Interim bail meaning explained with legal provisions, key judgments, eligibility, and grounds, plus how interim bail differs from anticipatory and regular bail in India.

Table of Contents

What is Interim Bail?

Interim bail is a temporary form of bail that courts grant while your application for regular bail or anticipatory bail is pending. Think of it as a short-term protection that keeps you out of custody during the time it takes for the court to make a final decision on your main bail application.

The concept addresses a practical reality in our criminal justice system. When you file a bail application, the court needs time to examine case documents, hear arguments from both sides, and make an informed decision. This process can take days or even weeks. Interim bail ensures you don’t spend this waiting period in jail, especially when immediate detention would cause irreparable harm to your reputation, health, or livelihood.

In this comprehensive guide, I’ll explain what interim bail means under Indian law, how it differs from other forms of bail, the legal provisions that govern it, and the practical steps you need to take to apply for it. Whether you’re an accused person seeking immediate relief, a lawyer preparing an application, or a law student studying criminal procedure, this article provides the complete framework you need to understand interim bail in India.

Definition of Interim Bail Under Indian Law

The Supreme Court in Sukhwant Singh vs State of Punjab [2009 (7) SCC 559] provided crucial clarity on interim bail’s nature. The Court held that “in the power to grant bail there is inherent power in the court concerned to grant interim bail to a person pending final disposal of the bail application.” This landmark judgment recognized that interim bail flows from the court’s inherent jurisdiction, not from any specific statutory provision. The Court emphasized that while granting such relief is discretionary, the power certainly exists to protect accused persons from irreparable harm to their reputation during procedural delays.

The Allahabad High Court Full Bench in Amaravati vs. State of U.P. [2005 CRILJ755] held that courts possess the inherent power to grant interim bail pending final disposal of regular bail applications, emphasizing that bail matters must be decided expeditiously as delay in custody can cause irreparable loss to a person’s reputation. This principle was approved and elevated to a nationwide directive by the Supreme Court in Lal Kamlendra Pratap Singh vs State of U.P. & Ors., [(2009) 4 SCC 437] which mandated that “in appropriate cases interim bail should be granted pending disposal of the final bail application” since arrest and detention, even for a short period, can inflict irreparable harm to reputation, especially when allegations appear exaggerated or procedural delays are inevitable.

Together, these judgments form the bedrock of modern interim bail jurisprudence in India, obliging courts to lean in favour of temporary release “without much ado” in suitable cases to protect personal liberty and dignity under Article 21 during the pendency of substantive bail hearings.

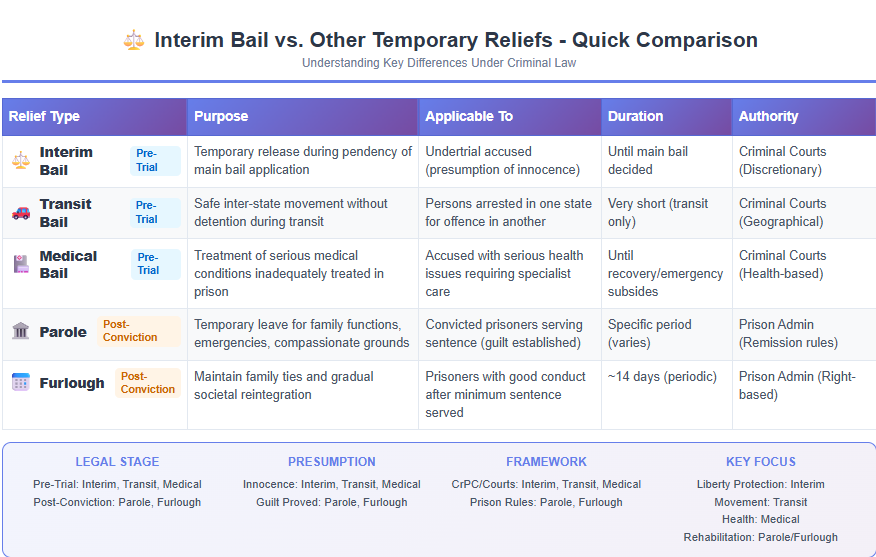

Interim Bail vs. Other Temporary Reliefs Under Criminal Law

The criminal justice system offers various forms of temporary relief, each serving distinct purposes. Understanding how interim bail differs from these other mechanisms helps you choose the right legal remedy for your situation. Let me explain the key differences between interim bail and other temporary measures.

How Does Interim Bail Differ from Transit Bail?

Transit bail is a specialized form of relief you need when you’re arrested in one state for an offence committed in another state. It allows you to travel from the place of arrest to the jurisdiction where the case is registered without being detained during transit. Transit bail is typically granted for a very short period; just enough time for you to reach the appropriate court and apply for regular bail there.

In contrast, interim bail serves a different purpose altogether. While transit bail facilitates your movement between jurisdictions, interim bail provides temporary release during the pendency of your main bail application in the same court. Transit bail is about geographical movement; interim bail is about temporal protection until your substantive bail is decided. You might need transit bail to reach the Sessions Court in another state, and then apply for interim bail there while your regular bail application is being heard.

How Does Interim Bail Differ from Medical Bail?

Medical bail is a specific category of relief granted when you’re suffering from serious medical conditions that cannot be adequately treated in prison facilities. Courts grant medical bail based primarily on health considerations, often requiring you to submit detailed medical reports, specialist opinions, and hospital admission recommendations. The duration of medical bail typically continues until you recover or until the medical emergency subsides.

Interim bail, while it can be sought on medical grounds, is broader in scope and purpose. You can apply for interim bail based on various grounds including reputation protection, procedural delays, family emergencies, or humanitarian considerations; not just health issues. Medical bail focuses exclusively on your health needs and treatment requirements, whereas interim bail addresses the broader concern of preventing unjust detention during bail proceedings. When you seek interim bail on medical grounds, you’re using health as one of several possible justifications for temporary release.

How Does Interim Bail Differ from Parole?

Parole is a form of conditional release granted to convicted prisoners who are already serving their sentence. It allows you to temporarily leave prison for specific purposes like attending family functions, dealing with family emergencies, or other compassionate grounds. Parole applies only after conviction and sentencing, and it’s governed by prison regulations and remission rules rather than criminal procedure codes.

Interim bail operates in an entirely different context; before trial or during trial, not after conviction. You apply for interim bail when you’re an undertrial accused, not a convicted prisoner. While parole is a prison administration matter involving sentence remission authorities, interim bail is a judicial remedy granted by criminal courts. The legal framework, eligibility criteria, and purposes are fundamentally different. Parole assumes your guilt has been established; interim bail operates under the presumption of innocence.

How Does Interim Bail Differ from Furlough?

Furlough is another post-conviction relief available to prisoners who have served a certain minimum period of their sentence with good conduct. It’s essentially a short-term release (typically 14 days) granted periodically to help convicts maintain family ties and gradually reintegrate into society. Furlough is considered a matter of right for eligible prisoners meeting specific criteria related to sentence duration and behavior.

Interim bail, by contrast, is a discretionary relief available to undertrials; people who haven’t been convicted yet. You don’t need to prove good conduct over years of imprisonment; instead, you need to demonstrate grounds for temporary release during bail proceedings. Furlough is part of the prison system’s rehabilitation framework for convicts, while interim bail is part of the criminal justice system’s mechanism to protect the rights of accused persons. The two serve completely different stages of the criminal process and different categories of people.

Difference Between Interim Bail and Anticipatory Bail

Anticipatory bail is a pre-arrest remedy you can seek under Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS when you have reason to believe you might be arrested for a non-bailable offence. It’s a protective shield you apply for before the arrest actually happens, allowing you to avoid custody altogether if the bail is granted. Once granted, anticipatory bail protects you from arrest itself, and if arrested, you’re released immediately on bail.

Interim bail serves a different timing and purpose. You apply for it when a bail application (either regular or anticipatory) is already pending before the court, and you need immediate temporary relief while the court examines the main application. Interim bail doesn’t prevent arrest; it provides temporary release after arrest or during the pendency of anticipatory bail proceedings. Anticipatory bail, once granted, continues until cancelled by the court, while interim bail is strictly time-bound, typically lasting only until the next hearing date or a few weeks at most.

Difference Between Interim Bail and Regular Bail

Regular bail is the main substantive relief you seek after being arrested and taken into custody for a criminal offence. Under Sections 437 and 439 CrPC/Sections 480 and 483 BNSS, you apply for regular bail asking the court to release you from custody on certain conditions while your trial proceeds. Regular bail, once granted, continues throughout the trial until conviction, acquittal, or cancellation by the court.

Interim bail is temporary relief you seek while your regular bail application is being processed and decided. When you file for regular bail, the court may take several days or weeks to hear arguments, examine case documents, and pass orders. During this waiting period, interim bail ensures you don’t remain in custody unnecessarily. Once the court decides your regular bail application; whether granting or rejecting it; the interim bail automatically lapses. Regular bail is the destination; interim bail is the bridge that gets you there safely.

Interim Bail Laws in India

Understanding the legal framework governing interim bail is essential for effectively seeking this relief. Unlike regular bail or anticipatory bail, interim bail doesn’t have a dedicated section in either the Code of Criminal Procedure (CrPC) or the new Bharatiya Nagarik Suraksha Sanhita (BNSS) 2023. Instead, it emerges from the inherent powers of courts and their discretion under various bail provisions. Let me explain the legal foundations that enable courts to grant interim bail.

Relevant Provisions Under BNSS/CrPC

Inherent Powers of Courts to Grant Interim Relief

Courts in India possess inherent powers under Section 482 CrPC/Section 528 BNSS to make orders necessary to prevent abuse of process or to secure the ends of justice. These inherent powers form the primary legal basis for granting interim bail. When the strict letter of law doesn’t provide a specific remedy, courts can invoke their inherent jurisdiction to fill the gap and ensure fairness.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly affirmed that the power to grant interim bail flows naturally from the court’s jurisdiction to hear the main bail application. If a court has the authority to decide on regular bail or anticipatory bail, it inherently possesses the power to grant temporary relief during the pendency of that decision. This ensures that procedural delays don’t result in unjust detention, thereby upholding the constitutional mandate of personal liberty and fair procedure.

Interim Bail Under Sections 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS

Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS governs bail in non-bailable offences by Magistrates. While this section doesn’t explicitly mention interim bail, courts have interpreted it to include the power to grant temporary relief. When you file a bail application under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS, the Magistrate needs time to obtain the case diary from police, hear the prosecution’s objections, and examine the circumstances. During this examination period, the Magistrate can grant interim bail to prevent unnecessary custody.

In Gudikanti Narasimhulu vs. Public Prosecutor, High Court of A.P. (1978 AIR 429), the Supreme Court emphasized that personal liberty is too precious to be lightly dealt with, and bail provisions should be interpreted liberally to advance personal freedom.

Several courts have extended this principle while dealing with interim bail under Section 437 CrPC (now Section 480 BNSS). The Court held that when bail applications are pending, courts should exercise their discretion judiciously to prevent prolonged detention, especially when immediate custody serves no legitimate purpose. This judgment provides the interpretive foundation for Magistrates granting interim bail under their Section 437 CrPC/ Section 480 BNSS jurisdiction.

Interim Bail Under Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS

Section 438 CrPC/Section 482 BNSS specifically deals with anticipatory bail or pre-arrest bail. Under the CrPC regime, the provision explicitly contemplated “interim orders” of protection (including the mandatory 7-day notice to the Public Prosecutor before final orders) to prevent arrest while the main anticipatory bail application was being heard.

The revamped Section 482 BNSS has deliberately omitted any explicit reference to “interim orders” or the statutory notice procedure that existed under the CrPC. The new provision essentially reverts to the pre-2005 format of anticipatory bail, without statutory recognition of interim anticipatory bail. However, courts across India (including the Supreme Court, Bombay High Court, Jammu & Kashmir High Court, and others) continue to routinely grant interim pre-arrest protection in deserving cases while the main anticipatory bail application is pending. This power is now exercised as part of the court’s general discretionary jurisdiction under Section 482 BNSS itself or, more explicitly, under the inherent powers preserved in Section 528 BNSS.

This ensures that the accused is not arrested merely because the court needs time to hear the Public Prosecutor or examine records, thereby upholding Article 21 rights without statutory gaps derailing established practice.

Interim Bail Under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS

Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS grants special powers to the High Court and Court of Sessions regarding bail. These superior courts can grant bail or direct the release of any person in custody, regardless of whether they’re accused of bailable or non-bailable offences. The wide discretion given to these courts under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) includes the power to grant interim bail.

When you approach the Sessions Court or High Court under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) , these courts often need to call for case records from lower courts, examine charge sheets, and hear detailed arguments. This process can take considerable time. The expansive language of Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) empowering these courts to “direct that any person accused of any offence be released on bail” encompasses interim orders for temporary release. Courts have held that the power to grant substantive relief necessarily includes the lesser power to grant interim relief during the decision-making process.

Interim Bail Under the Constitution of India

Article 21: Right to Life and Personal Liberty

Article 21 of the Constitution guarantees that no person shall be deprived of life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law. This fundamental right forms the constitutional bedrock of all bail jurisprudence in India, including interim bail. Your right to personal liberty doesn’t vanish merely because you’re accused of a crime; it can only be restricted through fair, just, and reasonable procedures.

The expanded interpretation of Article 21 in Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978) 1 SCC 248); holding that any procedure depriving a person of life or personal liberty must be just, fair, and reasonable; forms the constitutional foundation of modern bail jurisprudence. Prolonged or arbitrary detention, even during procedural delays in deciding bail applications, violates this mandate when no compelling necessity exists. Building on this principle, courts have repeatedly held that interim bail is often constitutionally required to prevent procedural delays from defeating the very right to liberty that Article 21 protects.

Presumption of Innocence Until Proven Guilty

One of the foundational principles of criminal law is that you’re presumed innocent until the prosecution proves your guilt beyond reasonable doubt. This presumption isn’t just a trial principle; it applies from the moment you’re accused and extends throughout the proceedings. Bail decisions, including interim bail, must respect this presumption and not treat you as a convict before conviction.

In State of Rajasthan vs. Balchand alias Baliay (1977 AIR 2447), the Hon’ble Supreme Court articulated the famous principle that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception.” The Court emphasized that detention during trial should be the exception, not the norm, because you’re presumed innocent. This judgment fundamentally shaped interim bail jurisprudence. When courts consider interim bail applications, they must remember that you stand before them as an innocent person according to law. Keeping you in custody during bail proceedings, unless absolutely necessary for legitimate reasons, contradicts the presumption of innocence. Interim bail gives practical effect to this constitutional presumption during procedural delays.

Bail is Rule, Jail is Exception

The principle that “bail is rule, jail is exception” has become a guiding maxim in Indian criminal jurisprudence. It means that granting bail should be the normal course, and detention should require special justification. This principle applies with even greater force to interim bail because you’re seeking temporary relief during proceedings, not permanent release.

In Sanjay Chandra vs. Central Bureau of Investigation [(2012) 1 SCC 40] also known as 2G Scam Case, the Supreme Court reiterated this principle forcefully, emphasizing that bail rules should not be so stringent that they make bail practically unattainable. The Hon’ble Supreme Court held that the object of bail is to secure attendance at trial, not to punish the accused before conviction. This judgment directly supports interim bail principles. If permanent bail should be the rule, then temporary interim bail during pendency becomes even more compelling. When courts have the power to grant full bail, denying interim relief during decision-making periods would be inconsistent with this fundamental principle. The judgment requires courts to apply this liberal approach to all forms of bail, including interim relief.

Which Court Should You Approach for Interim Bail?

Determining the appropriate court for your interim bail application is crucial for success. The hierarchy and jurisdiction of courts in India means you must file your application in the right forum to avoid rejection on technical grounds. Let me explain which courts have the power to grant interim bail and how you should decide where to file your application.

Sessions Court Jurisdiction for Interim Bail

The Sessions Court has extensive powers to grant bail under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS for any offence, whether bailable or non-bailable, triable by any court within its sessions division. When you’re accused of serious offences triable by Sessions Court (like murder, rape, or offences punishable with imprisonment exceeding seven years), the Sessions Court becomes your natural forum for seeking both regular bail and interim bail.

Sessions Courts also function as appellate courts for bail matters decided by Magistrates. If a Magistrate rejects your bail application, you can approach the Sessions Court, and during the hearing of this appeal, you can simultaneously seek interim bail. The Sessions Court’s special powers under Section 439 CrPC (Section 483 BNSS) include the authority to grant interim protection while examining the merits of your main bail application. Given their wider jurisdiction and experience with serious criminal matters, Sessions Courts are often more receptive to granting interim bail in complex cases requiring detailed examination.

High Court Powers to Grant Interim Relief

High Courts possess constitutional powers under Article 226 (writ jurisdiction) and statutory powers under Section 439 CrPC/Section 483 BNSS to grant bail in any criminal case. As the highest court in the state, the High Court can grant interim bail either when a bail application is directly filed before it or when you approach it in revision against a lower court’s order denying bail.

The High Court’s broad discretion allows it to grant interim bail even in cases where lower courts have been conservative or have denied relief. When you face serious charges, when lower courts have rejected your bail multiple times, or when your case involves complex legal questions, approaching the High Court for interim bail can be strategically advantageous. High Courts also tend to grant longer interim bail periods compared to Magistrates or Sessions Courts, giving you more time to prepare for the final bail hearing and reducing the frequency of seeking extensions.

Supreme Court’s Role in Interim Bail Matters

The Supreme Court is the apex judicial authority in India and has the power to grant interim bail under Article 32 (fundamental rights jurisdiction) and Article 136 (special leave petition). When you approach the Supreme Court, it’s typically in extraordinary circumstances; either because lower courts and High Courts have denied relief, or because your case involves questions of national importance or constitutional significance.

In Arnesh Kumar vs. State of Bihar (AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 2756), the Supreme Court laid down comprehensive guidelines to prevent mechanical and arbitrary arrest in the matrimonial offence cases under Section 498A IPC/Section 85 BNS and other cases punishable with imprisonment of seven years or less. The judgment emphasised that arrest must be the exception and that Magistrates must scrutinise the necessity of custody. These guidelines are frequently invoked while granting accused persons on interim bail across the country.

When the Supreme Court does grant interim bail in extraordinary cases, the order carries immense weight and often influences the final outcome of the regular bail application. The duration and conditions vary depending on the facts; the Court may grant relatively longer periods in appropriate cases, but it also imposes stringent conditions tailored to the gravity and sensitivity of the matter.

Can Magistrate Court Grant Interim Bail?

Yes, Magistrate Courts can grant interim bail, though their jurisdiction is more limited compared to Sessions Courts and High Courts. When you’re accused of offences triable by a Magistrate and you file a regular bail application under Section 437 CrPC/Section 480 BNSS), the Magistrate has the authority to grant interim bail.

How to Decide Before Which Court to File Interim Bail Application?

The decision on which court to approach depends primarily on where your main bail application is filed or pending. If you’ve already filed a regular bail application before a Magistrate, you should seek interim bail from the same Magistrate. If your case is triable by Sessions Court or if you’re approaching Sessions Court in revision against a Magistrate’s order, file your interim bail application there.

Consider the seriousness of your offence, the stage of proceedings, and past rejections when choosing the forum. For serious offences with significant evidence against you, directly approaching the Sessions Court or High Court might be strategically better as these courts have wider discretion and experience with complex cases. If lower courts have already rejected your bail once or twice, approaching the High Court for interim bail while filing a revision application can be more effective than repeatedly seeking relief from the same lower court that denied you earlier.

Who Can Apply for Interim Bail?

Understanding eligibility for interim bail helps you determine whether this remedy is available in your situation. While interim bail is broadly accessible, certain conditions and timing considerations affect who can successfully apply for it. Let me explain the eligibility criteria and practical considerations for seeking interim bail.

Eligibility Criteria for Interim Bail

Any person who has filed or is about to file a bail application; whether regular bail or anticipatory bail; can seek interim bail. You don’t need to meet different criteria than those required for the main bail application. If you’re eligible to apply for regular bail (because you’ve been arrested) or anticipatory bail (because you apprehend arrest), you’re automatically eligible to seek interim relief during the pendency of those proceedings. The key requirement is that you must have a pending bail application or be filing one simultaneously with the interim bail request.

Your eligibility also depends on demonstrating urgent grounds that justify immediate temporary relief. Courts won’t grant interim bail simply because you want it; you need to show compelling reasons why you shouldn’t remain in custody during the time the court needs to decide your main application. Medical emergencies, reputation concerns, family crises, or procedural delays that could result in prolonged detention before hearing are typical grounds that establish eligibility for interim bail.

When Should You File an Interim Bail Application?

The ideal time to file an interim bail application is immediately after filing your main bail application (regular or anticipatory bail) or when you realise that the hearing on your main application will be delayed significantly. If you’ve been arrested and the Magistrate has adjourned your bail hearing by two weeks to examine the case diary, that’s the moment to apply for interim bail. Similarly, if you’ve filed anticipatory bail and the court has issued notice to the prosecution with the next hearing scheduled after a month, seeking interim protection during this period makes absolute sense.

Who Cannot Apply for Interim Bail?

You cannot apply for interim bail if you haven’t filed any bail application at all or if you’re not eligible for bail under the applicable law. If your offence falls under special statutes that impose strict bail restrictions like certain provisions of the the Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act 1985 (NDPS), Unlawful Activities (Prevention Act) 1967 (UAPA), or Prevention of Money Laundering Act 2002 (PMLA); and you don’t meet the threshold conditions for bail itself, seeking interim bail becomes futile. Additionally, if you’ve previously violated bail conditions, absconded, or have a history of not appearing in court, your interim bail application will likely be rejected regardless of other grounds.

Grounds for Granting Interim Bail in India

Courts grant interim bail based on specific grounds that demonstrate your need for immediate temporary relief. Understanding these grounds helps you frame effective applications that resonate with judicial priorities. Let me explain the various grounds courts recognise for granting interim bail.

What Grounds Can You Use to Apply for Interim Bail?

Medical Emergency and Health-Related Grounds

Serious medical conditions requiring urgent treatment outside prison facilities constitute one of the strongest grounds for interim bail. If you’re suffering from terminal illness, require surgery, need specialized medical care unavailable in prison hospitals, or face health deterioration that cannot be addressed in custody, courts readily grant interim bail. You must support your application with detailed medical reports, specialist opinions, and hospital recommendations demonstrating the urgency and necessity of treatment outside custody.

Protection of Reputation and Professional Standing

When immediate arrest and detention would cause irreparable harm to your professional reputation, social standing, or career prospects, courts consider this a valid ground for interim bail. Courts recognize that false or exaggerated allegations can be weaponised to damage reputations, and interim bail serves as a safeguard until the merits are properly examined.

Procedural Delays in Regular Bail Hearing

When the court needs extended time to obtain case records, hear detailed arguments, or examine voluminous documents before deciding your main bail application, this procedural delay itself becomes a ground for interim bail. If the prosecution seeks multiple adjournments, if the case diary takes weeks to arrive from the investigating agency, or if the complexity of the case requires lengthy hearings spanning multiple dates, you shouldn’t suffer custody throughout this period. Courts grant interim bail to ensure procedural timelines don’t become instruments of punishment before trial.

When Do Courts Grant Interim Bail on Humanitarian Grounds?

Family Emergencies and Compassionate Circumstances

Courts grant interim bail when you face genuine family emergencies like the death of close relatives, serious illness of immediate family members, or urgent family responsibilities that require your presence. For instance, the Supreme Court vide Suo Motu WP(C) No. 01/2020 and various High Courts granted interim bail on humanitarian and compassionate ground to several undertrials during 2020–2021 for performing last rites of parents/spouses who died of COVID-19, recognizing that denying such relief would be inhumane and violative of Article 21 dignity.

Interim Bail for Women, Elderly, and Vulnerable Accused

The Supreme Court has repeatedly emphasized that special consideration should be given to women, elderly persons above 65 years, and vulnerable accused persons when deciding bail applications. In Natasha Narwal vs. State of Delhi NCT (CRL.A. 82/2021), the Hon’ble Delhi High Court granted three-week interim bail on humanitarian grounds when the accused’s father died from COVID-19, recognizing that women accused in custody face additional vulnerabilities. Courts acknowledge that prolonged detention of elderly or vulnerable accused pending bail hearings can cause disproportionate hardship and health deterioration.

Primary Breadwinner and Dependent Family Considerations

When you’re the sole breadwinner of your family and your continued detention would push your dependents into financial crisis, courts may grant interim bail on humanitarian grounds. The Hon’ble Rajasthan High Court in Bhawani Pratap Singh v. State of Rajasthan, 2025 SCC OnLine Raj 2885, granted 60 days of temporary bail to an NDPS accused on humanitarian grounds, recognizing that while his wife’s pregnancy and lack of family assistance were insufficient for regular bail, they constituted reasonable grounds to permit temporary release for discharging familial obligations. The Court adopted a balanced approach that upheld the custodial process while accommodating legitimate personal concerns, emphasizing that criminal justice is not merely punitive but reformative and humane.

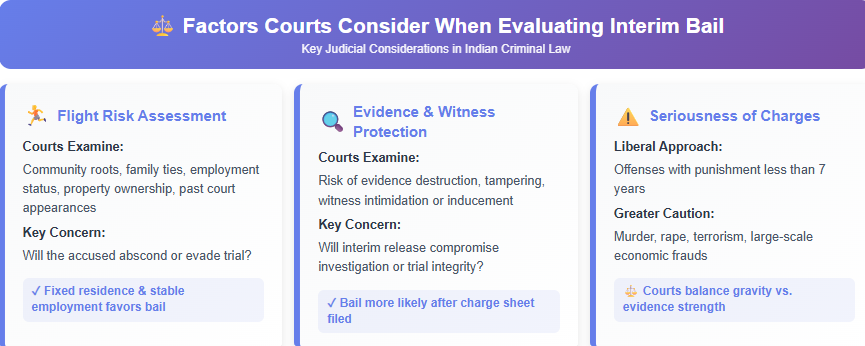

What Factors Do Courts Consider When Evaluating Interim Bail Requests?

When you file an interim bail application, courts don’t grant relief automatically. They carefully evaluate several factors to determine whether temporary release is justified or whether you should remain in custody until the main bail hearing concludes. Understanding these evaluation factors helps you address judicial concerns proactively in your application.

Possibility of the Accused Absconding or Evading Trial

The primary concern for any court granting bail is whether you’ll appear for trial or abscond. Courts examine your roots in the community, family ties, employment status, property ownership, and past conduct to assess flight risk. If you have permanent residence, stable employment, strong family connections, and have appeared regularly in other cases, courts are more comfortable granting interim bail. Conversely, if you lack fixed residence, have a history of avoiding court appearances, or possess resources that could facilitate absconding (like foreign connections or liquid assets), courts become extremely cautious about interim relief.

Potential for Destruction of Evidence or Influencing Witnesses

Courts carefully assess whether granting interim bail could compromise the investigation or trial. If the investigation is still ongoing and you have access to evidence that could be destroyed, tampered with, or concealed, courts may deny interim bail until the investigation concludes. Similarly, if key witnesses are vulnerable to pressure, threats, or inducement from the accused or his/her associates, courts protect witness integrity by keeping you in custody. However, when the investigation is complete, the charge sheet has been filed, and evidence has been secured, this concern diminishes significantly, making interim bail more likely.

Seriousness and Nature of the Criminal Charges

The gravity of the offence charged against you plays a crucial role in interim bail decisions. For offences or cases where the maximum punishment is less than seven years, courts adopt a liberal approach to interim bail. However, for serious offences like murder, rape, terrorism, or large-scale economic frauds, courts exercise greater caution. Even in serious cases, interim bail can be granted if you demonstrate compelling grounds like terminal illness or if the charges appear prima facie weak or exaggerated. Courts balance the seriousness of allegations against the strength of evidence and your individual circumstances when evaluating interim bail in grave offence cases.

Conditions Imposed by Courts When Granting Interim Bail

When courts grant interim bail, they don’t simply release you without safeguards. They impose specific conditions designed to ensure you appear for hearings, don’t interfere with the investigation or trial, and don’t misuse the temporary liberty granted. Let me explain the typical conditions you’ll need to comply with during interim bail.

What Conditions Does the Court Impose During Interim Bail?

Personal Appearance Requirements in Court

You must appear personally before the court on all dates specified in the interim bail order and on the final hearing date of your main bail application. Courts typically mandate that you remain present throughout hearings unless specifically exempted. Failure to appear even once can result in immediate cancellation of your interim bail and issuance of a non-bailable warrant. Some courts require you to mark attendance before the court clerk or reader on each hearing date, creating a documented record of your compliance with appearance conditions.

Police Station Reporting

Courts often require you to report to the investigating police station or the local police station in your area at regular intervals; daily, weekly, or biweekly depending on the case’s nature and seriousness. This reporting requirement serves multiple purposes: it ensures you’re available within the jurisdiction, allows police to monitor your movements, and provides assurance that you haven’t absconded. You must maintain a register or obtain acknowledgement slips from the police station as proof of compliance, which may be verified by the court during subsequent hearings.

Surety and Bond Amount Requirements

Courts typically require you to furnish a personal bond and one or two sureties as security for your temporary release. The bond amount varies based on the offence’s seriousness, your financial status, and the court’s assessment of flight risk. For minor offences, bonds might range from ₹10,000 to ₹50,000, while serious offences can attract bond amounts of ₹1 lakh to ₹5 lakhs or more. Sureties must be solvent persons who own property or have stable income and who undertake to produce you before the court when required, failing which their property can be attached or they become liable for the bond amount.

Passport Surrender

In cases involving serious offences or when you have resources to flee the country, courts mandate surrender of your passport to the court or investigating agency. This condition prevents international travel and eliminates the risk of you evading trial by leaving India. Even when passport surrender isn’t explicitly ordered, courts routinely include conditions prohibiting you from leaving the country without prior court permission, effectively achieving the same purpose. If your profession requires international travel, you must specifically apply for temporary return of passport with full itinerary and justification, which courts rarely grant during interim bail periods.

Prior Permission Requirements for Inter-State Travel

Courts restrict your movement to a specific geographical area: usually the district or state where the case is pending. If you need to travel outside this jurisdiction for any reason (medical treatment, business emergency, family function), you must obtain prior written permission from the court. This requires filing a formal application explaining the necessity, duration, and destination of travel, and waiting for court orders before traveling. Traveling without permission, even within India, constitutes violation of bail conditions and can lead to immediate cancellation.

No Contact with Witnesses or Complainants

Courts strictly prohibit any direct or indirect contact with prosecution witnesses, complainants, or their family members during interim bail. This condition protects witness integrity and prevents any attempt at intimidation, inducement, or pressure that could compromise their testimony. You cannot meet them personally, call them, send messages through intermediaries, or make any contact whatsoever. Even accidental encounters must be avoided, as complainants can allege harassment, leading to bail cancellation. Courts take violations of this condition extremely seriously as it directly undermines the trial’s fairness.

Cooperation with Investigation Requirements

You must make yourself available to the investigating agency for interrogation whenever summoned and must cooperate fully with the investigation. This includes answering questions, participating in identification parades, providing voice samples, or submitting to medical examinations if required. Courts expect you to facilitate investigation rather than obstruct it, as interim bail is granted in good faith that you’ll help uncover the truth. However, cooperation doesn’t mean you surrender your fundamental rights; you retain the right to legal counsel during interrogation and the right against self-incrimination.

Can Interim Bail Be Cancelled or Revoked?

Interim bail isn’t an absolute right that continues indefinitely. Courts retain the power to cancel or revoke interim bail if circumstances change or if you violate the conditions imposed. Understanding cancellation grounds and consequences helps you maintain compliance and avoid jeopardizing your temporary liberty.

Grounds for Cancellation of Interim Bail

Courts can cancel your interim bail if you violate any imposed conditions (failing to appear in court, not reporting to police station, contacting witnesses, attempting to tamper with evidence, or leaving the jurisdiction without permission). Even minor violations can lead to cancellation if they demonstrate lack of good faith or disrespect for court orders.

Additionally, if new evidence emerges showing you committed the offence or if you commit fresh offences while on interim bail, courts cancel the relief immediately. The prosecution can also move an application highlighting that you’re misusing the liberty granted, and upon satisfying the court about such misuse, interim bail stands cancelled.

Consequences of Violating Interim Bail Conditions

Immediate Cancellation and Arrest

The moment the court finds you’ve violated interim bail conditions, it cancels the bail order and issues a non-bailable warrant for your immediate arrest. You lose the interim protection instantly and must surrender to custody. The cancelled interim bail cannot be revived; you must start fresh by filing a new application explaining the violation and seeking reconsideration.

Courts treat condition violations seriously because they reflect poorly on your trustworthiness and respect for the judicial process. Even if your violation seems minor to you (like missing one police station reporting date due to illness), courts view it as a breach of undertaking given to secure temporary liberty. The burden shifts to you to explain and justify the violation convincingly, failing which you remain in custody until the main bail hearing concludes.

Impact on Regular Bail Application

Violating interim bail conditions severely prejudices your main bail application. When the court hears your regular bail or anticipatory bail, the prosecution will highlight that you misused interim liberty, failed to comply with simple conditions, and demonstrated that you cannot be trusted with bail. This significantly weakens your case for regular or anticipatory bail. Judges become skeptical about granting you longer-term relief when you’ve already proven unreliable during the short interim period. Your violation becomes strong evidence supporting the prosecution’s argument that you’ll abscond, tamper with evidence, or otherwise misuse bail if granted on a regular basis.

Contempt of Court Proceedings

Willful and deliberate violation of interim bail conditions can amount to contempt of court under the Contempt of Courts Act, 1971. If you deliberately disobey court orders (like intentionally failing to appear despite being able to, or deliberately contacting witnesses after being explicitly prohibited), the court can initiate contempt proceedings against you. Contempt of court carries punishment of up to six months imprisonment and fine. While courts don’t routinely invoke contempt powers for every bail violation, egregious or repeated violations demonstrating intentional defiance of court orders can attract contempt action, compounding your legal troubles significantly beyond just bail cancellation.

Can You Apply for Interim Bail Again If It Has Been Cancelled?

Yes, you can apply for interim bail again even after cancellation, but success becomes significantly more difficult. You must satisfactorily explain the circumstances that led to the earlier violation and convince the court that those circumstances won’t recur. If the violation was genuinely inadvertent (like missing a court date due to sudden hospitalization with proper documentation), courts may consider fresh interim bail. However, if you deliberately violated conditions or showed callous disregard for court orders, getting interim bail again becomes nearly impossible.

When filing a fresh application after cancellation, you need exceptionally strong grounds; like new medical emergencies, changed family circumstances, or other compelling humanitarian reasons that weren’t present earlier. Courts exercise heightened scrutiny and may impose stricter conditions if they grant relief at all. In Kalyan Chandra Sarkar v. Rajesh Ranjan [(2005) 2 SCC 42], the Supreme Court held that successive bail applications are permissible if based on new grounds, changed circumstances, or fresh material not considered earlier. In a subsequent bail application, the accused can highlight aspects overlooked in prior orders. However, courts must guard against abuse of process and are not obliged to entertain repetitive applications raising the same old grounds.

Landmark Judgments on Interim Bail

The evolution of interim bail jurisprudence in India owes much to landmark Supreme Court and High Court judgments that have clarified its scope, conditions, and legal foundations. These precedents guide courts daily in evaluating interim bail applications and establishing the balance between personal liberty and public interest. Let us discuss the most significant judgments that have shaped interim bail jurisprudence.

Lal Kamlendra Pratap Singh vs. State of UP [(2009) 4 SCC 437]

This Supreme Court judgment is the cornerstone of interim bail jurisprudence in India, establishing the inherent power of courts to grant such relief and recognising reputation protection as a valid ground.

Inherent Power of Courts to Grant Interim Bail

The Supreme Court explicitly held that “in the power to grant bail there is inherent power in the court concerned to grant interim bail to a person pending final disposal of the bail application.” This statement resolved any ambiguity about courts’ authority to grant interim bail even without specific statutory provisions. The Court reasoned that when bail applications are filed, courts need time to examine case diaries, hear arguments, and make informed decisions. During this examination period, keeping the accused in custody could cause irreparable harm.

The judgment established that the inherent power to grant interim bail flows naturally from the jurisdiction to hear the main bail application. If a court can grant permanent bail after full hearing, it necessarily possesses the lesser power to grant temporary relief during the hearing process. This power isn’t arbitrary or unlimited; courts must exercise it judiciously based on the circumstances of each case, the grounds presented, and the balance between personal liberty and public interest.

Protection of Reputation as Valid Ground

Relying on a landmark judgment passed by the Hon’ble Supreme Court in Joginder Kumar vs. State of U.P. [1994 AIR 1349], the Court recognized that a person’s reputation is an invaluable asset and forms part of their fundamental rights under Article 21 of the Constitution. When someone files for bail, the court typically schedules hearings after several days to obtain case records from police. During this waiting period, the applicant must remain in custody. Even if bail is subsequently granted, the person’s reputation in society may already be irreparably damaged by the mere fact of custody, regardless of actual guilt or innocence.

When allegations appear exaggerated or when keeping the accused in custody for procedural periods serves no legitimate purpose, courts should grant interim bail to prevent such irreparable harm. Thus, in view of the aforesaid circumstance, the Hon’ble Supreme Court directed that interim bail should be granted pending final disposal of bail applications when immediate custody would cause disproportionate damage to reputation compared to any public interest served by detention.

Arnesh Kumar v. State of Bihar (AIR 2014 SUPREME COURT 2756)

This landmark judgment revolutionized arrest practices in India, particularly in matrimonial offence cases, and significantly impacted interim bail jurisprudence by establishing guidelines to prevent arrest abuse.

Guidelines to Prevent Misuse of Arrest Powers

The Supreme Court issued nine comprehensive guidelines to prevent mechanical and arbitrary arrests under Section 498A IPC/Section 85 BNS (dowry harassment) and similar provisions. The Court directed that police officers must not automatically arrest when complaints are filed; instead, they must satisfy themselves that arrest is necessary under Section 41 CrPC (now Section 35 BNSS), which requires reasonable grounds to believe arrest is necessary to prevent the accused from committing further offences, to ensure presence for investigation, to prevent evidence destruction, or to prevent witness intimidation.

The Court mandated that police must complete a checklist documenting reasons for arrest in each case, and this checklist must be produced before the Magistrate when seeking remand. Magistrates were directed to carefully scrutinize arrest justifications before authorizing further detention. If police arrest without satisfying Section 41 CrPC (now Section 35 BNSS) conditions, they can be held liable for contempt of court. These guidelines fundamentally changed arrest dynamics by making arrest the exception rather than the rule, even in non-bailable offences.

The judgment’s impact on interim bail is profound. When courts evaluate interim bail applications, particularly in matrimonial cases, they now examine whether the original arrest itself was justified under Section 41 CrPC (Section 35 BNSS) criteria. If arrest appears mechanical or unjustified, courts are more inclined to grant interim bail quickly, recognising that the accused shouldn’t suffer custody for arrests that violated Supreme Court guidelines from the outset.

Interim Bail in Section 498A IPC/Section 85 BNS

The Court specifically addressed how its guidelines affect bail considerations in Section 498A IPC (now Section 85 BNS) cases. It recognized that matrimonial disputes are often civil in nature but get criminalized through allegations of cruelty and dowry harassment. Many such complaints are filed with the intent to pressure the accused into favorable settlements rather than to genuinely prosecute crime. When such allegations lead to arrest, interim bail becomes crucial to prevent misuse of the criminal process.

Following Arnesh Kumar, courts have adopted a liberal approach to interim bail in matrimonial cases, particularly when allegations appear exaggerated, when the complainant has filed multiple cross-cases indicating a property or custody dispute rather than genuine criminal victimization, or when the accused hasn’t been given adequate notice before arrest. The judgment established that interim bail should be readily available in such cases to prevent the criminal justice system from being weaponised in personal disputes, while ensuring that genuine victims of domestic violence aren’t denied justice.

Recent High-Profile Interim Bail Cases

Arnab Manoranjan Goswami v. State of Maharashtra & Ors. [AIR 2021 SUPREME COURT 1]

In this high-profile case, the Supreme Court granted interim bail to Republic TV Editor-in-Chief Arnab Goswami in a 2018 abetment to suicide case (under Sections 306 r/w 34 IPC) involving the death of interior designer Anvay Naik and his mother. Goswami was arrested on 4 November 2020; the Bombay High Court denied interim relief on 9 November 2020 while reserving judgment on his quashing petition.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court set aside the High Court’s refusal and directed Goswami’s immediate release on interim bail pending disposal of his quashing petition, on a personal bond of ₹50,000. The Court imposed conditions that he must cooperate fully with the investigation and refrain from tampering with evidence or influencing witnesses. The Court balanced multiple considerations: the fundamental right to personal liberty under Article 21, the presumption of innocence, the need for courts [including High Courts under Article 226/Section 482 CrPC (now Section 528 BNSS)] to grant interim protection when prima facie grounds for quashing exist, and the danger of state machinery being used to stifle free speech and silence journalists.

This case demonstrates that interim bail must be readily granted even in non-bailable offences when deprivation of liberty appears disproportionate or motivated, particularly where allegations seem prima facie unsustainable or vindictive. The Hon’ble Supreme Court emphasised that “bail is the rule and jail is the exception”, that personal liberty is a precious constitutional value, and that High Courts must not relegate accused persons to lengthy statutory remedies when immediate interim relief is warranted to prevent irreparable harm. The interim bail; crafted to protect liberty during pendency of the quashing proceedings without prejudicing the investigation, showed how superior courts can intervene swiftly to uphold Article 21 rights while maintaining judicial control through appropriate conditions.

Arvind Kejriwal v. Directorate of Enforcement (2024) [Criminal Appeal No. 2493 of 2024]

In this high-profile case, the Supreme Court granted interim bail to the sitting Chief Minister of Delhi, Arvind Kejriwal, in a money laundering case investigated by the Enforcement Directorate under the PMLA. The accused was arrested in March 2024 and held in custody for several weeks. The Supreme Court granted him interim bail specifically for a limited period covering the Lok Sabha elections campaign, allowing him to participate in democratic processes.

The Hon’ble Supreme Court’s order imposed strict conditions: Kejriwal could not visit the Delhi Secretariat or his Chief Minister’s office, could not sign official files unless absolutely necessary with Lieutenant Governor’s approval, and had to surrender after the interim bail period expired. The Court balanced multiple considerations: the seriousness of PMLA charges (which have stringent bail restrictions), the presumption of innocence, the accused’s constitutional position as an elected Chief Minister, the importance of free and fair elections requiring his participation as a major political leader, and public interest in allowing democratic processes to function.

This case demonstrates that interim bail can be granted even in serious economic offences under special statutes, but with stringent conditions tailored to the specific circumstances. The Court emphasised that while democratic principles and election participation are important, they don’t override the need to ensure the accused doesn’t misuse interim liberty or interfere with investigation. The limited nature of the interim bail; explicitly tied to the election period rather than indefinite; showed how courts can craft narrow interim relief serving specific compelling purposes while maintaining overall judicial custody and control over serious offence cases.

Conclusion

Interim bail serves as a vital protective mechanism in India’s criminal justice system, ensuring that procedural delays don’t translate into unjust detention for accused persons awaiting final bail decisions. Throughout this guide, I’ve explained how interim bail emerges from courts’ inherent powers to protect your fundamental right to liberty under Article 21 of the Constitution, how it differs from other forms of bail and temporary relief, and the legal framework under CrPC and BNSS 2023 that enables courts to grant such relief. The landmark judgments I’ve discussed: from Lal Kamlendra Pratap Singh’s recognition of inherent judicial power to Arnesh Kumar’s guidelines preventing arrest abuse, and recent high-profile cases; demonstrate the evolving jurisprudence that increasingly favors liberty while balancing legitimate state interests.

If you’re facing criminal charges or anticipating arrest, understanding interim bail empowers you to protect your rights effectively. Remember that interim bail isn’t automatic; you must demonstrate compelling grounds like medical emergencies, reputation protection, humanitarian circumstances, or procedural delays that justify temporary release during bail proceedings. Equally important is compliance with all conditions imposed by courts: appearance requirements, police station reporting, travel restrictions, and prohibitions on witness contact because even minor violations can result in immediate cancellation and significantly prejudice your main bail application. Whether you approach a Magistrate Court, Sessions Court, High Court, or Supreme Court depends on your case’s nature, the offence’s seriousness, and where your main bail application is pending, but the underlying principle remains constant: bail is the rule, jail is the exception, and interim bail gives practical effect to this constitutional mandate during the critical period when courts examine your case to make final bail decisions.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the meaning of interim bail in simple terms?

Interim bail is temporary release granted by court while your regular or anticipatory bail application is pending, protecting you from custody during procedural delays in bail hearing.

What is the duration of interim bail?

Interim bail typically lasts until the next bail hearing date, though duration varies based on case complexity, court level, and specific circumstances requiring temporary relief.

Can interim bail be extended if needed?

Yes, interim bail can be extended by filing extension application before expiry, citing continued procedural delays, pending case diary examination, or other valid grounds for extended temporary relief.

What is the difference between interim bail and anticipatory bail?

Anticipatory bail is pre-arrest protection; interim bail is temporary relief during pendency of any bail application, granted after arrest or during anticipatory bail proceedings.

Is interim bail available for all types of offences?

Interim bail is available for most offences, but courts exercise greater caution in serious crimes, NDPS cases, POCSO offences, and cases with stringent statutory bail restrictions.

What happens when the interim bail period expires?

When interim bail expires without extension, you must surrender to custody; police can arrest you without warrant, and you remain in custody until regular bail is decided.

Can you get interim bail in NDPS Act cases?

Yes, but interim bail in NDPS cases is difficult due to Section 37 restrictions; medical emergencies or terminal illness are primary grounds courts consider in such cases.

What documents are required for interim bail application?

Required documents include inter alia bail application, supporting affidavits, medical certificates (if health ground), custody certificate, identity/address proof of the applicant and the surety, FIR copy and relevant case papers.

Which court grants interim bail?

Any court with jurisdiction to hear your main bail application: Magistrate Court, Sessions Court, High Court, or Supreme Court, can grant interim bail during pendency of proceedings.

Can interim bail be cancelled by the court?

Yes, courts cancel interim bail immediately if you violate any imposed conditions, fail to appear in court, tamper with evidence, contact witnesses, or commit fresh offences.

What conditions does the court impose during interim bail?

Standard conditions include regular court appearance, police station reporting, surety/bond furnishing, passport surrender, travel restrictions, no witness contact, and prohibition on leaving India without permission.

How is interim bail different from regular bail?

Regular bail is permanent release throughout trial after full hearing; interim bail is temporary relief granted during pendency of regular bail application hearing.

Can you travel while on interim bail?

Yes, limited travel is allowed on interim bail, but movement is strictly regulated by court-imposed conditions. Local travel within the permitted area (usually the state/district) is generally free, while inter-state travel requires prior written permission from the court via a formal application stating the reason, duration and itinerary.

International travel is almost always prohibited, with passport surrender and an explicit “shall not leave India” condition being standard.

What are the grounds for granting interim bail in India?

Valid grounds include medical emergencies, reputation protection, procedural delays in bail hearing, humanitarian circumstances, family emergencies, elderly/vulnerable accused status, and primary breadwinner considerations with dependent family.

Related reading: https: Bail Meaning: //lawsikho.com/blog/bail-meaning/; Bail Application Format: https://lawsikho.com/blog/bail-application-format-pdf/

Allow notifications

Allow notifications