Learn how to file complaints against misleading food labels, pursue consumer commission cases, or escalate to criminal proceedings. This article provides practical steps to gather evidence and ensure compliance, protecting your rights and brand. So, whether you are a consumer or food business owner, or a legal professional in the healthcare or consumer sector, this guide will be useful.

Table of Contents

Introduction

It was a typical rainy day in Mumbai. I saw the rain drummed against the windows of my chamber as I sorted through the day’s case files. At half past seven, most of the clerks had left, leaving behind only the familiar smell of old law books and the soft hum of the air conditioner. I was just about to call it a day when my junior, Ashima, knocked on my door.

“Sir, sorry to disturb you this late,” she said, clutching a thick file against her chest. “But I have a client meeting tomorrow morning, and I am completely lost.”

I gestured to the chair across from my desk. “What is the matter?”

She opened the file with nervous fingers. “Mrs. Sharma bought these ‘sugar-free’ cookies for her diabetic husband from a premium health food store. Cost her Rs. 800 for a 200 gms pack.” Ashima’s voice grew more animated as she spoke. “Three hours after he ate them, her husband was rushed to the hospital with blood sugar levels through the roof.”

I leaned back in my chair, already sensing where this was heading. “Let me guess: the cookies were not sugar-free?”

“Exactly! The laboratory report shows significant amounts of hidden sugars. Fructose, corn syrup, the works.” She pulled out a crumpled package from the file. “Look at this label: ‘SUGAR-FREE’ in bold green letters, with a tiny asterisk leading to microscopic text at the bottom.”

I picked up the package, studying it under my desk lamp. The fine print was barely visible even with my reading glasses. “And Mrs. Sharma wants to file a consumer complaint?”

“Yes, but sir…” Ashima hesitated. “I have drafted a basic complaint for the district consumer forum, but I feel like I am missing something. The medical bills are Rs. 30,000, but she is talking about the emotional trauma, the breach of trust. And honestly, I don’t even know if this is just a consumer forum matter or if it goes deeper.”

I smiled, remembering my early days when every case felt like navigating uncharted territory. “Ashima, sit down. Let me tell you something about food labelling cases: they are like icebergs. What you see on the surface is just the beginning.”

She pulled out her notepad, pen poised to capture every word.

“First thing you need to understand,” I continued, “is that food labelling violations in India are not just consumer disputes. They sit at the intersection of multiple legal frameworks – consumer protection, food safety regulations, criminal law, and sometimes even constitutional rights.”

Her eyes widened. “Constitutional rights? For cookies?”

“Think about it this way,” I said, warming to the topic. “When a company puts ‘sugar-free’ on a package, they are not just making a marketing claim. They are entering into a contract with every consumer who reads that label. For a diabetic person, that label could be the difference between a normal day and a medical emergency. The law recognises this responsibility.”

I opened my laptop and pulled up the FSSAI website. “Let me show you the complete picture. Mrs. Sharma’s case is not unique. We get at least two such cases every month. The problem is that most lawyers, even experienced ones, treat these as simple consumer complaints. But look at this…” I turned the screen toward her.

“The Food Safety and Standards Authority handles thousands of mislabelling complaints annually. Some result in simple warnings, others lead to product recalls worth crores, and a few escalate to criminal prosecution. The difference lies in understanding which legal avenue suits your case best.”

Ashima scribbled furiously. “So, for Mrs. Sharma’s case, what would you advise?”

“Ah, that is where it gets interesting,” I said, reaching for my tea that had long gone cold. “We have multiple options, and the strategy we choose depends on what Mrs. Sharma really wants to achieve. Does she want compensation? Does she want to ensure this does not happen to other diabetic patients? Or does she want to make an example of this company?”

“I think she wants all three,” Ashima replied.

“Then we need to understand the entire legal ecosystem.” I pulled out a fresh legal pad. “Let me walk you through this systematically, because food labelling law in India is like a three-dimensional chess game. Every move you make in one forum affects your options in others.”

Over the next two hours, as the rain continued its steady rhythm outside, I shared with Ashima everything I had learned about food labelling cases over seven years of practice. From regulatory complaints that could shut down production lines, to consumer forum proceedings that could award punitive damages, to criminal cases that could land company executives in jail.

“The beauty of food labelling law,” I told her as we wrapped up, “is that it is consumer protection in its purest form. Every case has the potential to create industry-wide changes. Mrs. Sharma’s sugar-free cookie case? It could become the precedent that forces clearer labelling across the entire health food industry.”

Ashima looked up from her notes, which now covered several pages. “This is fascinating, sir. I had no idea food labelling cases could be so complex.”

“Most people don’t,” I replied. “That is why companies get away with misleading labels for years before someone like Mrs. Sharma decides to fight back. But once you understand the legal framework, these cases become incredibly powerful tools for systemic change.”

“So tomorrow’s meeting with Mrs. Sharma…”

“Tomorrow, you will explain to her not just how to file a consumer complaint, but how to navigate the entire legal landscape. You will show her that her case is not just about Rs. 20,000 in medical bills, it is about holding a multi-crore company accountable for potentially endangering thousands of diabetic consumers.”

As Ashima gathered her files to leave, she paused at the door. “Sir, one last question. How do we ensure our complaint is bulletproof?”

“That is what we are going to discuss right now. Let me show you the anatomy of a winning food labelling complaint, and more importantly, help you understand when to use each of the six different legal remedies available to consumers like Mrs. Sharma.”

She settled back into her chair, ready for the detailed journey ahead.

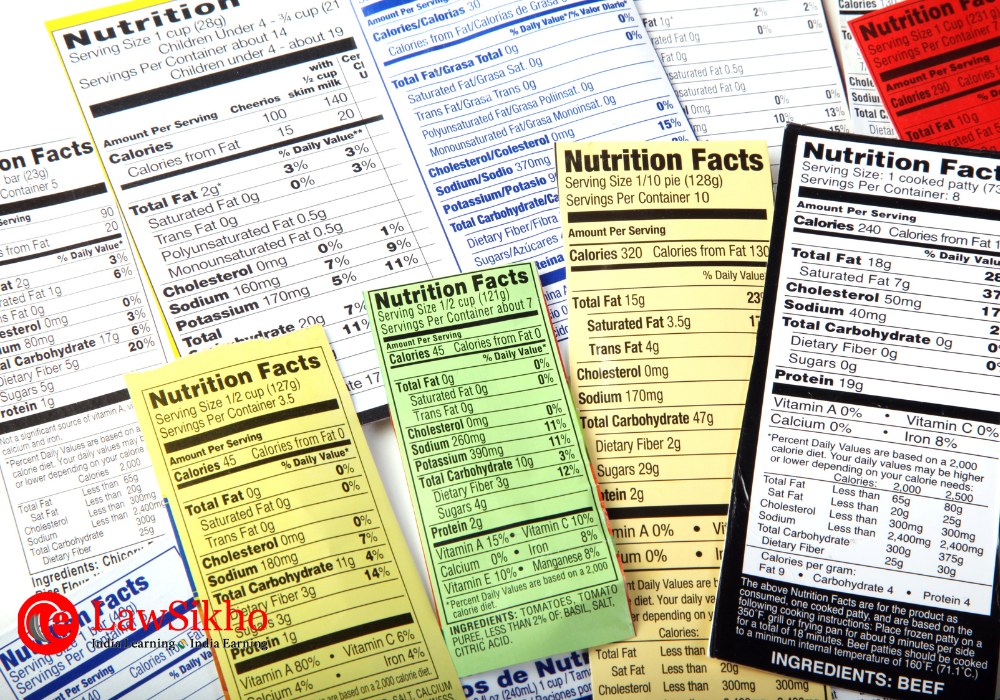

What is food labelling, and why does it matter beyond marketing?

“Before we dive into the legal remedies,” I told Ashima, “you need to understand why food labelling cases are now treated so seriously by Indian courts.”

I opened Mrs. Sharma’s file again. “Look at this medical report. Her husband’s blood sugar spiked from 140 mg/dl to 380 mg/dl within three hours. For a diabetic patient, that is not just an inconvenience: it is potentially life-threatening.”

“The courts have repeatedly held that food labels create legitimate consumer expectations. When someone with diabetes sees ‘sugar-free’ on a package, they are not just making a purchase decision: they are making a health decision based on trust.”

“So the courts treat food labelling as more than just marketing?”

“Exactly. From a legal perspective, every claim on a food package is a representation that the manufacturer warrants to be true. Break that warranty, and you are liable under multiple laws simultaneously.”

I drew a quick diagram on my notepad. “Think of it this way, when Mrs. Sharma bought those cookies, three separate legal relationships were created:

- Consumer protection relationship: The company promised a sugar-free product in exchange for payment

- Food safety relationship: The company certified that the product met safety standards for diabetic consumption

- Trust relationship: The company assumed responsibility for accurate health-related information

Violate any one of these, and different legal remedies kick in.”

India’s statutory framework

“Now, let me explain the legal architecture,” I continued, pulling up a flowchart I had created for my easy reference. “Food labelling law in India rests on three main pillars.”

A. Primary food safety laws

- Food Safety and Standards Act, 2006 (FSS Act)

“This is your primary weapon,” I explained. “The FSS Act covers everything from farm to fork. For Mrs. Sharma’s case, section 23 is crucial, it mandates that food business operators ensure accurate labelling.”

I showed Ashima the relevant section on my screen. “Look at this language: ‘No person shall manufacture, distribute, sell or expose for sale any article of food which is misbranded.’ The definition of ‘misbranded’ includes any food that bears false or misleading information.”

“What powers does FSSAI have?” Ashima asked.

“Extensive ones. They can conduct raids, recall products, suspend licenses, and impose penalties up to Rs. 10 lakhs. But more importantly for our case, they can issue public notices about the violation, which often forces companies to settle rather than face negative publicity.”

“These regulations are incredibly detailed,” I continued. “They specify exactly what must be on every food package: ingredients in descending order, nutritional information, allergen warnings, everything.”

I opened the regulation PDF. “For sugar-free claims, Regulation 2.2.4 is specific: products can only be labelled ‘sugar-free’ if they contain less than 0.5g of sugar per 100g or 100ml. Mrs. Sharma’s cookies contained 8.3g per 100g.”

“This is where companies often trip up,” I explained. These regulations govern health claims and nutritional claims. They require scientific substantiation for any health-related statement.

B. Consumer protection framework

“This is probably where Mrs. Sharma’s case will be strongest,” I told Ashima. “The 2019 Act has powerful provisions against unfair trade practices and misleading advertisements.”

I highlighted the relevant section. “Section 2(47) defines ‘unfair trade practice’ to include misleading information about the nature, substance, or quality of goods. Mrs. Sharma’s case fits perfectly.”

“What about jurisdiction?” Ashima asked. “Where should we file?”

“Good question. Under the updated Act, District Consumer Commissions handle claims up to Rs. 1 crore, State Commissions handle Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 10 crores, and the National Commission handles claims above Rs. 10 crores.”

“Don’t overlook this,” I cautioned. “It covers the accuracy of weights, measures, and quantity declarations. If there are any discrepancies in net weight or MRP, it provides additional grounds for complaint.”

C. Criminal law protection

- Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita, 2023 (Sections 274-278)

“Now we are entering serious territory,” I said, my tone becoming more grave. “These sections deal with adulteration and sale of noxious food. Section 274 covers whoever adulterates any article of food or drink, section 275 specifically covers selling food that is harmful due to mislabeling, section 276 deals with drug adulteration, section 277 covers selling noxious drugs, and section 278 addresses misrepresentation of drugs.”

Ashima looked concerned. “Would Mrs. Sharma’s case qualify for criminal prosecution?”

“Potentially, yes. If we can prove that the company knew their labelling was false and that it could harm diabetic consumers, we could pursue criminal charges under section 275. The key is establishing mens rea (guilty intention).”

I leaned forward. “Remember the Patanjali case from last year? The Supreme Court came down heavily on misleading health claims in their products. Justice Kohli and Justice Amanullah specifically noted that companies making health claims without scientific backing could face prosecution under these very sections. The Court observed that such violations do not just cheat consumers financially, they endanger public health.”

- Bureau of Indian Standards Act, 2016 (Sections 14, 15, 17)

“This Act mandates quality standards and certification for specific food categories,” I explained. “Section 14 requires ISI mark compliance for notified food products, section 15 deals with penalties for non-compliance, and section 17 covers enforcement powers. If Mrs. Sharma’s cookies fall under any notified category, this gives us another legal avenue.

Understanding the mislabelling spectrum: When good intentions meet legal reality

“You know what is fascinating about food labelling cases?” I asked Ashima, settling back in my chair. “Most violations don’t come from deliberately evil companies trying to poison people. They come from well-intentioned businesses that simply don’t understand the legal complexities.”

I opened another case file from my drawer. “Let me tell you about my client, Akash. CEO of GreenHarvest Foods, an organic food startup. Brilliant guy, genuinely cares about health and nutrition. But three months ago, he called me at 11 PM, completely panicked.”

“What was it regarding?” Ashima asked.

“FSSAI had served them a notice. Their ‘organic quinoa bars’ were flagged for mislabelling. They could not use ‘superfood’ on packaging without substantiation under the Advertising and Claims Regulations, 2018. Worse, their ‘high protein’ claim violated the law: they had 8 grams per serving but needed at least 10.8 grams per 100g to qualify.”

I could see Ashima taking detailed notes. “The poor guy was devastated. ‘We put our hearts into this company,’ he told me. We genuinely source the best ingredients. How did we end up here?”

“That conversation happens more often than you would think. Let me walk you through the six most common ways honest companies like Akash’s end up in legal trouble.”

1. The “High Protein” Trap

“Akash genuinely believed their calculations were correct. Their founder later told me, ‘We calculated protein content based on our supplier’s data. We never thought to verify it independently or check FSSAI’s specific requirements.”

I pulled up the Advertising and Claims Regulations on my laptop. “Here is the reality check: For ‘high protein’ claims, you need at least 20% of the Nutrient Reference Value per 100g or 100ml. The NRV for protein is 54g per day for adults, so that is 10.8g per 100g minimum.”

“Their bars contained 8g of protein per serving, but they claimed 15g. When the consumer forum imposed Rs. 25 lakh in penalties under section 35 of the Consumer Protection Act 2019, the judge noted something crucial: ‘Mathematical errors that mislead health-conscious consumers cannot be dismissed as innocent mistakes.'”

“What is Akash doing now?” Ashima asked.

“Smart learning. He now tests every batch independently and maintains detailed calculation sheets. Costs him Rs. 15,000 monthly, but it is way cheaper than a Rs. 25 lakh penalty.”

2. The ingredient switcheroo

“This one still gives me chills,” I said, opening another file. “A premium chocolate brand learned this lesson the hard way. To cut costs, they substituted some cocoa with cheaper vegetable fat. Sounds like a business decision, right?”

“What went wrong?”

“Their procurement team made the change to improve margins, but nobody updated the legal team or the labels. Customers buying ‘pure cocoa’ chocolate were getting a blend. The courts did not see this as cost optimisation: they saw it as deliberate deception.”

I showed Ashima the judgment. “Ingredient lists must be in descending order by quantity. Any substitution needs label updates and FSSAI approval. The company faced criminal charges under section 275 of BNS 2023 for selling noxious food, because they hadn’t disclosed the change to consumers.”

3. The organic illusion

“This case from last year still haunts me,” I said, pulling up news clippings. “A cooking oil brand built its entire marketing around being ‘100% natural.’ Their CEO genuinely believed they were selling natural products because their suppliers assured them of natural extraction methods.”

“But FSSAI’s investigation revealed the oils were chemically extracted, not naturally processed. Worse, the company had fake organic certifications and backdated documentation. The penalties? Rs. 2 crore fine, criminal cases against three directors and a recall of 50,000 units.”

“The lesson here,” I emphasised, “is that organic certification requires continuous NPOP or PGS-India compliance, not just a certificate on the wall.”

4. The allergen nightmare

“Here is where food labelling intersects with life and death,” I said, my voice becoming serious. “A bakery proudly advertised ‘nut-free’ cakes for customers with allergies. They genuinely tried to maintain separate preparation areas and equipment.”

“But?” Ashima prompted.

“Trace amounts of almonds from cross-contamination ended up in a cake, causing a customer’s anaphylactic shock. The Rs. 15 lakh lawsuit was not just about medical bills, it was about broken trust.”

I showed her the relevant regulation that mandates allergen labelling. But it is not just about intentional ingredients. Even potential cross-contamination must be disclosed.”

“The court applied the ‘reasonable expectation’ test: if you claim your product is safe for people with allergies, you are liable for any allergen presence, even trace amounts, unless you have disclosed the possibility.”

5. When dots matter more than you think

“This case became national news,” I said, pulling up newspaper clippings. “Remember the Maggi controversy? But there was another case, a popular instant noodle brand used the green dot (vegetarian symbol) but included beef flavouring in their seasoning.”

Ashima’s eyes widened. “That is a serious violation.”

“The company’s quality team had focused on the noodles themselves, not realising that flavouring additives could violate vegetarian labelling.”

“The legal storm was massive:

- Rs. 10 lakh fine under the Consumer Protection Act, 2019

- Criminal charges for outraging religious feelings

- FSSAI action across multiple states”

“Here is what made it different,” I explained. “Vegetarian/non-vegetarian mislabelling is not just about food laws, it touches constitutional protections under Article 25 of the Constitution. Courts treat these violations as attacks on fundamental rights, not just commercial mistakes.”

6. When the extended shelf life shortens, the business life

“This final case shows how systematic violations escalate quickly,” I said. “A dairy company thought they found a clever solution to reduce waste, reprinting labels with extended expiry dates on products nearing expiration.”

“That sounds like fraud,” Ashima said.

“Exactly what the courts thought. FSSAI’s enforcement team used sophisticated analysis, cross-referencing production records with distribution timelines. They caught the manipulation within three months.”

“The consequences under various sections:

- Rs. 50 lakh fine

- FSSAI license suspension for six months

- Class action lawsuit from 10,000 consumers

- Criminal charges”

“What made it worse was that courts treated this as intentional fraud. The systematic nature showed premeditation, eliminating any possibility of claiming innocent error.”

Legal remedies available to consumers

“Now comes the exciting part,” I told Ashima, opening a fresh notepad. “Mrs. Sharma has multiple legal weapons at her disposal. The key is choosing the right combination for maximum impact.”

A. Regulatory complaints

- Filing with FSSAI

“The FSSAI complaint mechanism works faster than most people expect,” I explained, “but it requires strategic presentation.”

I outlined the step-by-step process:

“Online complaint filing process:

- Visit the FSSAI consumer grievance portal

- Register as a consumer, Consumer Grievance Rules

- Select ‘Package Foods’ for labelling issues

- Upload evidence – photos, purchase receipts, medical records

- Submit for investigation”

“Timeline and powers: Most FSSAI investigations conclude within 60-90 days. The Food Safety Officers have the power to collect samples, conduct inspections, and recommend action to the designated officer.

“Here is what many lawyers miss,” I added. “FSSAI complaints often trigger parallel investigations by Legal Metrology and Consumer Affairs departments under various state acts. Prepare for multi-front regulatory scrutiny.”

B. Consumer forum proceedings

“The Consumer Protection Act’s three-tier structure requires forum selection,” I explained.

“District Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (claims up to Rs. 1 crore):

- Faster proceedings (6-8 months average)

- Local enforcement advantages

- Direct consumer-manufacturer interaction”

“State Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (Rs. 1 crore to Rs. 10 crores):

- More sophisticated legal procedures

- Precedent-setting potential

- Appeals mechanism

“National Consumer Disputes Redressal Commission (Section 58 – above Rs. 10 crores):

- Supreme Court-level proceedings

- Industry-wide impact decisions

- Comprehensive remedy powers”

C. Civil suits

“Civil suits under section 9 of the Code of Civil Procedure become necessary when:”

I enumerated on my fingers: “Damages exceed consumer forum jurisdiction, multiple legal violations require comprehensive adjudication, or class action proceedings of the Consumer Protection Act become necessary.”

D. Criminal proceedings

“Criminal proceedings carry enormous reputational risks but offer the strongest deterrent effect,” I warned.

“Three Routes Available:

- Police complaint/FIR: Approach the local police with evidence of labelling violations.

- Magistrate complaint: If police refuse to file a complaint, file a private complaint directly before the Magistrate”

- Through Food Safety Officer: If the laboratory report shows substandard or misbranded products, after the Designated Officer’s approval, a complaint is lodged.

E. Class action suits

“Section 35 of the Consumer Protection Act, 2019, provides for class action suits with specific eligibility criteria,” I explained.

“Requirements:

- Numerous people have the same interest

- Common questions of law or fact

- Adequate representation by class representatives

- Class action is the appropriate method for resolution”

“Remember the Patanjali case (Indian Medical Associations & Anr. vs. Union of India & ors. – WP(C) No. 645/2022)?” I asked. “When the Supreme Court was dealing with their misleading advertisements, Justice Hima Kohli and Justice Amanullah observed that such violations affect thousands of consumers simultaneously. That is exactly when class action becomes powerful.”

F. Additional reporting options

“For Advertising Issues: File with Advertising Standards Council of India for misleading advertisements”

“Anonymous complaints: FSSAI allows anonymous complaints, though providing contact details helps them seek additional information”.

Complaint drafting strategy

“Now, let us talk about crafting a complaint that judges will take seriously,” I said, pulling out some successful complaints from my files.

“Here is what separates winning complaints from weak ones:”

- Essential elements

- Factual foundation: “Start by establishing the manufacturer’s specific duty. Do not just say they violated the law: explain exactly what duty they owed to Mrs. Sharma as a diabetic consumer.”

- Specific labelling violations with documentary evidence: “Reference exact regulations violated,

- Causation linkage: Connect the mislabelling directly to Mrs. Sharma’s harm. Use medical expert testimony to substantiate your averments.

- Quantified loss calculations: “Include immediate medical costs, future monitoring expenses, and emotional distress.”

- Reliefs sought: Mrs. Sharma can seek the following reliefs:

- Product recall, public warning notice, corrective advertising, implementation of strict labelling protocols, and FSSAI compliance reporting.

- Complete reimbursement of emergency treatment, hospitalisation, EpiPen costs and ongoing medical monitoring.

- Rs. 2-5 lakhs for mental trauma, physical suffering, life-threatening experience, and psychological impact of the anaphylactic shock.

- Rs. 1-3 lakhs as a deterrent punishment for gross negligence in mislabeling a life-threatening product, plus litigation costs and 12% annual interest.

- Mandatory exhibits

I showed Ashima a checklist I had developed:

- Original product with misleading labels

- Purchase receipt/bill

- Photographs of misleading labels

- Medical reports showing health impact

- Laboratory test reports (if available)

- FSSAI complaint reference number

- Evidence of economic loss quantification”

Filing process

- FSSAI complaints

“Online process (recommended):

- Visit foscos.fssai.gov.in/consumergrievance/

- Register as a consumer

- Upload the complaint with supporting documents

- Track status through the portal”

“Contact Information:

- FSSAI Helpline: 1800-112-100 (toll-free)

- Consumer Helpline: 1800-11-4000 (toll-free)

- Email: [email protected]”

2. Consumer Commission

“Online Filing (edaakhil.nic.in):

- Register as a consumer

- Upload the complaint and documents

- Pay the court fee online

- Track case status digitally”

As I explained the filing process, Ashima asked, “What about the limitation period?”

“Crucial question,” I replied. “Under section 69 of the Consumer Protection Act, complaints must be filed within 2 years from when the deficiency was detected. For criminal complaints, it is generally within 3 years, but serious offences have no limitation.”

Prevention: A consumer’s checklist

“Before wrapping up,” I told Ashima, “let me give you a checklist that consumers like Mrs. Sharma can use to protect themselves.”

I pulled out a laminated card I had made for client education:

“Before buying any product, check:

Final thoughts

As Ashima gathered her files, the first hints of dawn were visible through my chamber windows. “Remember,” I concluded, “Mrs. Sharma’s case represents something bigger than misleading cookie labels. It is about the fundamental contract between businesses and consumers in modern India. With the Supreme Court’s strong observations in the Patanjali case, especially Justice Kohli’s and Justice Amanullah’s comments about companies endangering public health for profit, we are entering a new era where food labelling violations face serious accountability under both civil and criminal law.”

“The legal landscape is evolving rapidly, and companies can no longer hide behind ‘innocent error’ defences when their violations systematically mislead vulnerable consumers. Your multi-pronged approach, FSSAI complaint, consumer forum, and potential criminal action ensure that Mrs. Sharma’s case could become the precedent that forces clearer labelling across the entire health food industry. In a democracy built on information and choice, every accurately labelled package is a small victory for justice.”

Allow notifications

Allow notifications