AOR full form stands for Advocate on Record, a special designation granted by the Supreme Court of India to advocates authorized to file and represent cases before it. This guide explains the origin, meaning, qualifications, Rules under Article 145 and Order IV, and why becoming an AOR is one of the most prestigious milestones in Indian legal practice.

Table of Contents

Walk into any district court in India, and you’ll find hundreds of lawyers jostling for clients, filing cases, and arguing matters. Walk into a High Court, and the crowd thins considerably, maybe a few thousand qualified advocates across the state.

But step into the Supreme Court of India, and you’ll discover something peculiar: only 3,789 lawyers out of nearly 20 lakh in the entire country can actually file a case there.

This isn’t about seniority, experience, or even legal brilliance.

It’s about three letters: AOR, which stands for Advocate on Record.

And if that sounds like just another credential in India’s professional qualifications, here’s what makes it different: the Supreme Court itself decides who gets this title, through rules it frames under constitutional authority that no government or legislature can override.

Pass their examination, complete their training requirements, meet their standards, or you simply cannot practice there. Period.

What’s fascinating isn’t just the exclusivity, but what it reveals about power and access in India’s legal system. Why does the country’s highest court need such strict gatekeeping?

And most importantly, what does this mean for you, whether you’re a law student evaluating career paths, a litigant wondering why your excellent lawyer suddenly needs to “engage an AOR,” or simply someone trying to understand how India’s judiciary actually works beyond the courtroom theatrics shown on television?

This guide breaks down everything about the AOR full form, from its constitutional origins to the practical realities that official sources won’t tell you.

Are you excited? Let us begin.

What is the AOR Full Form in Law?

AOR stands for Advocate on Record, a specialized category of advocates authorized to practice before the Supreme Court of India. This isn’t just another acronym in legal jargon; it represents a constitutional framework that governs who can represent clients before India’s apex court.

Understanding the AOR full form matters because it reveals how India’s legal system ensures quality control at its highest judicial level. Unlike regular advocates who can practice in district courts, High Courts, or tribunals across the country, only AORs have the exclusive right to file cases and represent parties in the Supreme Court. Out of approximately 15-20 lakh enrolled advocates in India, only about 3,789 are registered as Advocates on Record as of 2025, making this one of the most selective professional qualifications in Indian law.

The AOR designation exists under Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, which were framed by the Supreme Court under constitutional authority granted by Article 145 of the Constitution of India.

This constitutional backing means the AOR system isn’t merely an administrative convenience; it’s a fundamental part of how Supreme Court practice is regulated.

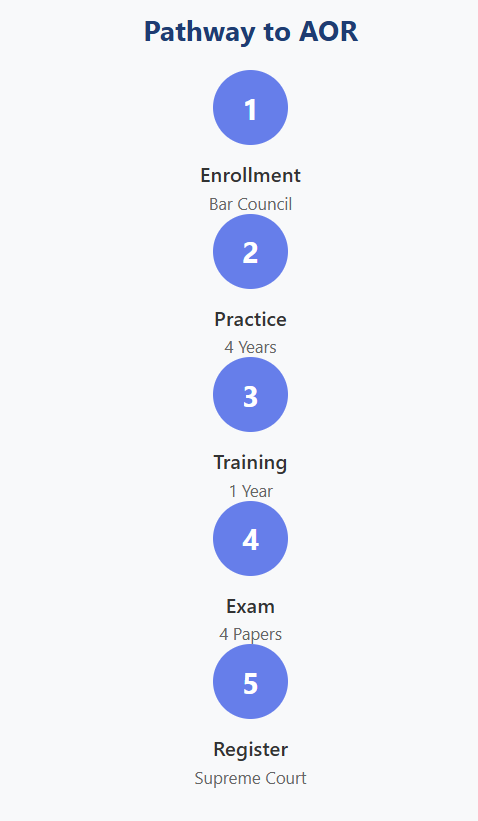

When you see “AOR” after an advocate’s name or on Supreme Court documents, you’re seeing confirmation that this person has met rigorous qualification standards, including four years of general practice, one year of specialized training, and passing a challenging Supreme Court examination.

Origin and Meaning of the AOR Full Form

The term “Advocate on Record” has a specific legal meaning that goes beyond just being an advocate who practices in the Supreme Court.

An AOR is literally an advocate whose name appears “on record” with the Supreme Court Registry as the authorized representative for a party in a case.

This on-record status gives them exclusive authority to file pleadings, petitions, and other documents on behalf of their clients before the apex court.

The term distinguishes between advocates who are merely enrolled with State Bar Councils and those who have earned the additional qualification to be registered with the Supreme Court itself.

The AOR system was first introduced in 1966 when the Supreme Court framed the original Supreme Court Rules using powers granted under Article 145 of the Constitution.

The system was designed to ensure that advocates practicing before India’s highest court possessed specialized knowledge of Supreme Court procedures, rules, and practices that differ significantly from trial courts or High Courts.

Over the decades, these rules evolved, with major amendments in 2013 that updated the framework while maintaining the core principle of specialized qualification for Supreme Court practice.

The “Advocate on Record” terminology reflects a practical legal reality: in Supreme Court matters, there must always be one advocate who takes complete responsibility for the case’s procedural compliance, document filing, and communication with the Court Registry.

This advocate, the AOR, serves as the official point of contact between the client and the Court. Even when senior advocates argue cases before the Supreme Court, they must be “instructed” by an AOR who remains the advocate of record. This system ensures accountability and procedural compliance at the apex court level.

Why “On Record” in AOR Full Form is Significant?

The phrase “on record” signifies that the Supreme Court Registry maintains an official record of this advocate as the authorized representative for a particular party in a case.

This isn’t merely symbolic; it creates legal responsibilities and exclusive rights.

All court notices and communications go to the AOR, who must ensure proper filing of documents, payment of court fees, and compliance with Supreme Court Rules.

The “on record” status means you’re personally accountable to the Court for everything filed in your client’s name.

Constitutional and Legal Basis for AOR Full Form Designation

Article 145 of the Constitution of India

Article 145(1) of the Constitution grants the Supreme Court the power to make rules for regulating its general practice and procedure, subject to the approval of the President of India.

This constitutional provision is the foundation on which the entire AOR system rests. The framers of the Constitution recognized that the Supreme Court, as the apex judicial body, needed authority to determine who could practice before it and what qualifications they must possess.

This constitutional power ensures that the AOR system isn’t subject to legislative interference and can be adapted by the Court itself as needed.

Under Article 145, the Supreme Court has specifically framed rules concerning “persons practicing before the Court” as part of its broader rule-making authority.

This includes the power to create specialized categories of advocates, set qualification requirements, and establish examination systems to test competence.

The AOR designation emerged from this constitutional authority, creating a framework where only advocates who meet specific standards can independently file cases before the Supreme Court. This constitutional backing gives the AOR system legitimacy and ensures its requirements are legally enforceable.

Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules 2013

Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, contains the detailed provisions governing the AOR system.

Rule 1(b) of Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 explicitly states that “no advocate other than an advocate on record shall be entitled to file any appearance or act for a party” in the Supreme Court.

This rule creates the exclusive filing rights that define the AOR designation.

It further clarifies that no advocate can appear and plead in the Supreme Court unless instructed by an AOR or specifically permitted by the Court. These provisions establish the legal monopoly that AORs hold over Supreme Court practice.

Rule 5 of Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 sets out the detailed eligibility criteria for becoming an AOR, including the requirement of four years of practice, one year of specialized training, and passing the AOR examination.

Rule 6 of Order IV of the Supreme Court Rules, 2013 specifies grounds for disqualification, such as conviction for offenses involving moral turpitude.

Together, these rules create a comprehensive framework that governs everything from initial qualification to ongoing professional conduct.

The Supreme Court Rules, 2013, modernized the original 1966 framework while maintaining its fundamental purpose: ensuring that only properly qualified advocates can practice independently before India’s highest court.

What Makes an AOR Different from a Regular Advocate?

Exclusive Right to File Cases in the Supreme Court

The most fundamental difference between an AOR and a regular advocate lies in filing rights.

Only an Advocate on Record can file a vakalatnama (the document authorizing an advocate to represent a client) in the Supreme Court. This means no matter how senior or experienced a regular advocate might be, they cannot independently file a case before the Supreme Court without an AOR.

This exclusive right extends to all types of Supreme Court filings, such as Special Leave Petitions under Article 136, writ petitions under Article 32, appeals, review petitions, and original suits under Article 131.

This filing monopoly isn’t about creating an elite club; it serves a practical purpose.

When an AOR files a document, the Registry knows that this person has demonstrated competence through rigorous examination and training. They understand Supreme Court procedures, fee structures, documentation requirements, and compliance standards. This system prevents procedural delays and ensures that cases reaching India’s highest court meet basic quality thresholds.

The exclusive filing right also creates a clear accountability chain. In every Supreme Court matter, there’s always one AOR who takes full responsibility for the case’s procedural aspects.

Authority to Act and Plead on Behalf of Parties

An AOR doesn’t just have filing rights; they also have the authority to act and plead on behalf of parties before the Supreme Court.

“Acting” refers to handling all procedural and administrative aspects of a case, while “pleading” refers to presenting arguments before the Court.

Unlike regular advocates who can only appear if instructed by an AOR, an Advocate on Record can independently represent clients in Supreme Court proceedings. This means they can attend hearings, make oral submissions, argue matters before different benches, and handle all aspects of Supreme Court litigation.

However, the Supreme Court system allows for specialization through collaboration. While AORs have the right to plead, they often brief senior advocates to present complex arguments in major constitutional or commercial matters.

In such cases, the AOR remains the advocate of record and continues handling procedural aspects, while the senior advocate focuses on oral advocacy. The senior advocate can only participate because the AOR instructs them; without an AOR, even the most distinguished senior advocate cannot appear before the Supreme Court.

Personal Responsibility for Procedural Compliance

When you become an AOR, you assume personal liability for everything filed in your client’s name.

The Supreme Court recently reinforced this in a 2025 ruling, holding that AORs bear full responsibility for the accuracy of petitions even if drafts were prepared by other advocates.

This personal accountability means you’re not just a middleman for filing documents, you’re professionally responsible for verifying facts, ensuring legal soundness, and maintaining ethical standards in everything you submit to the Court.

If a petition contains false statements or misleading information, the AOR can face professional consequences, including contempt proceedings.

This responsibility extends to financial compliance as well.

The AOR is personally liable for payment of all court fees and charges associated with a case. If fees aren’t paid properly, the Registry holds the AOR accountable, not the client.

This creates a strong incentive for AORs to maintain proper accounts and ensure all financial aspects of Supreme Court practice are handled professionally.

The personal liability framework ensures that AORs take their role seriously and maintain high standards in Supreme Court practice.

Basic Requirements to Become an AOR

What Educational Qualifications Are Needed to Become an AOR?

Law Degree (LLB/BA LLB) Requirement

The foundational educational requirement for becoming an AOR is holding a Bachelor of Laws (LLB) degree from a Bar Council of India recognized institution.

This can be either a three year LLB program (for graduates who already hold another bachelor’s degree) or a five year integrated program like BA LLB, BBA LLB, or B.Com LLB.

The degree must be from a university recognized by the University Grants Commission to ensure it meets minimum educational standards.

Unlike some legal specializations that require postgraduate degrees, an LLM is not mandatory for an AOR qualification; the focus is on practical experience rather than advanced academic credentials.

Clearing the AIBE Examination

Since 2010, all advocates must clear the All India Bar Examination (AIBE) conducted by the Bar Council of India before they can practice law in India.

The AIBE is a basic competency test covering fundamental legal subjects, and you must pass it to be enrolled with any State Bar Council.

For AOR aspirants, this means you need AIBE clearance as a pre-requisite, without it, you cannot begin the four year practice period that’s required before AOR training.

The AIBE itself is relatively straightforward compared to the AOR examination, but it’s a necessary stepping stone in your journey.

Bar Council and State Roll Enrollment

You must be enrolled with any State Bar Council in India as a practicing advocate, and your name must remain on the State Bar Council roll continuously for at least four years before you can commence AOR training.

This enrollment gives you the legal right to practice as an advocate in courts, tribunals, and before authorities.

The State Bar Council enrollment serves as proof that you’re a qualified legal professional in good standing.

When you apply for AOR training and examination, you’ll need to submit your enrollment certificate showing the date you first enrolled, as this determines when you become eligible for the AOR pathway.

What is the Minimum Practice Experience Required to Become an AOR?

Four Years of Practice as an Advocate

The Supreme Court Rules, 2013 mandate that your name must be borne on the roll of a State Bar Council for at least four years before you can begin AOR training.

This four year period starts from the date of your initial enrollment with any State Bar Council.

During these four years, you’re expected to gain practical legal experience, whether through litigation in lower courts, High Court practice or working with law firms.

The Supreme Court doesn’t prescribe specific types of practice, but the underlying principle is that you should have substantial real world legal experience before attempting to specialize in Supreme Court practice.

It’s important to understand that internships during law school don’t count toward this four year requirement. The clock starts only after you’ve completed your law degree, passed the AIBE, and enrolled with a State Bar Council as a practicing advocate.

This ensures that AOR candidates bring genuine professional experience rather than just academic knowledge when they begin specialized Supreme Court training.

One Year Training Under Senior AOR

After completing four years of general practice, you must undergo one year of specialized training under a senior Advocate on Record who has at least 10 years of experience.

This training is hands on and intensive; you’ll accompany your training AOR to Supreme Court hearings, learn Supreme Court specific procedures, draft petitions and pleadings under supervision, understand the filing system and Registry protocols, and absorb the professional culture of Supreme Court practice. The training year is your introduction to how the apex court actually functions, from the cause list system to the mentioning procedure for urgent matters.

Your training AOR must certify at the end of one year that you’ve completed the requisite training satisfactorily. This certification is mandatory for your AOR examination application; without it, you cannot sit for the exam.

The training requirement ensures that every AOR candidate has been mentored by an experienced practitioner who can vouch for their readiness to practice independently before the Supreme Court.

What is the AOR Examination?

Overview of the Supreme Court Exam

The AOR examination is conducted annually by the Supreme Court of India, typically in May or June.

It’s a four day examination consisting of four papers of 100 marks each, viz:

(1) Practice and Procedure, (2) Drafting, (3) Professional Ethics and Advocacy, and (4) Leading Cases. You can refer to my article on the AOR Exam syllabus to know what each paper covers.

All papers are descriptive in nature, requiring detailed written answers rather than multiple-choice responses.

You have three hours for each paper (except for drafting paper, wherein you get 30 minutes extra), and the examination is conducted offline in traditional pen and paper format.

The passing criteria are rigorous: you must secure at least 50% marks in each individual paper and an aggregate of 60% across all four papers combined.

This dual requirement means you cannot afford to neglect any paper; failing even one paper by a single mark means failing the entire examination.

The pass rate historically hovers around 19-24%, making it one of the more challenging professional examinations in Indian law. You’re allowed a maximum of five attempts to clear the exam, and each appearance (even if you write only one paper) counts as one attempt.

If you want to learn tips for cracking the AOR Exam, you can refer to this article on the Indian Lawyers Guide to Cracking the Supreme Court Advocate on Record (AOR) exam.

Exemption from AOR Training or Examination

The Supreme Court Rules, 2013, provide limited exemptions from the training and examination requirements.

Solicitors on the rolls of the Bombay Incorporated Law Society who have been on a State Bar Council roll for at least seven years are exempt from both training and examination.

Additionally, the Chief Justice of India has discretionary power to grant exemptions from training for advocates with at least 10 years of practice, or from both training and the four year requirement for advocates with special knowledge or experience in law.

However, these discretionary exemptions are rarely granted and typically reserved for truly exceptional circumstances.

Disqualifications for Exam

If you’ve been convicted of an offense involving moral turpitude (such as fraud, forgery, or corruption), you’re disqualified from appearing for the AOR examination unless your conviction has been stayed by a court or two years have passed since you completed your sentence or paid the fine.

This disqualification doesn’t apply if you were released on probation without any penalty being imposed. These disqualification grounds ensure that only advocates of good character and professional standing can become AORs, maintaining the integrity of Supreme Court practice.

Application Process and Required Documents to become an AOR

The AOR examination application process typically opens in March or April each year when the Supreme Court releases an official notification on its website.

You’ll need to download the application form, fill it completely with accurate details, and submit it along with the required documents: a recent passport size photograph affixed to the application, a self attested copy of your State Bar Council enrollment certificate, and your training completion certificate from your training AOR.

After your application is verified by the Registry, you’ll receive a confirmation email instructing you to pay the examination fee (typically ₹750) within 2 days through online bank transfer.

Once you’ve paid the fee, you must send hard copies of your application form, enrollment certificate, training completion certificate, and payment receipt to the Supreme Court Registry via post or courier.

The final acceptance of your application depends on the receipt of these hard copies, so ensure you send them well before the deadline to account for postal delays.

Post-Examination Enrollment and Certification Process to become an AOR

If you successfully pass the AOR examination, the Supreme Court publishes results typically by December or January, listing successful candidates by name and roll number.

Once the results are announced, you can proceed with AOR registration by submitting a registration application to the Supreme Court Registry along with several documents: your pass certificate and proof of office establishment in Delhi. You must also pay a nominal registration fee of ₹250.

A critical requirement is establishing a registered office within 16 kilometers of the Supreme Court building and employing a registered clerk within one month of your AOR registration.

Once all requirements are satisfied and your application is approved, you’ll be assigned a unique AOR code and officially registered as an Advocate on Record.

This entire post-examination process typically takes 2 to 8 weeks, depending on documentation completeness and Registry workload.

Roles and Responsibilities of an AOR Designation

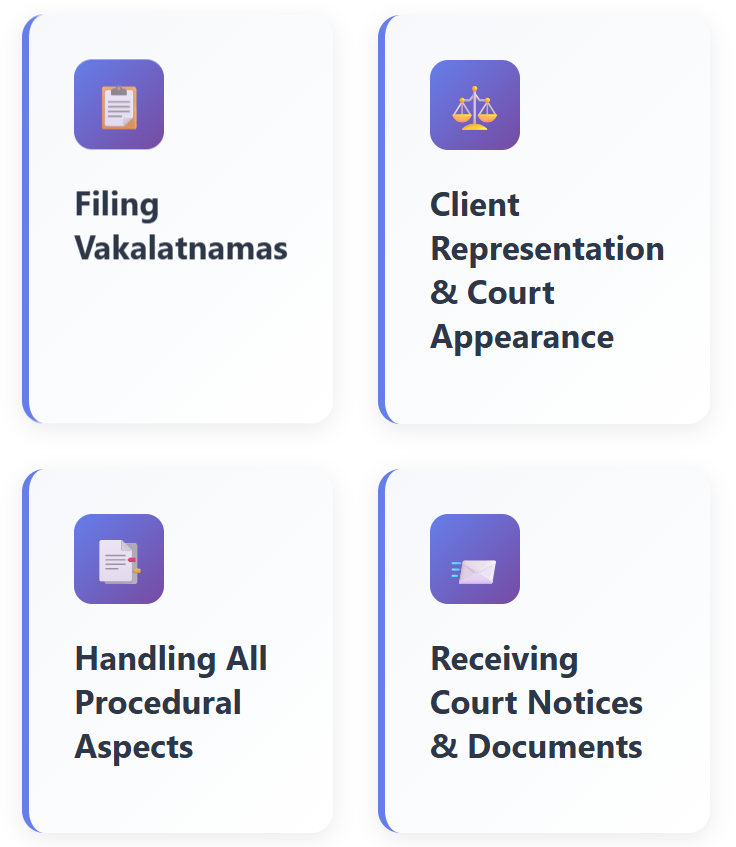

Filing Vakalatnamas on Behalf of Clients

The vakalatnama is the foundational document in Supreme Court practice; it’s your client’s written authorization for you to represent them before the Court.

Only an AOR can file a vakalatnama in the Supreme Court, making this an exclusive responsibility of the designation.

When you file a vakalatnama, you’re formally entering your name on record as the client’s authorized representative, which triggers all your subsequent responsibilities under Supreme Court Rules.

Filing a vakalatnama isn’t just a procedural formality; it creates a professional relationship with legal and ethical obligations. Once you’re the AOR on record, you cannot simply withdraw from the case without the Court’s permission.

You must continue representing the client through the matter’s conclusion unless the Court specifically permits your withdrawal or the client terminates your engagement. This ensures continuity in Supreme Court cases and prevents clients from being left unrepresented at critical stages.

Client Representation and Court Appearance

As an AOR, you serve as your client’s primary representative before the Supreme Court.

This means you have the authority to attend all hearings, make submissions before the Court, argue matters if you choose to present oral arguments yourself, accept or contest adjournments, and make decisions on procedural matters on your client’s behalf.

When a judge asks “Who is appearing for the petitioner?” in Supreme Court proceedings, the AOR (or senior counsel instructed by the AOR) must respond and present the client’s case.

Your representation extends beyond just appearing in court. You’re responsible for keeping clients informed about case developments, advising them on legal strategy and settlement options, explaining Court orders and their implications, and obtaining instructions on significant decisions.

The AOR serves as the bridge between the client and the Supreme Court, translating complex legal proceedings into understandable terms while ensuring the client’s interests are protected at every stage.

Handling All Procedural Aspects of Supreme Court Cases

Supreme Court procedure is significantly more complex than trial courts or High Courts, and the AOR shoulders responsibility for navigating this complexity.

You must master the cause list system to track when your cases are being heard, understand mentioning procedures for getting urgent matters listed, know the filing requirements for different types of petitions, comply with Registry protocols and documentation standards, and ensure timely compliance with all Court orders and directions.

This procedural expertise is what justifies the AOR system; the Court can rely on AORs to maintain procedural discipline.

Procedural compliance includes seemingly mundane but crucial tasks like ensuring correct court fee payment, proper pagination and compilation of documents, appropriate certification of copies, timely filing of written submissions when directed, and proper service of notices on opposite parties.

Many cases face dismissal or delay, not because of weak legal merits but due to procedural defects. Your role as an AOR is to ensure your client’s case never suffers from such preventable problems.

Receiving Court Notices and Documents

All official communication from the Supreme Court is sent exclusively to the AOR on record. The Supreme Court doesn’t communicate directly with clients or with other advocates who might be assisting in the case.

This makes you the information medium between the Court and your client. You must promptly collect notices from the Registry, review them carefully for compliance deadlines or action required, communicate their contents to your client, and take necessary follow up action within prescribed time limits.

This responsibility for receiving and acting on Court notices creates significant accountability. If you miss a notice or fail to act on it in a timely manner, your client’s case could be dismissed for non-prosecution.

The Supreme Court holds AORs to high standards of diligence and promptness. You’re expected to maintain systems for tracking hearing dates, compliance deadlines, and pending matters to ensure nothing falls through the cracks.

Many successful AORs employ registered clerks and use case management software to handle this responsibility systematically.

Essential Skills to Become an AOR

Supreme Court Rules and Procedure Expertise

Mastering the Supreme Court Rules, 2013, is non-negotiable for AOR practice. These rules govern every aspect of Supreme Court procedure, from how petitions must be formatted to what documents must accompany different types of applications.

You need to know provisions on court fees, limitation periods, service of notices, interim applications, review petitions, and curative petitions inside out. The AOR examination tests this knowledge extensively, and your daily practice will constantly draw on it.

Beyond the written rules, there are unwritten conventions and Registry practices that you’ll learn during your training year.

Understanding how the Registry processes documents, what objections they commonly raise, and how to resolve procedural issues efficiently makes you effective as an AOR.

Senior AORs often say that procedural expertise is what separates competent AORs from struggling ones; substantive legal knowledge is important, but procedural fluency is what actually gets cases through the Supreme Court system smoothly.

Constitutional Law Depth and Case Knowledge

The Supreme Court predominantly deals with constitutional questions, public law matters, and cases involving substantial questions of law.

As an AOR, you need a strong grounding in constitutional law, fundamental rights jurisprudence, federalism principles, judicial review doctrines, and interpretive methodologies.

Even if you specialize in a specific area like taxation or commercial law, many Supreme Court matters involve constitutional dimensions that you must navigate competently.

You also need to maintain current awareness of Supreme Court judgments and evolving legal principles. The Court’s decisions shape law across India, and what the Supreme Court says today becomes binding precedent for tomorrow’s cases.

Reading recent judgments, understanding how different benches approach similar issues, and tracking doctrinal developments are essential for effective Supreme Court practice.

The fourth paper of the AOR examination tests your knowledge of leading cases, reflecting how central case law familiarity is to the AOR role.

Drafting as per Supreme Court Standards

Supreme Court drafting has distinct conventions that differ from High Court or trial court pleadings.

Special Leave Petitions must have a concise synopsis summarizing the grounds of appeal, a proper statement of facts with paragraph wise narratives, a clear articulation of substantial questions of law, and an appropriate citation of binding precedents.

Your drafts must be legally sound, factually accurate, procedurally compliant, and persuasive without being verbose. The AOR examination’s second paper on drafting tests your ability to produce Supreme Court standard documents under time pressure.

Good drafting isn’t just about legal argumentation; it’s also about format and presentation. Supreme Court Registry maintains strict standards for document pagination, indexing, certification, and compilation.

Learning to prepare “paper books” (the compiled set of documents filed with petitions) according to Supreme Court conventions is a practical skill you’ll develop during training.

Many petitions face Registry objections not because of substantive defects but because of formatting or compilation errors. Your drafting skills must encompass both legal substance and procedural form.

Oral Advocacy Excellence

While AORs often brief senior advocates for complex oral arguments, you should develop your own advocacy skills for regular matters.

Supreme Court advocacy requires brevity, clarity, responsiveness to judicial queries, and respect for Court time.

Judges appreciate advocates who can state their case succinctly, respond directly to questions without evasion, acknowledge contrary precedents honestly, and assist the Court in reaching the right conclusion. Effective Supreme Court advocacy is less about theatrical oratory and more about precise legal analysis presented clearly.

You’ll also need to master the art of mentioning matters for urgent listing, making oral applications for interim relief, and seeking short adjournments when necessary.

These routine oral interactions before the Court may seem minor, but they require confidence, clarity, and adherence to Court etiquette.

Your training year provides opportunities to observe senior advocates and your training AOR in action, learning through observation how effective Supreme Court advocacy actually works.

Many AORs find that their advocacy improves significantly through regular Supreme Court practice; the high standards of the Court push you to constantly refine your skills.

Conclusion

Understanding the AOR full form, Advocate on Record, opens a window into how India’s Supreme Court maintains quality control and procedural discipline in the apex court of the world’s largest democracy.

The AOR designation isn’t just a professional credential; it’s a constitutional framework ensuring that only properly trained and qualified advocates can represent parties before India’s highest judicial authority.

From the exclusive filing rights that distinguish AORs from regular advocates to the rigorous qualification pathway involving four years of practice, specialized training, and a challenging examination, every aspect of the AOR system serves to uphold standards at the Supreme Court level.

For law students, practicing advocates, or anyone interested in India’s legal system, grasping what AOR means helps you understand Supreme Court practice dynamics.

Whether you’re considering pursuing this qualification yourself or simply want to appreciate how India’s judiciary functions at its highest level, the AOR full form represents an important piece of legal infrastructure.

If you’re interested in exploring the detailed pathway to becoming an AOR, including comprehensive guidance on training, examination preparation, and registration processes, I recommend reading my article on the complete AOR career roadmap for 2026 for step-by-step guidance on this prestigious legal qualification.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the AOR Full Form?

AOR stands for Advocate on Record, a special designation for advocates authorized under Supreme Court Rules, 2013, to practice before the Supreme Court of India. Only AORs can file cases and represent clients independently in the Supreme Court.

Who can become an Advocate on Record?

Any advocate enrolled with a State Bar Council who has completed four years of practice, undergone one year of training under a senior AOR, and passed the Supreme Court’s AOR examination can become an Advocate on Record.

Is AOR the same as a regular advocate?

No, AOR is a specialized designation. Regular advocates can practice in lower courts and High Courts, but only AORs have exclusive rights to file cases in the Supreme Court. There are approximately 15 to 20 lakh regular advocates in India versus only 3,789 registered AORs.

How many years does it take to become an AOR?

The minimum timeline is approximately 6 years from initial Bar Council enrollment: 4 years of general practice + 1 year of AOR training + appearing for the examination and completing registration (typically another year).

Can AOR practice in High Courts and lower courts?

Yes, AORs retain all rights of regular advocates and can practice in any court in India. The AOR designation adds Supreme Court practice rights without removing other practice privileges.

What is the difference between AOR and Senior Advocate?

AOR is a qualification that gives you the right to file cases in the Supreme Court. Senior Advocate is a designation of excellence given to distinguished advocates for their expertise. Interestingly, Senior Advocates cannot become AORs, they must be briefed by AORs to appear in the Supreme Court.

How many Advocates on Record are there in India?

As of 2025, there are approximately 3,789 registered Advocates on Record with the Supreme Court of India, making it one of the most exclusive professional designations in Indian law.

Is the AOR designation valid for lifetime?

Yes, once registered as an AOR, the designation remains valid for your entire professional career unless revoked due to professional misconduct, conviction for offenses involving moral turpitude, or contempt of court. You don’t need to renew the registration periodically.

Can foreign lawyers become AORs in India?

No, foreign lawyers cannot become AORs. The AOR system requires enrollment with an Indian State Bar Council, which is only available to Indian citizens who have completed law degrees from Indian universities recognized by the Bar Council of India.

What is the salary of an Advocate on Record?

An AOR typically earns approximately ₹60,000-90,000 per case, including drafting, filing, and first appearance. This breaks down into ₹20,000-25,000 for drafting, ₹10,000-15,000 for filing and vakalatnama signing, and ₹30,000-50,000 per appearance. Complex cases can generate ₹1-2 lakh total through multiple hearings and premium rates.

Is the AOR exam difficult?

Yes, the AOR examination is challenging, with a historical pass rate of approximately 19-24%. You must score at least 50% in each of four papers individually and 60% aggregate across all papers. The exam tests Supreme Court procedures, drafting skills, professional ethics, and knowledge of leading cases comprehensively.

Where can I find the list of registered AORs?

The Supreme Court of India maintains an official list of all registered Advocates on Record on its website at www.sci.gov.in under the “Advocate on Record” section. The list includes AOR names, codes, and contact information, and is updated regularly as new AORs are registered.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications