Understand bail types, CrPC provisions and BNSS 2023 changes, constitutional rights, court powers, landmark judgments, and conditions. Know your rights when facing arrest.

Table of Contents

What is bail?

Bail represents one of the most fundamental protections in India’s criminal justice system. When you’re accused of a crime, bail is the legal mechanism that allows you to remain free during investigation or trial instead of being held in custody. It’s essentially a conditional release that balances your right to personal liberty with the need to ensure you appear in court when required.

The concept operates on a simple promise: you’ll be released from police or judicial custody if you provide assurance; often through a monetary bond or personal guarantee that you’ll attend all court proceedings. This assurance can come from you directly (personal bond) or from others who vouch for you (sureties).

Think of bail as the bridge between arrest and trial. Without it, you’d remain in jail for months or even years while your case proceeds through India’s overburdened court system. This would be fundamentally unjust, as you’re presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Definition of Bail under the Indian Law

The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) 1973 did not explicitly define “bail.” However, the BNSS 2023 has introduced formal definitions for related terms in Section 2(1)(b), which defines bail as “the release of a person from custody upon execution of a bond.”

Section 2(1)(d) of BNSS defines a bail bond as “an undertaking to appear before the court or investigating officer as directed.” These definitions, though seemingly simple, carry profound legal implications. They establish that bail is fundamentally about ensuring your presence, not punishing you before conviction.

Black’s Law Dictionary defines bail as “to procure the release of a person from legal custody, by undertaking that he/she shall appear at the time and place designated and submit him/herself to the jurisdiction and judgment of the court“. Indian courts have consistently interpreted bail through this lens, viewing it as a conditional liberty rather than absolute freedom.

The legal framework for bail spans several provisions. The CrPC contains sections 436 to 450 dealing with bail and bonds, now corresponding to Sections 478 to 490 in the BNSS 2023. These provisions create a comprehensive system governing when bail can be granted, who can grant it, and under what conditions.

Purpose of Bail

The primary purpose of bail is to secure your attendance at trial while respecting your fundamental right to liberty. Article 21 of the Indian Constitution guarantees the right to life and personal liberty, and bail ensures that an individual’s liberty is not arbitrarily curtailed without due process.

Bail serves multiple critical functions in our justice system. First, it prevents pre-trial punishment. You haven’t been convicted yet, so you shouldn’t suffer the consequences of imprisonment simply because you’ve been accused. The presumption of innocence; a cornerstone of criminal law demands that you’re treated as innocent until the court proves otherwise.

Second, bail protects you from the devastating personal consequences of prolonged detention. Imagine losing your job, missing your children’s important moments, or being unable to care for elderly parents; all while your innocence remains undetermined. Bail prevents these catastrophic disruptions to your life and family.

Third, bail serves practical purposes for you as the accused. Being out on bail allows you to actively participate in your own legal defense, consult with your lawyer, gather evidence, and ensure your presence in court proceedings. You can’t effectively defend yourself from inside a jail cell.

Fourth, bail addresses systemic concerns. India’s prisons are notoriously overcrowded, with a significant portion of inmates being undertrials. Bail provides a mechanism to reduce the burden on the prison system while ensuring judicial efficiency. Without bail, our already strained prison infrastructure would collapse entirely.

Finally, bail reflects the fundamental balance our legal system must strike: your individual liberty versus public safety. Courts must weigh whether releasing you poses risks: like fleeing prosecution, tampering with evidence, or threatening witnesses against your constitutional right to freedom. This delicate balance is at the heart of every bail decision.

Types of Bail in India

Understanding the different types of bail available is crucial when you’re facing criminal charges. Each type serves a specific purpose and applies in different circumstances. Let me walk you through each one so you know exactly what to pursue in your situation.

Regular Bail

What is Regular Bail?

Regular bail is what most people think of when they hear “bail.” It’s the release from custody that you seek after you’ve already been arrested and are in police or judicial custody. Regular bail is granted under Sections 437 and 439 of the CrPC, now corresponding to Sections 480 and 483 of the BNSS, and is applicable when an individual is arrested for a cognizable offence. The process differs significantly depending on whether your offence is classified as “bailable” or “non-bailable”; a distinction I’ll explain shortly.

For bailable offences, regular bail is your absolute right. The police or court cannot refuse it. You simply need to furnish the required bond, and you must be released. For non-bailable offences, however, regular bail becomes discretionary; the court decides whether to grant it based on various factors.

When to Apply for Regular Bail?

You should apply for regular bail immediately after arrest if you’re charged with a bailable offence. Don’t wait, time matters. When a person is detained on suspicion of committing a bailable offence, bail becomes a right, and the person may be released in accordance with the procedures outlined in Section 436 CrPC/Section 478 BNSS.

For non-bailable offences, timing becomes more strategic. You can apply for regular bail at any stage of the proceedings; during investigation, after a chargesheet is filed, during trial, or even during the appellate process. However, I recommend applying as soon as possible after arrest, as prolonged detention weakens your position.

If you’ve been arrested without a warrant and the police haven’t completed their investigation within 24 hours, you must be produced before a Magistrate. This is your first opportunity to seek bail formally. Don’t miss this critical window.

Consider applying for regular bail when: (1) you’ve been arrested and are in custody, (2) the investigation is taking longer than expected, (3) you have strong grounds showing you won’t flee or tamper with evidence, or (4) you fall under special categories like women, children under 16, or sick/infirm accused (where bail is more readily granted even in non-bailable cases).

Which Courts Can Grant Regular Bail?

The power to grant regular bail is distributed across different courts based on the severity of the offence and the stage of proceedings. Understanding which court to approach can save you valuable time.

For Bailable Offences: If an individual is accused of a bailable offence, the police or the court is obligated to release the individual on bail upon furnishing a bail bond. Even the police officer in charge of the station can grant you bail in bailable cases. You don’t necessarily need to approach a court immediately.

For Non-Bailable Offences – Magistrate’s Powers: Under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, Magistrate Courts have the power to grant bail in non-bailable offences, but with limitations. Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS empowers the court and the officer-in-charge of the police station to determine whether or not to grant bail in non-bailable offences.

However, if you’re accused of an offence punishable by death or life imprisonment, and the Magistrate has reasonable grounds to believe you’re guilty, they cannot grant bail. In such serious cases, you’ll need to approach higher courts.

For Non-Bailable Offences – High Court and Sessions Court Powers: Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS empowers the High Court or Sessions Court to grant bail even in cases of offences punishable by death or life imprisonment. These superior courts have wider discretionary powers and can grant bail even where Magistrates cannot.

The High Court and Sessions Court also have concurrent jurisdiction; meaning you can approach either one. However, as a practical matter, you should typically approach the Sessions Court first. If the Sessions Court denies your bail, you can then appeal to the High Court. Approaching the High Court directly may not always be strategic, though it’s legally permissible.

Anticipatory Bail

What is Anticipatory Bail?

Anticipatory bail is a unique and powerful protection available in Indian law. Unlike regular bail (which you seek after arrest), as per Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS anticipatory bail is sought before arrest when you reasonably believe you might be arrested for a non-bailable offence. Think of it as pre-emptive protection; a judicial directive stating that if police do arrest you, you must be released on bail immediately.

Anticipatory bail acknowledges that the mere threat of arrest can be devastating. Once arrested, even if you’re innocent, the stigma attaches. Your reputation suffers, your employment may be jeopardized, and your family faces social humiliation. Anticipatory bail prevents this harm by ensuring you’re never taken into custody in the first place (or if you are, you’re released immediately).

When Can You Apply for Anticipatory Bail?

You can apply for anticipatory bail when you have a reasonable apprehension that you may be arrested for a non-bailable offence. But what constitutes “reasonable apprehension”? Courts have interpreted this broadly.

You might have reasonable grounds to fear arrest if: (1) an FIR has been registered naming you as an accused in a non-bailable offence, (2) you’ve received information that police are looking for you, (3) a complaint has been filed against you and police investigation has commenced, or (4) there’s credible information that someone plans to implicate you falsely in a criminal case.

Some situations where anticipatory bail becomes essential: (1) matrimonial disputes where your spouse has filed a complaint under dowry harassment laws, (2) business disputes where commercial rivals file false criminal complaints, (3) politically motivated cases, (4) cases involving Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act where anticipatory bail was restricted (though courts may still grant it in exceptional circumstances), or (5) any situation where you fear false implication.

Which Courts Can Grant Anticipatory Bail?

Unlike regular bail, which can be granted by Magistrate Courts, anticipatory bail can only be granted by superior courts. The individual can apply for anticipatory bail directly to the High Court or the Court of Session.

You have two options: (1) the Sessions Court having jurisdiction over the area where the offence allegedly occurred, or (2) the High Court. Both courts have concurrent jurisdiction for anticipatory bail, meaning you can approach either one.

As a practical strategy, most lawyers recommend approaching the Sessions Court first. Sessions Courts are generally more accessible, less formal, and dispose of matters relatively quickly. If your application is rejected by the Sessions Court, you can then approach the High Court with a fresh application or an appeal. However, in urgent situations or when dealing with particularly serious allegations, approaching the High Court directly might be advisable. The High Court’s orders often carry more weight, and in sensitive cases, this can provide better protection.

Duration and Validity of Anticipatory Bail

This is where anticipatory bail becomes particularly valuable. The Supreme Court, in Sushila Agarwal and others v. State (NCT of Delhi) and Others (AIR 2020 SUPREME COURT 831), clarified that anticipatory bail, once granted, generally remains in effect until the very end of the trial.

However, understand that anticipatory bail can be cancelled if you violate any conditions imposed by the court.

Interim Bail: Temporary Relief

What is Interim Bail?

Interim bail is a temporary, short-term release granted while your main bail application (whether regular bail or anticipatory bail) is pending before the court. Interim bail is a temporary form of release granted to individuals during the pendency of an application for anticipatory or regular bail, providing them a brief respite from custody.

Although not expressly defined under the CrPC/BNSS, interim bail has evolved through judicial pronouncements and derives its legal foundation from Article 21 and Article 226 of the Constitution.

Think of it as a stop-gap arrangement. When you file a bail application, the court might not decide immediately; it may need time to review the case diary, hear the prosecution’s objections, or study the evidence. During this waiting period, you’d normally remain in custody. Interim bail prevents this by allowing you temporary freedom until the court makes its final decision.

Interim bail is issued as per the requirements of the case. The interim bail time can be prolonged, but if the accused person fails to pay the court for confirmation and/or continuation of the interim bail, his freedom will be lost.

When is Interim Bail Granted?

Courts grant interim bail in specific circumstances where immediate relief is necessary to prevent irreparable harm. Let me explain the main situations where interim bail becomes crucial.

Medical Emergencies: If the accused has a serious illness that requires urgent or specialized treatment, the court may grant interim bail to facilitate necessary medical care. If you’re suffering from a condition that cannot be adequately treated in prison or if remaining in custody poses serious health risks, interim bail becomes appropriate.

Humanitarian Grounds: Courts consider your personal circumstances. If the accused is the sole breadwinner or caregiver for dependents, the court may consider granting interim bail to prevent undue hardship on their family. If your family depends entirely on you for survival, or if you need to care for elderly parents or young children, these factors may convince the court to grant interim bail.

Investigation Delays: If the investigation is taking an unreasonably long time despite the accused’s cooperation, interim bail may be granted to prevent prolonged detention without a clear cause. When police or investigating agencies are dragging their feet without justification, you shouldn’t suffer unnecessarily in custody.

Pending Bail Hearing: When your regular or anticipatory bail application is scheduled for hearing but the date is weeks away, the court may grant interim bail to prevent you from languishing in custody during this waiting period. This is particularly common when courts are overburdened and hearing dates are delayed.

Reputation Protection: The Supreme Court concluded that the authority of the courts to give interim relief is inherent in their power to grant bail, and interim bail is significant because an accused may risk arrest even before the verdict on his bail is issued. Courts recognize that your reputation is a valuable asset—being jailed even briefly can cause irreparable damage to your standing in society.

Legal Basis and Court Powers for Interim Bail

Here’s something important to understand: The Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) and now the BNSS do not explicitly define interim bail, but courts have the legal framework that allows them to grant such relief.

Courts derive the power to grant interim bail from their general bail provisions. The interim bail meaning is understood within the context of specific provisions, including Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, which addresses bail in non-bailable cases and empowers Magistrates to grant bail under certain conditions.

The High Court and Sessions Court derive their power from Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS, which gives them special powers regarding bail. These courts can grant interim bail while considering the main bail application.

Magistrate Courts can also grant interim bail in appropriate cases under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, particularly when the final bail hearing needs to be scheduled later due to court workload or need for additional submissions.

Default Bail (Statutory Bail)

What is Default Bail and Why Is It Important?

Default bail codified under section 167 CrPC/Section 187 BNSS, also called statutory bail, is perhaps the most powerful type of bail available to you. Why? Because it’s an absolute, indefeasible right. Default bail is a significant right available to an accused person under Indian law that arises from the failure of law enforcement agencies to complete their investigation (i.e., filing of chargesheet) within a prescribed time limit.

Let me explain what makes default bail so significant. Unlike regular bail or anticipatory bail where the court exercises discretion, default bail is automatic. You don’t need to prove you won’t flee or tamper with evidence. You don’t need to show you’re innocent. The law simply says: if police haven’t filed the chargesheet within the time limit, you must be released on bail. No ifs, no buts as held in a landmark judgment of the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Hitendra Vishnu Thakur vs. State of Maharashtra (AIR 1994 SC 2623)

Why did the law create this automatic right? To prevent indefinite detention without charges. Imagine being arrested and then sitting in jail for months or even years, while police “investigate.” Without the default bail provision, investigating agencies could keep you in custody indefinitely by simply not filing the chargesheet. This would be a gross violation of your right to liberty and speedy trial.

Time Limit: 60 vs. 90 days rules

The magic numbers in default bail are 60 and 90 days. These represent the maximum periods for which you can be detained during investigation before the chargesheet must be filed. If police exceed these limits, your right to default bail kicks in automatically.

Here’s how the time limits work:

60 Days Rule: For offences punishable with imprisonment for a term less than ten years, the investigation must be completed within 60 days. This applies to the majority of criminal offences. If you’re accused of theft, cheating, assault, or most other common crimes (where maximum punishment is below 10 years), the 60-day rule applies.

90 Days Rule: For offences punishable with death, life imprisonment, or imprisonment for a term of not less than ten years, the period is 90 days. This longer period applies to the most serious crimes—murder, rape, dacoity, terrorism-related offences, and other grave crimes carrying death penalty, life imprisonment, or 10+ years imprisonment.

Let me be very clear about what these periods mean. They’re not suggestions or guidelines; they’re absolute limits. When the clock runs out, your right to default bail becomes indefeasible (cannot be taken away).

How to calculate the period

Calculating the 60/90 day period correctly is crucial; getting this wrong could mean you miss your chance for default bail. Let me walk you through the calculation carefully.

Starting Point: The time limit for filing the charge sheet begins on the day the accused is detained for the first time. Count from the day of your first arrest or remand, not from when the FIR was registered or when investigation began.

What Happens During These 60/90 Days: After your arrest, if the investigation cannot be completed within 24 hours, you must be produced before a Magistrate. The Magistrate can authorize your detention (remand) for up to 15 days initially. This can be extended by further 15-day periods, but the total detention during investigation cannot exceed 60 or 90 days (depending on the offence category).

When Does the Right Accrue? Your right to default bail accrues at the completion of the 60th or 90th day (as applicable) if no chargesheet has been filed. If the investigation is not completed within these periods, the accused is entitled to be released on bail, provided they furnish bail.

Practical Calculation Example: Let’s say you were arrested and first remanded to judicial custody on January 1st, and you’re accused of an offence punishable with 5 years imprisonment (60-day category). Count 60 days from January 1st. If no chargesheet is filed by March 1st (the 60th day), you’re entitled to default bail starting March 2nd. Apply immediately.

Bailable vs. Non-Bailable Offences

Understanding whether your offence is bailable or non-bailable is fundamental; it determines whether bail is your absolute right or subject to judicial discretion. This classification affects everything: whether police can grant you bail, how quickly you can be released, and what arguments you’ll need to make in court.

What Are Bailable Offences?

A bailable offence is one where bail is your absolute right; neither police nor courts can refuse it if you fulfill the basic requirements. An offence that is categorised as bailable is referred to as a bailable offence. In the event of such an offence, bail can be awarded as a matter of law under Section 436 CrPC/Section 478 BNSS when such prerequisites have been satisfied.

In bailable offences, you don’t need to convince anyone that you deserve bail. You don’t need to prove you won’t flee or that you’re innocent. The law simply says: if you’re accused of a bailable offence, you must be released on bail when you furnish the required bond. It’s that straightforward.

A crime is considered a bailable offence if the maximum sentence is three years. Generally, bailable offences are less serious crimes where the punishment is relatively minor. Examples include simple assault, defamation, public nuisance, simple hurt, and many property offences involving small amounts.

What Are Non-Bailable Offences?

A non-bailable offence is one in which bail cannot be granted as a matter of right unless ordered by a competent court. In such instances, the accused may seek bail under Sections 437 BNSS/Section 439 CrPC. These are serious offences such as murder, dacoity, dowry death, rape; where the punishment is typically three years or more

How to Determine If Your Offence is Bailable or Non-Bailable?

Check the First Schedule of the CrPC or BNSS, which lists all offences and their classifications. The schedule clearly marks whether each offence is bailable or non-bailable, cognizable or non-cognizable. Your lawyer can quickly determine this, or you can check online legal databases that provide offence classifications.

Bail Conditions Under CrPC/BNSS

When a court grants you bail, freedom doesn’t come without strings attached. Courts impose specific conditions that you must strictly comply with. Understanding these conditions is crucial: violating them can result in immediate bail cancellation and re-arrest. Let me walk you through what courts typically require and what happens if you fail to comply.

Standard Bail Conditions Imposed by Courts

Conditions Under Section 437(3) CrPC / Section 480(3) BNSS

When granting bail in non-bailable offences, courts exercise their power under Section 437(3) CrPC / Section 480(3) BNSS to impose various conditions. These aren’t arbitrary; they’re designed to ensure you don’t abuse your freedom while on bail.

Personal Bond with or Without Sureties

The foundation of every bail is the bond; a written guarantee that you’ll appear in court when required. A person released on bail must provide a bond, with or without sureties, as ordered by the court. Courts have discretion to decide whether you need sureties (guarantors) or can be released on a personal bond alone.

A personal bond without sureties means you alone guarantee your appearance. You sign a bond promising to attend court proceedings and agreeing to forfeit a specified sum to the government if you fail to appear. This is typically granted when courts are satisfied you’re reliable or when you cannot arrange sureties due to poverty or social circumstances.

A surety bond requires one or more people (sureties) to vouch for you. Sureties are essentially guarantors for the accused, ensuring their appearance in court and compliance with the bail conditions. The surety must possess the means to pay the bail amount if the accused fails to appear in court. If you abscond, your sureties become liable to pay the bond amount to the government.

No Similar Offences While on Bail

This fundamental bail condition prohibits you from engaging in any criminal activity similar to the charges you’re facing while on bail. The court grants you freedom based on trust that you won’t misuse it or pose a danger to society. Violating this condition by committing a similar offence will result in immediate cancellation of your bail and demonstrates you’re a repeat offender who cannot be trusted. This breach will also make it extremely difficult to obtain bail in future cases.

No Tampering with Evidence or Witnesses

This condition is fundamental and appears in virtually every bail order. You’re strictly prohibited from tampering with, destroying, or concealing any evidence relevant to your case. You cannot directly or indirectly threaten, induce, or promise witnesses to discourage them from testifying or disclosing facts to the court or police.

What constitutes “tampering”? It includes destroying physical evidence, deleting digital records, pressuring witnesses to change their statements, offering bribes, making threats, or attempting to influence the investigation or trial in any way. Even indirect influence through family members or associates violates this condition.

Other conditions which the court may impose

Surrender of Passport

If you hold a passport, courts almost always require its surrender to prevent you from fleeing the country. You must deposit your passport with the court or investigating officer immediately after bail is granted. This condition is non-negotiable in serious cases; courts need assurance you won’t escape prosecution by leaving India.

If you need to travel abroad for genuine reasons (medical emergency, business obligations, family crisis), you must apply to the court for temporary return of your passport with a detailed explanation and supporting documents. Courts may grant permission in exceptional circumstances but will impose strict timelines and may require additional bonds.

Regular Reporting to Police Station

One of the most common conditions is regular reporting to the local police station. Regular police station reporting ensures you remain within reach and haven’t absconded. Courts typically order you to report to the nearest police station or the investigating officer’s station every week or month.

When you report, you must sign a register maintained by the police. This creates a record of your compliance. Missing even a single reporting date can be grounds for bail cancellation, so maintain strict regularity. If you’re genuinely unable to report due to a medical emergency or other unavoidable circumstances, inform the police in advance and obtain written acknowledgment.

Prohibition on Leaving Jurisdiction Without Permission

Courts restrict your movement to ensure you remain available for trial. Most bail orders require you to stay within the court’s jurisdiction unless prior permission is obtained for travel. You cannot leave the district or state without court permission.

If you need to travel; whether for work, medical treatment, or family emergencies; you must file an application in court explaining the necessity, providing supporting documents, and specifying exact travel dates. Courts generally permit short-term travel for legitimate reasons but require you to provide contact information and may mandate reporting at your destination.

Mandatory Court Appearances

Perhaps the most critical condition: you must appear in court on every date scheduled for your case. Failure to appear in court is the fastest way to get your bail cancelled. Courts view non-appearance extremely seriously because the entire bail system depends on this trust.

Mark every court date carefully. Arrive early. If you’re genuinely unable to attend due to serious illness or unavoidable circumstances, your lawyer must inform the court in advance and seek adjournment with supporting documents (medical certificates, etc.). Never simply fail to appear; this guarantees bail cancellation and a non-bailable warrant for your arrest.

Section 441 CrPC / Section 485 BNSS: Bond Requirements

What is a Bail Bond?

A bail bond is a formal legal document; a written undertaking you provide to the court guaranteeing your appearance at all stages of the criminal proceedings. A bail bond is a legal instrument requiring a monetary or property deposit as a guarantee for the accused’s appearance in court.

Think of it as a contract between you and the court. You promise to appear whenever required, and in exchange, the court releases you from custody. If you break this promise by absconding or failing to appear, you forfeit the bond amount and face immediate re-arrest.

The bond specifies several critical elements: (1) the amount you or your sureties will forfeit if you don’t appear, (2) the conditions you must comply with, (3) the names and details of any sureties, (4) the case details and charges against you, and (5) your acknowledgment that you understand the consequences of non-compliance.

Types of Bonds: Personal vs Surety

Indian law recognizes different types of bonds depending on your circumstances and what the court orders:

Personal Bond: The accused gives a written promise to appear in court without requiring monetary or surety guarantees. You sign a document promising to attend all proceedings and agreeing to forfeit a specified sum if you fail. No one else is involved, you alone guarantee your appearance. Courts grant personal bonds when they’re satisfied of your reliability or when requiring sureties would cause undue hardship.

Surety Bond: A third party (surety) provides a guarantee that the accused will comply with bail conditions. The surety undertakes the financial risk if the accused absconds. One or more people vouch for you by signing the bond. They promise to produce you in court and agree to pay the bond amount if you abscond. Sureties must demonstrate financial capability; courts verify their income, property ownership, and creditworthiness before accepting them.

Who can be your surety? Courts prefer property owners or people with stable income and established roots in the community. Your sureties could be family members, friends, employers, or even professional sureties (though courts scrutinize professional sureties carefully for potential abuse).

Cash Bond: The accused deposits a specified sum of money with the court as a bail bond. You pay actual money to the court which is held as security. If you comply with all conditions and attend all proceedings, the money is refunded after the case concludes.

Property Bond: Immovable property is pledged as collateral. You or your sureties pledge land, houses, or other immovable property to secure your release. The property must be verified by court officials, and its value must meet or exceed the bond amount.

Bail Condition Violations and Consequences

Cancellation of Bail

When you violate bail conditions, courts can cancel your bail and send you back to custody. The CrPC provides that the accused, public prosecutor, complainant, or any other aggrieved person may use the power to terminate or cancel the bail. Along with it, the High Court, Court of Session, and various lower courts, including Magistrates, have the authority to cancel previously granted bail.

Section 437(5) CrPC/Section 480(5) BNSS empowers Magistrate Courts to cancel bail granted by them. Section 483 (3) BNSS/Section 439(2) CrPC gives the High Court and Sessions Court power to cancel bail granted by any court, including their own bail orders. This means if a Magistrate grants you bail and you violate conditions, the prosecution can approach the Sessions Court or High Court directly for cancellation.

Grounds for bail cancellation include: (1) absconding or failing to appear in court, (2) tampering with evidence or threatening witnesses, (3) committing a new offence while on bail, (4) violating travel restrictions or leaving the jurisdiction without permission, (5) failing to report to police as ordered, (6) attempting to influence the investigation or trial, or (7) any other material breach of bail conditions.

Re-arrest and Remand to Custody

Once bail is cancelled, the consequences are immediate and severe. The court will issue a non-bailable warrant for your arrest. Police will execute the warrant, arrest you, and produce you before the court. You’ll then be remanded to judicial custody and must remain in jail throughout the trial unless you secure fresh bail; which becomes significantly harder after cancellation.

When applying for fresh bail after cancellation, you’ll need to explain the violation, show it wasn’t willful or malicious, demonstrate changed circumstances, and provide stronger assurances of compliance.

Bond Forfeiture

When you or your sureties signed the bail bond, you agreed to forfeit the bond amount if you breach conditions as per Section 446 CrPC/Section 491 BNSS. If the accused fails to surrender at the appointed time, it results in forfeiture of the security. The court will order you and your sureties to pay the forfeited amount to the government.

For your sureties, this is catastrophic. They vouched for you, and your violation means they lose the money or property they pledged. Courts can attach and sell their property to recover the bond amount.

Your Rights: Constitutional Protection

Even while navigating the bail process, never forget that you have fundamental constitutional rights that protect you. These aren’t mere legal technicalities: they’re the bedrock principles that define India as a constitutional democracy. Understanding these rights empowers you to demand fair treatment.

Article 21: Right to Life and Personal Liberty

Article 21 states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” Courts have interpreted this expansively to mean that the procedure must be fair, just, and reasonable; not arbitrary or oppressive.

In the case of Babu Singh And Ors vs. the State of U.P (AIR 1978 SC 527), it was held that the right to bail comes under Article 21 of the Indian Constitution and its scope. Your right to seek bail isn’t a mere statutory privilege; it’s a constitutional right that cannot be taken away without proper legal procedure.

What does this mean practically? It means bail cannot be denied arbitrarily or whimsically. Courts must provide reasoned decisions. Your detention must be justified. The state must show why your liberty should be curtailed. You don’t have to prove your innocence to get bail; the burden is on the prosecution to show why bail should be denied.

Presumption of Innocence Until Proven Guilty

One of the most fundamental principles in criminal law: you’re presumed innocent until the state proves your guilt beyond reasonable doubt as held by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Dataram Singh vs. The State of Uttar Pradesh [2018 (3) SCC 22]. The concept of bail plays the role of check and balance; it ensures that the person accused is treated as innocent until proven guilty for the offence.

This principle has profound implications for bail. If you’re presumed innocent, why should you be jailed before trial? Pre-trial detention becomes punishment before conviction; fundamentally unjust. Bail protects you from this injustice by ensuring you’re not treated as guilty until you’ve actually been convicted.

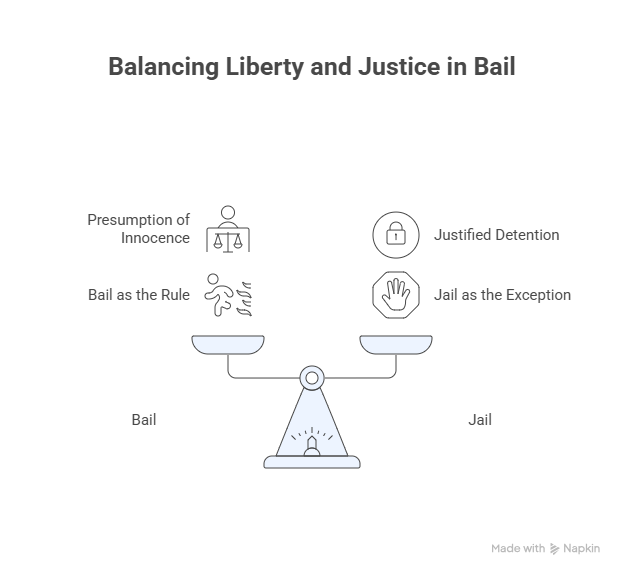

“Bail is the Rule, Jail is the Exception” – Foundational Principle

What does “bail is the rule, jail is the exception” mean? It means the starting point is always your liberty. Bail should be granted unless there are compelling reasons to deny it. Detention is the exception that requires justification; not the other way around.

This principle doesn’t mean everyone gets bail automatically. Courts still consider factors like flight risk, evidence tampering risk, and potential danger to society. But these considerations must be genuine and evidence-based; not hypothetical or speculative. The default position is always in favor of your liberty.

This is perhaps the single most important principle in Indian bail jurisprudence. In State of Rajasthan v. Balchand (1977 AIR 2447) and Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation [(2021) 10 SCC 773], the Supreme Court emphasized that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception.” The Court emphasized the importance of personal liberty and ruled that bail should be granted in cases where the accused is not likely to abscond or tamper with evidence.

Landmark Supreme Court Judgments on Bail

The Supreme Court of India has, through decades of judgments, shaped bail jurisprudence into what it is today. These landmark cases aren’t just legal citations; they’re powerful declarations of your rights and limitations on state power. Understanding these judgments helps you appreciate the legal foundation supporting your bail application.

State of Rajasthan vs Balchand (1977): “Bail is the Rule, Jail is the Exception”

Key Legal Principles Established

The Balchand judgment is the cornerstone of modern bail law in India. In State of Rajasthan v. Balchand (1977 AIR 2447), the Supreme Court established the principle that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception.”

Justice Krishna Iyer, writing for the Court, emphasized several critical principles. First, personal liberty is precious and should not be lightly curtailed. Second, detention before conviction is an affront to human dignity and should be the exception, not the norm. Third, courts must presumptively favor bail unless compelling reasons exist to deny it.

The judgment established that refusing bail requires justification; granting bail doesn’t. This reversed the earlier mindset where accused persons had to convince courts why they deserved liberty. Now, prosecutors must convince courts why liberty should be denied.

Impact on Bail Jurisprudence in India

Balchand’s impact cannot be overstated. It transformed bail from a discretionary privilege into a presumptive right. The Hon’ble Supreme Court emphasized the importance of personal liberty and ruled that bail should be granted in cases where the accused is not likely to abscond or tamper with evidence.

Post-Balchand, courts must actively consider bail favorably rather than looking for reasons to deny it. The judgment has been cited in thousands of subsequent cases and remains the first authority lawyers cite in bail applications. It represents a fundamental shift toward protecting individual liberty against state power.

Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia vs State of Punjab (1980): Scope of Anticipatory Bail

Liberal Interpretation of Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS

The Sibbia judgment is the leading authority on anticipatory bail. In Gurbaksh Singh Sibbia v. State of Punjab [1980 AIR 1632], the Supreme Court clarified the scope of anticipatory bail, stating it is a safeguard against arbitrary detention.

The Court held that Section 482 BNSS/Section 438 CrPC should be interpreted liberally, not restrictively. Courts cannot refuse anticipatory bail merely because the offence is serious or because the applicant might be guilty. The provision exists precisely to protect people from harassment through the process of arrest itself.

Justice Krishna Iyer wrote that anticipatory bail serves a vital purpose: preventing the humiliation, stigma, and disruption caused by arrest and custody. Even if you’re eventually acquitted, the damage from arrest; to your reputation, employment, and family; may be irreparable. Anticipatory bail prevents this harm.

Guidelines for Granting Anticipatory Bail

The Sibbia judgment established comprehensive guidelines courts must follow when considering anticipatory bail. Courts should consider: (1) the nature and seriousness of the proposed charge, (2) the applicant’s character, means, and standing, (3) the likelihood of the applicant fleeing justice, (4) whether the charge is prima facie false or motivated by malice.

Importantly, the Court held that anticipatory bail can be granted even after an FIR is registered. Many lower courts had been refusing anticipatory bail once an FIR was filed, reasoning that the “apprehension of arrest” was no longer prospective but actual. Sibbia clarified this was wrong, as long as you haven’t been arrested yet, you can seek anticipatory bail.

Hussainara Khatoon vs State of Bihar (1979): Right to Speedy Trial

Undertrial Prisoners’ Rights

The Hussainara Khatoon case series represents a watershed moment in Indian criminal justice. In Hussainaira Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar (1979 AIR 1369), the Supreme Court highlighted the plight of undertrials languishing in jail due to their inability to afford bail, emphasizing the need for speedy trials.

The facts were shocking: thousands of undertrial prisoners in Bihar jails had been detained for periods longer than the maximum punishment for their alleged offences. Many were too poor to afford bail. Some had been forgotten by the system entirely.

Justice Bhagwati held this was a gross violation of Article 21 of the Constitution of India. The right to life and liberty includes the right to speedy trial. The Supreme Court emphasized that Article 21 includes the right to a speedy trial and release. Prolonged detention without trial is arbitrary and unconstitutional.

Connection Between Bail and Article 21

Hussainara Khatoon (supra) established that bail is intrinsically linked to Article 21 of the Constitution of India. Your constitutional right to liberty means the state cannot keep you in jail indefinitely waiting for trial. Courts must consider the delay in trial when deciding bail applications.

The judgment mandated that if you cannot afford bail, courts should release you on personal recognizance (personal bond without sureties). Poverty cannot be a barrier to liberty. This principle led to massive releases of undertrial prisoners and reforms in the bail system to accommodate indigent accused.

Uday Mohanlal Acharya vs State of Maharashtra (2001): Default Bail as Indefeasible Right

Right Accrues Automatically After Time Limit

Uday Mohanlal Acharya vs. State of Maharashtra [(2001) 5 SCC 453] judgment is the leading authority on default bail. In this judgment, the Supreme Court clarified the concept of default bail. It held that the right to default bail becomes absolute if the charge sheet is not filed within the prescribed period, and the accused applies for bail and is prepared to furnish bail.

The Court established that default bail is an “indefeasible right”; meaning it cannot be defeated or taken away once it accrues. This right exists automatically by operation of law when the time period expires without a chargesheet being filed.

Subsequent Chargesheet Cannot Defeat the Right

Here’s the critical holding: The court emphasized that this right cannot be defeated by subsequent filing of the charge sheet before the actual release of the accused. Once the 60 or 90 days pass without a chargesheet, your right to default bail crystallizes. Even if police rush to file the chargesheet later that day, your right remains.

The only requirement is that you must actually apply for default bail and be prepared to furnish it. If you delay and the chargesheet is filed before you apply, you may lose the benefit. But if you’ve applied on time, the subsequent chargesheet filing cannot defeat your right to release.

This judgment has become a powerful tool for accused persons languishing in custody due to investigation delays. It forces investigating agencies to work efficiently and protects you from indefinite detention.

Sanjay Chandra vs CBI (2012): Pre-Trial Detention Limits

When Seriousness of Offence Cannot Alone Justify Bail Denial

The Sanjay Chandra judgment addressed a critical question: can bail be denied solely because the offence is serious? In Sanjay Chandra v. CBI [AIR 2012 SUPREME COURT 830], the Supreme Court underscored that bail should not be denied solely on the basis of the seriousness of the offence if there is no likelihood of the accused tampering with evidence or fleeing.

The Court held that seriousness of the offence alone is insufficient to deny bail. While it’s a relevant consideration, it cannot be the only factor. Courts must look at the entire picture: is there genuine flight risk? Will you tamper with evidence? Are witnesses likely to be threatened?

Factors Courts Must Consider

Sanjay Chandra (supra) emphasized that the primary purpose of bail is to ensure the accused’s presence at trial. The court noted that prolonged pre-trial detention undermines the presumption of innocence.

The judgment listed factors courts should consider: (1) nature and seriousness of the offence, (2) character of evidence, (3) circumstances peculiar to the accused, (4) reasonable possibility of securing presence at trial, (5) reasonable apprehension of witnesses being tampered with, (6) larger interests of the public or state.

Critically, the Court held that these factors must be weighed holistically, not mechanically. Ticking boxes isn’t enough; courts must engage substantively with your specific circumstances.

Arnesh Kumar vs State of Bihar (2014): Guidelines Against Arbitrary Arrests

Preventing Misuse of Arrest Powers in Cognizable Offences

The Arnesh Kumar judgment tackled the widespread problem of unnecessary arrests. In Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 2756), the Supreme Court laid down guidelines to prevent unnecessary arrests and detention, emphasizing that bail should be the norm in offences punishable by less than seven years of imprisonment.

Police often arrest people routinely in cognizable offences without considering necessity. This caused immense harassment, particularly in matrimonial disputes where multiple FIRs would be filed and all family members arrested indiscriminately.

Mandatory Notice Requirement Before Arrest

The Court issued mandatory guidelines: (1) Police officers must not automatically arrest when investigating offences punishable with less than 7 years imprisonment, (2) Police must issue notice to the accused to appear before them for interrogation, (3) Arrest should be made only if police have genuine reasons to believe arrest is necessary, (4) Police must record reasons in writing if they arrest someone in such cases, (5) Magistrates should not authorize detention routinely; they must verify that police have followed proper procedure.

These guidelines significantly reduced unnecessary arrests and made bail more accessible in less serious offences. If you’re accused of an offence with punishment below 7 years, you have strong grounds to argue the police should have issued notice rather than arresting you.

Arnab Goswami vs State of Maharashtra (2020): Personal Liberty is Paramount

Judiciary’s Duty to Protect Fundamental Rights

Arnab Goswami vs the State of Maharashtra and Ors. [(AIR 2021 SUPREME COURT 1)], decided during the COVID-19 pandemic, powerfully reaffirmed the judiciary’s role as protector of liberty. The Supreme Court granted interim bail to journalist Arnab Goswami, highlighting that deprivation of personal liberty for even a single day is too much.

The Court was critical of the lower courts’ approach, which seemed to prioritize the seriousness of allegations over constitutional rights. The Supreme Court emphasized that regardless of who you are or what you’re accused of, your fundamental rights cannot be ignored.

Even One Day’s Deprivation is Too Much

The court stressed that the judiciary must protect the fundamental right to personal liberty. The judgment stated that even a single day’s wrongful deprivation of liberty is too much. Courts cannot be casual about detention; each day in custody is a violation if detention is unjustified.

This judgment has emboldened bail applicants to challenge prolonged detention and demand that courts actively protect liberty rather than passively rubber-stamp prosecution objections.

Satender Kumar Antil vs CBI (2022): Bail Guidelines for Uniform Application

Streamlining Bail Procedures Across India

Satender Kumar Antil vs CBI [(2021) 10 SCC 773] judgment is the most recent and comprehensive statement on bail law. In Satender Kumar Antil (supra), the Supreme Court laid down guidelines to ensure that bail procedures are streamlined and followed uniformly across the country.

The Court noted wide variations in how different High Courts and lower courts approached bail applications. Some were liberal, others restrictive. This inconsistency violated the rule of law; your liberty shouldn’t depend on which judge you appear before.

Categories of offences for bail purposes

In this judgment, the Supreme Court established four distinct categories of offences to guide bail decisions uniformly. Category 1 includes offences punishable with imprisonment up to 7 years (excluding specific serious crimes like those under NDPS, UAPA, or economic offences), where bail should generally be granted. Category 2 covers offences punishable with more than 7 years but excluding life imprisonment or death penalty, requiring a balanced approach considering case circumstances. Category 3 encompasses grave offences punishable with life imprisonment or death, offences under special statutes like NDPS/UAPA/PMLA, and crimes against women/children, where bail requires exceptional circumstances and stricter scrutiny. Category 4 addresses cases involving violation of bail conditions, where courts must assess the nature and seriousness of the breach before canceling bail.

Preventing Arbitrary Detention

The judgment directed lower courts to adhere strictly to the principles governing bail to prevent arbitrary detention. The Court issued comprehensive guidelines covering all aspects of bail: factors to consider, how to exercise discretion, timelines for deciding applications, and the importance of reasoned orders.

The Antil guidelines emphasise that bail is the rule, detention is the exception, and courts must actively justify detention rather than passively accepting prosecution objections. Lower courts cannot mechanically deny bail; they must engage with the specific facts and apply established principles.

What Changed in BNSS Compared to CrPC: Bail Provisions

India underwent a transformative legal change in 2023 when the government replaced the colonial-era Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) 1973 with the new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023. If you’re navigating the bail process now, you need to understand what changed and what stayed the same.

Introduction to BNSS 2023 (Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita)

When Did BNSS Replace CrPC?

The Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023 was introduced to replace the Code of Criminal Procedure 1973. The BNSS came into effect on July 1, 2024, alongside two other new criminal laws: the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita 2023 (BNS) replacing the Indian Penal Code 1860, and the Bharatiya Sakshya Adhiniyam 2023 (BSA) replacing the Indian Evidence Act 1872.

This represents the most significant overhaul of India’s criminal justice system since independence. The government framed these new laws with the stated objective of removing colonial provisions and making criminal procedure more efficient, victim-centric, and aligned with modern requirements.

Why BNSS Was Enacted

The BNSS aimed to modernize procedures, reduce delays, incorporate technology, and make the system more transparent and accessible.

Key objectives included: (1) simplifying complex procedures, (2) incorporating provisions for electronic filing and virtual hearings, (3) mandating timelines for various stages to reduce delays, (4) strengthening victims’ rights, and (5) updating the law to reflect contemporary society and technology.

However, critics have noted that many provisions remain substantially similar to the CrPC, with changes being more cosmetic (different section numbers) than substantive. For bail provisions specifically, the fundamental framework remains largely unchanged. You can have a look at it below

CrPC vs BNSS: What Changed in Bail Laws (2023)

Quick Comparison Table

Here’s a quick reference showing how CrPC sections correspond to BNSS sections:

| CrPC Section | BNSS Section | Subject matter |

| 436 | 478 | Bail in bailable offence |

| 437 | 480 | Bail in non-bailable offence |

| 438 | 482 | Anticipatory bail |

| 439 | 483 | Special powers of the High Court/Sessions Court regarding bail |

| 440 | 484 | Amount of bond and reduction thereof |

| 441 | 485 | Bond of accused and sureties |

Key Changes You Should Know

- Formal Definitions Added: The BNSS 2023 has introduced formal definitions for related terms in Section 2(1)(b), which defines bail as “the release of a person from custody upon execution of a bond.” Section 2(1)(d) of BNSS defines a bail bond as “an undertaking to appear before the court or investigating officer as directed.”

This is significant because the CrPC never formally defined “bail” or “bail bond.” The BNSS provides clarity by codifying what courts had long interpreted these terms to mean.

- Zero FIR Across All Police Stations

Under Section 173 of BNSS, any police station in India must register an FIR regardless of territorial jurisdiction, eliminating the previous practice of turning away complainants. This change addresses a major complaint against the old system where victims faced bureaucratic hurdles in registering complaints.

- Technology Integration: The BNSS emphasizes electronic filing, virtual hearings, and digital documentation. Section 183 BNSS/ Section 164 CrPC now explicitly allows recording of statements via video conference. This makes the bail process potentially more accessible; you can file applications electronically and attend some hearings virtually.

- Complete Digitalization of Criminal Justice System (Sections 173 and 530 of BNSS): The BNSS mandates electronic filing of FIRs, complaints, petitions, and applications, along with the use of video conferencing for trials and proceedings. Courts are required to maintain digital records, allow virtual testimonies, and provide online case tracking facilities to all stakeholders. This comprehensive digital transformation aims to increase accessibility, reduce delays, and bring transparency to the criminal justice system.

- Clarification on Electronic Sureties: The BNSS explicitly recognizes electronic execution of bonds and digital verification of sureties, making it easier to arrange bail remotely or when physical presence is difficult.

Section Mapping: Old to New

When filing a bail application now, you must cite BNSS sections, not CrPC sections. However, I recommend citing both; for example: “Section 478 BNSS (earlier Section 436 CrPC).” This approach helps because:

- Continuity of Jurisprudence: All the case laws developed under CrPC sections remain valid and applicable. The Supreme Court judgments discussed earlier: Balchand, Sibbia, Hussainara Khatoon, Sanjay Chandra, and others; were decided interpreting CrPC provisions. These precedents continue to guide BNSS interpretation because the provisions are substantially similar.

- Judicial Familiarity: Many judges are still adjusting to the new section numbers. Citing both old and new sections helps ensure your application is understood clearly and the relevant precedents are considered.

- Legal Clarity: If there’s any ambiguity or dispute about interpretation, referencing the corresponding CrPC provision and its established judicial interpretation helps clarify your position.

Conclusion

Bail represents the delicate balance our legal system must strike between individual liberty and public safety. Throughout this guide, I’ve walked you through the comprehensive framework of bail law in India; from the constitutional protections that guarantee your right to liberty to the practical mechanics of how different types of bail work.

Remember these core principles as you navigate the bail process: You are presumed innocent until proven guilty. Bail is the rule, jail is the exception. Your fundamental right to liberty under Article 21 cannot be arbitrarily curtailed. Courts must justify detention, not grant of bail.

Whether you’re seeking regular bail after arrest, anticipatory bail to protect yourself from potential arrest, interim bail for temporary relief, or default bail as your indefeasible statutory right; the law provides pathways to secure your freedom while your case proceeds. Understanding the specific conditions for bail empowers you to comply strictly and avoid bail cancellation.

The transition from CrPC to BNSS 2023 hasn’t fundamentally altered your bail rights; the landmark Supreme Court judgments establishing bail jurisprudence remain your strongest legal foundation. Whether citing Balchand’s (supra) “bail is rule, jail is exception,” Sibbia’s (supra) liberal interpretation of anticipatory bail, or Uday Mohanlal Acharya’s (supra) protection of default bail as an indefeasible right, these precedents continue to shield your liberty.

If you’re facing criminal charges, act swiftly. Engage a competent lawyer immediately. Understand which type of bail applies to your situation. File applications promptly; especially for default bail where timing is critical. Comply strictly with all conditions imposed. Your freedom, reputation, livelihood, and family depend on navigating this process correctly.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bail in India

Can I get bail if charged with a non-bailable offence?

Yes, you can get bail even for non-bailable offences, but it’s discretionary. Courts consider factors like offence severity, evidence strength, flight risk, and witness tampering potential before granting bail in such cases.

What is the difference between bailable and non-bailable offences?

Bailable offences (typically punishable by less than 3 years) grant automatic bail as a right, while non-bailable offences (serious crimes with 3+ years punishment) require court discretion based on case circumstances.

Which court should I approach for bail?

For bailable offences, approach the police station or Magistrate Court. For non-bailable offences, file in Magistrate Court or Sessions/High Court. For anticipatory bail, approach Sessions Court or High Court only.

What is default bail and when am I entitled to it?

Default bail is your automatic right when police fail to file chargesheet within 60 days (for offences below 10 years) or 90 days (for death/life/10+ years offences) from arrest.

Can anticipatory bail be rejected?

Yes, courts can reject anticipatory bail if you have criminal antecedents, the offence is particularly heinous, there’s evidence of witness tampering, or you’re likely to abscond.

What happens if I violate bail conditions?

Violating bail conditions leads to bail cancellation, immediate re-arrest on non-bailable warrant, bond forfeiture, and difficulty obtaining fresh bail due to breach of trust.

Can bail be cancelled after it’s granted?

Yes, bail can be cancelled if you violate conditions, abscond, tamper with evidence, threaten witnesses, commit new offences, or if the original bail order was obtained through misrepresentation or fraud.

What is the difference between bail and bond?

Bail is the release from custody while trial proceeds. Bond is the legal undertaking (with or without monetary security) you provide to guarantee your court appearance; the mechanism that secures your bail.

Do I need a lawyer to apply for bail?

While not legally mandatory, hiring a criminal lawyer is strongly recommended. Bail applications require proper legal drafting, knowledge of precedents, strategic arguments, and courtroom advocacy that significantly improve chances of grant.

Can I travel outside India while on bail?

No, unless you obtain specific court permission. Bail conditions typically require passport surrender and travel restrictions. You must file an application with valid reasons (medical emergency, business) to seek temporary travel permission.

What are the standard bail conditions imposed by courts?

Standard conditions include: personal bond with/without sureties, passport surrender, regular police reporting, jurisdiction restrictions, no witness contact, no evidence tampering, mandatory court appearances, and no new offences while on bail.

How is BNSS different from CrPC regarding bail?

BNSS 2023 renumbers CrPC provisions and adds formal bail definitions, but fundamental bail rights, principles, and procedures remain substantially unchanged from CrPC framework.

Is bail possible in murder cases?

Yes, though difficult. Courts grant bail in murder cases considering evidence strength, investigation completion, accused’s background, etc.. The High Court/Supreme Court may grant it if the prosecution case is weak.

What if bail is rejected by the lower court?

File a fresh bail application in Sessions Court or High Court citing changed circumstances or additional grounds. Courts at different levels exercise independent jurisdiction; rejection by Magistrate doesn’t bar Sessions/High Court bail applications.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications