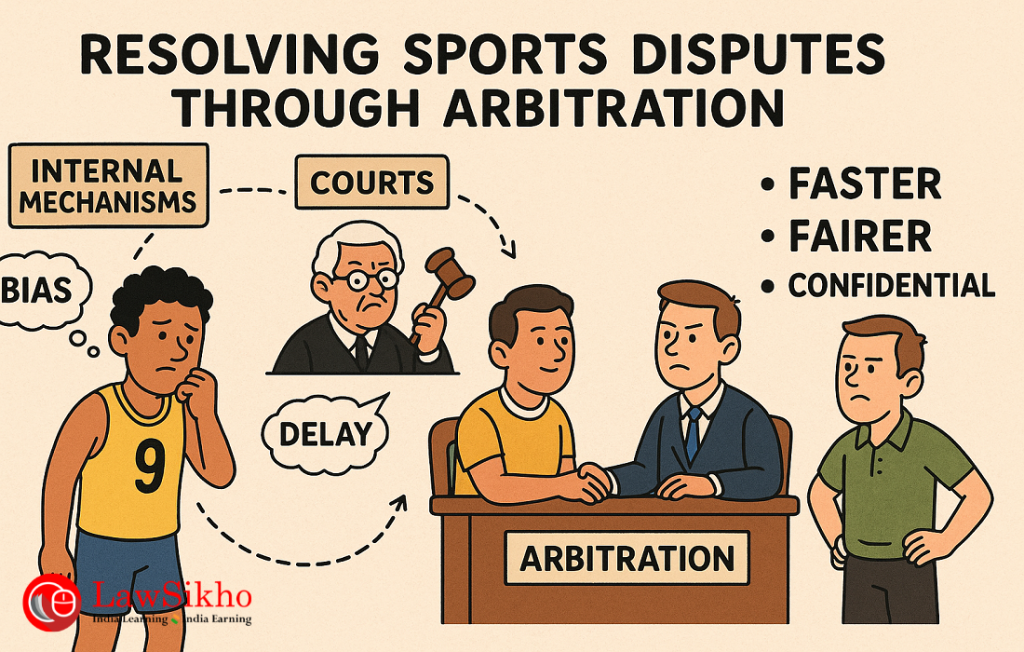

In this guide, I want to walk you through how sports disputes can be resolved through arbitration in India. This article is about understanding your options when a dispute arises, identifying the best route for resolution, and using the arbitration mechanisms available within India, whether institutional or ad hoc. Together, we will explore how internal systems work (and where they fall short), why courts may not always be the best option, and how arbitration done right can offer you clarity, confidentiality, and quicker resolution.

Table of Contents

Introduction

What happens when a game moves off the field?

Not too long ago, I had a conversation with a mutual friend. She is a young sprinter from Kerala. She had missed the national trials due to a last-minute rescheduling. She was replaced without any formal communication. Naturally, she was upset and wanted to challenge the decision.

Now came the dilemma: where do you go when you have a grievance in Indian sport? Do you write to the federation? Do you approach the courts? Or is there a better way?

As someone who has followed sports law and seen it evolve in India, I believe that this confusion is not limited to one athlete or even a few. Unfortunately, so many out there are uninformed.

The truth is that many athletes, coaches, and even clubs in India are not entirely sure how to resolve disputes when they arise. And there are constant disputes all the time.

Whether it is a matter of selection, breach of contract, sponsorship disagreements, or doping allegations, the path to justice often seems as uncertain as the outcome of a close match.

What makes this even more complex is the pace and pressure of competitive sport. Careers are short. Seasons are packed. Reputations can be affected overnight. In traditional litigation, there are delays and formality. It also often feels out of sync with the urgency that sport demands.

This is where arbitration steps in, not as a substitute for justice, but as a way of delivering it more efficiently and fairly.

Let us look at this from a larger perspective.

In the global sporting arena, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Lausanne has long been the go-to forum for resolving high-stakes disputes.

But what about disputes that are rooted in India? Do Indian athletes and clubs have to go all the way to Switzerland? Or is there a way to resolve sports disputes right here, within our legal framework?

To put it simply, yes, there is. There is not only courts and arbitration, but also negotiation, mediation, and conciliation. And all of these are options for anyone who is facing a dispute.

Understanding the landscape of sports disputes in India

Before we dive into arbitration and other mechanisms, we need to take a moment to understand the kinds of disputes that actually arise in Indian sport.

What immediately comes to mind? You may think of doping cases or team selection issues. And yes, they are reasonable ones to think about. But the range is much wider than that. The truth is, sports today are not just about performance on the field. They are actually deeply intertwined with contracts, commercial arrangements, regulatory rules, and the governance structures of federations.

Take, for instance, a dispute between a footballer and a club over unpaid dues. Or a young athlete who challenges their exclusion from a tournament. Or a broadcaster who alleges breach of contract after a federation pulls out of a media deal. These are not hypotheticals. These are real issues that athletes, administrators, and lawyers deal with more often than we talk about.

Broadly, sports disputes in India fall into the following categories:

1. Selection and eligibility disputes

This is perhaps the most emotionally charged area. Being left out of a squad or disqualified from an event can be career-defining. These decisions are often taken by internal committees of federations, sometimes without transparency or proper reasoning. When athletes want to challenge them, they are not always given a clear process.

And when they want to challenge these decisions, they are sometimes left with no options but the internal committee that is set up, and even that does not work out, then they usually just let it go.

2. Disciplinary matters

Then come the ethical issues. This includes doping violations, behavioural issues, code of conduct violations, and match-fixing allegations. Federations usually have disciplinary panels or ethics committees to address such issues. However, these panels are not always independent or well-trained in the due process.

The Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) controversy, involving serious allegations and a breakdown in internal redressal, is a recent example that made headlines for all the wrong reasons.

So what happened here?

In 2023, Vinesh Phogat, Sakshi Malik, and Bajrang Punia accused Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) president Brij Bhushan Sharan Singh of sexual harassment. Keep in mind that these are prominent Indian wrestlers.

The wrestlers did not first approach the WFI’s Internal Complaints Committee.

Why?

At the time, the federation lacked a properly constituted Internal Complaints Committee (ICC). This is as mandated by the Prevention of Sexual Harassment (PoSH) Act. The existing committee had four men and one woman. This was a violation of the legal requirement that such committees be led by a woman and have a majority of female members.

So this left them with no credible internal mechanism to turn to. Instead, they staged a public sit-in protest, prompting the government to form an oversight committee.

However, this committee too was criticised for bias, procedural lapses, and failing to provide a fair hearing, forcing the wrestlers to escalate the matter to the Supreme Court, which eventually directed the registration of FIRs against Singh, including under the POCSO Act.

Like I said, these are famous wrestlers. They are the face of wrestling. And when such a big issue took place, it took extreme measures to get noticed. Now, what about not-so-famous players? What could they do in such a situation?

This is an example of why such internal committees are needed and should be given importance. Such bodies are the first line of defence for addressing grievances sensitively and effectively, preventing harm and ensuring accountability.

When these fail or are absent, aggrieved parties have to look at other options.

ADR can step in here, but involving serious allegations like sexual harassment, criminal and statutory mechanisms remain paramount to ensure justice and systemic reform.

3. Contractual disputes

These involve players, clubs, sponsors, agents, broadcasters, and sometimes even equipment suppliers. Who pays what? What happens if a contract is terminated mid-season? Can a player switch clubs without paying a buy-out fee? Such questions are increasingly common as Indian sport becomes more commercialised.

4. Governance issues

These are disputes relating to the functioning of federations, how elections are held, how funds are used, and how decisions are taken. The Praful Patel-AIFF election case and the suspension of the Indian Olympic Association by the IOC in 2012 are classic examples. These matters may actually seem distant from the playing field, but they affect how sport is run in the country.

5. Ethical and harassment complaints

So this is an area that requires serious attention. In fact, allegations of sexual harassment, abuse of power, and intimidation have emerged across sports. The response of federations is often inconsistent. Because of this, players find it difficult to trust internal systems. The WFI case (explained above) showed how athletes had to protest on the streets before the issue was taken seriously.

6. Doping and regulatory issues

Doping allegations are governed by anti-doping bodies. But enforcement and appeals frequently spill into legal forums. India has a high rate of doping violations, and many cases suffer from procedural lapses. Athletes often lack proper representation in such hearings.

Now, why does this matter? Because each of these categories involves different laws, processes, and timelines. And the choice of forum, whether you go to an internal committee, a court, or an arbitral tribunal, can make a significant difference to the outcome.

What we see today in India is a patchwork system. Some federations have well-structured internal mechanisms. Others rely on ad hoc committees. Yes, courts step in occasionally, but delays are inevitable. Arbitration offers an opportunity to bring order, specialisation, and timeliness to this landscape, which becomes quite important in sports matters.

Now, let us look at how these internal mechanisms work and why they are not always enough.

Internal dispute mechanisms: the first stop

When a dispute arises in Indian sport, the first response is often to turn to the concerned sports federation. That is, of course, understandable. These bodies govern the sport, select the teams, enforce the rules, and maintain the disciplinary framework. Almost every federation in India, whether it is the BCCI for cricket, the AIFF for football, or the WFI for wrestling, has some kind of internal mechanism for resolving disputes.

But how do these mechanisms actually work? And more importantly, do they work well?

What do these internal systems look like?

So, typically, federations have disciplinary committees, ethics officers, or ombudsman-like bodies that are created under their constitution or bylaws.

For example, the BCCI has an Ombudsman and an Ethics Officer to address complaints. Similarly, the AIFF has resolved contractual disputes internally, such as the case involving Chennaiyin FC and a player, which was settled without approaching external forums.

These mechanisms are supposed to offer a quick, sport-specific, and accessible process for athletes and others to raise grievances. Since the panels often consist of members with experience in that sport, there is an assumption that the resolution will be fair and well-informed.

However, the picture is not always so simple.

Where do these systems fall short?

In theory, internal redressal should work well. But in practice, several issues crop up. Let me highlight some of them:

- Lack of independence

Federation panels are often staffed by insider officials who are part of the same body whose decision is under challenge. This creates an obvious conflict of interest. How can you be the judge in your own cause?

- Lack of transparency

Many decisions are taken behind closed doors, with little explanation or reasoning provided. Athletes may not receive a written order. Timelines are unclear. Proceedings are not always recorded. All of this undermines trust.

- Procedural irregularities

There is often no formalised process for filing a complaint or appeal. Even when there is, the process may not follow principles of natural justice. You may not be given a chance to be heard. You may not even know the full case against you.

- Bias and arbitrariness

Since federation officials often wear multiple hats, selector, administrator, and finance head, the process becomes vulnerable to bias. This is especially serious in cases involving selection or disciplinary action.

- No real enforcement power

Even if a panel rules in favour of an athlete, there is no guarantee of enforcement. The federation may ignore or delay the implementation. There is no external oversight.

Real examples of breakdown

We already looked at the Wrestling Federation of India (WFI) example.

Similarly, in the Ajay Jadeja case, the Delhi High Court had to step in because the internal disciplinary action taken against him lacked procedural fairness. The court held that since federations perform public functions, they can be subjected to judicial review under Article 226 of the Constitution.

What these examples tell us is that internal systems, while necessary, are not sufficient. In sensitive or high-stakes disputes, you need an independent mechanism that inspires trust.

So, where do you go when internal redressal fails? One option is the courts. The other, which we shall focus on, is arbitration. But before that, let me briefly explain why going to court is often not the ideal route for resolving sports disputes in India.

Why does litigation fall short in the sports world?

Pause and think why litigation does not work.

If you are an athlete, coach, or club official in India, it might seem logical to approach the courts when internal processes fail. After all, the courts are there to enforce rights and ensure fairness, like they do for any other disputes.

And to be clear, courts have played an important role in holding sports bodies accountable. But when it comes to resolving sports disputes, especially in real time, litigation is often a poor fit.

Let me explain why.

The clock is always ticking in sport.

Unlike in most industries, timing is everything in sport. A suspension that lasts six months might mean missing a tournament you have trained for your whole life. A delayed selection decision could deny you an international cap forever. And this is exactly what sportsmen are trying to avoid.

Litigation, by its very nature, is not designed for speed. The process involves pleadings, hearings, adjournments, and appeals, all of which take so much time.

Take the case of S. Sreesanth, for example. The Indian cricketer who was banned for life by the BCCI over alleged spot-fixing. He fought a long legal battle that went through the Kerala High Court and eventually the Supreme Court. Years later, his ban was reduced, but by then, the best years of his cricketing career were already gone. And this is very unfortunate. Because if the same had been done a little earlier, his career would not have fallen apart.

In a field where age, form, and momentum matter so much, even a delay of a few months can have irreversible consequences.

Courts are not always sports-literate.

Let me say this with respect, judges are experts in law without a doubt, but not necessarily in sport. They are not trained to understand the technicalities of doping regulations, selection criteria, or the inner workings of a sports federation. As a result, decisions may be legally sound but practically disconnected from the sporting context.

In the Commonwealth Games corruption cases, for example, several procedural failures meant that many of those indicted were eventually acquitted. The legal process did not have the speed or structure to deal with time-sensitive issues of ethics, finance, and public accountability in sport.

We see this issue in Arbitration too, and institutions like AIFF as well, where the judges presiding over the cases are not necessarily experienced in sports or that particular subject of arbitration. But this is a discussion for another day. So let us move on.

Publicity can be damaging.

Court proceedings in India are public. Orders are published. Media coverage is intense. For athletes, this can be a double blow. Apart from the stress of the dispute itself, you also have to deal with public perception, reputational harm, and endless speculation. In some cases, even a favourable outcome from the court comes too late to repair the damage already done.

Contrast this with arbitration, which is usually confidential. It allows you to resolve disputes without dragging your name through newspapers and social media.

The courts themselves recognise this gap.

In several cases, Indian courts have acknowledged that litigation may not be the best forum for resolving sports-related disputes. In the case of Rajiv Dutta vs Union Of India & Ors on 15 January, 2016, the Delhi High Court observed that the dispute could have been better resolved through arbitration. But there was no arbitration clause in the underlying contract, so the court had no choice but to hear it.

That points to an important lesson: unless arbitration is clearly written into your contract, courts cannot refer you to it, even if it is the more appropriate forum.

The bigger picture

Let us be clear, the courts are essential. They are the last safeguard when all else fails. And in cases involving constitutional rights, serious misconduct, or gross injustice, they have every right to step in. But for most day-to-day sports disputes, selection issues, contractual disagreements, or disciplinary matters, litigation is just too slow, too public, and too far removed from the sporting world.

So, what is the alternative? The answer lies in arbitration. And in the next section, we shall explore how it works in the context of Indian sport, why it is well-suited to this space, and how you can actually use it.

Who actually handles sports disputes in India?

Before we get into arbitration, it is worth knowing who the key players are in the Indian sports ecosystem, because that is often where disputes begin. These bodies do not run arbitrations themselves, but their decisions can trigger them.

1. National Sports Federations (NSFs)

These are the governing bodies for each sport, like the Wrestling Federation of India (WFI), Athletics Federation of India (AFI), etc. They handle everything from selections to disciplinary actions and eligibility. Many disputes, think “why was I not picked for the national team?” or “why was I suspended?”, start here. If athletes aren’t happy with how the federation handled it, they might turn to arbitration (sometimes domestic, sometimes international, like CAS).

2. NADA (National Anti-Doping Agency)

NADA is India’s anti-doping watchdog. If an athlete tests positive for a banned substance, NADA investigates and usually refers the case to the Anti-Doping Disciplinary Panel (ADDP). The athlete can appeal to the Anti-Doping Appeal Panel (ADAP), and beyond that, to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) in Switzerland. So while NADA is not an arbitration body, its decisions often end up there.

3. SAI (Sports Authority of India)

SAI is the government’s main sports promotion body, it runs training centres, funds athletes, and implements sports schemes. It’s not involved in dispute resolution directly, but its actions (like dropping an athlete from a program or revoking funding) can lead to grievances. In some cases, athletes escalate these to sports federations, the Indian Olympic Association (IOA), or CAS if international rules are involved.

Bottom line is that these bodies are often where a sports dispute begins, but they are not the ones who resolve it through arbitration. That happens either under domestic arbitration frameworks or at CAS, depending on the contract or rules involved.

Arbitration in sports: a practical middle path

By now, you may be wondering if internal mechanisms are flawed and litigation is slow, then what realistic option remains? This is where arbitration comes in. It offers you a practical, balanced, and legally sound way to resolve disputes without stepping into a courtroom or being at the mercy of opaque internal processes.

Let us break this down.

What is arbitration, and why does it suit sports disputes?

Arbitration is a private dispute resolution process where both parties agree to submit their conflict to one or more neutral arbitrators, whose decision is binding. In India, it is governed by the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. In the sports context, this means that instead of taking your issue to a court or a federation committee, you take it to an independent panel of experts who decide the matter quickly and confidentially.

Sport, by nature, demands speed, finality, and discretion. Arbitration offers all three.

- Speed: Timelines in arbitration are more flexible and can be shortened. You do not have to wait for years.

- Confidentiality: Proceedings and outcomes are private, which is crucial for protecting reputations.

- Expertise: You can choose arbitrators with a background in sports law or the specific sport in question.

- Finality: The award is binding, and appeals are very limited. This reduces uncertainty and allows everyone to move on.

Let me give you an example.

When a contractual dispute arose between a football player and Chennaiyin FC, the matter was resolved internally by the All India Football Federation (AIFF). But if that had failed, arbitration, either institutional or ad hoc, could have been the next best step. It would have allowed both sides to present their case without entering into years of litigation.

How is arbitration different from going to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS)?

You might have heard of CAS, the international body based in Lausanne, Switzerland.

To know more about CAS, check here.

CAS is a world-renowned forum for resolving sports disputes, particularly in international matters such as doping, eligibility, or cross-border transfers. Indian athletes have approached CAS in the past; for instance, Dutee Chand challenged her disqualification over hyperandrogenism at CAS and won.

But CAS is not always the answer for domestic disputes in India. First, it can be expensive and logistically difficult to access. Second, it usually deals with international sports bodies or issues governed by global codes. If your dispute is with a local federation or relates to a domestic event or contract, you can resolve it right here in India, provided your contract includes an arbitration clause.

This is where Indian arbitration, under the 1996 Act, becomes relevant. You can either use institutional arbitration or go for ad hoc arbitration, where both parties agree on the rules and arbitrators.

Who can use arbitration in sport?

Almost anyone involved in the sports ecosystem:

- Athletes

- Coaches

- Clubs and franchises

- Agents

- Broadcasters

- Sponsors

- Sports federations

If a dispute arises from a contract or a disciplinary matter, and there is a valid arbitration clause, then arbitration becomes the preferred forum.

But is arbitration actually enforceable in India?

Yes. Arbitration awards, whether from CAS or from an Indian panel, are enforceable in India. CAS awards are treated as foreign arbitral awards under the New York Convention, to which both India and Switzerland are parties. Indian courts have upheld the enforceability of such awards in multiple cases, provided they do not violate public policy or procedural safeguards.

Domestic awards are enforced under sections 34 and 36 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. Unless a court sets aside the award (on very limited grounds), it can be enforced just like a court decree.

What this means is that arbitration is not just an advisory tool; it is a serious legal mechanism backed by enforceability.

The bottom line

Arbitration offers Indian sport a much-needed solution. It is not without its challenges, which we shall discuss later, but it gives you what courts and internal committees often cannot: timely, confidential, and expert-led justice.

In the next section, we shall go one step further and walk through how to actually use arbitration if you are facing a dispute in sport.

How to use arbitration in Indian sports disputes

So, you have a dispute. Perhaps you have been unfairly dropped from a team, your contract has been terminated without reason, or there is a financial disagreement with your club. You know that going to court could take years, and your federation’s internal panel does not inspire much confidence. What do you do next?

Here is a step-by-step guide on how to use arbitration to resolve your dispute within the Indian legal framework.

Step 1: Check the contract

The very first thing you need to do is look at the contract or agreement that governs your relationship with the other party, be it a club, a sponsor, or a federation. Does it contain an arbitration clause?

This clause should clearly state that any disputes arising out of or relating to the agreement shall be resolved through arbitration, and ideally mention:

- The seat of arbitration (e.g., New Delhi)

- The governing law (e.g., Indian law)

- The number of arbitrators (usually one or three)

- The mode of appointment of arbitrators

- The rules that will apply

If there is no arbitration clause, you cannot compel the other party to arbitrate unless both sides mutually agree to it after the dispute arises. That is rare. So, always ensure that your sports contracts have an arbitration clause from the beginning.

While parties cannot compel in place of the missing clause, federation bylaws or sports regulations (e.g., AIFF or BCCI rules) may mandate arbitration even without a specific contract clause. For example, some sports bodies incorporate arbitration in their constitutions, binding members implicitly.

Here is a simple sample clause:

“Any dispute or difference arising out of or in connection with this agreement shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration in accordance with the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The tribunal shall consist of a sole arbitrator appointed by mutual consent. The seat of arbitration shall be New Delhi, and the proceedings shall be conducted in English.”

Step 2: Exhaust internal remedies (if applicable)

Some federations require you to go through their internal grievance redressal system before you can approach arbitration. If your contract or the rules of the federation say this, you must comply otherwise, your arbitration claim could be challenged later.

That said, if the internal process is biased, unreasonably delayed, or procedurally flawed, you can argue that it has failed in substance and proceed to arbitration. Courts have accepted this argument in many contexts.

Step 3: Choose the mode of arbitration

You now have two options:

A. Institutional arbitration

This means using a formal arbitral institution, for example Delhi International Arbitration Centre (DIAC) to administer your dispute. The institution handles everything from the appointment of arbitrators to setting timelines and managing documents.

This is useful if you want structure and support, especially if you are new to arbitration.

B. Ad hoc arbitration

This is a more flexible option where both parties agree on the arbitrators, the rules, and the timelines. It is often quicker and less expensive, but only if both sides cooperate. If you do not have a pre-existing agreement or a reliable counterparty, ad hoc arbitration can become messy.

Step 4: Appoint your arbitrator(s)

If your arbitration clause mentions a sole arbitrator, then both sides must mutually agree on one. If it says three arbitrators, each side appoints one, and the two appointed arbitrators select the third.

If there is disagreement, you can approach the High Court under Section 11 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, and the court will appoint an arbitrator for you. This is straightforward, provided your arbitration clause is valid and clear.

Choose an arbitrator with sports law knowledge or someone who understands the industry. This makes a big difference in the quality and relevance of the award.

Step 5: Conduct the proceedings

Once the tribunal is formed, the process begins. The proceedings are typically written (especially for smaller disputes), but you can also request hearings.

You will file a statement of claim, the other side will file a statement of defence, and the arbitrator may ask for witness statements or documents. After hearings, the arbitrator will pass an award.

The good news is that this whole process can be completed within a few months, much faster than in court.

Step 6: Enforce the award

If the other party complies with the award, great. If not, you can enforce it as a court decree under Section 36 of the Act. The other party can only challenge the award on narrow grounds (like fraud, bias, or violation of public policy) under Section 34, and courts are generally reluctant to interfere unless the award is fundamentally flawed.

The bottom line is that arbitration is not just private justice; it carries real legal force.

A word of caution

If your contract does not include an arbitration clause or if it is poorly drafted, you may face difficulties enforcing arbitration. So, whether you are an athlete, a club manager, or a lawyer advising a client, pay attention to how these clauses are written. They are not mere boilerplate.

In the next section, we shall look at how arbitration differs from the CAS process and why domestic arbitration is often the more practical choice for resolving Indian sports disputes.

CAS: A global option, but not the only one

When we talk about arbitration in sport, the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) often comes up. Based in Lausanne, Switzerland, CAS is regarded as the global apex body for resolving sports disputes. It has dealt with everything from Olympic eligibility to doping bans, from match-fixing to governance challenges within international federations.

But here is the question I want you to ask: Is CAS always the right forum for Indian sports disputes? The answer, quite often, is no.

Let us understand why.

What is CAS, and when is it relevant?

CAS was set up in 1984 under the patronage of the International Olympic Committee (IOC). It now functions as an independent institution that handles legal disputes in sport through arbitration and mediation. It applies its own rules and hears cases from around the world.

You might go to CAS if:

- You are challenging a doping sanction under the World Anti-Doping Code.

- You are contesting a decision by an international federation like FIFA, the IAAF, or the ITTF.

- You are appealing a ruling made by the internal dispute body of an international event or the Olympic Committee.

Indian athletes have taken matters to CAS before. A well-known example is Dutee Chand’s challenge to the IAAF’s hyperandrogenism policy, which led to a suspension of the rules and opened the door for future challenges to sex-based eligibility criteria in sport.

Another example is doping cases where the National Anti-Doping Appeal Panel may have passed an order, and the athlete then files a further appeal at CAS.

In such cases, CAS has jurisdiction because the rules of the relevant international federation or code explicitly allow for it.

Why CAS is not always the best or necessary option

Despite its prestige, CAS is not mandatory for most disputes in Indian sport. In fact, it may not even be available unless the dispute relates to an international federation or is governed by a contract that contains a CAS clause.

Here are some practical limitations:

- Costs and logistics

Taking a matter to CAS can be expensive. Filing fees, travel costs, legal representation, and hearing logistics can be significant barriers, especially for young athletes, small clubs, or domestic associations.

- Not suitable for domestic disputes

Most selection issues, player-club disputes, and federation governance matters are domestic. CAS does not deal with these unless there is a link to an international sporting body or code. For example, a cricketer’s dispute with the BCCI or a footballer’s grievance with an ISL team is better suited for Indian arbitration.

- CAS is not a forum of first instance

CAS usually acts as an appellate forum. That means you must first exhaust internal remedies or appeal procedures in your federation or under the applicable sports code before going to CAS.

So what should you do instead?

If your dispute is entirely within India, and especially if it involves:

- Domestic federations (e.g., AIFF, WFI, BAI)

- Contracts under Indian law

- Issues of selection, fees, conduct, or representation

… then a domestic arbitration under the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 is more efficient, more affordable, and legally sound.

You still get all the advantages of arbitration speed, confidentiality, and enforceability, but without the hurdles of going abroad or navigating international codes.

Think of CAS as the Supreme Court of the sports world. It is powerful, it is respected, and it serves a crucial role. But like all apex bodies, it is not the place to take every case. For many disputes, the best solution lies closer to home.

In the next section, we shall talk about how to draft good arbitration clauses in sports contracts and why doing so early can save you from confusion and delays later.

Drafting tips: clauses and contracts

By now, we know that arbitration is only possible if there is an agreement between the parties to resolve disputes that way. This agreement usually comes in the form of an arbitration clause written into a contract. If you are an athlete, club, sponsor, agent, or legal adviser, this clause is not something you should overlook or treat as boilerplate. It is the bridge between a dispute and a solution.

So let us look at how to draft a good arbitration clause, particularly for sports contracts in India.

What makes a good arbitration clause?

A well-drafted arbitration clause should answer six basic questions:

- What types of disputes are covered?

- What law will govern the arbitration?

- Where will the seat and venue of the arbitration be?

- Who will appoint the arbitrator(s), and how?

- How many arbitrators will there be?

- What rules will govern the process?

If any of these are missing or vague, you risk confusion or delay when a dispute arises.

Sample clause for a player–club agreement

“Any dispute, controversy, or claim arising out of or in connection with this Agreement, including any question regarding its existence, validity, interpretation, or termination, shall be referred to and finally resolved by arbitration in accordance with the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996. The tribunal shall consist of a sole arbitrator to be appointed by mutual agreement between the Parties. If the Parties fail to agree on the arbitrator within 14 days of the notice of arbitration, the arbitrator shall be appointed by the Delhi High Court under Section 11 of the Act. The seat and venue of arbitration shall be New Delhi. The arbitration proceedings shall be conducted in English, and the award shall be final and binding on both Parties.”

Customising clauses for different contracts

For athlete–sponsor agreements

“Disputes relating to payments, usage of likeness, or obligations under this endorsement agreement shall be resolved by arbitration in Mumbai, with a sole arbitrator appointed by the Indian Council of Arbitration. The award shall be final, and no appeal shall lie except under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996.”

For coach–club agreements

“Any employment-related dispute shall be subject to arbitration in accordance with the rules of the ___ Sports Dispute Resolution Centre. A panel of three arbitrators shall be appointed, one by each party and the third by ___.”

For agent–player contracts

“Any dispute under this contract, including claims for commission, breach of confidentiality, or exclusivity, shall be arbitrated in Chennai under ad hoc rules. The seat shall be Chennai, and the governing law shall be Indian law.”

Common mistakes to avoid

- Leaving the clause too open-ended: Saying “disputes shall be settled amicably” is not an arbitration clause. It is wishful thinking.

- Not specifying a seat: This creates confusion over jurisdiction and court powers.

- Failing to name the law: If the governing law is unclear, enforcement becomes tricky.

- Not considering neutrality: Always ensure that the arbitrator or seat is neutral, especially in high-stakes or cross-party contracts.

Why does this matter so much in sport?

Sports careers are short. When a dispute arises, no one wants to waste months deciding where and how to resolve it. A good clause makes all the difference. It allows you to bypass the uncertainty, select a qualified arbitrator, and move towards resolution with confidence and speed.

In the final sections, we shall step back and look at the bigger picture of what arbitration offers to Indian sport, and what needs to change for it to become the default, rather than the exception.

Conclusion

Disputes are inevitable in sport. Whether it is a young athlete left out of a tournament, a club accused of breaching a contract, or a federation caught in governance controversy, conflict is part of the competitive ecosystem. The real question is not whether disputes will arise, but how we choose to resolve them.

In India, we have long relied on internal federation processes and the court system. But as we have seen, internal mechanisms often lack independence, while litigation is too slow and too public for the fast-moving, reputation-sensitive world of sport. Arbitration, by contrast, offers a practical, efficient, and confidential solution, one that respects both the letter of the law and the spirit of the game.

This is not to say arbitration is perfect. Access remains uneven. Awareness is limited. Many contracts still do not carry enforceable arbitration clauses. And we do not yet have a robust domestic sports arbitration institution with the same standing as the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS). But the foundation exists. The legal framework is in place. The courts have expressed support for arbitration in principle. What remains is the cultural shift to treat arbitration not as an alternative, but as the default method of resolving sports disputes.

If you are an athlete, administrator, lawyer, or policymaker, the message is simple. Start early. Write clear arbitration clauses. Educate stakeholders. Push federations to adopt standard procedures. Choose experts to decide sporting conflicts. And above all, remember that the best way to protect sport is to resolve its disputes fairly, swiftly, and quietly so that the real action can stay where it belongs: on the field.

Frequently asked questions (FAQs)

- Can an athlete force a national sports federation into arbitration?

Not automatically. Arbitration requires both parties to agree to it, usually through an arbitration clause in a contract, athlete agreement, or federation rules. If there is no such agreement, the athlete may need to go through internal grievance redressal mechanisms or approach the courts.

- Is arbitration available for selection disputes, like being left out of a team?

It depends. Many selection disputes fall under the “sovereign functions” or discretion of federations and may not always be arbitrable. But if there is a violation of agreed-upon procedures or discriminatory conduct, it can open the door to arbitration or judicial review.

- Can Indian athletes directly approach the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS)?

Yes, but only in limited scenarios, usually when the rules of a federation (national or international) or a contract allow it. CAS typically handles appeals from final decisions of international federations or national-level bodies where CAS jurisdiction is explicitly accepted.

- What if the athlete cannot afford international arbitration at CAS?

Costs can be a barrier. However, CAS has a legal aid fund for athletes with limited means, especially in anti-doping cases. Some Indian sports law firms or NGOs also offer pro bono assistance in deserving cases.

- Does Indian law recognise awards passed by CAS?

Yes. CAS awards are treated as foreign awards under the New York Convention, and can be enforced in India under Part II of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, provided they meet certain conditions.

- Can a dispute involving both doping and selection be arbitrated together?

Not usually. Doping cases have a clear process through NADA and CAS. Selection disputes follow a different track, often internal to federations. If both issues overlap, they may need to be resolved separately or sequentially, unless the arbitration agreement allows consolidation.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications