief following this format:

- Case name and citation

- Key facts (2-3 sentences)

- Legal issues (1-2 sentences)

- Court’s holding (2-3 sentences)

- Significance (2-3 sentences)

- Related cases

Creating such briefs for all cases, each occupying 1-1.5 pages, gives you a comprehensive revision document of approximately 100-120 pages that you can review multiple times before the exam.

Frequently Asked Cases in Paper IV

Paper IV clearly favors certain judgments for repeated questioning.His Holiness Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalavaru v. State of Kerala [SC 1973] (basic structure), Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [SC 1978] (Article 21 expansion), Rupa Ashok Hurra v. Ashok Hurra and Anr. [SC 2002] (curative petitions), Shreya Singhal v. Union of India [SC 2015] (free speech and Section 66A IT Act), Vishaka and Ors. v. State of Rajasthan and Ors. [SC 1997] (sexual harassment), and Navtej Singh Johar & Ors. v. Union of India Thr. Secretary Ministry of Law and Justice [SC 2018] (Section 377) have all appeared multiple times across different years. When analyzing past papers, note which cases haven’t been questioned recently they might appear in your exam.

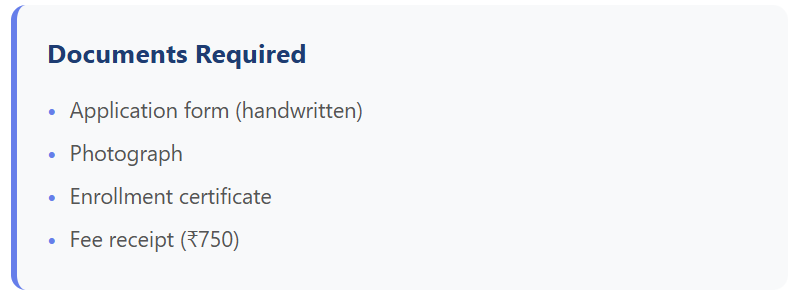

Advocate on Record Exam Application Process

Understanding the application procedure and ensuring you submit complete documentation within deadlines is crucial, procedural errors or missing documents can result in application rejection regardless of your eligibility and preparation.

Let me guide you through each step of the application process so you can navigate it smoothly when the exam notification is released.

How to Apply for the AOR Exam?

Step by Step Application Process With Required Documents

The application process begins when the Supreme Court issues the official examination notification, typically 2-3 months before the exam date.

The form is available as a PDF that you must print, complete manually in your handwriting, and submit physically.

Application Form Format and Completion Guidelines

The completed application form must be filled out carefully, and no part should be left blank.

You need to provide the following information/documents along with the application form.

1. One photograph has to be pasted at the designated place, i.e., on the topright side of the Application Form.

2. Self-attested and legible copy of the Enrolment Certificate has to be annexed to the Application Form.

Exam Fee Payment

The AOR examination fee is ₹750, payable to the UCO Bank account maintained by the Supreme Court.

Pay this fee and obtain the original payment receipt, and attach this receipt to your application form.

AOR Examination Cell Contact Details and Submission Address

Submit your completed application form with all required documents and fee receipt to the AOR Examination Cell located at Room No. 307, 3rd Floor, B-Block, Administrative Buildings Complex, Supreme Court of India, Tilak Marg, New Delhi – 110001.

The examination cell operates during Supreme Court working hours (typically 10:30 AM to 4:30 PM on weekdays).

Submit your application well before the deadline (ideally 5-7 days prior) to avoid last-minute rush and to ensure the cell has adequate time to process your application and address any deficiencies if identified.

When Will You Receive the AOR Admit Card?

Admit Card Distribution Timeline and Access Method

The Supreme Court emails admit cards to registered candidates approximately 10 days before the examination. For the June 2025 exam, admit cards were distributed on June 6, 2025. You won’t receive a physical admit card by post; instead, download the PDF from the email and take a printout.

What Happens After You Pass the Advocate on Record Exam?

Clearing the AOR exam is a significant achievement, but it’s not the final step, you must complete several post qualification formalities before you can begin practicing as an Advocate on Record.

Understanding these procedures helps you plan for the complete timeline from exam to actual Supreme Court practice commencement.

Let me walk you through the result declaration timeline and the registration procedures that follow your successful qualification.

How Long Does It Take to Declare AOR Exam Results?

8 to 10 Months Result Declaration Timeline

One of the most challenging aspects of the AOR journey is the prolonged waiting period for results.

The Supreme Court typically takes 6-7 months to declare examination results after the exam concludes. For example, if you appear for the exam in June 2025, results may be declared anywhere between December 2026 to January 2026.

This extended timeline exists because the examination is evaluated by a Board of Examiners comprising senior advocates, who review answer scripts thoroughly given the importance of the qualification.

During this waiting period, you cannot initiate any registration procedures and must continue your regular legal practice. Many candidates use this time productively to enhance their Supreme Court familiarity, network with established AORs, and prepare for the eventual transition to Supreme Court practice.

Approval and Final Registration Steps

Registration Application Submission and Documentation

Once results are declared and you’ve successfully qualified, you must submit a formal registration application to the Supreme Court seeking enrollment as an Advocate on Record.

The Supreme Court provides the registration application form at the time of result declaration or makes it available through the AOR Examination Cell.

This application requires you to provide details about your office location within the 16-kilometer radius from the Supreme Court, your clerk’s information (name, contact details, qualifications), and undertakings confirming you’ll maintain the office and employ the clerk as required.

You’ll also need to submit proof of having an office, recent passport-size photographs, and the original AOR exam certificate that you must collect in person from the Supreme Court.

Office Proof Submission Within 16 Kilometer Radius

A mandatory requirement for AOR registration is maintaining an office within 16 kilometers radius from the Supreme Court premises.

This doesn’t mean you need to own property or rent an entire office independently, many newly qualified AORs share chamber space with established AORs or rent desk space in advocates’ chambers in areas like Jor Bagh, Lodhi Estate, or other Supreme Court-proximate localities.

Your office proof can be a rental agreement showing you as tenant, a letter from an AOR offering you shared chamber space, or property ownership documents if you own space.

The key requirement is having a verifiable physical location where you can be reached, court notices can be served, and clients can meet you for Supreme Court matters.

Clerk Registration Requirement Within One Month of Registration

Supreme Court Rules mandate that every AOR must employ a registered clerk who assists with filing, court work, and liaison activities.

You must register your clerk with the Supreme Court within one month of your own AOR registration being finalized.

You can hire a clerk from the pool of experienced clerks working in the Supreme Court vicinity, many clerks work for multiple AORs simultaneously, so you don’t necessarily need an exclusive full-time clerk initially.

Registering your clerk with the Supreme Court involves submitting an application to the Registry along with the clerk’s documents. The application should include your clerk’s full name, date of birth, residential address, educational qualifications, and contact details. You’ll also need to attach photocopies of the clerk’s identity proof (Aadhaar card, voter ID, or passport), address proof, and educational certificates.

Your clerk must provide passport size photographs and give specimen signatures, which will be maintained on record by the Registry. Once the application is processed, the Registry will assign a unique registration number to your clerk.

Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association (SCAORA) Membership

After your registration as an AOR is approved by the Chamber Judge, you become eligible to join the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association (SCAORA), the official bar association representing AORs.

SCAORA membership provides access to the AOR community, networking opportunities with established practitioners, participation in bar association activities including professional development programs, and representation in matters affecting AOR interests before the Supreme Court administration.

Conclusion

The Advocate on Record examination represents one of the most challenging yet rewarding professional milestones in an Indian advocate’s career.

With approximately 0.002% of registered lawyers achieving this distinction, successfully clearing the exam positions you among an elite group with exclusive Supreme Court practice rights.

As we’ve explored throughout this guide, success in the AOR exam requires far more than legal knowledge, it demands strategic preparation, mastery of Supreme Court-specific procedures, practical drafting skills, ethical judgment, and thorough familiarity with landmark jurisprudence.

Your journey begins with ensuring eligibility through four years of practice and one year of specialized training under a senior AOR, followed by 6-12 months of intensive preparation covering all four papers strategically.

Whether you’re a junior advocate planning your long term career path or a mid career practitioner seeking to elevate your practice, the AOR qualification opens doors to India’s most significant legal forum and positions you for continued professional growth including potential senior advocate designation and judicial appointments.

Begin your preparation journey today with clear goals, structured planning, and unwavering commitment to achieving this prestigious qualification that will transform your legal career.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the AOR exam full form?

AOR stands for Advocate on Record. The full name of the examination is “Advocate on Record Examination” conducted annually by the Supreme Court of India to certify lawyers for exclusive practice rights before the apex court.

How difficult is the Advocate on Record exam to clear?

The AOR exam is considered one of India’s most challenging legal certifications with historical pass rates of only 20-30%. In recent exams, approximately 1,000-1,200 candidates appear annually, but only 200-350 successfully qualify.

Can junior advocates with 4 years practice appear for Advocate on Record exam?

Yes, advocates who have completed exactly four years of practice experience from their Bar Council enrollment date can appear for the AOR exam, provided they have also completed the mandatory one year training under a senior Advocate on Record with at least 10 years of AOR standing.

What is the Advocate on Record exam eligibility age limit?

There is no age limit, neither minimum nor maximum, for appearing in the Advocate on Record examination.

How many months preparation time is needed for the Advocate on Record exam?

Most successful candidates recommend 6-12 months of intensive preparation depending on your current Supreme Court familiarity and daily study time availability.

Can you prepare for the Advocate on Record exam without coaching?

Yes, self-preparation for the AOR exam is possible and many candidates successfully clear the exam without formal coaching.

Is the Advocate on Record exam conducted online or offline?

The AOR examination is conducted exclusively in offline mode using traditional pen and paper format in New Delhi.

Do you need to live in Delhi after becoming an AOR?

No, you don’t need to live permanently in Delhi after becoming an Advocate on Record. The Supreme Court Rules require you to maintain an office within 16 kilometers radius of the Supreme Court and employ a registered clerk, but there’s no residency mandate.

What is the difference between AOR and regular Supreme Court advocate?

The critical difference is filing rights, only Advocates on Record can sign and file pleadings, petitions, and applications in their own name at the Supreme Court. Regular advocates (including senior advocates with decades of experience) cannot file cases independently at the Supreme Court; they must engage an AOR to file on behalf of their clients.

How many attempts are allowed if you keep failing?

You are permitted a maximum of five attempts at the Advocate on Record examination throughout your career. Each appearance for the exam counts as one attempt regardless of how many papers you write or pass.

What is the salary range for Advocates on Record in India?

A new AOR typically earns between ₹12,00,000 to ₹20,00,000 annually, assuming you’re actively building your practice. Mid career AORs with 10 years of practice comfortably earn ₹30-50 lakh annually. Senior AORs with 15+ years of practice and a strong reputation regularly cross ₹1 crore in annual income. Some top practitioners earn ₹2-3 crore or more, especially those with specialized practices in constitutional law, taxation, or corporate matters.

Can advocates practicing in High Courts become AORs?

Yes, High Court practitioners can and frequently do pursue AOR qualification to expand their practice to the Supreme Court. In fact, High Court advocates often make excellent AOR candidates because they already possess strong litigation skills, courtroom experience, and client relationships that can transition to Supreme Court matters.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications