Logical Reasoning UGC NET : Syllabus breakdown and analysis. Venn diagram shortcuts, Indian Logic Pramanas, and preparation strategies.

Table of Contents

Let’s be honest: When you first see terms like “Hetvabhasas” and “Vyapti” in the UGC NET syllabus, your instinct is probably to skip this section entirely. Sanskrit in a reasoning unit? No thanks.

But here’s what most aspirants miss: Logical Reasoning is one of the easiest scoring units in Paper I.

Unlike theory heavy units that require endless memorization, this section rewards understanding and practice. The questions follow predictable patterns. The answers are objective no ambiguity, no “most appropriate” guessing games.

And with no negative marking in UGC NET, you can attempt every question confidently. Once you learn the techniques, you can score around 10 marks from this unit reliably.

The intimidating part? Just the vocabulary. Pratyaksha simply means perception. Anumana means inference. Strip away the Sanskrit, and these concepts are surprisingly intuitive, probably easier than remembering which committee recommended what in the Higher Education unit!

This guide will take you from complete beginner to confident problem solver. We’ll cover Western Logic (Venn diagrams, syllogisms, fallacies), Indian Logic (Pramanas, Hetvabhasas), and practical shortcuts that save precious exam minutes. No philosophy background needed. No prior logic experience required.

By the time you finish reading, you’ll have memorizable frameworks, quick solve techniques, and a clear preparation strategy to turn Logical Reasoning into your strongest scoring area.

Ready to master this high scoring unit? Let’s dive in.

Understanding Unit VI of Paper I Syllabus

How Many Questions Come from Logical Reasoning?

Logical Reasoning, classified as Unit VI in the official UGC NET Paper I syllabus, typically contributes 5 questions in each exam session. With each question carrying 2 marks, this translates to 10 marks, which represents approximately 10 percent of the total Paper I score of 100 marks.

Based on analysis of previous year papers from 2022 to 2025, the number has remained consistent, making it a reliable scoring area for prepared candidates.

Logical Reasoning is High Scoring

Unlike theory heavy units such as Teaching Aptitude or Higher Education System that require extensive memorization, Logical Reasoning rewards understanding and practice. Once you learn the underlying concepts and shortcuts, you can solve questions with certainty rather than guesswork.

The questions follow predictable patterns, and there is no ambiguity in answers since logical validity is objective. This means that a well prepared candidate can aim for 100 percent accuracy in this unit.

How is Logical Reasoning Different from Mathematical Reasoning

Many aspirants confuse Logical Reasoning (Unit VI) with Mathematical Reasoning and Aptitude (Unit V), but they test completely different skills. Mathematical Reasoning focuses on numerical patterns, number series, letter series, coding decoding, percentages, ratios, and basic arithmetic calculations. It tests your quantitative aptitude and calculation speed.

Logical Reasoning, on the other hand, deals with the structure of arguments, validity of conclusions, and forms of reasoning. It includes topics like syllogisms, Venn diagrams, deductive and inductive reasoning, fallacies, and the uniquely Indian contribution of Pramanas (means of knowledge).

While Mathematical Reasoning asks “what is the next number in this series,” Logical Reasoning asks “is this conclusion valid given these premises?” Understanding this distinction will help you allocate your preparation time correctly across both units.

Logical Reasoning Topics in UGC NET

Western Logic Topics (4 Sub Topics)

The Western Logic portion of the syllabus covers four major areas that form the foundation of formal logic as developed in the European philosophical tradition. These include understanding the structure of arguments (argument forms, categorical propositions, mood and figure, formal and informal fallacies, uses of language, connotations and denotations, and the classical square of opposition), evaluating and distinguishing deductive and inductive reasoning, analogies, and Venn diagrams for establishing validity of arguments.

These topics are more familiar to most aspirants because they align with reasoning sections found in other competitive exams like CAT, CLAT, and bank examinations. If you have previously prepared for any aptitude test, you likely have some exposure to Venn diagrams and syllogisms.

However, UGC NET goes deeper into the theoretical foundations, requiring you to understand not just how to solve problems but also why certain conclusions are valid or invalid.

Indian Logic Topics (3 Sub Topics Added in Revised Syllabus)

The revised UGC NET syllabus introduced three topics from Indian philosophical traditions that many aspirants find intimidating at first glance. These are Indian Logic and means of knowledge, the six types of Pramanas (Pratyaksha, Anumana, Upamana, Shabda, Arthapatti, and Anupalabdhi), and the structure and kinds of Anumana including Vyapti (invariable relation) and Hetvabhasas (fallacies of inference).

These topics come from the Nyaya school of Indian philosophy, which developed sophisticated logical systems centuries before similar developments in Western philosophy.

The good news is that despite the unfamiliar Sanskrit terminology, the underlying concepts are logical and can be understood with clear explanations and relatable examples. You do not need a philosophy background; you just need patience and the right approach, which this guide will provide.

Weightage of Logical Reasoning in UGC NET Exam: Analysis Based on Previous Year Papers

This table shows the topic wise distribution based on questions analysed from 2022 to 2025 question papers of UGC NET Exam.

| Exam Session | Venn Diagrams | Syllogisms/Arguments | Indian Logic | Analogies | Deductive/Inductive | Total Questions |

| June 2025 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 0-1 | 0-1 | 4-6 |

| Dec 2024 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1 | 1 | 0-1 | 4-5 |

| June 2024 | 2 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 0-1 | 1 | 5-6 |

| Dec 2023 | 1-2 | 1-2 | 1 | 1 | 0-1 | 4-5 |

| June 2023 | 1-2 | 2 | 1 | 0-1 | 1 | 5-6 |

Note: Question distribution varies slightly across different shifts within the same session. The ranges above reflect this variation.

Which Sub-Topics Appear Most Frequently?

Venn diagram questions are the most consistent performers in UGC NET Logical Reasoning. Almost every exam session includes at least one question asking you to test the validity of a syllogism using Venn diagrams.

These questions are highly predictable in format: you receive two or three premises and must determine whether the conclusion follows necessarily. Mastering Venn diagrams alone can guarantee you 2 to 4 marks in every exam.

Syllogisms and argument structure questions appear with equal regularity, testing your understanding of categorical propositions (All, No, Some, Some not), mood and figure, and validity rules.

Questions may ask you to identify valid syllogistic forms, find the conclusion from given premises, or determine which premise is missing. The square of opposition, a concept that shows relationships between different types of propositions, appears frequently in these questions.

Indian Logic questions have become increasingly common since their addition to the syllabus. Questions typically test your knowledge of the six Pramanas (asking which Pramana applies to a given scenario), the five member syllogism structure (Pancha Avayava), or the types of Hetvabhasas (fallacies).

While one or two questions from this section may seem small, they represent easy marks for those who prepare systematically since many competitors skip this section entirely due to unfamiliarity.

Structure of Arguments: Logical Reasoning

Arguments Forms and Categorical Propositions

Understanding Premises, Conclusions, and Argument Structure

An argument, in logical terms, is not a disagreement or debate. It is a structured set of statements where some statements (called premises) are offered as evidence or reasons to support another statement (called the conclusion).

Every argument you encounter in UGC NET will have this basic structure, and your job is to evaluate whether the premises actually support the conclusion.

Consider this example: “All lawyers are educated. Some educated people are wealthy. Therefore, some lawyers are wealthy.”

Here, the first two sentences are premises, and the third is the conclusion.

The question is whether the conclusion necessarily follows from the premises. In this case, it does not follow necessarily because the “educated people who are wealthy” might not include any lawyers.

The key to analyzing arguments is to separate the premises from the conclusion, identify what each premise claims, and then determine whether accepting all premises as true would force you to accept the conclusion.

This skill of structural analysis is tested repeatedly in UGC NET, sometimes directly and sometimes through Venn diagram or syllogism questions.

Understanding argument structure also helps you identify hidden assumptions. Sometimes an argument’s conclusion requires an unstated premise to be valid. UGC NET questions may ask you to identify this missing premise or to evaluate whether a given conclusion follows when certain assumptions are added.

Practice identifying the logical skeleton of arguments, stripping away the specific content to see the underlying form.

The Four Types of Categorical Propositions (A, E, I, O)

Categorical propositions are statements about categories or classes of things, and they form the building blocks of syllogistic logic.

There are exactly four types, traditionally labeled A, E, I, and O. Type A is universal affirmative (“All S are P”), Type E is universal negative (“No S are P”), Type I is particular affirmative (“Some S are P”), and Type O is particular negative (“Some S are not P”).

Every syllogism in UGC NET will use combinations of these four proposition types.

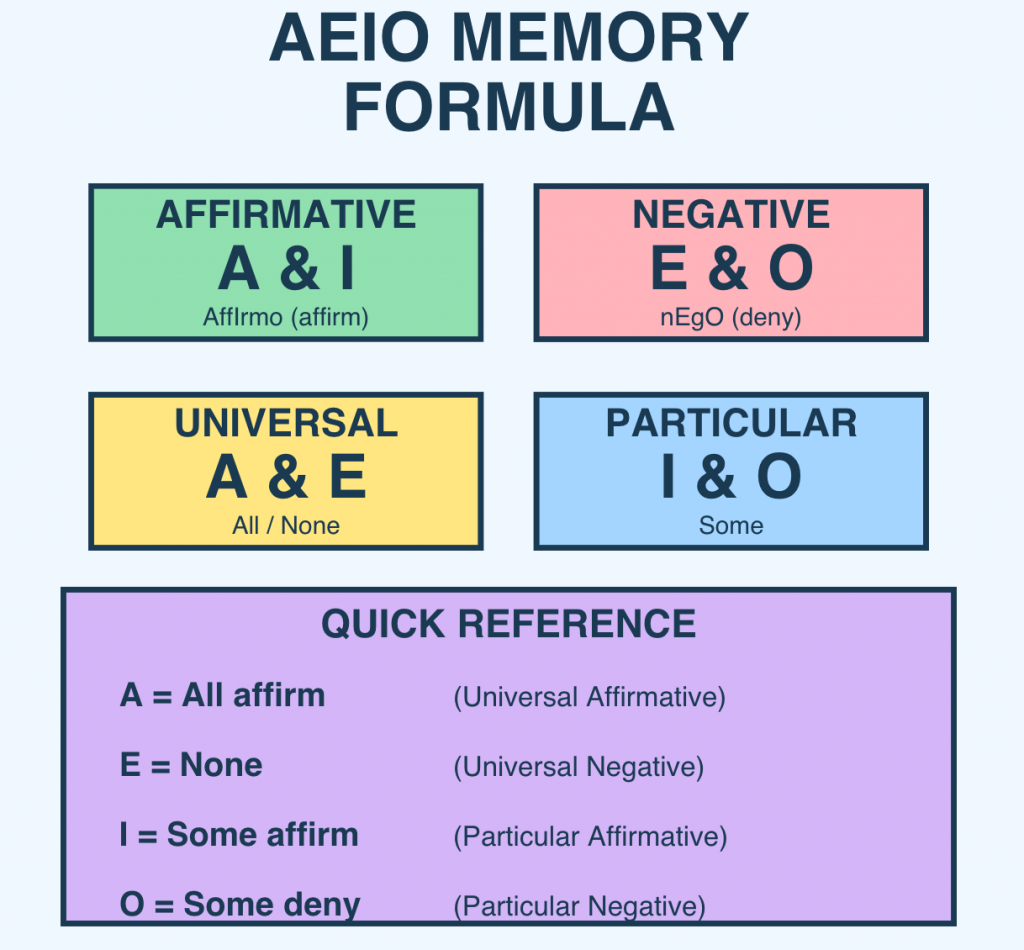

Shortcut: The AEIO Memory Formula

Here is a simple trick to remember the four proposition types:

A and I are affirmative (they assert something positive), while E and O are negative (they deny something). The vowels come from the Latin words “AffIrmo” (I affirm) and “nEgO” (I deny).

Additionally, A and E are universal (they make claims about all members of a class), while I and O are particular (they make claims about some members). This gives you: A = All affirm, E = None (universal negative), I = Some affirm, O = Some deny.

Uses of Language in Logical Arguments

Understanding Descriptive, Evocative, and Directive Uses of Language

Language serves multiple functions beyond simply conveying information. In logical reasoning, understanding these functions helps you evaluate arguments more effectively.

Descriptive use of language aims to convey factual information that can be verified as true or false. When someone says “The UGC NET exam has 150 questions,” they are using language descriptively.

Evocative (or expressive) use of language aims to express or evoke emotions rather than state facts. Saying “UGC NET is a nightmare for unprepared candidates” uses language evocatively.

Directive use of language aims to cause or influence action, such as “You should start your preparation today.” In logical arguments, only descriptive statements can serve as proper premises because only they can be true or false in a factual sense.

Literal vs Figurative Language in Arguments

Literal language means exactly what it says, while figurative language uses metaphors, similes, hyperbole, or other devices to express meaning indirectly. In logical reasoning, figurative language can cause confusion because the same words might have different meanings in different contexts. For example, “He has a heart of stone” is figurative; taking it literally would lead to absurd conclusions.

UGC NET questions may test your ability to distinguish between literal and figurative uses, especially when evaluating whether an argument commits a fallacy. Arguments that treat figurative statements as literal (or vice versa) often contain errors in reasoning. Being attentive to language use helps you identify such errors quickly.

Emotive Language and Its Impact on Reasoning

Emotive language is designed to arouse emotional responses rather than convey neutral information. Words like “freedom fighter” versus “terrorist,” or “budget friendly” versus “cheap,” carry different emotional connotations while potentially referring to the same thing. In logical reasoning, emotive language can distort evaluation because we might accept or reject conclusions based on emotional reactions rather than logical validity.

When analyzing arguments in UGC NET, train yourself to look past emotive language to the actual logical structure. Ask yourself: if I replaced the emotive terms with neutral ones, would the argument still seem valid? This mental exercise helps you evaluate reasoning objectively, which is exactly what the exam tests.

How Language Use Affects Logical Validity?

The validity of an argument depends solely on its logical form, not on the specific words used or their emotional impact. However, ambiguous or vague language can make it difficult to determine an argument’s logical form. When terms are used inconsistently (equivocation) or when their meaning shifts between premises (amphiboly), arguments may appear valid when they are not.

UGC NET tests this understanding by presenting arguments where language use creates apparent but not real logical connections. Your task is to identify when language manipulation, rather than logical structure, creates the appearance of a valid argument. Questions about informal fallacies often rely on this distinction between linguistic appearance and logical reality.

Connotations, Denotations, and the Classical Square of Opposition

Difference Between Connotation and Denotation with Examples

Denotation refers to the literal, dictionary meaning of a term, specifically the set of things to which the term applies. The denotation of “professor” is the class of all professors. Connotation, in contrast, refers to the attributes or characteristics that a term implies. The connotation of “professor” includes attributes like “educated,” “teaches at a university,” “conducts research,” and so on.

Understanding this distinction matters for logical reasoning because terms can have the same denotation but different connotations. “Politician” and “statesman” might refer to the same person, but they carry very different connotations. In syllogistic reasoning, you must focus on denotation (what class of things are we talking about) while being aware of how connotation might mislead you emotionally.

The Square of Opposition: Explained Simply

The Classical Square of Opposition is a diagram that shows the logical relationships between the four types of categorical propositions (A, E, I, O) when they share the same subject and predicate terms. It reveals which propositions can be true together, which must have opposite truth values, and which can both be false. For example, if “All birds are animals” (A) is true, then “No birds are animals” (E) must be false, and “Some birds are animals” (I) must be true.

Shortcut: 4 Rules to Solve Any Square of Opposition Question

Here are four rules that will help you solve any square of opposition question in seconds. Rule 1: Contradictories (A-O and E-I pairs) always have opposite truth values; if one is true, the other must be false, and vice versa. Rule 2: Contraries (A-E pair) cannot both be true, but they can both be false. Rule 3: Subcontraries (I-O pair) cannot both be false, but they can both be true. Rule 4: Subalternation means if A is true, I must be true; if E is true, O must be true.

Memorize these four rules and you can answer any square of opposition question without drawing the diagram. When given a proposition and asked about another, simply identify which relationship applies and apply the corresponding rule. This shortcut can save you valuable time during the exam while ensuring accuracy.

What are Mood and Figure in Logical Arguments?

Understanding the 256 Possible Syllogistic Forms

A categorical syllogism has three categorical propositions: two premises and one conclusion. Since each proposition can be of type A, E, I, or O, and since the arrangement of terms (called the figure) can vary in four ways, there are 4 × 4 × 4 × 4 = 256 possible syllogistic forms. However, only 24 of these forms are valid, meaning only 24 forms guarantee that the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises.

The 24 Valid Syllogistic Forms You Need to Know

The 24 valid syllogisms are distributed across four figures based on the position of the middle term. In Figure 1, there are 4 valid forms (Barbara, Celarent, Darii, Ferio). In Figure 2, there are 4 valid forms (Cesare, Camestres, Festino, Baroco). In Figure 3, there are 6 valid forms (Darapti, Disamis, Datisi, Felapton, Bocardo, Ferison). In Figure 4, there are 5 valid forms (Bramantip, Camenes, Dimaris, Fesapo, Fresison). Some traditions count additional forms under existential import assumptions.

Barbara, Celarent, Darii: Understanding Mnemonic Names for Valid Syllogisms

The medieval logicians created mnemonic names for valid syllogisms, where each vowel in the name indicates the type of proposition. “Barbara” (AAA) means all three propositions are type A: “All M are P, All S are M, therefore All S are P.” “Celarent” (EAE) means: E premise, A premise, E conclusion. “Darii” (AII) means: A premise, I premise, I conclusion.

You do not need to memorize all 24 names for UGC NET, but understanding how the naming system works helps you verify validity quickly. If you can identify the mood (the sequence of proposition types) and figure (the arrangement of terms), you can check against the list of valid forms. Most UGC NET questions will involve the more common forms from Figures 1 and 2.

Quick Identification Tricks for Mood and Figure

To quickly identify the figure of a syllogism, focus on the position of the middle term (the term that appears in both premises but not in the conclusion). In Figure 1, the middle term is subject of the major premise and predicate of the minor premise. In Figure 2, it is predicate in both premises. In Figure 3, it is subject in both premises. In Figure 4, it is predicate of the major premise and subject of the minor premise. With practice, you can identify the figure at a glance and then verify the mood to check validity.

How to Identify Formal and Informal Fallacies?

Common Formal Fallacies with Examples

Formal fallacies are errors in the logical structure of an argument that make it invalid regardless of content. The most common formal fallacy in syllogisms is the “undistributed middle,” where the middle term is not distributed (not referring to all members of its class) in at least one premise.

For example: “All cats are animals, all dogs are animals, therefore all cats are dogs” commits this fallacy because “animals” is never distributed. Other formal fallacies include “illicit major,” “illicit minor,” and “exclusive premises.”

Informal Fallacies: Ad Hominem, Straw Man, and More

Informal fallacies are errors in reasoning that cannot be detected by examining logical form alone; they require understanding the content and context. Ad Hominem attacks the person making an argument rather than the argument itself. Straw Man misrepresents someone’s argument to make it easier to attack.

Appeal to Authority relies on an expert’s opinion in matters outside their expertise. Red Herring introduces irrelevant topics to divert attention. Begging the Question assumes the conclusion in the premises. UGC NET frequently tests your ability to identify these fallacies in given arguments.

The “Red Flag” Method for Spotting Fallacies in 30 Seconds

Look for these red flags when evaluating arguments for fallacies: personal attacks instead of addressing the argument (Ad Hominem), extreme or exaggerated versions of the original position (Straw Man), emotional manipulation or fear tactics (Appeal to Emotion), circular reasoning where the conclusion restates a premise (Begging the Question), irrelevant digressions from the main topic (Red Herring), and false either or choices when other options exist (False Dilemma). Spotting these patterns quickly can help you identify the correct answer even before fully analyzing the argument.

Difference between Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

Deductive Reasoning

- Characteristics of Deductive Arguments

Deductive reasoning moves from general principles to specific conclusions. The defining characteristic of deductive arguments is that if the premises are true and the argument form is valid, the conclusion must necessarily be true.

There is no possibility of the conclusion being false if the premises are true and the reasoning is valid. This certainty is what distinguishes deductive from inductive reasoning.

Common forms of deductive reasoning include syllogisms, mathematical proofs, and arguments from definitions.

When you encounter an argument that claims its conclusion follows necessarily and with certainty from its premises, you are dealing with a deductive argument. UGC NET tests your ability to recognize this characteristic and evaluate whether specific arguments actually achieve deductive validity.

- Valid vs Sound Arguments: The Critical Difference

A valid deductive argument has a correct logical form where the conclusion follows necessarily from the premises, but this says nothing about whether the premises are actually true. A sound argument is both valid AND has true premises.

For example: “All unicorns are purple, this is a unicorn, therefore this is purple” is valid (the form is correct) but not sound (unicorns do not exist, so the premises are false).

UGC NET often tests this distinction by presenting arguments that are valid but clearly unsound, or by asking you to evaluate validity without considering premise truth. Remember: validity is about form; soundness is about form plus truth. When asked about validity, focus only on whether the conclusion follows from the premises, not on whether the premises are actually true in the real world.

- Common Deductive Reasoning Patterns in UGC NET

The most frequently tested deductive patterns in UGC NET include categorical syllogisms (All A are B, All B are C, therefore All A are C), hypothetical syllogisms (If P then Q, If Q then R, therefore If P then R), disjunctive syllogisms (Either P or Q, Not P, therefore Q), and modus ponens (If P then Q, P, therefore Q).

Recognizing these patterns helps you quickly identify valid argument forms and spot when an argument deviates from a valid pattern.

These patterns form the foundation of deductive logic, and UGC NET questions often present variations or test whether you can distinguish valid patterns from superficially similar but invalid ones.

For instance, “If P then Q, Q, therefore P” looks similar to modus ponens but commits the formal fallacy of “affirming the consequent.”

Inductive Reasoning

- Characteristics of Inductive Arguments

Inductive reasoning moves from specific observations to general conclusions. Unlike deductive arguments, inductive arguments do not guarantee their conclusions; they only make the conclusions more or less probable.

Even if all premises of an inductive argument are true, the conclusion might still be false. This is because inductive reasoning involves a “leap” from observed cases to unobserved cases or general principles.

Common forms of inductive reasoning include generalization from samples (surveying 1000 voters to predict election outcomes), analogical reasoning (this medication worked for similar patients, so it will likely work for this patient), and causal reasoning (the floor is wet and it rained, so the rain probably caused the wet floor).

UGC NET tests your understanding of when reasoning is inductive versus deductive.

- Strong vs Weak Inductive Arguments

Since inductive arguments cannot be “valid” or “invalid” in the deductive sense, we evaluate them as “strong” or “weak” based on how much support the premises provide for the conclusion.

A strong inductive argument is one where, if the premises are true, the conclusion is very probably true. A weak inductive argument is one where the premises, even if true, do not make the conclusion very probable.

Factors that strengthen inductive arguments include larger sample sizes, representative samples, absence of counterexamples, and the degree of similarity in analogical reasoning.

For UGC NET, understand that inductive arguments are evaluated on a spectrum of strength rather than a binary valid/invalid distinction. Questions may ask you to compare the relative strength of different inductive arguments.

Recognizing Inductive Patterns in Exam Questions

When a question presents reasoning that moves from specific cases to general claims, or from past observations to future predictions, or from known cases to similar unknown cases, you are dealing with inductive reasoning.

Key phrases that signal inductive arguments include “probably,” “likely,” “most,” “generally,” “tends to,” and “in most cases.” If an argument’s conclusion could possibly be false even when all premises are true, it is inductive.

Side by Side Comparison of Deductive and Inductive Reasoning

| Feature | Deductive Reasoning | Inductive Reasoning |

| Direction | General to specific | Specific to general |

| Certainty | Conclusion is certain (if valid) | Conclusion is probable |

| Evaluation | Valid/Invalid, Sound/Unsound | Strong/Weak, Cogent/Uncogent |

| Conclusion | Cannot exceed premises | Goes beyond premises |

| Example | All humans are mortal; Socrates is human; therefore Socrates is mortal | The sun has risen every day; therefore the sun will rise tomorrow |

This table provides a quick reference for distinguishing between the two types of reasoning. In UGC NET, being able to classify an argument quickly allows you to apply the appropriate evaluation criteria and avoid common errors.

The “Direction of Logic” Shortcut

Remember this simple rule: deductive reasoning moves “downward” from general principles to specific applications, while inductive reasoning moves “upward” from specific observations to general conclusions.

Think of it as D for Deductive and D for Down (general to specific), and I for Inductive and I for Increase (building up from specifics to generals). This mental image can help you quickly classify arguments during the exam.

Sample questions on Inductive and Deductive Reasoning

Question 1: Inductive Reasoning

A researcher observes the following pattern while studying publication trends:

- In 2018, 20% of papers in a journal were interdisciplinary.

- In 2019, 25% of papers were interdisciplinary.

- In 2020, 30% of papers were interdisciplinary.

- In 2021, 35% of papers were interdisciplinary.

Based on inductive reasoning, which of the following conclusions is most logically justified?

A. Interdisciplinary research will dominate all academic journals in the future.

B. The journal shows a consistent annual increase of 5% in interdisciplinary papers.

C. Interdisciplinary research is superior to disciplinary research.

D. All journals will follow the same publication trend.

Correct Answer – B

Explanation (UGC NET JRF approach)

- Inductive reasoning moves from specific observations to a general but probable conclusion.

- The data shows a repeated and consistent increase of 5% each year.

- Option B is a carefully drawn generalisation, limited strictly to the observed data.

- Options A, C, and D go beyond the evidence and make overgeneralised or value-based claims, which inductive reasoning does not justify.

Key JRF Tip:

Induction supports probability, not certainty or sweeping universals.

Question 2: Deductive Reasoning

Consider the following statements:

- No qualitative research study is free from researcher bias.

- All ethnographic studies are qualitative research studies.

Which of the following conclusions must necessarily follow?

A. All ethnographic studies are free from researcher bias.

B. Some qualitative research studies are ethnographic.

C. No ethnographic study is free from researcher bias.

D. Quantitative research studies are free from researcher bias.

Correct Answer – C

Explanation

- This is a deductive categorical reasoning problem involving universal negatives and affirmatives.

- The structure is:

- No A is B

- All C are A

- ∴ No C is B

- Applying it here:

- No qualitative study → free from bias

- All ethnographic studies → qualitative

- Therefore, no ethnographic study is free from researcher bias

- Option C follows inevitably from the premises.

- Options A and D directly contradict the given statements.

- Option B may be factually true in real life, but it does not logically follow from the premises — deduction cares only about logical necessity, not plausibility.

How to Solve Venn Diagram Questions

Venn diagrams are visual representations of categorical propositions and their relationships using overlapping circles.

Each circle represents a category or class, and the overlapping regions represent the intersection of classes.

They were popularized by John Venn in the 1880s as a tool for testing the validity of syllogisms, and they remain the most intuitive method for evaluating categorical arguments.

In UGC NET, Venn diagrams serve as a powerful tool for testing whether a conclusion follows necessarily from given premises. By diagramming the premises and then checking whether the conclusion is automatically represented in the diagram, you can determine validity with certainty.

This visual approach is often faster and less error prone than trying to apply abstract validity rules mentally.

Two Circle vs Three Circle Diagrams

Two circle Venn diagrams are used to represent single categorical propositions and to analyze immediate inferences (conclusions drawn from a single premise).

Three circle diagrams are used to test the validity of syllogisms, which involve two premises and a conclusion. The three circles represent the three terms of the syllogism: the major term (P), the minor term (S), and the middle term (M).

For UGC NET, you need to be comfortable with both types. Two circle diagrams are simpler and are used for square of opposition questions and single premise inferences. Three circle diagrams are more complex but are essential for syllogism questions. The key is to practice drawing them quickly and accurately, as speed matters during the exam.

Shading and Marking Conventions

In Venn diagrams, shading indicates that a region is empty (no members exist in that category intersection).

Placing an X indicates that at least one member exists in that region. These conventions are crucial for representing the four types of categorical propositions.

For A propositions (All S are P), shade the part of S that is outside P. For E propositions (No S are P), shade the overlap between S and P. For I propositions (Some S are P), place an X in the overlap. For O propositions (Some S are not P), place an X in the part of S outside P.

Understanding these conventions is essential because errors in shading or marking lead to incorrect validity judgments.

When an X must be placed in a region that spans multiple areas (because the premises do not specify exactly where in that region the member exists), place the X on the boundary line. This represents uncertainty about the exact location within the permitted region.

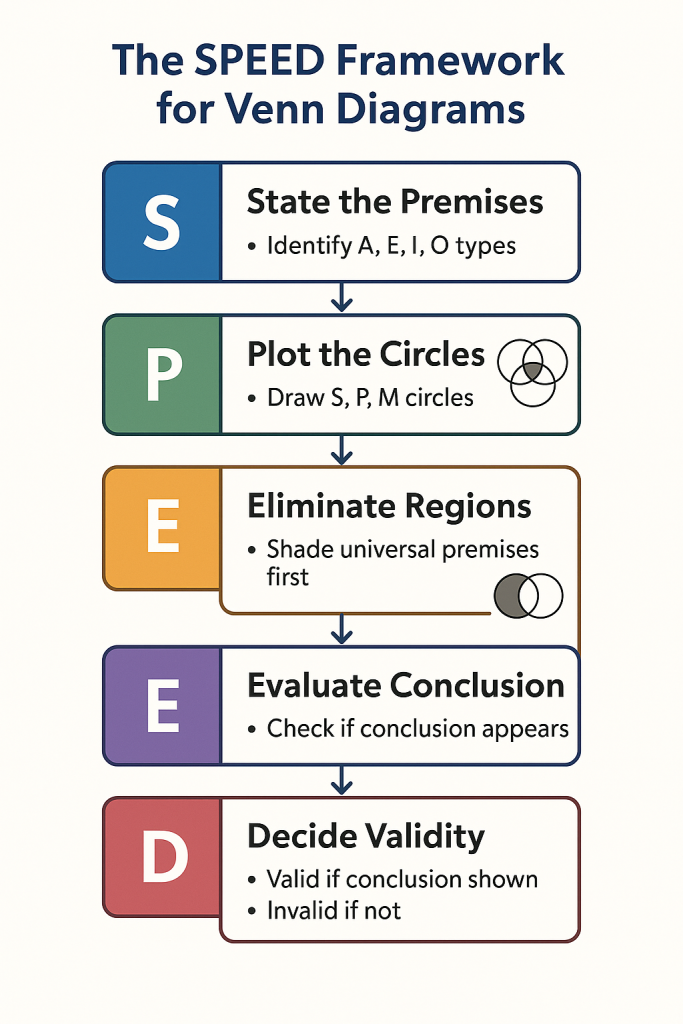

The SPEED Framework for Solving Venn Diagram Questions

S: State the Premises Clearly

Before drawing anything, write out the premises in standard categorical form. Identify each premise as A, E, I, or O type.

Identify the three terms: major term (predicate of conclusion), minor term (subject of conclusion), and middle term (appears in both premises but not in conclusion).

This preparation takes only seconds but prevents costly errors in the diagramming process.

P: Plot the Circles Systematically

Draw three overlapping circles with consistent positioning: the minor term (S) on the left, the major term (P) on the right, and the middle term (M) at the top or bottom. Label each circle clearly.

This consistent positioning helps you diagram quickly without confusion about which region represents which intersection of terms.

E: Eliminate Invalid Regions Through Shading

Diagram the universal premises first (A and E types) by shading the appropriate regions. Shading eliminates regions as possibilities, which constrains where X marks can be placed for particular premises.

Always shade before marking X, because shading might eliminate some areas that would otherwise be options for your X placement.

E: Evaluate the Conclusion

After diagramming both premises, examine the diagram without adding anything for the conclusion.

Ask: does the diagram already show the conclusion? For a valid syllogism, the conclusion should be automatically represented in the diagram through the premises alone.

If the conclusion is a universal statement, check whether the required shading is present. If the conclusion is particular, check whether an X exists in the required region.

D: Decide Validity

If the conclusion appears in the diagram, the argument is valid. If the conclusion does not appear, or if the diagram allows for situations where the conclusion would be false, the argument is invalid.

Remember that you should not add anything to the diagram for the conclusion; you are only checking whether the premises, when diagrammed, already entail the conclusion.

Establishing Validity of Arguments Using Venn Diagrams

Testing Categorical Syllogisms Step by Step

Let us walk through a complete example.

Consider: “All lawyers are educated people. All educated people read books. Therefore, all lawyers read books.”

- Step 1: Identify terms: S = lawyers, P = read books, M = educated people.

- Step 2: Identify premises: “All lawyers are educated people” is type A (All S are M). “All educated people read books” is type A (All M are P).

- Step 3: Draw three circles and diagram both A propositions by shading.

- Step 4: Check if “All S are P” appears. Since the part of S outside P is shaded, the conclusion is represented. The argument is valid.

Here is an invalid example: “Some politicians are honest. All honest people are respected. Therefore, all politicians are respected.”

- Step 1: S = politicians, P = respected, M = honest.

- Step 2: First premise is type I (Some S are M), second premise is type A (All M are P).

- Step 3: Diagram by shading for the A premise, then placing X for the I premise.

- Step 4: Check if “All S are P” appears. It does not, because there is unshaded region in S outside P. The argument is invalid.

Common Venn Diagram Patterns in UGC NET

Certain patterns appear repeatedly in UGC NET Venn diagram questions.

The “Barbara” pattern (AAA-1) is frequently tested: All M are P, All S are M, therefore All S are P. This is valid.

The “undistributed middle” error is often presented: All P are M, All S are M, therefore All S are P. This is invalid because M is not distributed.

Questions may also test your ability to find the valid conclusion when given two premises, requiring you to diagram and then identify which of the given options appears in the diagram.

Another common pattern involves immediate inferences from the square of opposition.

Given that a proposition is true or false, you may be asked to determine the truth value of related propositions. While you can use the square of opposition rules directly, diagramming provides a visual confirmation of your answer.

How to Solve Analogy Questions Quickly?

What are Analogies in Logical Reasoning?

Definition of Analogies

An analogy is a comparison between two things based on their similarity in certain respects, used to explain or clarify something or to form the basis of an argument.

In logical reasoning, analogy questions test your ability to recognize relationships between pairs of concepts and apply the same relationship to new pairs.

The underlying skill is pattern recognition: identifying the specific type of relationship in a given pair and finding or completing a parallel pair.

Types of Analogies: Word Analogy, Number Analogy and Letter Analogy

Analogies appear in UGC NET in various formats.

Word analogies test your vocabulary and conceptual understanding. The relationship might be synonymous (happy : joyful), antonymous (hot : cold), part to whole (wheel : car), cause to effect (virus : disease), or many other types. Success requires both recognizing the relationship type and having sufficient vocabulary to evaluate options.

Number analogies test your ability to recognize mathematical relationships between numbers, such as sequences, proportions, or operations.

Letter analogies test pattern recognition in alphabetical sequences, such as letter positions, skipping patterns, or reverse alphabets.

While these types might seem different, they all require the same core skill: identifying the pattern or relationship and applying it consistently.

Pattern Recognition Techniques for Analogies

Common Relationship Types (Synonym, Antonym, Part Whole, etc.)

The most common relationship types in UGC NET analogies include:

Synonyms (words with similar meanings), Antonyms (words with opposite meanings), Part to Whole (component : complete object), Whole to Part (complete object : component), Cause to Effect (action : result), Object to Function (tool : what it does), Object to Characteristic (thing : its quality), Category to Member (group : individual), Worker to Workplace (profession : location), and Degree (mild : extreme form).

Familiarity with these common types allows you to quickly categorize relationships and eliminate incorrect options.

When you see a pair, immediately try to fit it into one of these categories. Most UGC NET analogy questions use these standard relationship types, so recognizing them quickly gives you a significant advantage.

The “Bridge Sentence” Method

Create a simple sentence that connects the two terms of the given pair, then apply the same sentence structure to the answer options.

For example, if the pair is “Doctor : Hospital,” your bridge sentence might be “A Doctor works in a Hospital.” Then test each option: “Teacher : School” fits (A Teacher works in a School), but “Book : Library” does not fit the same way (A Book does not work in a Library).

This method ensures you are comparing the exact relationship, not just superficial similarities.

Shortcut: Identifying the Relationship Before Looking at Options

Train yourself to determine the relationship type before reading the answer options. This prevents you from being misled by attractive but incorrect options.

Read the given pair, mentally identify the relationship, articulate it clearly (even if just in your head), and only then look at the options to find a match.

This disciplined approach prevents the common error of choosing an option that seems vaguely related rather than precisely parallel.

Practice Strategies for Analogy Questions

Building Your Analogy Vocabulary

Strong vocabulary is essential for word analogies.

Read widely, make note of new words, and specifically study common analogy pairs that have appeared in previous UGC NET papers.

Many coaching resources provide lists of frequently tested word pairs, which can be valuable for last minute revision. However, understanding relationships matters more than memorizing specific pairs, so focus on the underlying logic rather than rote learning.

Time Management for Analogy Questions

Analogy questions should be relatively quick if you have prepared well. Aim to solve each analogy question in 30 to 45 seconds. If a question is taking longer, it may be due to unfamiliar vocabulary, in which case make your best guess and move on.

Do not let a single difficult analogy question consume time that could be used for other questions. Mark it for review and return if time permits at the end.

Indian Logic and Pramanas: Guide to Nyaya Philosophy for UGC NET

Indian Logic, particularly as developed in the Nyaya school of philosophy, represents one of humanity’s oldest and most sophisticated logical traditions.

The Nyaya school, founded by the sage Gautama (also known as Akshapada) around 2nd century BCE, developed a comprehensive system for understanding valid knowledge, correct reasoning, and logical debate.

The term “Nyaya” itself means “rule” or “method,” reflecting its focus on systematic procedures for reasoning.

At its core, Nyaya philosophy addresses a fundamental question: how do we know what we know?

The answer involves analyzing the sources or means through which we acquire valid knowledge, called Pramanas.

This epistemological focus makes Nyaya directly relevant to understanding logic and reasoning, which is why UGC incorporated these topics into the Paper 1 syllabus to give aspirants exposure to India’s rich logical heritage.

How Indian Logic Differs from Western Logic?

While Western formal logic, developed from Aristotle through modern symbolic logic, focuses primarily on the forms of valid arguments, Indian logic takes a broader approach that includes epistemology (theory of knowledge) alongside logic proper.

Western logic asks: “Is this argument valid?” Indian logic asks: “Is this knowledge valid, and through what means was it obtained?”

Another key difference is in the structure of inference. Western syllogisms typically have three parts (major premise, minor premise, conclusion), while the Indian inference model (Nyaya’s Pancha Avayava or five membered syllogism) has five parts that explicitly include examples and application.

This difference reflects a pedagogical orientation: Indian logic was developed partly for debate and teaching, so it includes elements that make arguments more persuasive and understandable, not just formally valid.

Why This Topic Intimidates Aspirants (And Why It Shouldn’t)?

The primary reason aspirants find Indian Logic intimidating is the Sanskrit terminology.

Terms like “Pratyaksha,” “Anumana,” “Vyapti,” and “Hetvabhasas” sound foreign and complex.

However, the underlying concepts are quite intuitive once explained in familiar terms.

Pratyaksha is simply perception. Anumana is inference. Vyapti is the invariable connection between two things (like smoke and fire). Hetvabhasas are fallacies.

The concepts themselves are not difficult; only the vocabulary is unfamiliar. With a systematic approach, you can master this section in a few days.

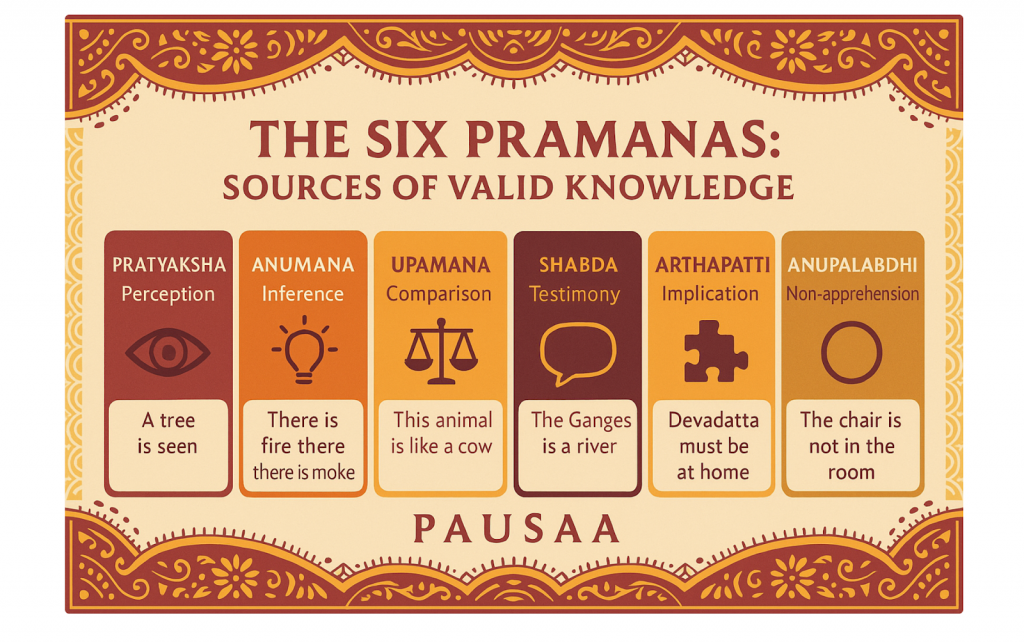

What are the Six Types of Pramanas (Means of Knowledge)?

Pratyaksha (Perception): Direct Knowledge Through Senses

Pratyaksha is direct perception through the senses (sight, hearing, smell, taste, touch) or the mind. When you see a red apple, your knowledge of “this is a red apple” comes through Pratyaksha.

It is considered the most fundamental Pramana because other means of knowledge ultimately depend on perceptual experience. In UGC NET, questions may ask you to identify which Pramana applies to scenarios involving direct observation or sensory experience.

Anumana (Inference): Knowledge Through Logical Reasoning

Anumana is knowledge obtained through inference or reasoning from what is perceived to what is not directly perceived.

The classic example is inferring fire on a distant hill from seeing smoke. You perceive smoke (directly) and infer fire (indirectly) based on the known relationship between smoke and fire. Anumana is the Pramana most closely related to Western logical reasoning.

Upamana (Comparison): Knowledge Through Analogy

Upamana is knowledge gained through comparison or analogy. If someone tells you that a wild ox (gavaya) looks like a cow, and you later encounter an animal that resembles a cow, you know it is a gavaya through Upamana.

This Pramana involves learning about unknown things by comparing them to known things. It is similar to analogical reasoning in Western logic.

Shabda (Verbal Testimony): Knowledge Through Reliable Sources

Shabda is knowledge obtained from reliable verbal testimony, whether spoken or written. This includes knowledge from authoritative texts, trustworthy experts, or reliable witnesses.

The key requirement is that the source must be credible and trustworthy. In everyday life, we acquire vast amounts of knowledge through Shabda: from textbooks, news sources, teachers, and so on.

Arthapatti (Implication): Knowledge Through Presumption

Arthapatti is knowledge obtained through presumption or postulation to explain an apparent contradiction or inexplicable fact.

For example, if you know that Devadatta is alive and healthy but never eats during the day, you presume (through Arthapatti) that he must eat at night. This postulation is necessary to reconcile the facts. It is similar to inference but specifically involves resolving contradictions through presumption.

Anupalabdhi (Non Apprehension): Knowledge Through Absence

Anupalabdhi is knowledge of the absence of something, obtained through not perceiving it where it should be perceivable if it existed. When you look at a table and do not see a book, you know (through Anupalabdhi) that there is no book on the table.

This Pramana recognizes that knowledge of absence is a distinct type of knowledge, not merely the failure of perception.

Memory Trick: The “PAUSAA” Formula for All 6 Pramanas

Use the mnemonic “PAUSAA” to remember all six Pramanas: P for Pratyaksha (Perception), A for Anumana (Inference), U for Upamana (Comparison), S for Shabda (Verbal testimony), A for Arthapatti (Implication), A for Anupalabdhi (Non apprehension).

This simple formula ensures you can recall all six during the exam.

Additionally, remember that different Indian philosophical schools accept different numbers of Pramanas: Charvaka accepts only 1 (Pratyaksha), Vaisheshika and Buddhism accept 2, Sankhya accepts 3, Nyaya accepts 4, and Vedanta accepts 6.

What is the Structure and Kinds of Anumana (Inference)?

The Five Member Syllogism (Pancha Avayava)

Indian inference (Anumana) is expressed through a five membered structure called Pancha Avayava. The five members are: Pratijna (proposition or thesis to be proved), Hetu (reason or middle term), Udaharana (example illustrating the universal rule), Upanaya (application of the rule to the case at hand), and Nigamana (conclusion restating the thesis).

This structure is more elaborate than the Western three part syllogism because it explicitly includes an example and application step for clarity in debate.

Paksha, Hetu, and Sadhya Explained Simply

In Indian logic, the three key terms of inference are Paksha (the subject or minor term, like “the hill”), Sadhya (the property to be proved or major term, like “fiery”), and Hetu (the reason or middle term, like “because of smoke”).

A complete inference states: “The hill (Paksha) has fire (Sadhya) because it has smoke (Hetu).” Understanding these terms helps you analyze inference structures in UGC NET questions.

Types of Anumana: Purvavat, Sheshavat, and Samanyatodrista

Anumana is classified into types based on the direction of inference. Purvavat is inference from cause to effect (seeing dark clouds, inferring future rain). Sheshavat is inference from effect to cause (seeing a river swollen, inferring past rain in the mountains). Samanyatodrista is inference based on general correlation without a causal relationship (seeing a particular star position, inferring the time of year). These classifications help in analyzing the type of reasoning involved in different inference scenarios.

Svartha Anumana vs Parartha Anumana

Anumana is also classified based on its purpose. Svartha Anumana (inference for oneself) is when a person reasons privately to arrive at knowledge for their own understanding. Parartha Anumana (inference for others) is when the reasoning is expressed formally to convince others in debate.

What is Vyapti (Invariable Relation)?

Understanding Vyapti with the Smoke Fire Example

Vyapti is the invariable concomitance or universal relationship between the Hetu (reason) and Sadhya (what is to be proved). It is the foundation of valid inference. The classic example is the Vyapti between smoke and fire: “Wherever there is smoke, there is fire.”

This universal relationship allows us to infer fire from smoke. Without Vyapti, inference would not be possible because we could not move from what we observe to what we do not observe.

Sama Vyapti vs Visama Vyapti

Vyapti can be of two types based on the extent of the relationship. Sama Vyapti (equipollent concomitance) exists when the two terms have equal extension, meaning each implies the other.

For example, “nameable” and “knowable” have Sama Vyapti because everything nameable is knowable and everything knowable is nameable. Visama Vyapti (non equipollent concomitance) exists when one term has wider extension than the other.

Smoke and fire have Visama Vyapti: wherever there is smoke, there is fire, but not wherever there is fire, there is smoke (red hot iron has fire without smoke).

How to Identify Vyapti in Exam Questions?

UGC NET questions may ask you to identify whether a Vyapti relationship exists between given terms or to find examples where Vyapti holds or fails. The key test is universality: ask whether the relationship holds in ALL cases without exception.

If you can think of a counter example, the Vyapti does not hold. Smoke implies fire, but fire does not always produce smoke, so the Vyapti is one directional (Visama). Understanding this helps you evaluate inference validity in exam questions.

What are Hetvabhasas (Fallacies of Inference)?

The Five Types of Hetvabhasas

Hetvabhasas are fallacies or defective reasons that make an inference invalid. The Nyaya school identifies five main types: Savyabhichara (irregular or inconclusive reason), Viruddha (contradictory reason), Asiddha (unproved reason), Satpratipaksha (counterbalanced reason), and Badhita (contradicted reason).

These correspond roughly to various fallacies recognized in Western logic but are classified based on how the reason (Hetu) fails to support the conclusion.

Savyabhichara (Irregular Reason)

Savyabhichara occurs when the reason is inconclusive because it is also found where the Sadhya is absent.

For example: “The hill has fire because it has smoke” is valid. But “Sound is eternal because it is knowable” is fallacious because knowability is found in both eternal things (like space) and non eternal things (like a pot). The reason “knowable” does not invariably lead to “eternal,” making it irregular.

Viruddha (Contradictory Reason)

Viruddha occurs when the reason actually proves the opposite of what is claimed. For example: “Sound is eternal because it is produced” is contradictory because production actually implies non eternality. Things that are produced come into being at a point in time, which is the opposite of eternal. The reason given proves the opposite of the thesis.

Asiddha (Unproved Reason)

Asiddha occurs when the reason itself is not established or is doubtful. This can happen in three ways: the locus (Paksha) does not exist (e.g., “the sky flower is fragrant because it has lotuses in it” where sky flowers do not exist), the reason is not present in the locus, or the reason is only partially present. If we cannot confirm that the reason actually exists in the subject, the inference fails.

Satpratipaksha (Counterbalanced Reason)

Satpratipaksha occurs when there is an equally strong counter reason that proves the opposite conclusion. For example, “Sound is eternal because it is audible” might be countered by “Sound is non eternal because it is produced.” Both reasons have equal force, so they cancel each other out, and no conclusion can be drawn.

This fallacy arises in debates where both sides present equally valid seeming reasons.

Badhita (Contradicted Reason)

Badhita occurs when the reason, even if valid in form, is contradicted by stronger evidence from another Pramana. For example, if someone argues “Fire is cold because it is a substance,” this is contradicted by direct perception (Pratyaksha) that fire is hot.

Even though the syllogistic form might be correct, the conclusion is known to be false through more direct means, making the reason inadmissible.

Quick Reference Table for All Hetvabhasas

| Hetvabhasa | Meaning | Example | Western Equivalent |

| Savyabhichara | Irregular reason | “X is eternal because knowable” | Undistributed middle |

| Viruddha | Contradictory reason | “Sound eternal because produced” | Self contradiction |

| Asiddha | Unproved reason | Reason in non existent subject | Begging the question |

| Satpratipaksha | Counterbalanced reason | Equal opposite reasons exist | Equal and opposite |

| Badhita | Contradicted reason | Contradicts perception | Contradiction by evidence |

This table provides a quick reference for exam preparation. When facing questions about Hetvabhasas, identify which type of failure is present in the given inference.

Best Books and Resources for Logical Reasoning

Recommended Books for Western Logic

For Western Logic, “A Modern Introduction to Logic” by L. Susan Stebbing provides excellent coverage of syllogisms and argument structure. “Introduction to Logic” by Irving M. Copi is another classic that covers formal and informal fallacies comprehensively.

For exam focused preparation, Trueman’s UGC NET Paper I guide includes solved examples and practice questions specifically aligned with the UGC NET pattern.

R.S. Aggarwal Verbal & Non Verbal Reasoning” or “M.K. Pandey Analytical Reasoning” for extra Venn diagram and syllogism practice are very popular among UGC aspirants.

Recommended Books for Indian Logic

For Indian Logic, “A Primer of Indian Logic” by S.C. Vidyabhusana offers a beginner friendly introduction to Nyaya concepts. “Indian Logic” by B.K. Matilal provides more depth for those who want thorough understanding. The NCERT textbooks on Philosophy for Class 11 and 12 also cover Pramanas in accessible language and are available free on the NCERT website.

Conclusion

Logical Reasoning in UGC NET Paper I is not the intimidating monster that many aspirants imagine. With systematic preparation, clear understanding of concepts, and regular practice, this unit can become one of your most reliable scoring areas.

Remember that the syllabus covers two broad traditions: Western Logic (arguments, syllogisms, Venn diagrams, fallacies) and Indian Logic (Pramanas, Anumana, Vyapti, Hetvabhasas). Both require understanding rather than rote memorization, and both reward practice.

The shortcuts and frameworks we have covered, including the AEIO proposition system, the four square of opposition rules, the SPEED method for Venn diagrams, the PAUSAA mnemonic for Pramanas, and the five Hetvabhasas, provide you with tools for quick and accurate problem solving. These are not just memory tricks; they represent efficient approaches to question types that appear repeatedly in UGC NET.

Your next step is simple: start practicing today. Download previous year papers, attempt the Logical Reasoning questions, check your accuracy, and analyze your mistakes. Consistent practice over 2 to 3 weeks will transform your comfort level with this unit.

For comprehensive preparation across all Paper 1 units, explore other UGC NET preparation resources on LawSikho that cover Teaching Aptitude, Research Methodology, Higher Education, and more. Your journey to qualifying UGC NET begins with mastering one unit at a time, and Logical Reasoning is an excellent place to start.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many questions come from Logical Reasoning in UGC NET Paper I?

Logical Reasoning typically contributes 5 questions in each UGC NET exam session. With each question carrying 2 marks, this translates to 10 marks, representing approximately 10 percent of the total Paper I score of 100 marks.

Is Indian Logic difficult to prepare for UGC NET?

Indian Logic is not inherently difficult; the challenge lies in unfamiliar Sanskrit terminology. Once you understand the terms (Pramana means source of knowledge, Anumana means inference, etc.), the concepts are quite intuitive. Most aspirants can master this section in 3 to 5 days of focused study.

Can I skip Indian Logic and still score well in Logical Reasoning?

Skipping Indian Logic is not recommended as it typically contributes 1 to 2 questions (2 to 4 marks) per exam. Since many candidates skip this section, preparing for it gives you a competitive advantage. The investment of 3 to 5 days can yield guaranteed marks that others leave on the table.

Do I need a philosophy background to understand Indian Logic?

No philosophy background is required. The UGC NET syllabus covers only specific logical concepts from Indian philosophy, not the entire philosophical tradition. With clear explanations and examples, anyone can understand Pramanas, Anumana, and Hetvabhasas regardless of their academic background.

How much time should I spend preparing for Logical Reasoning?

Allocate 2 to 3 weeks for comprehensive Logical Reasoning preparation, with 1.5 to 2 hours of daily study. If you have prior exposure to reasoning from other exams, you may need less time. First time learners should budget the full 3 weeks to build confidence.

Are Venn diagram questions common in UGC NET?

Yes, Venn diagram questions are among the most consistently appearing question types in UGC NET Logical Reasoning. Almost every exam session includes at least 1 to 2 questions that require testing syllogism validity using Venn diagrams. Mastering this topic alone can secure 2 to 4 marks.

What are the most important topics in Logical Reasoning for UGC NET?

Based on previous year analysis, the most important topics are: Venn diagrams for testing syllogism validity, square of opposition and categorical propositions, identifying valid syllogistic forms, the six Pramanas from Indian Logic, and distinguishing deductive from inductive reasoning.

How can I remember all six Pramanas easily?

Use the mnemonic “PAUSAA”: P for Pratyaksha (Perception), A for Anumana (Inference), U for Upamana (Comparison), S for Shabda (Testimony), A for Arthapatti (Implication), A for Anupalabdhi (Non apprehension). Creating personal associations or examples for each Pramana also helps retention.

What is the best way to solve syllogism questions quickly?

The fastest method is the Venn diagram approach using the SPEED framework: State premises, Plot circles, Eliminate regions through shading, Evaluate the conclusion, and Decide validity. With practice, you can solve standard syllogisms in 60 to 90 seconds using this method.

Are there negative marks for wrong answers in Logical Reasoning?

No, there is no negative marking in UGC NET Paper I or Paper II. Each correct answer earns 2 marks, and wrong answers earn zero marks without any penalty. This means you should attempt all questions, even if you need to make educated guesses.

Which books should I refer to for Indian Logic preparation?

“A Primer of Indian Logic” by S.C. Vidyabhusana is excellent for beginners. NCERT Class 11 and 12 Philosophy textbooks also cover Pramanas accessibly. For exam focused preparation, Trueman’s UGC NET Paper I guide includes Indian Logic content aligned with the syllabus.

How do I identify fallacies in arguments during the exam?

Use the “Red Flag” method: look for personal attacks (Ad Hominem), exaggerated versions of arguments (Straw Man), emotional manipulation (Appeal to Emotion), circular reasoning (Begging the Question), or irrelevant diversions (Red Herring). These patterns indicate informal fallacies.

What is the weightage of Logical Reasoning in Paper I?

Logical Reasoning (Unit VI) carries approximately 10 marks out of 100 in Paper I, based on 5 questions appearing per session. Combined with Mathematical Reasoning (Unit V) and Data Interpretation (Unit VII), the reasoning based units contribute roughly 20 to 30 percent of Paper I.

Can I solve Logical Reasoning questions without drawing Venn diagrams?

While experienced test takers can sometimes solve simpler syllogisms mentally, drawing Venn diagrams is strongly recommended for accuracy. Venn diagrams take only 30 to 60 seconds to draw and significantly reduce errors. For complex or unfamiliar syllogisms, diagrams are essential.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications