Is the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam hard? Complete difficulty analysis with candidate feedback, cut-off trends, part-wise breakdown & preparation tips.

Table of Contents

If you’re a law student or fresh graduate considering the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship examination, you’ve likely wondered just how difficult this exam really is. With only 90 positions available each year and thousands of applicants competing, the question of difficulty isn’t just academic curiosity; it’s essential for deciding whether to invest months of focused preparation into this pursuit.

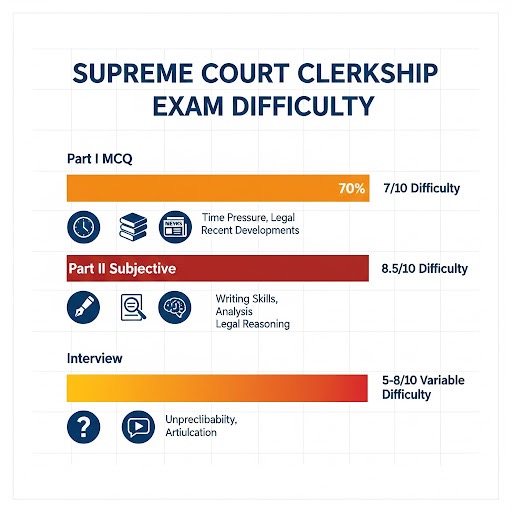

The Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam stands apart from other legal competitive examinations in India. Unlike CLAT-PG or state judiciary prelims that test primarily through MCQs, this examination combines objective questions with subjective legal writing and a personal interview with Supreme Court judges. This three-phase structure tests not just your legal knowledge, but your ability to apply law practically—a skill many law graduates struggle to demonstrate despite years of legal education.

In this comprehensive guide, I’ll give you an honest, data-backed assessment of the exam’s difficulty level. You’ll understand exactly which components are hardest, what past candidates experienced, how much preparation time different profiles need, and practical strategies to handle each challenge. By the end, you’ll have complete clarity on whether this exam suits your profile and how to approach it strategically.

What Makes the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam Different from Other Legal Exams?

Understanding the Three-Phase Selection Process

The Supreme Court conducts a rigorous three-phase selection process that evaluates candidates across different competencies. Each phase serves as an elimination round, and understanding this structure is essential for calibrating your preparation efforts appropriately.

Part I – MCQs (100 Questions)

Part I consists of 100 Multiple Choice Questions conducted online over 2.5 hours, covering Reading Comprehension, Analytical Questions on core legal subjects (Constitution, CrPC, CPC, IPC, Evidence Act, Contract Act), and Recent Developments in Law. According to the notification released by the Supreme Court scheme, each correct answer earns 1 mark with 0.25 negative marking for wrong answers, and you need a minimum 40% to qualify for Part II evaluation.

Part II – Subjective Written Test (300 Marks)

Part II is a 3.5-hour examination (including 30 minutes reading time) of 300 marks that truly separates serious candidates from the rest. Questions appear on a computer screen, but you write answers in pen-and-paper mode. The three question types test distinctly different skills: preparing a case brief/synopsis (maximum 750 words), drafting a legal research memo (500-750 words), and answering an analytical question (350-500 words).

The Drishti Judiciary examination guide explains that evaluation criteria include identification of relevant facts, recognition of legal issues, comprehensive analysis of impugned decisions, understanding of ratio decidendi, and ability to condense information logically. You need minimum 50% marks in Part II to qualify; higher than Part I’s threshold, reflecting the importance placed on writing skills.

Part III – Interview with the Supreme Court Judges

After clearing both written papers, approximately three times the number of vacancies are called for interview; so roughly 270 candidates for 90 positions. The interview assesses your legal acumen, articulation ability, and overall suitability for working directly with a Supreme Court Judge. Candidates who qualify are asked to submit a preference list of Judges’ offices where they wish to work.

The interview experience varies dramatically based on panel composition. As former Law Clerk Prerna Deep explained in her webinar, it could range from a straightforward conversation about your motivation and background to intense technical questioning where you’re asked to give your opinion on a legal crisis on the spot. This unpredictability makes specific interview preparation challenging but emphasizes the importance of having genuine, deep legal knowledge rather than surface-level familiarity.

How it differs from other law exams

Application-Based Questions vs Rote Learning

The fundamental difference between this examination and typical law school exams is the emphasis on application over recall. You won’t score well by memorising section numbers or reproducing textbook definitions. Questions test whether you can apply legal provisions to factual scenarios: identifying which principle applies and why, rather than simply stating what the law says.

You don’t really need coaching or specialized books for this exam. The essential resources are bare acts read thoroughly and complete Supreme Court judgments; not summaries from coaching materials. This approach rewards candidates who developed genuine legal reasoning skills during law school through moot courts, quality internships, and thoughtful engagement with cases rather than those who relied on rote memorization to clear examinations.

Emphasis on Recent Supreme Court Judgments and Legal Developments

One section that consistently surprises unprepared candidates is “Recent Developments in Law,” which now comprises approximately 15-20 questions out of 100. This section gained significant prominence from 2023 onwards, replacing the earlier General Aptitude and Awareness section that existed before 2023.

You simply cannot prepare this section from textbooks or coaching materials; it requires consistent engagement with Supreme Court decisions throughout your preparation period. Constitutional bench judgments and larger bench decisions deserve priority attention. A candidate who stopped following legal developments even two months before the exam might find themselves unprepared for questions that could determine their selection outcome.

How hard is the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam?

Competition Data: Applicants vs. Available Seats

Number of Applicants vs Selection Ratios

For the 2024-25 term, the Supreme Court announced 90 vacancies for Law Clerk positions. While exact application numbers aren’t officially published, estimates from legal forums suggest thousands of law graduates apply each year. What makes this competition distinctive is the quality of applicants—unlike some government exams where casual attempts inflate numbers, SC Clerkship attracts serious legal aspirants including final-year NLU students, LLM candidates, and practicing advocates, all understanding the career value of apex court exposure.

Cut-off Trends Over the Years (2018-2024)

The minimum qualifying thresholds are fixed at 40% for Part I and 50% for Part II, but actual competitive cut-offs run significantly higher. Based on forum discussions and candidate experiences, scoring 60+ in Part I and 150+ in Part II typically puts candidates in competitive territory for interview calls. The trend shows progressive increase in difficulty, with candidates noting that what was considered a good score in 2021 may not suffice in 2024.

What Past Candidates Say About the Difficulty Level

Comparing 2023 vs 2024 Difficulty Levels

The 2024 examination marked a notable difficulty spike compared to previous years. Discussions on prominent students and aspirants platforms reveal candid reactions: one candidate wrote that scoring 80 out of 100 was achievable in earlier years, but in 2024 “even 50/100 is difficult” due to “ambiguous options and questions based on latest judgements.” Another noted the paper was “super tough and lengthy,” with many scoring around 30 marks despite preparation.

According to Legally Flawless analysis, key changes included reduced examination time (2.5 hours compared to 3 hours previously), heavier emphasis on recent constitutional developments, and Part II questions that differed significantly from sample papers provided by the Supreme Court itself. Candidates noted an overwhelming focus on Constitution questions: one forum post asked frustratedly, “Why was there so much constitution?” This upward difficulty trend suggests future examinations will likely continue this pattern.

Real Experiences from Recent Exam Attempts

Understanding what the clerkship actually entails; and how successful candidates prepared for it offers valuable perspective beyond official guidelines. Recent testimonials from those who’ve navigated both the selection process and the role itself reveal patterns that can inform your preparation strategy.

Sarthak Karol’s account in Bar and Bench provides insight into what the clerkship demands. He describes it as “one of the most challenging and intellectually stimulating experiences” of his life, noting that law clerks must come to terms with extremely high workloads, limited time for personal life, and the expectation to work “twice as hard” to fill gaps in research that the Bar sometimes leaves. His experience working on 41 days of the Ayodhya proceedings illustrates the intensity of the role.

The Manupatra webinar with Prerna Deep offered a memorable perspective: “one year of clerkship is equal to 5 years of litigation, if you do it right.” She emphasised that the exam rewards application over memorisation, and that candidates who read complete judgments (not summaries) and develop genuine research skills have significant advantages. Her honest assessment that “you don’t really need coaching” reassures candidates that systematic self-preparation can succeed.

Difficulty Comparison with Other Law Competitive Exams

SC Clerkship vs CLAT-PG

If you’ve prepared for CLAT-PG, you have a meaningful head start. The legal reasoning sections overlap considerably, and your familiarity with application-based questions translates well. However, SC Clerkship places heavier emphasis on procedural laws; particularly CPC, which CLAT-PG doesn’t cover at all.

The significant difference lies in Part II. CLAT-PG tests only through MCQs, while SC Clerkship requires you to draft case briefs and legal memos under time pressure—skills that require separate practice. Additionally, the “Recent Developments” emphasis is stronger in SC Clerkship, demanding consistent judgment reading rather than the current affairs approach sufficient for CLAT-PG.

SC Clerkship vs State Judiciary Prelims

State judiciary preliminary examinations cover similar substantive areas but typically feature more provision-based, direct recall questions. SC Clerkship questions tend toward analytical application; you’re tested on whether you can apply legal principles to novel factual scenarios rather than reproducing section contents. However, if you’ve been preparing for judiciary exams, the subject coverage will feel familiar.

The key differentiators are again Part II (state judiciary mains have descriptive papers, but the specific skills of brief preparation and legal memo writing are unique to SC Clerkship) and the Recent Developments section. Judiciary aspirants often focus on procedural law provisions more than recent judgments, requiring adjustment in preparation approach for SC Clerkship’s emphasis on constitutional bench decisions and recent legal developments.

Which Part of the Exam is the Hardest?

Part I MCQ – Where Most Candidates Struggle

Despite its objective format, Part I is where most eliminations occur. The combination of negative marking, time pressure, and application-based questions catches many candidates unprepared.

Subject-Wise Question Distribution and Weightage

Based on previous year analysis, question distribution has evolved significantly over the years. The Constitution of India consistently receives high weightage with 15-20 questions. CPC and CrPC together account for approximately 20-21 questions. IPC and Evidence Act contribute roughly 20 questions combined. Contract Law gained prominence from 2023 onwards with 10-12 questions.

Notably, English Comprehension reduced from 30 questions (2018-2021) to approximately 15 questions (2023-2024), while Recent Developments in Law increased from negligible presence to 15-20 questions. This shift means you cannot rely on general English aptitude to carry you through; strong legal fundamentals across all specified subjects are now essential for clearing Part I.

The Challenge of Recent Developments in Law Section

This section catches many candidates off-guard because you cannot prepare it through textbooks or coaching materials. It requires consistent reading of Supreme Court judgments throughout your preparation period: priority should go to recent constitutional bench decisions and larger bench judgments as these are most likely to appear. Someone who stopped following legal developments even two months before the exam might find themselves unprepared for a section now worth 15-20% of Part I marks.

Why Part II Subjective Paper is the Real Differentiator

Many candidates clear Part I but stumble on Part II. The 50% qualifying threshold is higher, and the subjective nature means there’s no partial credit for “almost correct” answers.

Brief Preparation Skills Most Lack

Question 1 requires you to prepare a synopsis of a case file: a Special Leave Petition, Appeal, or Writ Petition in maximum 750 words. You must identify relevant facts, recognise legal issues, analyze the impugned decision’s ratio, and condense everything logically and clearly. These are skills typically developed through quality internships or litigation practice, not classroom learning. If you’ve never actually read and summarized a case file during internships, this format will feel unfamiliar and intimidating.

Legal Memo Writing Under Time Pressure

Question 2 asks you to draft a reasoned legal memo based on a factual dispute with relevant statutes and precedents provided; some relevant, some deliberately irrelevant to test your filtering ability. The evaluation criteria include use of appropriate legal sources, application of legal language, clear exposition and analysis of law, application of law to facts, and structural clarity of opinion. You must produce 500-750 words of quality legal writing under exam pressure, a skill that requires dedicated practice beyond subject knowledge.

What Makes the Interview Unpredictable

How Panel Composition Affects Question Types

The interview experience varies dramatically based on which panel you face. Some panels focus on motivation questions (“Why clerkship?”), your background, and general legal interests. Others dive into technical legal questions, ask your opinion on current legal controversies, or even give you material to read and analyse on the spot. This variability makes specific preparation difficult; you cannot predict which approach you’ll encounter.

From Simple to Intensely Technical: What to Expect

Interviews can range from an “actual cakewalk” to demanding technical assessments. What remains constant is that you should be able to articulate your genuine interest in the clerkship, demonstrate current awareness of significant legal developments, display comfort with legal reasoning, and think on your feet when posed unexpected questions. Surface-level preparation won’t suffice if you encounter a technically demanding panel.

How Much Time Do You Need to Prepare for This Exam?

Preparation Timelines Based on your Starting Point

Your required preparation time depends significantly on your existing knowledge base, exam experience, and current engagement with legal developments.

If You’re Already Preparing for CLAT-PG or Judiciary

The syllabus overlap works significantly in your favor. You’ll primarily need to add CPC if coming from CLAT-PG preparation, intensify focus on recent developments in law and constitutional bench judgments, and develop Part II writing skills through dedicated practice.

If You’re Starting Fresh

Candidates starting from scratch need substantially more time for comprehensive coverage. You’ll need to cover the complete syllabus across Constitution, IPC, CrPC, CPC, Evidence Act, and Contract Act, build application skills through extensive practice with previous year papers, develop Part II writing skills through consistent brief and memo practice, and create a daily habit of following recent Supreme Court judgments.

Quick Revision

For candidates who studied these subjects thoroughly during law school and have strong fundamentals but haven’t actively revised recently, a structured quick revision approach works. Focus 60% time on practice (previous year papers, Part II writing exercises) and 40% on targeted revision of high-weightage topics and recent developments.

Creating a Subject-Wise Preparation Strategy

High-Weightage Topics to Prioritize

Based on previous year analysis, prioritise Constitution of India (especially Fundamental Rights, Directive Principles, judicial review, and jurisdictions), CPC and CrPC procedural aspects, IPC general exceptions and specific offenses, Evidence Act on admissibility, relevance, and burden of proof, and Contract Act essentials. Recent Developments in Law requires ongoing attention throughout preparation; you cannot cram this section at the end since it tests current awareness rather than static knowledge.

Balancing Bare Acts with Judgment Reading

Read bare acts as your primary resource for understanding provisions, but supplement with landmark judgments to understand application. For each major provision, try to find at least one significant Supreme Court judgment that applied it; this builds the application mindset the exam rewards. Allocate approximately 60% time to bare acts and 40% to judgment reading. For Recent Developments, constitutional bench judgments from the past year deserve priority attention, supplemented by significant division bench decisions on important legal questions.

Practical Strategies to Handle the Difficulty Level

Mastering Previous Year Papers

Previous year papers are your most valuable preparation resource; they reveal not just what topics are tested, but how questions are framed and what level of application is expected.

Subject-Wise Question Trends (2018-2024)

Our recent article on detailed analysis reveals significant evolution in question patterns. English Comprehension dropped from 30 questions (2018-2021) to 15 questions (2023-2024). The Constitution of India has remained consistent at 15-20 questions throughout. CPC questions reduced from 20 (2018-2021) to 10-11 (2023-2024). Contract Law emerged as significant from 2023 onwards with 10-12 questions. Recent Developments increased from negligible presence pre-2023 to 15-20 questions now.

Understanding these trends helps you allocate preparation time effectively. The shift toward more application-based law questions and reduced English comprehension questions means you cannot compensate for weak legal fundamentals with strong general aptitude. Focus your energy on substantive legal subjects and recent developments rather than spending disproportionate time on English grammar and vocabulary.

How to Practice Under Exam Conditions

Solve at least 3-5 previous year papers under timed conditions (2.5 hours, no breaks, no reference materials) before the actual exam. Track your time allocation per section and identify where you’re losing time. Analyze mistakes categorically: conceptual errors need subject revision, careless mistakes need attention practice, and time management issues need strategy adjustment. This self-diagnosis enables targeted improvement rather than generic “study more” approaches.

Building Legal Awareness for Recent Developments

Constitutional Bench Judgments to Focus On

For candidates appearing in 2025, you can focus on recent Constitution bench judgments such as In re: Section 6A Citizenship Act (Assam NRC case) [2024 INSC 789], Aligarh Muslim University through its Registrar Mr. Faizan Mustafa vs. Naresh Agarwal [Civil Appeal No. 2286 of 2006] on AMU Minority Status, and Central Organisation For Railway Electrification v ECL-SPIC-SMO-MCML (JV) [2024 INSC 857] on unilateral appointment of the Arbitrator, etc. which are readily available on multiple websites.

Resources for Staying Updated

Build a daily reading habit using reputed legal news sources: Live Law, Bar and Bench, SCC Online, and Supreme Court Observer provide reliable coverage. Set up email alerts or follow dedicated Telegram channels for Supreme Court judgments. Spending 15-20 minutes daily on legal updates is more effective than cramming before the exam. Create brief notes of significant judgments: ratio, key facts, and constitutional provisions involved, for quick revision.

Developing Part II Writing Skills

Brief Preparation Practice Methods

Practice reading actual case files during internships and preparing concise summaries following the examination format. Focus on developing skills in fact identification (what happened and when?), legal issue recognition (what question of law arises?), impugned decision analysis (what did the lower court/tribunal hold and why?), and grounds before the Supreme Court (why should SC interfere?). Practice condensing complex files into 750-word summaries repeatedly until this becomes natural.

Request seniors or mentors to review your practice briefs and provide feedback on clarity, structure, and completeness. The ability to distinguish relevant from irrelevant facts, identify the core legal issue among peripheral matters, and present everything in logical sequence within word limits requires deliberate practice as it won’t develop automatically from subject knowledge alone.

Templates of Legal Memo Structure

A legal research memo follows a specific structure: Issue Statement (clear articulation of the legal question), Applicable Legal Framework (relevant statutes, rules, and precedents), Analysis (applying law to the specific facts, addressing arguments for and against), and Conclusion (clear recommendation or opinion). Practice this format with hypothetical scenarios until the structure becomes instinctive. Focus on clarity, logical flow, and precise legal language rather than impressive vocabulary or complex sentence construction.

Career Benefits of Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship

Supreme Court Networking and Future Opportunities

The career value of Supreme Court Clerkship extends far beyond the one-year assignment. Working directly with a Supreme Court Judge provides unparalleled exposure to apex court functioning, judicial decision-making processes, and interactions with the country’s finest legal minds. Sarthak Karol’s Bar and Bench article describes witnessing the Ayodhya proceedings; learning “courtroom courtesies, spontaneity, flair, emphasis, and strategic pauses” from the Bar’s brightest luminaries.

The networking benefits are substantial: you build relationships with your assigned Judge, senior advocates who appear regularly, fellow clerks who often pursue distinguished legal careers, and the broader Supreme Court community. These connections accelerate career growth whether you pursue litigation, academia, or judicial services. For those considering foreign LLM programs, many prestigious universities explicitly gives preference to candidates with judicial clerkship experience, making this a valuable credential for higher education applications abroad.

Salary of a Supreme Court Judicial Clerk

The current consolidated monthly remuneration is ₹80,000. This is competitive for an entry-level legal position, especially considering that accommodation assistance may be available and the role provides library access, research database subscriptions, and other facilities. Beyond monetary compensation, the experience value; Supreme Court exposure, judicial mentorship, and credential building typically exceeds what the stipend alone represents, justifying the popular statement that “one year of clerkship equals five years of litigation.”

Conclusion

So, is the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam hard? The honest answer is: it depends on your starting point and preparation approach. For candidates with CLAT-PG or judiciary examination backgrounds, the syllabus overlap makes it manageable with 6-8 weeks of focused additional preparation. For those starting fresh, the breadth of subjects, emphasis on application-based questions, Part II writing requirements, and recent developments section create genuine challenges requiring 3-6 months of systematic preparation.

What’s objectively clear is that the exam has become progressively harder in recent years. The 2024 examination saw candidates who previously scored 80+ struggling to cross 50 marks. Competition is real: you’re facing serious aspirants from top law schools for limited positions. But the exam rewards genuine legal engagement over coaching-dependent preparation, and thousands have cleared it without expensive courses. Your success depends on systematic preparation prioritizing high-weightage subjects, consistent engagement with recent Supreme Court judgments, deliberate practice of Part II writing skills, and honest assessment of your starting point to set realistic timelines. The challenge is significant, but worth taking if working at the apex court aligns with your career aspirations.

For more insights on this topic, visit our iPleaders blog.

Frequently Asked Questions on the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam

Is the Supreme Court Judicial Clerkship Exam harder than CLAT-PG?

SC Clerkship has significant overlap with CLAT-PG in legal reasoning, but adds CPC coverage entirely, emphasizes recent Supreme Court judgments more heavily, and includes Part II subjective paper testing professional writing skills that CLAT-PG doesn’t assess.

What is the passing percentage for the SC Judicial Clerkship Exam?

The minimum qualifying marks are 40% in Part I (40 out of 100) and 50% in Part II (150 out of 300). However, competitive selection requires significantly higher scores; typically 60+ in Part I and 150+ in Part II for interview consideration.

Can I clear the exam without coaching?

Absolutely. Former clerks confirm you don’t need coaching; the essential resources are bare acts read thoroughly, complete Supreme Court judgments, and previous year papers for practice. Many successful candidates prepared independently using freely available resources.

How many questions should I attempt in Part I to qualify?

With 0.25 negative marking, attempt questions you’re reasonably confident about. A rough strategy: attempting 80-90 questions with 70-75% accuracy yields approximately 55-65 marks after deduction; comfortably above the 40% threshold.

Is the interview very hard for non-NLU candidates?

Your law school doesn’t determine interview performance. Panels assess legal acumen, articulation, and suitability; qualities developed through genuine engagement with law, not institutional affiliation. Non-NLU candidates regularly succeed through strong preparation.

What happens if I clear Part I but fail Part II?

If you score below 50% in Part II, you’re eliminated from that year’s selection process. There’s no partial advancement, you would need to reapply and attempt both papers in subsequent years.

Can final year students appear for this exam?

Yes, candidates in the fifth year of five-year integrated law courses or third year of three-year LLB courses are eligible. However, you must submit proof of obtaining your law degree before starting the assignment as Law Clerk.

Is knowledge of computer research tools tested in the SC Judicial Clerkship Exam?

The eligibility criteria mention proficiency in legal research tools like e-SCR, Manupatra, SCC Online, LexisNexis, and Westlaw. While Part I may not directly test software operation, research ability may be assessed during interviews.

What is the stipend after selection and is it worth it?

The current consolidated monthly remuneration is ₹80,000. Beyond monetary compensation, the experience value; Supreme Court exposure, judicial mentorship, networking, and credential building typically exceeds what the stipend represents, making it worthwhile for career-focused candidates.

Does poor handwriting affect Part II marks?

Part II is written in pen-and-paper mode, and legibility absolutely matters; evaluators must read your answers. While there’s no formal “handwriting marks,” illegible answers may lose credit if evaluators cannot decipher your points. Practice writing legibly at moderate speed.

Can I prepare for the SC Judicial Clerkship Exam and Judiciary exams together?

The syllabus overlap makes combined preparation feasible and efficient. Constitutional law, criminal law, civil procedure, and evidence law are common to both. However, SC Clerkship emphasizes application-based questions and recent judgments more heavily than provision-based judiciary papers.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications