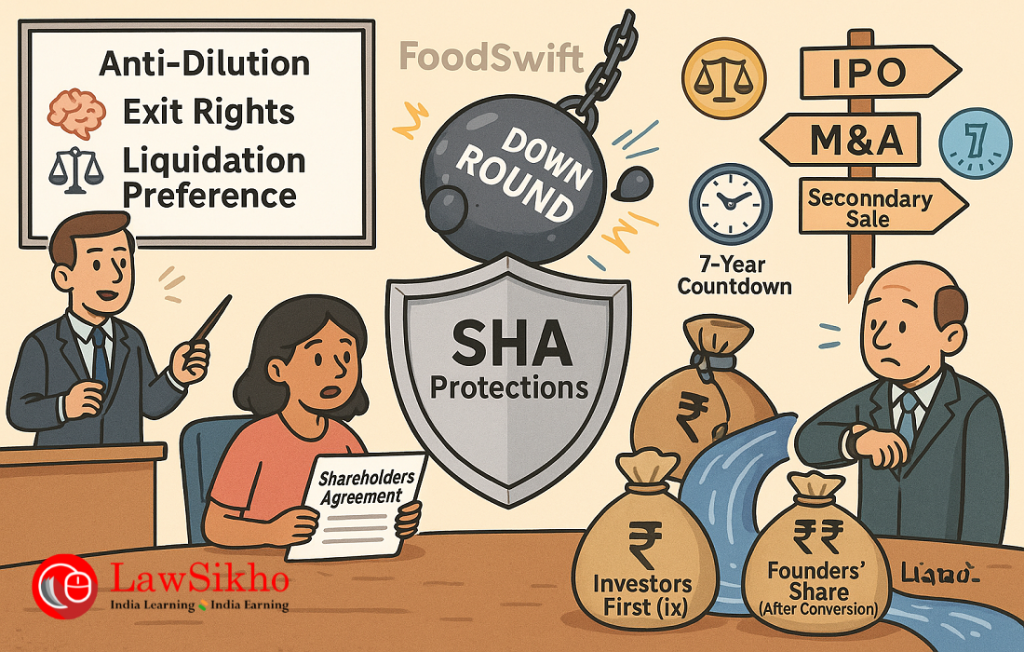

The third part of our SHA series addresses the financial payoff provisions that determine how value is distributed. Explore anti-dilution protections, liquidation preferences, and exit rights that fairly balance risk and reward in seed transactions.

Table of Contents

Introduction

“Congratulations, you have got the money. Now let us make sure you do not lose it.” Rahul and Priya exchanged puzzled glances across the conference room table.

I had just finished drafting the control provisions and transfer restrictions for FoodSwift’s shareholders’ agreement (SHA), and the founders clearly thought we were almost done.

“But we have already covered who controls what decisions and how shares can be transferred,” Priya pointed out. “What else is there?“

I smiled because this is a common reaction from first-time founders.

They tend to focus only on immediate concerns such as

- board seats,

- voting rights, and

- operational control without thinking about future funding rounds or eventual exits.

I explained to them by saying, “The control provisions we drafted protect how the company operates today. But what happens when you raise your Series A round next year? Or when a bigger player offers to acquire you three years from now?“

Rahul leaned forward, suddenly interested. “You mean we could lose control during future funding rounds?“

“Exactly,” I nodded. “Without proper protection, your 13.04% investor could end up with a much larger percentage in a down round, or you could be forced to sell the company under unfavorable terms when an exit opportunity arises.“

This is where the value protection mechanisms in a SHA become critical.

These provisions, namely, anti-dilution protections, exit rights, and liquidation preferences, may seem technical and distant when you are just getting started, but they can ultimately determine who gets what when the real money is made.

For FoodSwift, having raised ₹1 crore at a ₹6.67 crore pre-money valuation, these terms would shape how value would be distributed in future scenarios, both good and bad.

- Would the founders maintain their ownership percentage in future rounds?

- Would investors be able to force an exit on their timeline?

- Who gets paid first if the company is acquired?

“Remember how we negotiated these terms in your term sheet?” I reminded them, pulling out the marked-up document we had finalised a month earlier. “Now we need to translate those high-level agreements into detailed, enforceable clauses that protect everyone’s interests.”

Altitude Ventures’ investment director, Vikram, who had been quietly observing until now, finally spoke up. “These provisions are not about taking advantage of founders,” he clarified. “They are about creating alignment. We all want the same thing—a successful outcome. These clauses just ensure we are on the same page about what ‘successful’ means and when it should happen.“

I nodded in agreement.

Value protection clauses are not just investor-friendly terms to be minimized, they are the rulebook for how success will be shared. I always make sure to draft it thoughtfully because it creates clarity and fairness for all parties.

As I prepare to dive into these complex provisions, you must remember that the technical details matter enormously. A single word or formula can shift millions of rupees from founders to investors or vice versa when the exit finally comes.

Let us start where most future rounds begin—with protecting against dilution when new investors come knocking with fresh capital and different valuation expectations.

From term sheet to SHA

The term sheet negotiation, which we covered extensively in our previous article “Term Sheets at Seed Stage: How to Negotiate and Advise,” laid the groundwork for value protection provisions.

But a term sheet typically uses shorthand language that leaves room for interpretation. The SHA must convert these high-level concepts into precise, enforceable mechanisms.

“Let me refresh your memory on what we still need to address from your term sheet,” I said, reviewing the key value protection terms we had not yet covered in our previous drafting sessions.

“We have already addressed the transfer restrictions, including the tag-along and drag-along rights. Now we need to focus on three critical areas that will determine how value is protected and distributed:

- anti-dilution protection,

- liquidation preference, and

- additional exit mechanisms.“

Priya looked puzzled. “I remember we discussed the 1x liquidation preference in the term sheet, but I do not recall us specifically agreeing to anti-dilution protection.“

“Good observation,” I acknowledged. “The term sheet does not explicitly mention anti-dilution protection, but it is a standard provision in most SHAs to protect investors from dilution in down rounds. We should discuss whether and how to include it.“

The investment director from Seed Capital Ventures nodded. “It is industry standard practice to include some form of anti-dilution protection, typically a broad-based weighted average approach for seed rounds. We should have this conversation now before finalizing the SHA.“

For FoodSwift, the term sheet had established:

- Liquidation Preference: 1x non-participating preference

- Pro-Rata Rights: Investors’ right to maintain ownership percentage in future rounds

- Reserved Matters: Including issuance of shares with rights senior to Preferred Shares

But it did not address anti-dilution protection or specific mechanisms for investor-initiated exits beyond the standard drag-along provisions we had already documented.

Rahul leaned forward. “So what exactly are we adding today that will affect our future fundraising and eventual exit?“

I replied by saying, “Today’s provisions are the economic playbook for three critical scenarios. First, what happens if you raise money at a lower valuation in the future? Second, who gets what if the company is sold or liquidated? And third, what happens if there’s no natural exit opportunity and investors want liquidity?“

The tricky part in drafting these clauses is finding the right balance — protecting investors without making it hard for the company to grow.

Investors want to protect themselves from risks, but if the terms are too strict, they can limit the company’s ability to operate and hurt the founders’ long-term plans.

“The standard term sheet language like ‘1x non-participating liquidation preference’ might seem straightforward,” I noted. “But implementing this in an enforceable SHA requires much more detailed language covering every possible scenario.”

For each provision, we would need to define:

- Precise triggers: What specific events activate these rights

- Calculation methodologies: Exact formulas that determine adjustments

- Procedural steps: Who does what, when, and how

- Legal compliance: Ensuring alignment with Indian company law

- Interaction effects: How these provisions affect each other

I suggested that “Let us start with anti-dilution protection, since we need to decide if and how to include it in your SHA, even though it was not explicitly covered in your term sheet.“

As we prepared to draft these critical value protection mechanisms, I reminded everyone that these were not just theoretical legal provisions—they were the rules that would determine how hundreds of millions of rupees might eventually be divided when FoodSwift achieved its ultimate success.

Anti-dilution protection

“So anti-dilution protection is not just a technical term, it is insurance for investors,” I explained, sketching a simple cap table on my notepad.

“If your next funding round happens at a lower valuation than this seed round, without anti-dilution protection, your investor would simply suffer the same dilution as everyone else.“

Rahul’s eyes narrowed. “And with anti-dilution protection?“

“Their ownership percentage gets adjusted to partially offset the impact of the down round.”

I circled Seed Capital’s 13.04% ownership on my sketch. “Think of it as retroactively lowering their original purchase price to compensate for the devaluation.”

The concept clearly made Priya uncomfortable. “But that would mean their ownership increases at our expense, right? We would be diluted even more.“

She was quick to understand the implications. Anti-dilution protection is fundamentally a zero-sum mechanism—any adjustment that preserves investor ownership must come from somewhere, and that “somewhere” is typically the founders’ stake.

“There are different flavors of anti-dilution protection,” I explained. “And they vary dramatically in how aggressive they are.“

Types of anti-dilution protection

- Full ratchet: Most aggressive, fully reprices the investor’s shares to the new lower price

- Narrow-based weighted average: Moderate, adjusts based on new shares issued only

- Broad-based weighted average: Most founder-friendly, dilutes the adjustment across all potential shares

“Let us imagine a concrete scenario,” I said. “FoodSwift raises ₹1 crore at a ₹6.67 crore pre-money valuation today. Your investor gets 13.04% ownership. Then, suppose a year later, growth is slower than expected, and you need to raise more money at a ₹5 crore pre-money valuation.“

I wrote down the numbers to demonstrate the impact:

- Without anti-dilution: The Investor’s ownership would simply dilute proportionally with the founders’ in the next round.

- With full ratchet: The investor’s effective purchase price would drop all the way to the new round’s price, significantly increasing their ownership percentage at the founders’ expense.

- With broad-based weighted average (BBWA), The investor gets some protection, but the adjustment is much more moderate.

The investment director spoke up. “For a seed-stage company like FoodSwift, we typically use broad-based weighted average protection. Full ratchet would be unusual and potentially harmful to the company’s ability to raise future rounds.”

“That’s right,” I agreed. “BBWA has become the market standard for good reason. It balances investor protection with the reality that startups often need to pivot and adjust valuations as they grow.“

I then showed them the formula that would determine the adjustment:

BBWA formula

CP2 = CP1 × (A + B) ÷ (A + C)

Where:

CP2 = New conversion price

CP1 = Original conversion price

A = Shares outstanding before new issuance

B = Total consideration from new issuance ÷ CP1

C = New shares actually issued

Seeing Rahul and Priya’s eyes glaze over at the formula, I quickly moved to a practical example.

“Let me show you how this would actually work with FoodSwift’s numbers. Assuming you have 76,700 shares outstanding after the seed round, with the investor holding 10,004 shares. If you later raise ₹1 crore at a lower ₹5 crore valuation...”

I walked through the calculation, showing how the investor’s ownership would adjust from 13.04% to roughly 14.8% in this scenario—a meaningful but not devastating adjustment.

“The key is that this happens automatically through an adjustment to the conversion price of preferred shares, not through issuing new shares immediately,” I explained.

From a legal drafting perspective, the anti-dilution provision needs to be precise and comprehensive. Here is what I proposed for FoodSwift’s SHA:

“Anti-Dilution Protection.

(a) If the Company issues any Equity Securities at a price per share less than the then-effective Conversion Price of the Series Seed Preferred Shares (a ‘Dilutive Issuance’), the Conversion Price shall be adjusted in accordance with the broad-based weighted average formula:

CP2 = CP1 × (A + B) ÷ (A + C)

Where:

- CP2 is the adjusted Conversion Price.

- CP1 is the Conversion Price in effect immediately prior to the Dilutive Issuance;

- A is the number of Equity Shares outstanding immediately prior to the Dilutive Issuance (calculated on a fully diluted basis);

- B is the aggregate consideration received by the Company in the Dilutive Issuance divided by CP1; and

- C is the number of new Equity Securities issued in the Dilutive Issuance.

(b) Excluded Issuances. The following issuances shall not trigger anti-dilution adjustments:

(i) Equity Securities issued pursuant to the approved ESOP;

(ii) Equity Securities issued upon conversion of Preferred Shares;

(iii) Equity Securities issued as dividend or distribution on Preferred Shares;

(iv) Equity Securities issued in a public offering; and

(v) Equity Securities issued in connection with equipment leasing or bank financing arrangements approved by the Board.

(c) Notice. The Company shall give the holders of Series Seed Preferred Shares written notice of any Dilutive Issuance no later than ten (10) days after the closing thereof.

(d) Clarification on Pre-Emptive Rights. Adjustments to the Conversion Price pursuant to this Clause shall not be deemed an issuance of Equity Securities for the purposes of Section 62 of the Companies Act, 2013, unless such adjustment results in the actual issuance of new Equity Securities. All shareholders agree to vote their shares as necessary to implement these adjustments when conversion occurs.”

This provision requires careful implementation under Indian company law,” I added. “Section 62(1)(c) of the Companies Act governs new share issuances to persons other than existing shareholders, requiring shareholder approval.

To avoid triggering these requirements with each adjustment, we should clarify that anti-dilution adjustments modify conversion ratios of existing securities rather than constituting new share issuances.”

I explained that the SHA should include a commitment from all shareholders to vote their shares and take all necessary actions to implement these adjustments when required, including amending the Articles of Association if necessary.

Priya still looked concerned. “What’s to prevent an investor from deliberately blocking future funding to trigger anti-dilution?“

That was a good question.

I responded by saying, “That is why the carve-outs in section (b) are so important. They exempt certain strategic issuances from triggering anti-dilution. Additionally, this is where having a broad-based formula rather than full ratchet is critical—it reduces the incentive for such behavior.“

With the anti-dilution protection framework established, we were ready to move on to what happens when the company achieves a successful exit, or faces liquidation.

Exit mechanisms

“Raising capital is just the beginning of the journey. Investors also need to know how and when they will get their money back—hopefully with a healthy return.” I told Rahul and Priya.

While the term sheet had touched on drag-along rights (which we covered in Part 2), it did not fully address the range of exit mechanisms that should be included in a comprehensive SHA.

“All investors eventually need liquidity,” I explained. “For FoodSwift, there are three primary exit pathways we need to document in the SHA.“

I sketched a simple diagram showing three routes:

- IPO: The company goes public

- M&A: The company is acquired or merges with another entity

- Secondary Sales: Investors sell shares to other private investors

“But what if none of these happen naturally?” asked the investment director from Seed Capital. “Many startups reach a comfortable size but never go public or get acquired.“

This led perfectly into what I call “forced exit” provisions — clauses that let investors push for a sale or IPO if the company does not reach one on its own within a reasonable time.

“There are several types of provisions we should consider, including,” I explained. “The most common for seed-stage deals are registration rights, put options, and sale initiation rights.“

Rahul looked concerned. “You are saying investors could force us to sell the company after a certain time period?“

“They could initiate a process,” I clarified. “But with appropriate protections for all parties. Remember, investors are not looking to harm the company—they just need eventual liquidity for their fund economics to work.“

“How do these exit mechanisms interact with the drag-along rights we discussed in Part 2?” Priya asked thoughtfully. “An excellent question that many founders miss,” I responded.

“These mechanisms can work together but operate on different triggers,” I explained that drag-along rights typically require a specific threshold of shareholders (often including both investors and founders) to approve a sale, while sale initiation rights allow investors to begin a process without founder approval. To address this, I added clause (b) iv.

Nevertheless, for FoodSwift’s SHA, I proposed a balanced approach:

“Exit Rights.

(a) IPO Rights. If the Company proposes to undertake an IPO, the Investors shall have the right to:

(i) Include their Shares in such offering on a pro-rata basis (subject to underwriter limitations); and

(ii) Receive customary registration rights including piggyback rights for future registrations.

(b) Sale Initiation. After the 7th anniversary of the Effective Date, if the Company has not completed an IPO or a Liquidity Event, Investors holding at least 70% of the Series Seed Preferred Shares may, by written notice to the Company, require the Company to initiate a process to explore strategic alternatives, including:

(i) Engaging a reputable investment banker to conduct a sale process;

(ii) Providing necessary information to potential acquirers; and

(iii) Considering in good faith any reasonable acquisition offer resulting from such process.

(iv) Interaction with Drag-Along Rights. Any sale process initiated pursuant to this Clause shall proceed in accordance with the process outlined herein. However, the actual consummation of any transaction resulting from such process may require implementation of the drag-along provisions set forth in Clause [X] of this Agreement, which shall apply according to their terms. For clarity, the initiation of a sale process does not automatically trigger drag-along rights, which require separate approval thresholds as specified in Clause [X]

(c) Put Option. After the 7th anniversary of the Effective Date, if no Liquidity Event has occurred, each Investor shall have the option (but not the obligation) to require the Company to repurchase their Shares at a price equal to the Fair Market Value, subject to:

(i) The Company’s having sufficient legally available funds;

(ii) Such repurchase not violating any applicable laws or regulations; and

(iii) Such repurchase not materially impairing the Company’s financial condition.

(iv) FEMA Compliance. As Seed Capital includes foreign investment, any repurchase under this put option shall comply with the pricing guidelines prescribed under the Foreign Exchange Management (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, and shall be subject to applicable approvals from the Reserve Bank of India. The Company and all Shareholders shall cooperate to obtain any required regulatory approvals.

(d) Sale Cooperation. All Shareholders shall cooperate in good faith and take all necessary actions to facilitate any Exit Event, including voting their shares in favor of such transaction, executing relevant documentation, providing representations and warranties, and taking other actions reasonably necessary to complete such transaction.

(e) Valuation Process. In the event the Fair Market Value must be determined for purposes of this Agreement, the following process shall apply:

(i) Timeline: The Fair Market Value shall be determined within thirty (30) days of the triggering event (such as exercise of the put option).

(ii) Valuer Selection: Fair Market Value shall be determined by an independent valuer mutually appointed by the Investors and the Company within ten (10) days of the triggering event. If the parties fail to agree on a valuer within this period, each shall appoint one valuer within the following seven (7) days, and these two valuers shall jointly appoint a third valuer within seven (7) days thereafter, whose determination shall be final and binding.

(iii) Cost Allocation: The costs of the valuation shall be borne equally by the Company and the party requiring the valuation, unless otherwise agreed.

(iv) Valuation Standards: The valuation shall be conducted in accordance with generally accepted valuation methodologies appropriate for technology companies at similar stages, and in compliance with any applicable regulatory requirements.”

Priya studied the provision carefully. “Seven years seems like a long time. Why that specific timeframe?“

“It is a standard industry timeframe that balances everyone’s interests. It gives you plenty of time to build value, while still providing investors a liquidity pathway within the typical 10-year lifespan of most venture funds.” I explained.

“And what about this Fair Market Value determination?” Rahul asked. “That seems potentially contentious.“

“You are right to focus on that,” I nodded. “The valuation mechanism is critical. That is why we have included a balanced approach with mutually appointed valuers. However, I should note that these put options often serve more as a forcing function to drive other exit alternatives rather than being exercised directly.“

I also explained the regulatory considerations for exit mechanisms under Indian law:

“The regulatory treatment of put options varies significantly depending on whether the investor is domestic or foreign,” I explained.

“For Seed Capital Ventures, which has foreign investment, we must comply with the Foreign Exchange Management Act (FEMA) regulations. Under the FEMA (Non-Debt Instruments) Rules, 2019, put options are permitted for foreign investors, but the exit price cannot exceed the fair market value determined according to prescribed pricing guidelines, typically using Discounted Cash Flow valuation for unlisted companies.“

“Additionally, if FoodSwift eventually pursues an IPO, SEBI regulations impose lock-in periods for pre-IPO investors, typically 36 months, depending on whether they are classified as promoters or non-promoters.“

The investment director added, “From our perspective, the most important aspect is having a clearly defined process if there is no natural exit within a reasonable timeframe. The specific mechanism—whether it is a put option, sale process, or something else—is less important than having clarity on the timeline and process.”

I reminded everyone that the exit provisions need to work in harmony with the liquidation preference we would be discussing next, as they both govern how proceeds are distributed when investors ultimately exit the company.

“With these exit mechanisms properly documented,” I concluded, “We have established not just how decisions are made today, but how value will be realised for all shareholders tomorrow. Now let us address how that value gets distributed when an exit actually occurs.“

Liquidation preference

“If you asked one hundred startup founders what liquidation preference means, I bet ninety would say it is about bankruptcy,” I told Rahul and Priya with a slight smile. “But that is not actually its primary purpose.“

The FoodSwift founders exchanged uncertain glances. Like many entrepreneurs, they had signed the term sheet agreeing to a “1x non-participating liquidation preference” without fully understanding the mechanics and implications.

“Liquidation preference determines who gets paid what—and in what order—when the company is sold, merged, or actually liquidated,” I explained. “It is the economic bedrock of venture capital investing.“

The investment director nodded in agreement. “It is our safety net if things do not go as planned. In exchange for taking early risk, we get a guaranteed minimum return before the common shareholders receive proceeds.“

I grabbed a fresh sheet of paper and drew a simple waterfall diagram. “Let me show you exactly how this works with your agreed 1x non-participating preference.“

The diagram illustrates two scenarios:

Scenario 1: FoodSwift sells for ₹5 crores (less than 5x the investment amount)

- Seed Capital gets their ₹1 crore back first (1x preference)

- Remaining ₹4 crores go to all shareholders proportionally as if converted to common shares

- Result: Seed Capital gets ₹1 crore + (13.04% × ₹4 crores) = ₹1.52 crores

Scenario 2: FoodSwift sells for ₹20 crores (high-multiple exit)

- Seed Capital has two options:

- Take ₹1 crore (1x preference) + nothing else (non-participating), OR

- Convert to common shares and take 13.04% × ₹20 crores = ₹2.6 crores

- Rational choice: Option 2 (convert to common)

- Result: Seed Capital gets ₹2.6 crores, founders get the remaining ₹17.4 crores

“In a successful outcome, your investor will simply convert to common shares and share proportionally in the proceeds,” I explained. “The preference only matters in moderate or disappointing exit scenarios.“

I then highlighted why the specific terms “1x” and “non-participating” were so important.

“The ‘1x’ means they get their original investment amount back first, not 2x or 3x, which would be more aggressive. And ‘non-participating’ means after getting that preference amount, they do not also get to participate again as common shareholders—they have to choose one or the other.“

Rahul looked relieved. “That seems fair. They get their money back first, but in a big exit, we all share proportionally.”

“Exactly,” I confirmed. “There are many more aggressive structures out there. A ‘2x participating preference with multiple’ would mean they get twice their money back first, THEN they also share proportionally in the remaining proceeds, and potentially with a multiple applied to their participation.“

I then turned to the actual drafting of this critical provision for the SHA:

“Liquidation Preference.

(a) Liquidation Events. In the event of any:

(i) Liquidation, dissolution, or winding up of the Company;

(ii) Merger, consolidation, or amalgamation resulting in a change of control;

(iii) Sale, lease, transfer, exclusive license or other disposition of all or substantially all of the Company’s assets;

(iv) Sale or exchange of more than 50% of the Company’s outstanding shares; or

(v) Any other transaction where control of the Company is transferred (each, a ‘Liquidation Event’), the assets or proceeds available for distribution shall be distributed in accordance with this provision.

(b) Distribution Waterfall. Upon the occurrence of a Liquidation Event, available proceeds shall be distributed in the following order:

(i) First, the holders of Series Seed Preferred Shares shall be entitled to receive, prior and in preference to any distribution to holders of Equity Shares, an amount per share equal to the Original Investment Amount (₹1,00,00,000 in aggregate) (the ‘Preference Amount’).

(ii) After payment of the Preference Amount in full, any remaining proceeds shall be distributed among all shareholders (including holders of Series Seed Preferred Shares if they would receive more than the Preference Amount on an as-converted basis) pro rata according to their respective shareholdings on an as-converted basis.

(c) Conversion Option. Prior to any Liquidation Event, each holder of Series Seed Preferred Shares may elect to:

(i) Receive the Preference Amount; or

(ii) Convert their Preferred Shares into Equity Shares and participate in proceeds distribution on an as-converted basis, whichever would result in the greater amount.

(d) Deemed Liquidation. Any transaction or series of related transactions that constitute a change of control shall be treated as a Liquidation Event unless holders of at least 70% of the Series Seed Preferred Shares elect otherwise in writing.

(e) Distributions In-Kind. In case of a distribution of assets other than cash, the value of such assets shall be determined by an independent valuer selected in accordance with the procedure set forth in Clause [X].”

“This is quite comprehensive,” Priya noted, studying the language. “But what is the purpose of the ‘Deemed Liquidation’ provision?“

“Good catch,” I replied. “That prevents a technical workaround where the company could be acquired through a series of smaller transactions that would not formally trigger the liquidation preference. It is a standard protection to ensure the economic rights work as intended, regardless of transaction structure.“

I also highlighted the Indian legal considerations for liquidation preferences.

“Under section 53 of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code 2016, which governs the distribution of assets in a winding-up, there’s a specified order of priority for different types of creditors and shareholders. Our liquidation preference needs to work within this statutory framework.“

“Importantly, while these preferences are fully enforceable in private sale transactions through contractual arrangements, in an actual bankruptcy liquidation, they might be subject to statutory distribution rules. That is why we include both statutory liquidation and ‘deemed’ liquidation events like mergers and acquisitions.”

To help the founders understand the real-world impact, I created a simple table showing how the proceeds would be distributed across different exit values:

| Exit Value | Investor Share (with 1x non-participating) | Founders’ Share |

| ₹3 crores | ₹1 crore (33.3%) | ₹2 crores (66.7%) |

| ₹7.67 crores | ₹1 crore + ₹0.87 crores = ₹1.87 crores (24.4%) | ₹5.8 crores (75.6%) |

| ₹15 crores | ₹1.96 crores (13.04%) | ₹13.04 crores (86.96%) |

| ₹50 crores | ₹6.52 crores (13.04%) | ₹43.48 crores (86.96%) |

“As you can see, the preference matters most in modest exits. Once the company achieves significant value, everyone simply shares proportionally based on their ownership percentage.” I said.

Rahul nodded thoughtfully. “So this is why investors focus so much on liquidation preferences—it protects their downside while still allowing unlimited upside.“

“Precisely,” I confirmed. “And the ‘1x non-participating’ structure you have agreed to is the most balanced approach. It provides reasonable downside protection for investors without creating misaligned incentives or unfairly disadvantaging founders in moderate success scenarios.“

With the liquidation preference properly documented, we had put in place the final major economic provision that would govern how value is distributed when FoodSwift eventually reaches its exit.

Implementation through Articles of Association

“There is one critical aspect of implementing these provisions that we need to discuss,” I said after we had worked through the key economic terms.

“For these provisions to be fully enforceable, especially against future shareholders or in statutory proceedings, we need to reflect them in the Company’s Articles of Association (AoA).” Rahul looked puzzled.

“I thought the SHA was sufficient by itself?” “The SHA creates contractual obligations between the current parties, but under Indian company law, particularly Sections 14 and 10 of the Companies Act, 2013, the Articles of Association govern the company’s internal management and are binding on the company and all shareholders, present and future,” I explained.

“Without corresponding provisions in the AoA, some of these rights might not be enforceable against the company itself or against future shareholders who aren’t parties to the SHA.”

I recommended adding the following provision to ensure proper implementation:

Amendment of Articles of Association.

Within 30 days of executing this Agreement, the Shareholders shall vote their shares and take all necessary actions to amend the Company’s Articles of Association to incorporate the provisions of this Agreement, including but not limited to the anti-dilution protections, liquidation preferences, transfer restrictions, and exit rights. The Shareholders agree that in case of any conflict between this Agreement and the Articles of Association, they shall amend the Articles to eliminate such conflict.

“This provision creates a legal obligation to update your AoA, ensuring these carefully negotiated protections have maximum legal effect,” I told them.

“It’s particularly important for the liquidation preference and anti-dilution provisions, which directly affect share rights.”

Conclusion

As we wrapped up our discussion of value protection mechanisms, I could see a new level of understanding in Rahul and Priya’s eyes.

What had started as abstract contractual concepts had transformed into practical tools they could visualize affecting FoodSwift’s future.

“We have now addressed the three fundamental economic engines of your SHA,” I explained, gathering up my notes. “Anti-dilution protection ensures fair treatment in future funding rounds. Exit mechanisms create pathways to liquidity for all shareholders. And liquidation preference establishes clear rules for distributing proceeds when that exit arrives.“

These provisions completed our work on the commercial and economic aspects of FoodSwift’s shareholders’ agreement. Over our three drafting sessions, we had established:

- Control framework (Part 1): Who makes which decisions through board composition, reserved matters, and voting rights

- Protective boundaries (Part 2): How shares can be transferred, founder commitments, and information rights

- Value protection (Part 3): Economic terms that govern future fundraising, exits, and proceeds distribution

Rahul leaned back in his chair. “So are we done now? Is the SHA complete?“

“Almost,” I replied with a smile. “We have built the commercial architecture, but there is one final piece still missing—the legal infrastructure that makes all of these provisions enforceable.“

“What do you mean?” Priya asked. “Are not these clauses already legally binding once we sign the SHA?“

“In theory, yes,” I explained.

“But without proper dispute resolution mechanisms, amendment procedures, and termination provisions, even the most carefully crafted commercial terms can crumble when faced with real-world conflicts.“

The founders exchanged glances, clearly ready to wrap up the drafting process but recognising the importance of this final step.

“Think of it this way,” I continued.

“We have designed a beautiful house with all the rooms and features you need. But without proper plumbing, electrical, and structural support, it will not actually function when you move in. The legal mechanics we will address next are what make your SHA livable and durable for years to come.“

In our fourth and final session, we would address:

- Dispute Resolution: How disagreements will be handled, including arbitration procedures and governing law

- Amendment & Waiver: The process for changing SHA terms as the company evolves

- Termination: When and how the SHA ends, and which provisions survive

- Miscellaneous Legal Provisions: The seemingly boilerplate clauses that can make or break enforceability

“Once we have addressed these elements,” I assured them, “you will have a comprehensive, enforceable SHA that can guide FoodSwift through its entire lifecycle—from this seed round all the way to your eventual successful exit.“

With that, we scheduled our final drafting session, ready to complete the journey from term sheet to a full-fledged shareholders’ agreement that would stand the test of time and protect everyone’s interests through FoodSwift’s growth journey.

Coming next in part 4: Finalising the SHA

In our final installment, I will address how to make your SHA terms enforceable, adaptable, and legally sound, helping you avoid court drama later. We will cover essential dispute resolution mechanisms, amendment procedures, termination triggers, and those seemingly mundane but critically important “boilerplate” provisions that can make or break your agreement when conflicts arise.

You will learn how to select the right arbitration venue, draft provisions that survive SHA termination, and avoid common legal drafting mistakes that have sunk many otherwise solid agreements. By the end, you’ll have all the tools needed to draft a comprehensive SHA for any early-stage startup.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications