Complete guide to bail meaning in India: Definition, constitutional rights, types of bail, legal framework, and what bail means for your liberty and case.

Table of Contents

What is Bail?

At its most fundamental level, bail is the temporary release of a person accused of a crime from police custody or judicial detention. When you’re granted bail, you’re allowed to remain free while your criminal case proceeds through investigation, trial, and judgment. However, this freedom comes with specific conditions; primarily, you must appear in court whenever required and comply with all conditions imposed by the court. Think of bail as a legal promise: “I will attend all court hearings and follow the court’s orders while my case is being decided.”

Bail represents a delicate balance in our criminal justice system. On one side stands your constitutional right to personal liberty under Article 21 and the fundamental legal principle that you’re innocent until proven guilty. On the other side lies the judiciary’s and society’s legitimate interest in ensuring you appear for trial, don’t interfere with witnesses or evidence, and don’t commit further offences while on bail. Bail is the mechanism that reconciles these competing interests, embodying the golden principle established by the Supreme Court in cases such as State of Rajasthan v. Balchand (1977 AIR 2447) and Satender Kumar Antil v. Central Bureau of Investigation [(2021) 10 SCC 773]: “Bail is the rule, jail is the exception.”

When you or someone you know faces arrest, understanding bail becomes critically important. Whether you’re an accused person, a concerned family member, a law student, or simply someone trying to understand India’s criminal justice system, knowing what bail truly means empowers you to assert your rights and make informed decisions. This comprehensive guide will explain everything you need to know about bail meaning in India; from basic definitions and constitutional protections to landmark Supreme Court judgments and practical implications for your daily life while criminal proceedings continue.

Bail: Definition and Meaning

The term “bail” comes from the old French word “bailer” which means “to give” or “to deliver.” This etymology captures the essence of bail; you’re delivered from custody temporarily, given back your freedom, but you also give your word (backed by security) that you’ll return to face justice. This ancient concept has evolved over centuries from Socrates’ time in 399 BC through medieval British courts to modern Indian constitutional democracy.

Black’s Law Dictionary Definition of Bail: According to Black’s Law Dictionary, one of the most authoritative legal dictionaries worldwide, bail is defined as “the security required by a court for the release of a prisoner who must appear at a future time” or “procuring the release of a person from legal custody, by undertaking that he/she shall appear at the time and place designated and submit him/herself to the jurisdiction and judgment of the court.”

The Supreme Court of India has also defined bail with remarkable clarity. In the landmark case of Kamlapati v. State of West Bengal (1979 AIR 777), the Court explained that bail is “a mechanism established for attaining the synthesis of two essential conceptions of human worth; namely, the right of an accused to personal freedom and the public interest in which a person’s release is conditional on the surety producing the accused person in court to stand trial.“

It’s crucial to understand what bail is NOT. Bail does not mean your case is dismissed or that you’re free from criminal charges. It doesn’t mean you’ve been found innocent, nor does it mean you’re guilty. Bail simply means you don’t have to remain in custody while the legal process unfolds. You’re still required to face trial, still obligated to cooperate with the investigation, and still bound by the criminal justice system: just not from behind bars.

Bail Meaning: Constitutional and Legal Framework

Bail Meaning: Essence in the Constitution

Article 21 of the Constitution of India: Right to Life and Personal Liberty

The constitutional foundation of bail in India rests on Article 21 of the Constitution, which guarantees every person the right to life and personal liberty. This isn’t merely about biological existence; it encompasses the right to live with human dignity, freedom of movement, and the ability to pursue one’s profession and relationships. When you’re arrested and detained, Article 21 is directly implicated.

Article 21 states: “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.” This means that while the state can deprive you of liberty through arrest and detention, it must follow fair, just, and reasonable procedures. Bail emerges as a critical mechanism to protect this fundamental right; ensuring you’re not kept in custody unnecessarily while awaiting trial.

The Supreme Court in Kalyan Chandra Sarkar and Ors. vs. Rajesh Ranjan and Ors. (AIR 2005 SUPREME COURT 921) has interpreted Article 21 liberally when it comes to bail. The Court has held that prolonged detention without trial violates the very essence of Article 21. Every day you spend in custody before being convicted is a day of liberty lost that can never be restored, even if you’re ultimately acquitted. This understanding forms the philosophical foundation for why bail should be granted liberally rather than restrictively.

Presumption of Innocence Until Proven Guilty

One of the bedrock principles of criminal justice is that you’re presumed innocent until the prosecution proves your guilt beyond reasonable doubt. This presumption isn’t just a procedural nicety; it’s a fundamental protection that shapes how bail decisions should be made. If you’re presumed innocent, how can prolonged pre-trial detention be justified?

This principle means that at the bail stage, the court isn’t determining whether you committed the alleged offence. That determination comes much later at trial after full evidence is presented and examined. At the bail stage, the question is much narrower: Should you be kept in custody while awaiting trial, or should you be released with conditions that ensure you’ll face justice?

The presumption of innocence principle argues strongly for granting bail in most cases. If you’re presumed innocent, the default position should be liberty, not incarceration. Custody before conviction should be the exception, not the rule – reserved only for situations where there’s genuine reason to believe you’ll abscond, tamper with evidence, or threaten witnesses.

“Bail is the Rule, Jail is the Exception” – What This Principle Means

This famous principle, established by the Supreme Court in State of Rajasthan (supra), has become the guiding philosophy for bail in India. But what does it actually mean for you if you’re seeking bail? It means that courts should start from the presumption that bail should be granted, and only refuse it if there are compelling reasons specific to your case.

“Bail is the rule, jail is the exception” reflects the constitutional values we’ve just discussed: Article 21‘s protection of liberty and the presumption of innocence. It means that being kept in custody before trial should not be the normal course. Instead, you should generally be released on bail unless the prosecution demonstrates specific grounds why custody is necessary.

However, this principle operates differently depending on the nature of the offence you’re accused of. For bailable offences, bail truly is your absolute right. For non-bailable offences, courts have more discretion but must still apply this principle; considering liberty as the norm and custody as the exception that requires justification. The principle doesn’t mean bail is automatic in every case, but it does mean courts must approach bail applications with a presumption in favor of personal liberty.

Indian Legal Framework on Bail

Relevant Provisions under Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC)

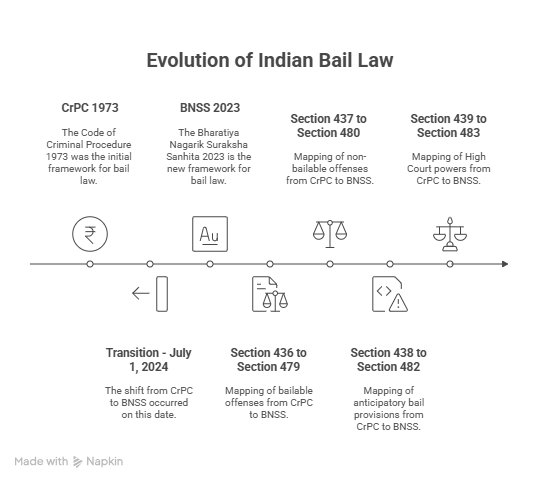

Until July 1, 2024, the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 (CrPC) governed all aspects of bail in India. Even though it’s now been replaced by the BNSS, understanding CrPC provisions remains important because decades of case law and legal interpretation were built on this framework. Many lawyers and judges still reference CrPC sections when discussing bail principles.

Section 436 CrPC dealt with bail in bailable offences, establishing that if you’re accused of a bailable offence, you have an absolute right to be released on bail. The police officer or court cannot refuse you bail if you’re ready to furnish the required bond. This makes bail truly a right, not a favor, for less serious offences.

Section 437 CrPC addressed bail in non-bailable offences. This section gave Magistrates the power to grant bail even in serious offences, but with important limitations. If there are reasonable grounds to believe you’ve committed an offence punishable with death or life imprisonment, bail can be refused. The section also provided special consideration for women, children, and sick or infirm persons.

Section 438 CrPC introduced the concept of anticipatory bail; allowing you to seek bail before arrest if you have reason to believe you might be arrested for a non-bailable offence. This section was based on the 41st Law Commission Report’s recommendation to protect people from being falsely implicated and arrested in fabricated cases.

Section 439 CrPC gave the High Court and Sessions Court broader powers to grant bail, even in cases where Magistrates might refuse. These higher courts could consider factors beyond what Magistrates could, providing an important safeguard against unjust detention. Sections 440-450 dealt with bail bonds, sureties, and conditions.

Relevant Provisions under Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023

On July 1, 2024, the Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023 replaced the CrPC, bringing India’s criminal procedure laws into a new era. While the fundamental principles of bail remain largely unchanged, the BNSS introduces some modifications and provides clearer definitions in certain areas. Understanding these new provisions is essential for anyone dealing with bail today.

Section 479 BNSS (replaced by Section 436A of CrPC) addresses the critical issue of undertrial prisoners who’ve been in custody for extended periods. If you’ve been detained for half the maximum sentence prescribed for the offence you’re accused of, you’re entitled to be released on bail. This provision prevents indefinite pre-trial detention that violates your fundamental rights.

Section 480 BNSS (replacing Section 437 CrPC) governs bail in non-bailable offences with similar provisions as before, but with updated language. The section retains special consideration for women, children, and sick persons. It also maintains the power of courts to impose conditions when granting bail to ensure you appear for trial and don’t interfere with the investigation.

Section 482 BNSS (replacing Section 438 CrPC) continues the provision for anticipatory bail. The fundamental right to seek pre-arrest bail remains intact, though courts continue to exercise this power carefully, balancing your liberty against preventing potential abuse where false allegations might lead to arrest.

Section 483 BNSS (replacing Section 439 CrPC) preserves the High Court’s and Sessions Court’s broader powers to grant bail. These courts can consider the entire range of circumstances in your case, examining not just the offence alleged but also factors like your personal background, likelihood of trial attendance, and potential for evidence tampering. Sections 484-492 BNSS deal with bail bonds, sureties, and related procedures.

Supreme Court Guidelines

Beyond statutory provisions, the Supreme Court has issued numerous guidelines that shape how bail works in practice. These guidelines emerge from specific cases but establish principles that all courts across India must follow. Understanding these guidelines helps you know what factors courts will consider when deciding your bail application.

Hussainara Khatoon vs State of Bihar (1979)

The Supreme Court in Hussainara Khatoon v. Home Secretary, State of Bihar (1979 AIR 1369), held that prolonged detention without trial violates the right to speedy trial under Article 21. The Court directed that undertrial prisoners who have already spent time in custody equal to or exceeding the maximum punishment for their alleged offence must be released immediately, even without formal bail applications.

Sanjay Chandra vs Central Bureau of Investigation (2012)

The Supreme Court in Sanjay Chandra v. CBI [AIR 2012 SUPREME COURT 830 held that economic offences cannot be treated as a separate category where bail is automatically refused regardless of magnitude. The judgment clarified that bail considerations remain uniform across all offence types; likelihood of fleeing, tampering with evidence, and influencing witnesses and that public pressure or media outcry cannot justify denying bail.

Arnesh Kumar vs State of Bihar (2014)

The Supreme Court in Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 2756) directed that police must not automatically arrest accused persons in cases with punishment below seven years without recording specific reasons justifying the necessity of arrest. The Court mandated that magistrates must satisfy themselves about these reasons before authorising detention, fundamentally establishing that “arrest should be the last option” in the criminal justice system.

Satender Kumar Antil vs Central Bureau of Investigation (2022)

The Supreme Court in Satender Kumar Antil (supra) directed that bail cannot be refused merely on grounds of offence seriousness or punishment severity, and emphasized that courts must not conduct mini-trials at the bail stage. The judgment mandated that bail conditions should be reasonable and not so stringent that they defeat the purpose of granting bail, while stressing particular sensitivity toward undertrials who have spent substantial time in custody.

Bailable and Non-bailable Offences Explained

What is a Bailable Offence? Definition and Meaning

A bailable offence is one where bail is your absolute right; not something the court has discretion to grant or refuse. If you’re arrested for a bailable offence, either the police officer who arrested you or the court before which you’re produced must release you on bail once you’re ready to furnish a bail bond. This makes bailable offences fundamentally different from non-bailable ones in terms of how bail works.

Under Section 2(c) BNSS 2023/Section 2(a) CrPC, a bailable offence is defined as an offence shown as bailable in the First Schedule of the CrPC/BNSS or made bailable by any other law currently in force. Generally, bailable offences are less serious crimes, typically punishable with imprisonment of three years or less, or with just a fine. These include offences like simple hurt, defamation, public nuisance, and certain property-related crimes.

The philosophy behind bailable offences reflects the “bail is the rule” principle we discussed earlier. For less serious crimes, society’s interest in keeping you in custody is minimal, while your right to liberty remains paramount. Since you’re presumed innocent and the offence isn’t extremely grave, there’s no justification for keeping you detained while awaiting trial. You can immediately secure your release by providing the required bail bond.

What is a Non-Bailable Offence? Definition and Meaning

A non-bailable offence is one where bail is not automatically granted as a matter of right. Instead, the court has discretion to grant or refuse bail after considering various factors. This doesn’t mean bail cannot be granted;it simply means the decision requires judicial consideration of your specific circumstances and the nature of the offence alleged against you.

Section 2(c) BNSS/Section 2(a) CrPC defines non-bailable offences as “any other offence” not classified as bailable. Generally, these are serious crimes punishable with imprisonment of three years or more, including offences like murder, rape, kidnapping, robbery, serious fraud, and crimes under special statutes like the NDPS Act or Prevention of Corruption Act. The gravity of these offences justifies additional scrutiny before releasing you on bail.

When you apply for bail in a non-bailable offence, courts under Section 437 CrPC/ Section 480 BNSS consider several factors. The court examines whether there are reasonable grounds to believe you committed the offence, your likelihood of fleeing from justice, potential for tampering with evidence or threatening witnesses, your criminal history, and the strength of the prosecution’s case. However, even for serious offences, courts must balance society’s interest against your fundamental right to liberty, keeping in mind that you’re still presumed innocent until proven guilty.

Types of Bail in India

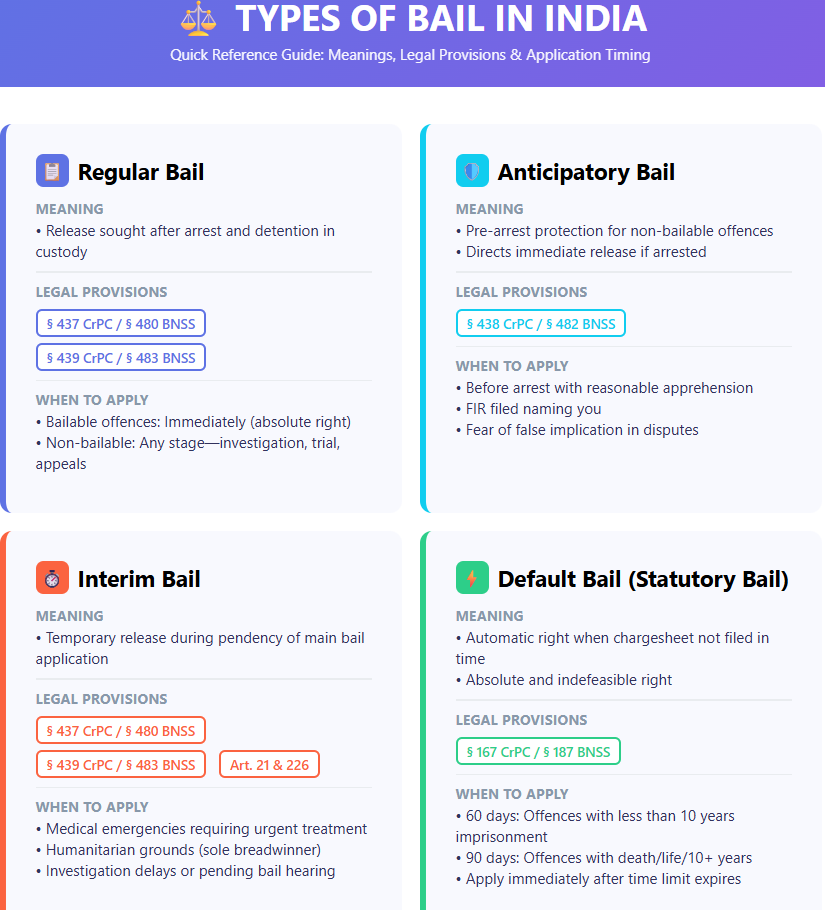

Regular Bail – Meaning and When to Apply

Regular bail is what most people think of when they hear the word “bail.” It’s the release granted by a court after you’ve already been arrested and are in police custody or judicial custody. If you find yourself detained; whether in a police station after arrest or in jail after being remanded by a Magistrate; you would apply for regular bail to secure your release while your case proceeds.

You can apply for regular bail under Section 437 or 439 of CrPC (now Sections 480 and 483 BNSS). If your case is before a Magistrate, you’d typically file your bail application before that Magistrate under Section 437/480. If bail is refused at the Magistrate level or if your case involves serious offences, you can approach the Sessions Court or High Court under Section 439/483, which have broader powers to grant bail.

The timing for applying for regular bail is important. You can file a bail application at any stage after arrest; immediately after being taken into police custody, after being produced before the Magistrate and remanded, or even later during the investigation or trial. However, it’s generally advisable to apply as soon as possible after arrest, since every day in custody is a day of liberty lost. Your lawyer will assess the strength of the prosecution’s case, gather supporting documents, and file the bail application before the appropriate court with the best chance of success.

Anticipatory Bail – Meaning and When to Apply

Anticipatory bail, also called pre-arrest bail, is a unique provision that allows you to seek bail before you’re actually arrested. If you have reason to believe that you might be arrested for a non-bailable offence; perhaps you’ve learned that an FIR has been filed against you or that the police are looking for you; you can approach the Sessions Court or High Court seeking anticipatory bail under Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS.

The concept of anticipatory bail was introduced based on the recommendation of the 41st Law Commission of India Report. The Commission recognised that influential people sometimes misuse the criminal justice system to falsely implicate their rivals, getting them arrested to harass them or damage their reputation. Anticipatory bail provides protection against such malicious prosecution by ensuring you’re not arrested and humiliated if the allegations against you are fabricated or without merit.

When should you apply for anticipatory bail? The moment you genuinely apprehend arrest in a non-bailable offence, you should consult a lawyer and consider filing an anticipatory bail application. Don’t wait until the police arrive at your door; by then it may be too late. The application must demonstrate specific facts showing why you believe arrest is likely and why pre-arrest bail is justified. Courts grant anticipatory bail when satisfied that you’re cooperating with investigation, unlikely to flee, and the allegations appear questionable or require further scrutiny.

Interim Bail – Meaning and When to Apply

Interim bail is a temporary form of bail granted for a short period, typically while your application for regular bail or anticipatory bail is pending before the court. Think of it as emergency relief; a court might grant you interim bail if your regular bail application can’t be heard immediately but keeping you in custody would cause irreparable harm, particularly to your reputation or if you have urgent medical or personal circumstances.

Though the CrPC didn’t explicitly define interim bail, courts have recognized the power to grant it as inherent in their authority to grant bail. The Supreme Court in cases like Sukhwant Singh & Ors v. State of Punjab (2010 AIR SCW 1185) held that interim bail serves to protect the accused’s reputation and right to liberty under Article 21, preventing the stigma and damage that can result from even brief periods of detention.

When is interim bail appropriate? If you’ve filed a bail application but the court can’t hear it immediately due to court schedules or the need for the judge to examine case records, interim bail can protect you during this waiting period. Similarly, if you’re seeking anticipatory bail and the matter will take time to decide, the court might grant interim protection to prevent your arrest while the application is considered. Interim bail is typically granted with conditions and for a specific period; it’s not a substitute for regular or anticipatory bail but rather a temporary bridge until your main bail application is decided.

Default Bail: Meaning

Default bail, also called statutory bail, is perhaps the most automatic form of bail in Indian law. It arises not from the court’s discretion but from the investigating agency’s failure to complete the investigation within the prescribed time limits. Under Section 167 CrPC/Section 187 BNSS, if you’re arrested and the police don’t file a chargesheet within the legally mandated period, you become entitled to bail as an indefeasible right.

The time limits are strict: 60 days for offences punishable with less than 10 years imprisonment, and 90 days for offences punishable with death, life imprisonment, or 10 years or more. These periods are calculated from the date of your arrest or remand, not from when investigation began. If the chargesheet isn’t filed within these timelines and you apply for bail, the court must grant it – there’s no discretion involved.

The Supreme Court in Uday Mohanlal Acharya vs. State of Maharashtra [(2001) 5 SCC 453] clarified that the right to default bail is absolute and indefeasible. Once the statutory period expires without chargesheet filing, you acquire this right immediately. Even if the police files the chargesheet just before you’re physically released, your right to default bail isn’t defeated. This provision serves as a crucial check against indefinite detention during investigation, ensuring agencies work within reasonable timeframes and respect your constitutional right to speedy justice.

Key Terms You Must Know About Bail

What is a Bail Bond? Definition and Meaning

A bail bond is the formal undertaking or guarantee you provide to the court when being released on bail. It’s essentially a written promise that you’ll appear before the court whenever required and comply with all conditions imposed on you. The bail bond is the mechanism that gives meaning to your release; without it, bail wouldn’t have any legal enforceability.

Under Section 441 CrPC/Section 485 BNSS, when the court grants you bail, you must execute a bond; a legal document binding you to fulfill specific obligations. This bond can be with or without sureties, depending on what the court orders. The bond specifies the amount you’re liable for if you breach bail conditions, typically by failing to appear in court when required.

There are two main types of bonds: a personal bond, where you alone are responsible for the specified amount; and a surety bond, where one or more other persons also guarantee your appearance by pledging their property or providing financial security. The amount of the bond must be reasonable – Section 440 CrPC/Section 484 BNSS specifically states that the bond amount should not be excessive. If you’re unable to afford the amount set, you can request the court to reduce it to a reasonable sum within your means.

Who is a Surety in Bail?

A surety is a person who guarantees your appearance in court and agrees to be financially responsible if you violate bail conditions. When a court grants you bail “with sureties,” it means one or more persons must stand guarantee for you by executing a surety bond promising to ensure you comply with all bail conditions, particularly appearing in court when required.

The surety essentially becomes a co-obligor with you. This makes being a surety a significant responsibility, which is why courts carefully verify the surety’s financial capacity and reliability before accepting them.

Who can be your surety? Generally, any adult Indian citizen with stable income or property can stand surety for you. The court evaluates whether the proposed surety has sufficient means to pay the bond amount if it’s forfeited. The surety must have a permanent address, be of good character, and not themselves be accused in serious criminal cases. Courts often accept family members, employers, or respected community members as sureties. The surety can apply to be discharged from their obligation under certain circumstances, but while they remain surety, they’re legally bound to ensure your compliance with bail conditions.

What is the Difference Between Bail and Parole?

Bail and parole are often confused because both involve being outside prison, but they’re fundamentally different concepts that apply at different stages of the criminal justice process.

Bail is granted before you’re convicted; it’s a form of pre-trial release while your case is under investigation or trial. When you’re on bail, you’re still presumed innocent, and the purpose is to protect your liberty while ensuring you appear for trial. Bail can be granted by police officers, Magistrates, or higher courts, and is governed by Sections 436-450 CrPC/Sections 478-492 BNSS. You’re released on bail pending the outcome of your case.

Parole, on the other hand, is granted after you’ve been convicted and are serving a prison sentence. It’s a form of supervised release for a temporary period during your sentence, typically for reasons like family emergencies, medical treatment, or good behavior. Parole is granted by prison authorities or State Government, not by courts, and is governed by prison manuals and parole rules, not by CrPC/BNSS. While on parole, you’re still serving your sentence; just outside prison walls under specific conditions. If you violate parole conditions, you’re immediately returned to prison to complete your sentence.

What is the difference between Bail, Acquittal and Probation

These three terms represent different outcomes in the criminal justice process, and confusing them can lead to serious misunderstandings about your legal status.

Bail is temporary release from custody while your case is pending. As we’ve discussed throughout this article, bail doesn’t mean your case is over or that you’ve been found innocent. It simply means you don’t have to remain in jail while awaiting trial and judgment. You’re still facing criminal charges, still required to appear in court, and the case against you continues. Bail is a procedural right during the criminal process, not an outcome.

Acquittal means you’ve been found not guilty after trial. When a court acquits you, it’s determining that the prosecution failed to prove your guilt beyond reasonable doubt. Acquittal is a final outcome; your case is dismissed, charges are dropped, and you’re completely free from that criminal proceeding. Unlike bail, which is temporary and conditional, acquittal is permanent and unconditional. You’re legally declared innocent of the charges.

Probation is an alternative to imprisonment after conviction. If you’ve been convicted of an offence but the court believes imprisonment isn’t appropriate; perhaps because you’re a first-time offender, the crime wasn’t serious, or you show genuine remorse; the court may release you on probation instead of sending you to prison. Under the Probation of Offenders Act, 1958, you’re released into the community under supervision, with conditions you must follow. Probation is a form of sentence, not release from charges. Unlike bail (pre-conviction) or acquittal (no conviction), probation follows a conviction but allows you to serve your sentence outside prison under supervision.

What Happens After Getting Bail?

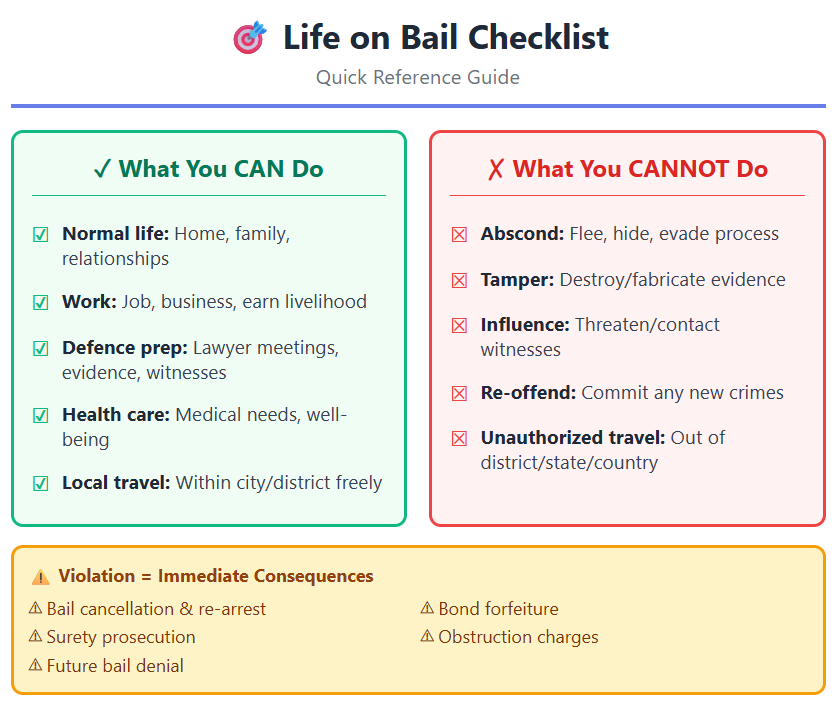

What Can You Do While on Bail?

Getting bail doesn’t mean unrestricted freedom; it means conditional liberty while your case proceeds. Understanding what you can do while on bail helps you maintain your freedom and avoid violations that could lead to bail cancellation. Let me explain the scope of activities generally permitted when you’re out on bail.

First and most importantly, you can continue with your normal daily life; living at home with your family, maintaining your personal relationships, and engaging in routine activities. This is fundamentally what bail is about: allowing you to live with dignity rather than being caged in a prison cell while presumed innocent. You can take care of your health, attend to personal matters, and maintain your physical and mental well-being.

You can continue working or running your business while on bail. Article 21‘s protection of life and personal liberty includes your right to livelihood. Unless the court specifically restricts your employment (perhaps because of the nature of the offence or risk of evidence tampering related to your work), you’re free to earn a living, support your family, and maintain your professional responsibilities. You can attend your office, meet clients, and conduct business as usual.

You’re also free to prepare your defence; this is actually one of the crucial reasons bail exists. While on bail, you can freely meet with your lawyer, discuss strategy, gather evidence supporting your defense, identify and contact potential witnesses, and prepare documents needed for trial. Being outside prison gives you a far better opportunity to participate actively in your own defense than if you were in custody with limited access to your lawyer.

What Are You Not Allowed to Do on Bail?

While bail gives you significant freedom, it comes with important restrictions you must strictly follow. Violating these restrictions can lead to immediate bail cancellation, re-arrest, and return to custody. Understanding these prohibitions is critical for protecting your freedom while on bail.

The most fundamental prohibition is against absconding or attempting to evade the legal process. You cannot flee the jurisdiction, go into hiding, or attempt to avoid arrest if your bail is cancelled. Doing so would defeat the entire purpose of bail; ensuring your appearance in court for trial. If you abscond while on bail, the court will issue a non-bailable warrant for your arrest, forfeit your bail bond, and potentially prosecute your sureties who guaranteed your appearance.

You’re absolutely prohibited from tampering with evidence, threatening or influencing witnesses, or otherwise interfering with the investigation or trial. This is one of the primary concerns courts have when granting bail; ensuring you don’t misuse your freedom to obstruct justice. Any attempt to contact prosecution witnesses with threats or inducements, destroy or fabricate evidence, or pressure anyone connected with the case to change their testimony will result in immediate bail cancellation and potential additional charges for obstructing justice.

You cannot commit any similar offence while on bail. If you’re arrested for a new offence, particularly one similar to what you’re already facing charges for, courts will view this extremely seriously. Such conduct demonstrates that you haven’t learned from your alleged previous mistakes and that releasing you poses continued risk to society. Many bail orders specifically include a condition that you won’t commit any offence while on bail; violating this can lead to cancellation of your bail and denial of future bail applications.

Travel restrictions are among the most common bail conditions, particularly in serious offenses. While you’re generally free to move within your city or district for daily activities like work, family visits, and court appearances, traveling outside your home district or state typically requires prior court permission. International travel is almost always restricted, with courts commonly requiring you to surrender your passport to prevent you from leaving the country and evading trial. If you need to travel outside the permitted area for emergencies, medical treatment, or essential business, you must file an application seeking the court’s permission; traveling without authorization can result in immediate bail cancellation, even if your reasons were legitimate.

Landmark Supreme Court Cases on Bail

Gudikanti Narasimhulu vs. Public Prosecutor, High Court of Andhra Pradesh, AIR 1978 SC 429

Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer in this celebrated judgment articulated that bail jurisprudence is integral to constitutional values and must be developed with sensitivity to liberty, justice, and public welfare. The Court famously observed that “the issue of bail is one of liberty, justice, public safety and burden of the public treasury, all of which insist that a developed jurisprudence of bail is integral to a socially sensitised judicial process.”

The judgment established that courts cannot adopt a mechanical approach to bail decisions and must balance multiple constitutional and social considerations. Significantly, the Court held that economic offenses do not form a separate category where bail is automatically denied, and the severity of punishment alone cannot be the sole criterion for refusing bail.

The Court emphasized that each case must be decided on its own facts and circumstances, taking into account not just the nature of the offense but also the accused’s background, likelihood of fleeing justice, potential for evidence tampering, and the broader impact on society and the criminal justice system. The judgment established that bail is not merely a procedural matter but one deeply connected to fundamental rights, social justice, and the humane administration of criminal law, requiring judges to act as guardians of liberty while maintaining public safety.

Nikesh Tarachand Shah vs. Union of India (2018) 11 SCC 1

The Supreme Court in this landmark judgment reaffirmed the foundational principle that bail is the rule and jail is the exception, emphasizing the constitutional mandate of personal liberty under Article 21. The Court held that bail should be granted unless there are compelling reasons to refuse it, stressing that the principle “punishment begins after conviction” must be scrupulously respected.

The judgment underscored that every person is deemed innocent until proven guilty, and therefore pre-trial detention should not be used as a form of punishment. Courts must approach bail applications with the presumption favoring liberty rather than incarceration, balancing individual liberty with societal interest in ensuring trial attendance.

This judgment reinforced that deprivation of liberty even for a single day is constitutionally significant and courts cannot take such decisions lightly or mechanically. The constitutional protection of Article 21 requires courts to be liberal in granting bail and to carefully scrutinize whether custody is genuinely necessary for the investigation or trial. The case established that personal liberty is not merely a procedural consideration but a fundamental right that deserves the highest protection, and any restriction on it must be justified by clear and compelling reasons rather than routine or mechanical application of legal provisions.

Dataram Singh vs. State of Uttar Pradesh (2018) 3 SCC 22

The Supreme Court in this significant judgment held that when the investigating agency fails to file a chargesheet within the statutory period prescribed under Section 167(2) CrPC, the accused must be released on default bail as a matter of indefeasible right. The Court clarified that this right is not dependent on the accused filing a formal bail application; courts must release the accused suo motu if necessary, and the prosecution cannot defeat this right by subsequently filing a chargesheet after the expiry of the statutory period. The judgment firmly established that default bail flows from Article 21 as part of the right to life and personal liberty, and that prolonged detention without trial violates the fundamental right to speedy trial guaranteed by the Constitution.

The Court reinforced that procedural safeguards in the CrPC are not merely directory suggestions but mandatory protections of constitutional rights that courts must vigilantly enforce. The judgment directed courts to proactively monitor cases to ensure accused persons automatically receive default bail benefits upon expiry of the prescribed period, emphasizing that the burden is on the state to complete investigations efficiently rather than on citizens to languish in jail indefinitely. This decision strengthened the protection against arbitrary detention and reaffirmed that liberty cannot be sacrificed at the altar of administrative convenience or investigative delays.

Conclusion

Bail is far more than a technical legal procedure: it’s a fundamental expression of human dignity and constitutional liberty in India’s criminal justice system. When you understand what bail truly means, you recognize it as the mechanism that reconciles society’s need for justice with an individual’s right to freedom while presumed innocent.

From its ancient origins in Socrates’ Athens to Kautilya’s Arthashastra to modern constitutional democracy, bail has evolved as a humane alternative to automatic pre-trial detention. The principle “bail is the rule, jail is the exception” isn’t mere rhetoric; it reflects Article 21‘s deep commitment to personal liberty, the presumption of innocence until proven guilty, and the recognition that punishment before conviction violates fundamental human rights. Whether you’re facing bailable or non-bailable charges, seeking regular or anticipatory bail, the constitutional framework and Supreme Court guidelines are designed to protect your liberty unless compelling grounds justify custody.

If you or someone you care about faces arrest or is seeking bail, remember that bail is your right backed by constitutional protections and decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence. While the process requires navigating legal procedures, executing bail bonds, and complying with court-imposed conditions, bail ultimately means you can prepare your defense, maintain your livelihood, care for your family, and live with dignity while the legal process unfolds. Understanding bail empowers you to assert your rights, cooperate effectively with your lawyer, and approach the criminal justice system as an informed participant rather than a confused victim of circumstances beyond your comprehension.

Frequently Asked Questions About Bail Meaning in India

What is the meaning of bail in India?

Bail is the temporary release of a person arrested for a crime from police or judicial custody. When you get bail, you’re allowed to remain free while your criminal case proceeds through investigation and trial, provided you appear in court when required and comply with conditions imposed by the court.

What does bail literally mean?

The word “bail” comes from the old French word “bailer” which literally means “to give” or “to deliver.” This captures the essence of bail; the court delivers you from custody, giving you back your freedom temporarily, while you give your word (backed by security or surety) that you’ll appear for trial.

Does bail mean you are guilty or innocent?

Bail means neither guilt nor innocence. It’s a procedural right during the criminal justice process while you’re still presumed innocent. Getting bail simply means you don’t have to remain in custody while awaiting trial; it doesn’t determine whether you committed the offence. That determination comes later at trial after evidence is presented.

What is the difference between bail and jail?

Bail is released from custody while your case proceeds, whereas jail is the physical detention facility where you’re held. When you get bail, you leave jail and return to your normal life with some restrictions. Jail is the place of confinement; bail is the legal mechanism that gets you out of jail temporarily.

Is getting bail the same as being released from charges?

No, absolutely not. Getting bail means temporary release from custody while your criminal case continues. The charges against you remain active, trial will proceed, and you must appear in court when required. Release from charges happens only when the case is dismissed, withdrawn, or you’re acquitted after trial.

What does it mean when someone is granted bail?

When someone is granted bail, it means the court has ordered their release from custody subject to conditions. They must provide a bail bond (with or without sureties), promise to appear for all court hearings, and comply with restrictions like not leaving the jurisdiction or tampering with evidence. They remain free until trial concludes.

Can bail be denied even if you’re innocent?

Yes, bail can be denied even if you’re actually innocent because at the bail stage, courts don’t determine guilt or innocence. Courts may refuse bail in non-bailable offences if they believe you might flee, tamper with evidence, or threaten witnesses, regardless of whether you actually committed the offence. However, you can challenge bail denial in higher courts.

What is the meaning of bailable and non-bailable offences?

Bailable offences are less serious crimes where bail is your absolute right; police or courts must grant bail if you furnish a bond. Non-bailable offences are serious crimes where bail is not automatic; courts have discretion to grant or refuse bail after considering factors like offence severity, evidence strength, and your likelihood of attending trial.

What does surety mean in bail terms?

A surety is a person who guarantees your appearance in court by pledging their property or financial security. When courts grant bail “with sureties,” one or more persons must execute a surety bond promising to ensure you comply with bail conditions. If you violate conditions, the surety faces financial loss or prosecution.

Is bail only for rich people? What about poor accused persons?

Bail is not meant only for rich people, though the requirement of sureties and bail bonds can create economic barriers. Section 479 BNSS/Section 436A of CrPC specifically addresses this by requiring release of poor accused who’ve been in custody for half the maximum sentence. Courts must set reasonable bail amounts and can release accused on personal bonds without sureties if they’re unable to afford bail.

What is the constitutional meaning of bail?

Constitutionally, bail flows from Article 21‘s guarantee of right to life and personal liberty. It reflects the principle that you’re presumed innocent until proven guilty and shouldn’t be punished through pre-trial detention. Bail is the mechanism that balances your fundamental right to liberty against society’s interest in ensuring you face trial.

How is Indian bail different from American bail?

Indian bail focuses on ensuring court appearance through personal bonds and sureties, without necessarily requiring large cash payments. American bail often involves commercial bail bondsmen who charge fees (typically 10% of bail amount) for posting bail. India doesn’t have a commercial bail bonds industry; bail is primarily a court-supervised process involving personal and surety bonds.

What does “bail is the rule, jail is the exception” mean?

This principle established by the Supreme Court in State of Rajasthan (supra) means that when you seek bail, courts should start with a presumption in favor of granting it. Custody before conviction should be exceptional, not normal. The burden is on the prosecution to show why you should be detained, not on you to prove why you should be free.

What is the meaning of bail bond?

A bail bond is the formal written undertaking you provide to the court when released on bail, promising to appear for all hearings and comply with conditions. It specifies the amount you’re liable for if you breach conditions. The bond can be personal (you alone are liable) or with sureties (others also guarantee your appearance).

Allow notifications

Allow notifications