Who exactly is an Advocate-on-Record (AOR) in the Supreme Court? This guide explains the full meaning, role, and significance of AORs, how they differ from other advocates, what exclusive rights they hold, and why qualifying as an AOR marks a major milestone in a lawyer’s Supreme Court practice.

Table of Contents

“You cannot file that petition yourself. You need an AOR.”

If you’ve ever tried to take a case to the Supreme Court of India, you’ve heard these words.

But what exactly is an Advocate on Record?

More importantly, what does their daily life actually look like beyond the prestigious title and the courtroom drama you see on news channels?

If you’ve ever wondered what it’s really like to practice before India’s highest court, not the glamorous version you see in movies, but the actual daily reality, you’re in the right place.

This guide goes beyond the procedural basics you’ll find elsewhere. We’re diving into what the actual workday of AOR looks like.

You’ll discover the essential skills that separate successful AORs from struggling ones, and they’re not all about legal knowledge.

We’ll break down the income reality at every career stage, examine the financial realities of running a chamber with rent, junior salaries, and operating costs before you earn your first rupee.

Whether you’re a law student considering the AOR path or a practicing lawyer preparing for the AOR exam, this comprehensive guide offers the insider perspective you won’t find in textbooks or official Supreme Court materials.

Ready to step inside the life of an Advocate on Record?

Let’s begin with understanding what an AOR is.

What Is an Advocate on Record in the Supreme Court?

Defining the Advocate on Record Role

An Advocate on Record is authorized under Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, to file cases, represent clients, and appear before the Supreme Court.

What sets AORs apart from regular advocates is their dual role: they can both file documents (which only they can do) and argue cases. Even senior advocates designated by the Supreme Court cannot file a single document without instructing an AOR to do so on their behalf.

Think of an AOR as the gatekeeper to Supreme Court justice. Out of over 15 lakh+ lawyers in India, only about 3789 hold this prestigious designation.

To become one, you need at least four years of practice, one year of intensive training under an existing AOR, and then you must pass a rigorous four paper examination conducted by the Supreme Court itself.

After passing, you’re assigned a unique AOR code, must maintain a registered office within 16 kilometers of the Supreme Court, and employ a registered clerk. The journey doesn’t end with qualification.

As an AOR, you become personally liable for all fees and filings in cases you handle. The Supreme Court holds you directly accountable for professional conduct, proper drafting, timely appearances, and maintaining the highest ethical standards. This responsibility is both a burden and a badge of honor that distinguishes AORs from other legal professionals.

Importance of AOR in the Supreme Court

The AOR system exists for a crucial reason: the Supreme Court needs advocates who are thoroughly versed in its unique procedures, rules, and standards.

Judges elevated from various High Courts across India may not initially be familiar with Supreme Court practice, and they rely on experienced AORs to assist them. Every matter before the apex court involves voluminous records, complex constitutional questions, and documents often in vernacular languages.

AORs bridge the gap between clients, advocates, and the Court itself, ensuring that cases are properly presented, procedural requirements are met, and the Court’s time is used efficiently.

Without AORs maintaining these standards, the Supreme Court’s functioning would face significant challenges. They’re not just lawyers filing cases; they’re officers of the Court responsible for upholding the dignity and efficiency of India’s judicial apex. This is why the Supreme Court carefully regulates who becomes an AOR and holds them to stringent professional standards.

What Are the Core Responsibilities of an Advocate on Record?

Exclusive Privileges of AOR in Supreme Court Practice

Let me tell you about the extraordinary power an AOR holds in India’s legal system. Only an Advocate on Record can file a vakalatnama, the document that authorizes a lawyer to represent you in the Supreme Court. This means if you have a case reaching the apex court, you absolutely must engage an AOR. No matter how experienced your lawyer is, no matter if they’re a designated Senior Advocate with decades of practice, they cannot file a single petition, application, or document in the Supreme Court without an AOR’s involvement.

Beyond filing, AORs have the privilege of appearing and arguing matters themselves, though many brief Senior Advocates for oral arguments while handling the procedural aspects.

Daily Duties: Filing, Drafting, and Court Appearances

When you become an AOR, your primary duty is ensuring that every document you file meets Supreme Court standards. This means drafting petitions, applications, affidavits, and written submissions with meticulous attention to the Court’s format requirements, font specifications, paper quality, binding standards, and pagination rules.

A petition that doesn’t comply with these technical requirements will be rejected by the registry, wasting everyone’s time and potentially missing crucial limitation deadlines.

I’ve seen AORs spend hours perfecting a single Special Leave Petition because they know the difference between a well drafted petition and a mediocre one can determine whether the Court even agrees to hear your case.

The drafting work is intellectually demanding. You’re not just stating facts; you’re identifying the substantial question of law that justifies Supreme Court intervention, synthesizing judgments from different High Courts to show conflict or legal inconsistency, framing constitutional questions precisely, and presenting your client’s case in a way that resonates with judges dealing with hundreds of matters daily.

Court appearances form another critical duty. Supreme Court matters can be listed for “mentioning” (brief submission to request early hearing), regular hearings, final arguments, or miscellaneous applications. On heavy listing days, an AOR might have eight or ten matters spread across different benches sitting simultaneously. You’re constantly moving between courtrooms, making brief submissions, noting down Court orders, and coordinating with Senior Advocates you’ve briefed for specific matters.

The administrative duties are equally important. You must maintain detailed books of account showing money received from and paid on behalf of each client. Before taxation of bills, you must file certificates showing fees paid to you or agreed upon by your client.

You’re responsible for filing appearance slips for every matter you appear in, maintaining your AOR records with the registry, ensuring your clerk’s registration remains current, and keeping your office address updated.

Managing Client Relationships and Case Coordination

One of the most challenging aspects of AOR practice is managing client expectations. Your clients often come to you after losing in the High Court, emotionally invested in their cases and convinced that the Supreme Court will vindicate them. You must explain that the Supreme Court is not a regular court of appeal; it intervenes only when there’s a substantial question of law, jurisdictional error, or manifest injustice.

Many clients struggle to understand why the apex court might not even admit their case for hearing. This requires patient, clear communication about Supreme Court practice realities while maintaining their trust and confidence.

I’ve learned that transparency from the very first meeting prevents misunderstandings later. You need to explain your fee structure clearly, what you charge for filing, what you charge for appearances, whether Senior Advocate fees are separate, and what additional costs might arise (court fees, typing charges, printing costs, clerk fees).

You should also give them realistic timelines. Supreme Court cases don’t resolve quickly; matters can take months or even years depending on the backlog, bench composition, and case complexity. Setting accurate expectations prevents the frustrated phone calls asking, “Why hasn’t my case been heard yet?” three weeks after filing.

Client coordination involves much more than legal work.

For many clients, you become their guide to navigating not just the Supreme Court but the entire legal system. This relationship management requires empathy, patience, and excellent communication skills, qualities that the AOR examination doesn’t test but that determine whether clients stay with you and refer others to your practice.

Technology has added another dimension to client coordination. Clients now expect immediate responses to WhatsApp messages, quick turnaround on queries sent via email, and regular updates even when there’s no significant progress. You’re managing client communication across multiple channels while trying to focus on substantive legal work.

The successful AORs I know set clear boundaries, perhaps responding to nonurgent messages only during specific hours, or having their juniors handle routine queries while they focus on court appearances and drafting. Finding this balance between accessibility and protecting your time for focused work is crucial for sustainable practice.

A Day in the Life of an AOR

How Does a Typical Workday Begin for an AOR?

Morning Chamber Routine: Preparation for Supreme Court Hearings

The alarm goes off at 6:30 AM on most workdays.

By 7:30 AM, I’m at my chamber near the Supreme Court complex, well before the rest of Delhi’s legal district fully wakes up. These early morning hours are sacred, they’re when I can think clearly without interruptions, review the day’s matters, and ensure everything is in order before the chaos of court begins. I start by checking the Supreme Court website for the daily cause list.

The first thing I do is make a list of my matters listed today across different benches. Let me give you a real example from last Tuesday: I had three matters in Court 2 before the CJI’s bench, two matters in Court 5 before Justice Surya Kant’s bench, and one urgent mentioning I needed to make in another Court.

I color code them by urgency: red for matters likely to be called early, yellow for regular listings, and green for matters that typically get called after lunch. This system has saved me countless times from missing a crucial hearing because I was in another courtroom.

Next, I brief my junior associates. I have two juniors working with me currently, one with three years of experience who handles most drafting work, and a fresh law graduate who assists with research and administrative tasks.

In the morning huddle, I assign them their tasks for the day: my senior junior will attend matters that are straightforward and I trust him to make basic submissions if they’re called while I’m in another Court. My junior will handle filing tasks, collect signed orders from the registry, and prepare notes for tomorrow’s hearings. Clear delegation is essential because I physically cannot be in three courtrooms simultaneously.

The next hour is spent reviewing case files for today’s matters. For each case, I review my notes from the last hearing, check if any documents need to be filed, prepare the points I need to emphasize, and anticipate questions the bench might ask.

If I’ve briefed a Senior Advocate for any matter, I coordinate with them, sending a quick message confirming the matter is listed and at what serial number.

For the mentioning, I prepare a brief one minute submission explaining why urgent hearing is necessary. Every minute of this preparation matters because Supreme Court benches move quickly, and you must be ready to make your submissions concisely the moment your matter is called.

By 9:30 AM, I’m reviewing physical files one last time, ensuring all necessary documents are in my bag, my notebook has blank pages for noting orders, and I have copies of key judgments I might need to cite. I also check messages from clients, sometimes they have last minute information or questions that need addressing before court. My clerk confirms that all appearance slips are ready to be filed.

The chamber routine might seem mundane, but this systematic preparation is what allows me to handle multiple matters efficiently once the court begins. Senior AORs have told me that mastering the morning routine is half the battle; show up unprepared and you’ll spend your entire day playing catch up.

Around 10:00 AM, I head to the courtroom. I like to be there 15-20 minutes before the bench assembles at 10:30 AM. This gives me time to check the physical cause list board, mark my matters, coordinate with other AORs if there are common matters or conflicting schedules, brief Senior Advocates if they’ve arrived, and mentally shift from preparation mode to court mode. These minutes of settling in make a significant difference in my composure and readiness when the judges enter and proceedings begin.

Court Session: Managing Multiple Matters Across Different Benches

Once the Supreme Court bench assembles at 10:30 AM, the atmosphere shifts completely.

You’re now in the highest court of the land, and everything moves fast. The Court typically hears anywhere from 50 to 100+ matters in a single day, depending on the bench and the board (admission board, regular hearing board, or miscellaneous board).

Your matter might be serial number 47, meaning 46 matters are ahead of you.

But here’s the catch: many of those matters will be passed over, adjourned, or disposed of in minutes, so your matter could be called anytime.

You can’t leave the courtroom, or you risk missing your turn. I keep my phone on silent but visible, watching for messages from my junior in another Court telling me if that matter has been called. This juggling act between multiple courtrooms is one of the most stressful aspects of Supreme Court practice.

Sometimes I’m making submissions in one Court when my phone vibrates with a message that my matter in another Court just got called. I have to quickly wrap up, excuse myself, and rush to the other Court, hoping the matter hasn’t been passed over. On days when this happens repeatedly, I easily walk 10,000 steps just moving between courtrooms in the Supreme Court complex.

Post Court Work: Drafting Work, Client Consultations and Case Preparation and Legal Research

By the time the court rises around 4:00 or 4:30 PM, I’m mentally exhausted but the workday is far from over. I head back to my chamber and spend the next 30-45 minutes completing administrative tasks: filing appearance slips for all matters I appeared in, noting down detailed records of what happened in each matter, updating my case management system, and sending brief updates to clients whose matters were heard today.

This administrative work is tedious but absolutely essential; if I don’t do it immediately while details are fresh, I’ll forget crucial information that clients will ask about later.

From around 5:00 to 6:30 PM, I hold client consultations. These are typically scheduled in advance, people who want to discuss filing new cases, existing clients who need detailed case updates beyond a quick phone call, or potential clients evaluating whether to engage my services.

The evening hours from 7:00 PM onwards are when I do my best drafting work.

The phone stops ringing, clients stop messaging, and I can finally focus on the intellectual work that drew me to this profession.

Tonight, I’m drafting a Special Leave Petition challenging a High Court order in a service matter. This requires carefully reading the impugned judgment, identifying the errors of law, researching Supreme Court precedents that support my client’s position, and crafting a narrative that makes the judges want to hear this case.

Good drafting at the Supreme Court level is an art form; you’re not just presenting facts and law, you’re telling a story that demonstrates why the High Court got it wrong and why correcting that error matters.

I’ll typically spend 3 to 4 hours on a substantial petition, often working until 10:00 or 11:00 PM when I have filing deadlines approaching.

My family has adjusted to my schedule, but I won’t pretend this doesn’t strain personal relationships; missing dinners is routine, and weekend work is common.

Some evenings are dedicated to legal research rather than drafting. Recently, I spent an entire evening researching a constitutional question about the scope of Article 21 in the context of environmental rights. I maintain a personal database of important judgments organized by topic, which I continuously update based on new Supreme Court decisions. This research infrastructure is essential but time consuming to build and maintain.

Weekends have a different rhythm but they’re rarely free. Saturday mornings, I typically catch up on correspondence I couldn’t handle during the week, detailed coordination with lawyers in other cities about cases we’re collaborating on, and administrative matters like billing and record keeping.

Saturday afternoons, I might work on longer term projects like substantial written submissions for matters coming up next month.

Sundays are theoretically off, but there’s usually some case related reading I need to do. The boundary between work and personal time is porous in this profession, and maintaining any semblance of work life balance requires conscious effort and discipline, which I’m still learning to master.

Essential Skills for Advocate on Record Success

What Core Legal Competencies Must Every Advocate on Record Master?

Supreme Court Rules and Procedural Expertise

Let me be direct: if you don’t know the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 inside and out, you will fail as an AOR. I’m not talking about casual familiarity; I mean being able to cite Order numbers, Rule numbers, and their implications in your sleep.

When a registry officer points out that your petition doesn’t comply with a particular Order, you need to immediately understand what’s wrong and how to fix it. When a bench asks whether condonation of a 500-day’ delay is even possible under the relevant limitation provision, you must know the answer instantly.

The Supreme Court Rules cover everything from the format of petitions (font size, margin width, paper quality, binding standards) to the procedure for different types of applications (interventions, impleadment, condonation of delay) to court fee calculations for various matters.

You must know which matters can be filed under Article 136 (Special Leave Petitions), which require Article 32 (Writ Petitions), when Original Suits under Article 131 are appropriate, and how Transfer Petitions differ in the Civil Procedure Code and Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023.

This isn’t theoretical knowledge; every day, you’re applying these rules to determine whether your client’s case can even be filed in the Supreme Court.

Beyond the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, you needa thorough familiarity with procedural statutes like the Civil Procedure Code and Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita, 2023, the Limitation Act 1963, and the Court Fees Act 1870. Supreme Court practice constantly

What distinguishes excellent AORs is not just knowing the rules but understanding their underlying purpose. When you understand why rules exist, you can comply with them more effectively and even make arguments about when substantial compliance should suffice despite technical deviations.

Constitutional Law Depth and Case Knowledge

Your constitutional law knowledge must be at a level beyond what law school teaches.

You need to understand not just Article 14 (equality) or Article 21 (life and personal liberty) but the entire judicial doctrine developed around these provisions.

What’s the difference between manifest arbitrariness and mere unreasonableness under Article 14? How do you establish that a statute violates the basic structure doctrine? These aren’t academic questions; they’re live issues in cases you’ll handle.

The AOR examination tests your knowledge of leading Supreme Court judgments, and rightly so. But practical AOR work requires much more. You must stay current with the Supreme Court’s latest judgments because constitutional doctrine evolves constantly.

You need to know landmark cases like Holiness Kesavananda Bharati Sripadagalavaru v. State of Kerala [ SC 1973] (basic structure doctrine), Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India [SC 1978] (Article 21 expansion), Minerva Mills Ltd. & Ors. v. Union of India & Ors.[ SC 1981] (judicial review), and dozens more, not because they’re exam staples but because you’ll cite them in almost every constitutional matter you handle.

I maintain a personal notebook where I summarize every constitutional bench decision, noting the key principles and how they modify earlier law.

Case knowledge extends beyond constitutional law. You need familiarity with leading judgments in civil law, criminal law, service law, tax law, company law, and essentially every field where Supreme Court appeals arise. When drafting a Special Leave Petition in a property dispute, you must know which Supreme Court judgments govern adverse possession, partition, specific performance, and related issues. This breadth of knowledge takes years to develop and requires continuous study even after becoming an AOR.

Drafting Precision to Supreme Court Standards

Supreme Court drafting is a specialized skill that takes years to master.

I’ve seen experienced High Court lawyers struggle because Supreme Court petitions follow completely different conventions.

- The cause title must be formatted precisely with petitioner and respondent names, case numbers from lower courts, and proper court designation.

- Your index of the paper book must match the actual documents filed with exact page number correspondence.

- The list of dates must be chronological, accurate, and include only genuinely relevant events, not every minor procedural step from the trial court.

- The statement of facts must be concise, objective, and focused on facts relevant to the legal questions you’re raising, not a narrative retelling of everything that happened.

- Your grounds section must clearly state the substantial questions of law without simply repeating facts.

- The synopsis must distill your case that judges can read in five minutes and understand your core contentions.

Every element serves a specific purpose in helping the Court efficiently process your case. Poor drafting doesn’t just annoy judges; it can result in your petition being dismissed without a hearing simply because the Court cannot discern what legal question you’re raising or why it merits Supreme Court attention.

Which Court Practice Skills Distinguish a Successful AOR?

Oral Advocacy Excellence: Presenting Before the Highest Bench

Standing before a Supreme Court bench and presenting your arguments is fundamentally different from advocacy in any other court. The judges have read your petition before the hearing.

They’ve already identified potential weaknesses in your arguments and they’ll interrogate those weaknesses immediately. You might start presenting your facts when a judge interrupts: “Mr. Counsel, we’ve read your petition. What is your answer to the respondent’s contention that this Court has already settled this question in judgment X?” You need to respond instantly, precisely, and persuasively.

Supreme Court oral advocacy rewards clarity, brevity, and directness. You have limited time, sometimes just 5-10 minutes depending on the board and the bench’s disposition. You cannot waste time on lengthy preambles or dramatic flourishes.

I’ve learned to start with my strongest point immediately: “My Lords, this petition raises a substantial question of law regarding the interpretation of Section 17 of the XYZ Act, where there’s a clear conflict between the judgment of the Delhi High Court and the Bombay High Court.”

This immediately tells the bench why your case deserves their attention. Then you make your 2-3 core submissions, cite 2-3 binding precedents, and sit down. Overarguing is a common mistake; knowing when to stop is as important as knowing what to say.

Quick Thinking and Responding to Judicial Questioning

The real test of advocacy skill is how you handle judicial questioning.

Supreme Court judges ask penetrating questions that go straight to the heart of your case. Sometimes they’re genuinely seeking clarification; other times they’re testing whether you’ve thought through the implications of your arguments.

When the Chief Justice asks, “What about limitation, Mr. Counsel? Your cause of action arose in 2019, you filed in 2024, that’s five years,” you cannot fumble or ask for time to check.

You must immediately explain why the limitation is satisfied: “My Lords, the limitation period doesn’t begin until the aggrieved party has knowledge of the injury, and in this case, the appellant only discovered the fraudulent misrepresentation in 2022 as evidenced by document X at page 47 of the paper book.”

I’ve sat through hearings where Senior Advocates, some of the finest legal minds in the country, get absolutely grilled by benches.

I’ve seen Chief Justice dissect an argument line by line, pointing out every logical flaw, asking hypotheticals that expose weaknesses, and pushing the advocate to concede. If Senior Advocates with 30 years’ experience face this kind of rigorous questioning, you better believe junior AORs will too.

The key is never to be evasive. If you don’t know something, say, “My Lords, I need to check that and will submit a note.”

If the judge points out a precedent that goes against you, don’t pretend it doesn’t exist; distinguish it or explain why it shouldn’t apply to your facts. Intellectual honesty and quick thinking under pressure are what judges respect.

The Art of Briefing Senior Advocates Effectively

Most AORs regularly brief Senior Advocates for oral arguments in important matters, and this requires its own skill set.

You cannot just hand over the file and expect magic. You need to prepare a brief, a concise document (typically 3-5 pages) that tells the Senior Advocate everything they need to know: what happened factually, what the lower court held, what your grounds of appeal are, what the key documents are (with page numbers), what the leading judgments are, what the respondent’s likely arguments are, and what you’re seeking from the Court.

The better your brief, the more effective the Senior’s arguments will be. I spend 2-3 hours preparing a good brief because I know that a well briefed Senior Advocate is worth their substantial fee, while a poorly briefed one wastes everyone’s time.

You also need to manage the Senior’s expectations about the case’s strength, if it’s a difficult matter with low chances of success, say so clearly so they can decide whether to take it on or adjust their argument strategy accordingly.

Professional Challenges in Advocate on Record Practice

Managing Heavy Workload and Multiple Concurrent Cases

Here’s the reality nobody tells you when you’re preparing for the AOR exam: the workload is crushing, especially once you establish a decent practice.

Right now, I’m handling about 25-30 active matters at various stages, some at the admission stage where I’m just trying to get the Court to issue notice, some at the regular hearing stage requiring detailed arguments, some where I’m filing review petitions after adverse orders, and some where I’m just maintaining the matter while the client decides next steps.

Each case has its own timeline, its own deadlines, its own complications, and its own demanding client.

On heavy listing days, I might have seven or eight matters listed across different benches, meaning I’m constantly checking my phone to see which matters got called, running between courtrooms, making hurried submissions because the bench is moving fast, and trying not to miss any matter. The stress of juggling multiple matters simultaneously while ensuring none of them suffers from a lack of attention is immense.

I’ve developed systems, color coded calendars, case management software, and detailed to do lists, but even with systems, there are days when I feel completely overwhelmed.

. What helps is delegation; my juniors handle routine matters, administrative tasks, and initial research, but ultimately, as the AOR, I’m personally responsible for everything. This weight of responsibility never fully lifts.

Managing Client Expectations and Deadline Pressure

Let me share something that keeps me up at night: the gap between what clients expect and what the Supreme Court realistically delivers.

Clients come to me after losing in the High Court, convinced their case is absolutely meritorious and the Supreme Court will surely grant relief. I have to explain that the Supreme Court admits only about 10-15% of Special Leave Petitions because it intervenes only in cases of substantial legal questions or grave injustice.

Even when I explain this clearly at the first meeting, clients often don’t fully absorb it until their SLP is dismissed. Managing that disappointment while maintaining the client relationship is emotionally draining.

Then there’s the timeline issue, clients expect their matters to be heard within weeks, but the reality is that matters can take months or years depending on the Court’s backlog and how the bench prioritizes cases.

I field weekly calls from anxious clients asking, “When will my case be heard?” and having to repeatedly explain that I cannot control the Court’s listing is frustrating for both of us.

The deadline pressure compounds these challenges. Supreme Court practice operates on strict limitation periods, 90 days to file an SLP from the date of the High Court judgment, though condonation of delay is possible with sufficient cause.

When clients approach me on day 85, I have just five days to study the entire case, draft a comprehensive petition, obtain documents, get the client’s verification, and file. These rush jobs are incredibly stressful because any mistake could be fatal to the case, yet I’m working under extreme time pressure.

I’ve learned to charge premium fees for such last minute matters both because of the pressure involved and to discourage clients from leaving things to the last moment, but even so, these situations arise regularly and the pressure never becomes easier to handle.

Building and Managing an Advocate on Record Chamber

When and How Should You Set Up Your AOR Chamber?

Establishing Your Office Within 16 Kilometers of the Supreme Court

One of the first practical requirements after passing the AOR exam is establishing your office within 16 kilometers of the Supreme Court. This isn’t just a formality; it’s a practical necessity for daily Supreme Court practice.

You need a physical space where you can meet clients, store case files, work with your juniors, and manage your practice.

Most new AORs face a dilemma: rent a chamber in an expensive area, or find more affordable office space at a little far away areas.

I started with a shared chamber arrangement where three junior AORs split the rent; this kept costs manageable at ₹12,000 per person monthly while maintaining the 16 kilometer requirement.

After two years of practice, when my income stabilized, I moved to my own chamber closer to the Court. The location decision should balance your budget against your practice volume; if you’re appearing daily in Court, being 5 minutes away saves enormous time and stress compared to 20 minute commutes multiple times daily.

Registering Your Clerk and Meeting Administrative Requirements

The Supreme Court requires every AOR to employ a registered clerk within one month of registration.

This clerk is your link to the Court’s registry; they file documents, collect orders, track matter status, handle routine registry interactions, and ensure procedural compliance.

Finding and registering the right clerk is crucial. Experienced clerks familiar with Supreme Court procedures are invaluable; they know which registry counter handles which type of application, they understand format requirements, they can troubleshoot defects in filings before rejection, and they maintain relationships with registry staff that smooth processing. Most new AORs inherit a clerk from their training AOR or hire someone recommended by established practitioners.

Registering your clerk with the Supreme Court involves submitting an application to the Registry along with the clerk’s documents. The application should include your clerk’s full name, date of birth, residential address, educational qualifications, and contact details. You’ll also need to attach photocopies of the clerk’s identity proof (Aadhaar card, voter ID, or passport), address proof, and educational certificates.

Your clerk must provide passport size photographs and give specimen signatures, which will be maintained on record by the Registry. Once the application is processed, the Registry will assign a unique registration number to your clerk. This registration number must be mentioned on all documents that your clerk signs or files on your behalf, establishing their authority to act for you.

You’re paying this clerk a monthly salary (roughly around ₹15,000-25,000 depending on experience). This is a significant recurring cost that new AORs must budget for from day one. Some AORs share a clerk initially to split costs, though this can create coordination challenges if both AORs need the clerk simultaneously.

When to Hire Your First Junior: Case Volume and Income Triggers

This is one of the most consequential decisions you’ll make as an AOR: when to hire your first junior advocate.

Hire too early when your case volume and income don’t justify it, and you’re burning cash paying a salary you can’t afford.

Hire too late, and you’re drowning in work, missing opportunities, and delivering subpar service to clients because you’re stretched too thin.

Based on my experience and discussions with other AORs, here’s the triggering point: when you’re consistently handling 12-15+ active matters, appearing in court 3-4 days weekly, and earning around ₹1.5-2 lakhs monthly, you’re ready to hire your first junior.

Why these metrics?

At 12-15 matters, you physically cannot handle all the drafting, research, court appearances, and client management yourself.

You need someone to attend to secondary matters while you focus on primary ones, someone to do preliminary research before you finalize petitions, someone to handle routine registry work, and someone to manage client communications.

At roughly ₹1.5-2 lakhs monthly income, you can afford to pay a junior ₹25,000-35,000 monthly salary while still maintaining your own income and covering chamber expenses.

Don’t make the mistake I almost made, waiting until you’re earning ₹3 lakhs monthly before hiring. By that point, you’re so overworked that you’re turning away new clients and your quality of work suffers.

The right junior isn’t just an expense; they’re an investment that allows you to take on more matters, deliver better quality work, and ultimately grow your income beyond what you could achieve alone.

Selecting Juniors: Skills, Cultural Fit, and Training Willingness

Hiring the right junior can make or break your practice.

I’ve seen AORs hire brilliant law school toppers who were terrible juniors because they lacked practical skills, and I’ve seen AORs hire average students who became exceptional juniors because they had the right attitude and work ethic.

Here’s what I look for:

- First, basic competence, they need decent legal research skills, clear legal writing ability, attention to detail, and procedural knowledge. I test this by giving them a small drafting assignment during the interview process.

- Second, willingness to learn, the Supreme Court practice has its own conventions and standards that are different from what they learned in law school or working in High Courts. The best juniors are those who ask questions, take notes, and actively seek to improve rather than assuming they already know everything.

- Third, and perhaps most important, cultural fit, you’re going to spend 8-10 hours daily with this person in close quarters. Are they respectful without being obsequious? Do they take initiative without overstepping? Can they handle stress without becoming irritable? Do they communicate clearly? I’ve learned that a junior with slightly lower legal skills but excellent interpersonal abilities is more valuable than a legal genius who’s difficult to work with.

- Fourth, commitment to Supreme Court practice, I want juniors who aspire to become AORs themselves, not those using this as a temporary placeholder until they find a corporate job. The junior who sees this as their long term career path will invest more effort in learning and growing.

During interviews, I’m explicit about expectations: the work hours are long and sometimes unpredictable, the learning curve is steep, they’ll do substantial drafting and research work, they’ll attend court appearances on matters I assign them, and they should expect to work under me for at least 2-3 years before moving independently or joining another AOR.

I’m also transparent about salary (around ₹25,000-30,000 monthly for fresh graduates, around ₹35,000-45,000 for those with 2-3 years’ experience) and growth prospects (annual increments, bonus for exceptional work, recommendations for AOR training certificates when they’re ready). This transparency upfront prevents misunderstandings later and attracts juniors who genuinely want this career path.

What to Delegate and What to Handle Yourself?

Delegation is an art that took me two years to learn.

Initially, I micromanaged everything, convinced that only I could do things properly. This was exhausting and prevented me from taking on more cases.

Then I swung to the opposite extreme, delegating too much, and had a petition returned by the registry with defects because my junior missed a formatting requirement.

I’ve now found a balance.

Here’s what I consistently delegate to my juniors:

- Preliminary legal research (identifying relevant judgments, statutes, and articles, though I always review their research before using it in petitions).

- Drafting of routine applications (condonation of delay, impleadment, intervention, I review and finalize but they prepare the first draft).

- Maintaining the case management system (updating matter status, tracking deadlines, organizing files).

- Client communication for routine queries (hearing dates, order copies, procedural questions, substantive legal advice still comes from me).

- Attendance in court on secondary matters (those where I’m confident they can make basic submissions if the matter is called).

- Filing tasks (taking documents to the registry, collecting orders, following up on defects).

What I never delegate:

- Final drafting of Special Leave Petitions and other primary petitions, I might have juniors prepare first drafts but I substantially rewrite and finalize because the quality of the petition determines whether the Court even admits your case.

- Arguments before the Court on primary matters require years of experience and I won’t risk client interests by sending juniors to argue complex matters.

- Client consultations on case strategy, clients engage me for my judgment and experience, and major strategic decisions must be mine.

- Review of all documents before filing, even if a junior drafted something, I read every page before it goes to the registry because my name and AOR code are on it, making me personally responsible.

The key is trusting juniors with tasks that help them learn and that free up your time for high value work, while retaining personal control over tasks where your expertise and judgment are irreplaceable.

What Are the Financial Realities of Chamber Management of an Advocate on Record?

Chamber Expenses: Rent, Junior Salaries, and Operating Costs

Let me break down the real costs of running an AOR chamber because nobody discusses this openly.

My monthly chamber expenses are approximately ₹1,20,000-1,30,000, and here’s how that breaks down.

- Office rent: ₹35,000 monthly for a 350 sq ft chamber in Jangpura (10-15 minutes from the Supreme Court). This is relatively affordable; chambers within the Supreme Court complex or immediate vicinity cost ₹40,000-60,000 for similar space.

- Electricity, water, and maintenance: ₹3,000-4,000 monthly (varies by season, higher in summer when air conditioning runs all day).

- Junior advocate salaries: ₹70,000 monthly total (₹35,000 each for two juniors). This is the single largest expense, but absolutely necessary once your practice volume justifies it.

- Clerk salary: ₹20,000 monthly for an experienced clerk who knows Supreme Court procedures inside out.

- Internet and phone: ₹2,500 monthly for reliable high speed internet (essential for research, e filing, and video conferences) and a dedicated practice phone line.

- Office supplies and equipment: ₹3,000-5,000 monthly, including printing/photocopying costs, stationery, paper, files, stamps, and occasional equipment repairs or replacements.

- Legal research subscriptions: ₹5,000 monthly for SCC Online and Manupatra (both essential for comprehensive Supreme Court judgment research).

- Professional memberships: ₹2,000 monthly amortized cost for Supreme Court Bar Association membership and other professional associations.

This totals ₹1,20,500-1,30,500 monthly in fixed overhead before earning a single rupee.

To just break even on overhead, I need to earn approximately ₹1.5 lakhs monthly.

To pay myself a reasonable salary and save for taxes, I need to earn ₹2.5-3 lakhs monthly minimum.

This is why building a consistent case flow is so critical; you cannot survive on sporadic cases when your overhead is ₹1.2 lakhs monthly. This financial pressure is rarely discussed in the glamorous narratives about AOR practice, but it’s the reality that keeps you hustling for new matters, maintaining relationships with referring lawyers, and sometimes taking on cases you wouldn’t prefer just to keep the cash flow steady.

Balancing Income Growth with Team Investment

Here’s the paradox of building an AOR practice: you need a strong team (juniors, clerks, research support) to handle growing case volume, but building that team requires significant investment that reduces your take home income in the short term.

In my third year of practice, I faced this exact dilemma. My income had grown to ₹2.5 lakhs monthly, but I was working 12-hour days and turning away potential clients because I couldn’t handle more cases.

I knew I needed to hire a second junior, which would cost ₹35,000 monthly, plus increase my supervision time. That ₹35,000 was a significant chunk of my profit reducing my take home by nearly 15%. But I also recognized that without additional help, I’d hit a ceiling; I could never scale beyond ₹3 lakhs monthly income no matter how hard I worked, because there are only so many hours in a day and only so many matters one person can handle.

I made the investment and hired the second junior. For the first three months, it felt like a mistake, my take home income dropped, I spent time training the new junior instead of doing billable work, and productivity initially decreased as we adjusted to the new team dynamic.

But by month four, the benefits became clear. I could take on 8-10 additional matters that I would have previously declined. The juniors handled routine work while I focused on complex petitions and court appearances. My income grew to ₹3.5 lakhs monthly within six months of the hire, more than offsetting the ₹35,000 salary expense. By the end of the year, I was earning ₹4-4.5 lakhs monthly, growth that would have been impossible without team expansion.

The lesson: you have to invest before you see returns. Building a team reduces short term income but increases your capacity for long term growth. The key is timing the investment right. Don’t hire when you’re barely covering overhead, but don’t wait until you’re so overwhelmed that you’re losing clients and burning out.

The sweet spot is when you’re consistently earning 50-60% above your overhead costs and turning away work because you lack bandwidth. That’s when team investment makes strategic sense. It’s scary to reduce your take home income voluntarily, but successful AORs understand that you cannot scale a practice alone; you need a team, and teams require investment.

Income Structure of an AOR

Earnings of Advocate on Record by Experience

Let me give you the unfiltered truth about AOR earnings because most articles provide wildly optimistic projections without explaining the reality.

A new AOR typically earns between ₹12,00,000 to ₹20,00,000 annually, assuming you’re actively building your practice. This isn’t passive income; you’ll be filing cases, drafting petitions, and attending hearings regularly to hit these numbers.

Mid-career AORs with 10 years of practice comfortably earn ₹30-50 lakh annually. At this stage, you’ve built a referral network, established corporate client relationships, and your fees have increased substantially. You’re no longer chasing every case; clients are seeking you out, and you can be selective about the matters you take on.

Senior AORs with 15+ years of practice and a strong reputation regularly cross ₹1 crore in annual income. Some top practitioners earn ₹2-3 crore or more, especially those with specialized practices in constitutional law, taxation, or corporate matters. These are the advocates whose names appear in landmark Supreme Court judgments, and their billing rates reflect their expertise and track record.

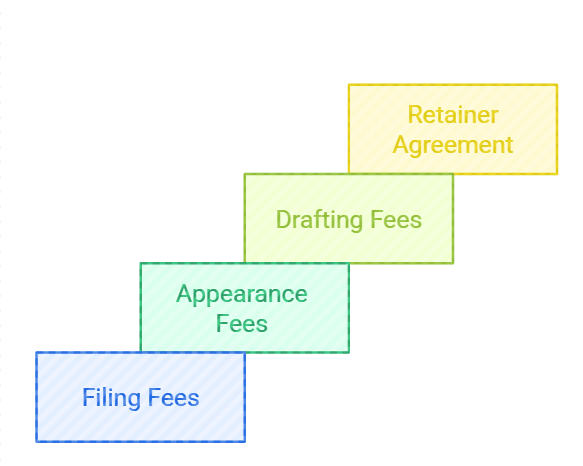

Fee Structures: Filing, Appearance, Drafting and Retainers

Filing fees

As a new AOR, you’ll typically charge ₹10,000-15,000 just for signing the vakalatnama and completing the filing formalities with the Supreme Court Registry. Within 3-4 years of practice, your filing fees typically increase to ₹20,000 for standard matters. By the time you’re a senior AOR with 10+ years of experience, you might charge higher for signing and filing, depending on case complexity and client profile.

Appearance fees

As a new AOR, you’ll charge ₹30,000-50,000 per appearance for most matters. If the case requires extended arguments or multiple benches in a single day, you might charge ₹50,000. This is per appearance, not per case. With 5-10 years of AOR experience, your appearance fees increase to ₹50,000-80,000 for standard hearings and ₹1 lakh for complex arguments or final hearings. Senior AORs with 15+ years often charge ₹1.5 lakh+ per appearance, especially for high stakes matters. Some top tier AORs charge ₹2 lakh + per hearing.

Drafting fees

In your first 2-3 years as an AOR, you’ll charge ₹20,000-25,000 per petition for straightforward SLPs or writ petitions. This is for a complete draft, legal research, issue identification, ground formulation, precedent citations, and the actual petition drafting. After 3-5 years of AOR practice, your drafting fees jump significantly. You’re now charging ₹50,000-75,000 for standard petitions and ₹1-2 lakh for complex constitutional, corporate, or tax matters

Retainership agreement

This is where clients pay you a monthly fee for ongoing Supreme Court work. This is the holy grail of AOR income because it provides predictability. A company or law firm retains you for a fixed monthly/annual fee of ₹25,000 per month to ₹5 lakh per year to handle all their Supreme Court matters. You get predictable income, and they get priority attention and preferred rates. Even one good retainer client can stabilize your practice finances significantly.

Impact of Practice Area on AOR Income

Not all practice areas are equally lucrative in Supreme Court practice, and understanding this can help you make strategic decisions about where to focus your expertise.

- Constitutional law matters, petitions under Article 32, constitutional challenges to statutes, PIL matters are prestigious and intellectually satisfying but often not the highest paying work. Many PIL matters are pro bono or low fee because the petitioners are civil society organizations or individuals without deep pockets. However, building a constitutional law reputation can lead to high paying corporate constitutional challenges (companies challenging regulatory provisions, tax statutes, etc.), so there’s a longer term payoff.

- Tax litigation (income tax, GST, customs) is consistently lucrative because the amounts in dispute are often substantial, corporate clients are involved, and they can afford significant legal fees. The downside is that tax law is technically complex, constantly changing, and requires continuous learning. You’re competing with specialized tax advocates who’ve spent decades in this field, so breaking in requires substantial expertise.

- Service matters (government employment disputes, pension issues, promotion challenges) are bread and butter work for many AORs. These cases are numerous, clients are motivated (their livelihoods are at stake), and fees are moderate but steady. The challenge is that service matters can be factually intensive, require detailed record examination, and appeals often turn on narrow procedural points. Building a service law practice provides consistent income but might not lead to the highest fee levels.

- Criminal appeals to the Supreme Court can be extremely lucrative when high profile accused or serious charges are involved. However, criminal work is emotionally taxing, the ethical complexities are significant (defending accused in heinous crimes), and you’re dealing with liberty and life and death issues. Not all AORs are comfortable with criminal defense work.

- Commercial and company law matters, contract disputes, shareholder disputes, and insolvency appeals typically involve corporate clients with substantial legal budgets. The downside is that you’re competing with large law firms that have entire corporate litigation teams and existing client relationships. Breaking into corporate work as an individual AOR requires either specialized expertise or strong referral networks with corporate lawyers.

Career Growth as an Advocate on Record

Building a Reputation in Supreme Court Practice Through Quality Work

Reputation is everything in Supreme Court practice, and it’s built slowly through consistent quality work, not through marketing or self promotion.

Here’s what I’ve learned about reputation building:

First, every petition you file is a representation of your work that judges, registry staff, and other lawyers see. Sloppy drafting, procedural non compliance, or weak legal arguments damage your reputation even in matters you lose. Conversely, a well drafted petition that properly frames legal issues earns respect even if the Court doesn’t admit it.

Second, your conduct in court matters enormously. Judges remember advocates who are prepared, concise, honest about weaknesses in their case, and respectful of the Court’s time. They also remember those who are unprepared, longwinded, evasive, or attempt to mislead. One senior judge’s positive comment about your work can lead to other judges noticing you favorably.

Lastly, how you handle loss matters as much as how you handle victory. I lost an important matter last year where the Court dismissed my client’s SLP. I could have blamed the Court, made excuses, or promised the client we’d file a review (which had minimal chances). Instead, I explained clearly why the Court ruled against us, acknowledged where my arguments hadn’t persuaded, discussed whether a review was worth the cost (ultimately advising against it), and helped the client understand their options going forward.

That client referred two new clients to me within three months because they respected my honesty and professional handling of the loss. AORs who overpromise, blame judges for losses, or handle defeat unprofessionally might win individual matters but lose long term reputation.

Networking with other Advocates, Senior Advocates and Supreme Court Bar Association

Supreme Court practice is built on relationships as much as legal skills, and strategic networking is essential for career growth. Your primary network is other AORs, these are your peers, your potential referral sources, and your professional community.

I make it a point to chat with other AORs in the Court canteen, attend Bar Association events even when I’m tired, and offer help to AORs who are stuck on procedural questions. This goodwill is reciprocal. When I needed someone to cover my matter last month because I had two hearings scheduled simultaneously in different courtrooms, an AOR I’d helped previously stepped in immediately. When another AOR has a matter outside their expertise but within mine, they refer it to me. These informal networks drive substantial work.

Building relationships with Senior Advocates is more delicate because the power dynamic is asymmetric; they’re established, you’re building your career.

The key is demonstrating value: prepare excellent briefs when you engage them, be responsive to their queries, handle all procedural aspects flawlessly so they can focus on arguments, and show genuine respect for their experience without being obsequious.

Senior Advocates remember AORs who make their work easier, and they’ll specifically request you for future briefs from their clients. Some Senior Advocates also mentor younger AORs, providing guidance on case strategy, argument techniques, and career development.

The Supreme Court Advocates On Record Association (SCAORA) plays a crucial role in professional networking and development. SCAORA organizes continuing education programs on recent Supreme Court judgments, procedural changes, and substantive legal topics. These programs keep you current while providing networking opportunities with other AORs.

I serve on SCAORA’s Legal Aid Committee, which involves representing indigent litigants pro bono, and this service has introduced me to senior AORs I wouldn’t have otherwise met and has enhanced my reputation as someone committed to the profession beyond just commercial practice.

These intangible benefits of networking, reputation, referrals, mentorship, and community support are often more valuable than any single case fee.

Conclusion

The life of an Advocate on Record is simultaneously exhilarating and exhausting, prestigious and demanding, lucrative and stressful.

It’s not the glamorous existence that outsiders imagine; it’s long hours in your chamber drafting petitions, running between courtrooms hoping you don’t miss a hearing, managing client anxieties, juggling multiple deadlines, and constantly learning because the law never stops evolving. But it’s also intellectually stimulating in ways few other careers match. Every case presents novel legal questions, every hearing tests your advocacy skills, every victory validates years of hard work and study, and every interaction with brilliant judges and senior advocates teaches you something new.

If you’re considering the AOR path, understand that it requires genuine passion for Supreme Court practice, not just attraction to the prestige or income potential. The successful AORs I know love the intellectual challenge of constitutional and appellate law, thrive under the pressure of Supreme Court practice, find meaning in shaping legal precedents at the highest level, and are willing to make significant personal sacrifices for their professional goals.

If that describes you, this career can be immensely rewarding. If you’re seeking work life balance, predictable hours, or quick wealth, look elsewhere; this isn’t that path.

The AOR designation opens doors to the pinnacle of India’s legal profession, but walking through those doors and building a sustainable practice requires resilience, continuous learning, strategic thinking, and years of dedicated effort. For those willing to put in that effort, the professional and personal rewards of AOR practice are extraordinary.

Frequently Asked Questions

What does a typical day look like for an Advocate on Record?

An AOR’s day starts around 7:30 AM with chamber prep, followed by court from 10:30 AM to 4 PM and post court work till late evening. Nights are often for drafting and research, and weekends rarely go completely free; flexibility is key.

What skills are most important for AOR success?

Mastery of Supreme Court Rules, strong drafting and advocacy skills, quick legal reasoning, case management, composure under pressure, ethical judgment, and continuous learning are vital for AOR success.

How do AORs manage work life balance with demanding schedules?

Work life balance is tough. AORs manage it by setting strict boundaries, protecting family time, delegating tasks, taking planned breaks, and focusing on sustainable work habits over perfect balance.

What challenges do new AORs face in their first year of practice?

New AORs struggle with building clients, irregular income, procedural learning, chamber expenses, and credibility. The first year is survival mode, financially and professionally, until reputation builds.

How much can an AOR realistically earn?

A new AOR typically earns between ₹12,00,000 to ₹20,00,000 annually, assuming you’re actively building your practice. Mid career AORs with 10 years of practice comfortably earn ₹30-50 lakh annually. Senior AORs with 15+ years of practice and a strong reputation regularly cross ₹1 crore in annual income. Some top practitioners earn ₹2-3 crore or more, especially those with specialized practices in constitutional law, taxation, or corporate matters.

Do AORs need to live in Delhi or can they practice from other cities?

You need a registered office within 16 km of the Supreme Court, but many AORs live elsewhere and visit Delhi for listings. With good coordination and support, hybrid practice is feasible.

How many hours per week do AORs typically work?

AORs usually work 60–75 hours weekly. Long hours, weekend prep, and late night drafting are normal in this high-intensity practice.

Can AORs specialize in specific areas of law?

Yes, most AORs maintain broad practice but develop expertise in 1–2 areas like tax, constitutional or service law. Specialization boosts reputation and fees but takes years of consistent focus.

How do junior advocates working with AORs get paid?

Juniors earn fixed monthly salaries of roughly ₹25,000–35,000 for freshers, rising to around ₹50,000–75,000 with experience. Bonuses are occasional, and the setup is more mentorship than partnership.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications