Part one of the SHA series explores the critical foundation of post-investment control mechanisms. Learn to craft balanced board composition and decision-making frameworks that protect both founders and investors following seed funding.

Table of Contents

Introduction

“But the term sheet already covers everything. Why do we need another document?“, Rahul asked, leaning back in his chair with a mixture of exhaustion and confusion.

Priya nodded in agreement, “We have already negotiated all the important terms. Can’t we just sign something quick and get back to building our product?“.

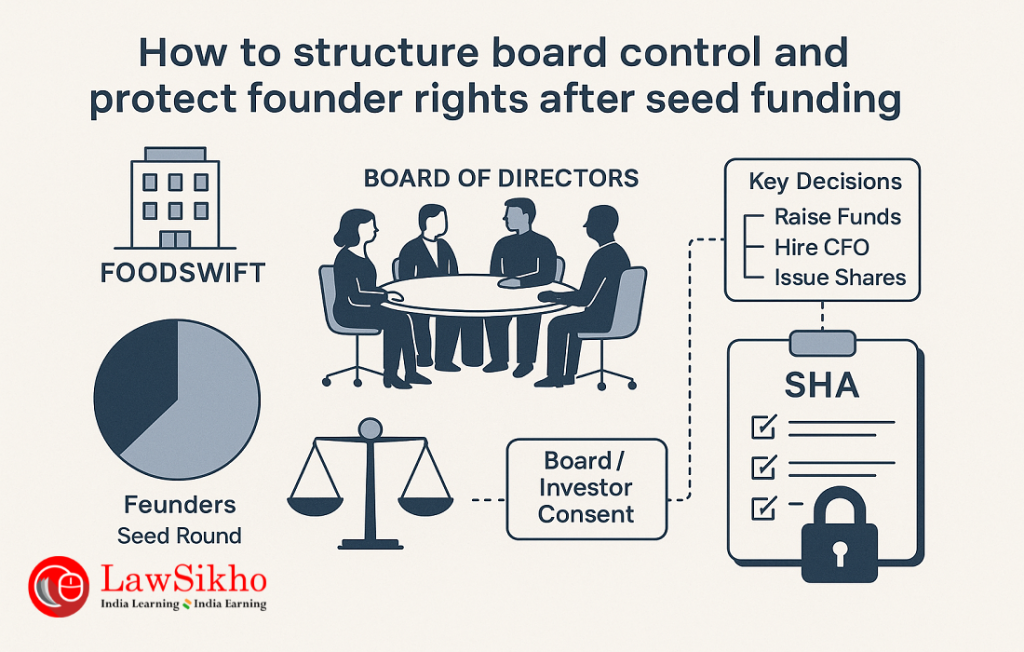

I smiled at FoodSwift’s founders. After months of preparation and negotiation, they had finally closed their Seed Round—₹1 crore for 13.04% equity from Altitude Ventures. The champagne bottles from yesterday’s celebration were still in the recycling bin. But their fundraising journey was not over yet.

“The term sheet is just the promise of what’s to come,” I explained. “Think of it as the engagement. Now we need to draft the marriage contract—the Shareholders’ Agreement.“

If you have been following our previous articles (Term Sheets at Seed Stage: How to Negotiate and Advise), you will recall how we prepared FoodSwift’s legal foundation for investment and navigated the term sheet negotiation process. Now comes the crucial next step, which is translating those high-level terms into a comprehensive Shareholders’ Agreement (SHA).

Why is the SHA so important?

While the term sheet outlines the headline terms, the SHA creates the actual legal framework that will govern the relationship between founders and investors for years to come. It is the rulebook everyone must play by.

“Term sheets typically run 3-5 pages. SHAs run 15-20 pages,” I told Rahul and Priya. “The difference is not just length but precision and enforceability.“

The SHA is not the same as your Articles of Association (AoA), though they work together.

The AoA is a public document filed with the Registrar of Companies (RoC) that establishes governance rules.

The SHA is a private contract among shareholders that can include more detailed, confidential provisions that may not be appropriate for public filing.

For FoodSwift, with fresh capital and a new investor on board, the SHA would establish:

- Who controls what decisions

- How the board functions

- What rights do different shareholders have

- What happens if someone wants to sell shares

- How disputes get resolved

As a young lawyer drafting your first SHA, you might think that you are just documenting an investment. But that is not the reality, you are actually creating a governance blueprint for what could become the next unicorn.

So, getting SHA right means understanding both legal nuances and business realities.

What will be covered in Part 1?

In this first article of our SHA series, I will focus on the essential control and decision-making framework that forms the backbone of any shareholders’ agreement:

- Definitions & Interpretation – Understanding the importance of precise terminology that will be used throughout the SHA

- Shareholding & Capital Structure – Clearly documenting who owns what and establishing the company’s equity framework

- Board Composition & Governance Rights – Determining who gets board seats and how the board functions

- Voting Rights & Reserved Matters – Identifying which decisions require special approvals and how to structure these protections

Each of these sections represents a critical building block in creating a balanced SHA that protects both founders and investors. I will share actual clauses from FoodSwift’s agreement, practical drafting tips, and common pitfalls to avoid.

Let us begin with definitions and interpretation—the linguistic foundation upon which everything else is built.

Definitions & interpretation

Let me start with a confession that might surprise some of you: the definitions section is my favorite part of drafting a shareholders’ agreement. Yes, you read that right.

When I shared this with Rahul and Priya during our first SHA drafting session, they looked at me like I had just claimed that tax audits were my idea of a fun weekend.

“Definitions? Really?” Rahul laughed. “That is the part most people skip right over.“

“Exactly,” I replied. “And that is precisely why it is where sophisticated investors and lawyers often embed provisions that quietly shape the entire agreement.“

The truth is, definitions are not just a reference section—they are the linguistic infrastructure that determines how rights and obligations function throughout the document. They affect when investor protections trigger, how control mechanisms operate, and how economic outcomes are calculated.

After explaining this to FoodSwift’s founders, we dove into the definitions with a new appreciation for their strategic importance.

The strategic importance of definitions

Definitions perform several crucial functions in your SHA:

- Precision – They eliminate ambiguity by giving specific meaning to key terms.

- Efficiency – They allow complex concepts to be expressed concisely throughout the document.

- Scope control – They determine when rights and obligations are triggered.

- Consistency – They ensure terms are interpreted uniformly throughout the agreement.

As one of my mentors once told me, “The definitions section is where sophisticated lawyers quietly win negotiations while everyone else focuses on the operative clauses.“

Essential definitions for seed-stage SHAs

Based on FoodSwift’s SHA and dozens of others I have drafted, here is a comprehensive list of definitions that matter most in seed-stage agreements:

1. Structural and identifying definitions

- “Affiliate” – Entities that control, are controlled by, or are under common control with a party.

- “Board” – The board of directors of the Company as constituted from time to time.

- “Business” – The specific business activities the company is authorised to conduct.

- “Company” – The entity that is the subject of the agreement (e.g., FoodSwift Private Limited).

- “Effective Date” – The date on which the agreement becomes binding.

- “Founders” – The specific individuals recognised as founders with specific rights and obligations.

- “Investor” – The entity or individual making the investment.

2. Equity and economic definitions

- “Equity Securities” – All classes of shares, options, warrants, and other instruments convertible into shares.

- “Fully Diluted Share Capital” – Total issued shares plus all potential shares from convertible securities and option pools.

- “Liquidity Event” – Circumstances that trigger liquidation preferences (e.g., acquisition, merger, sale of assets).

- “Liquidation Preference” – The preferential distribution rights of preferred shareholders upon a Liquidity Event.

- “Preference Shares” – Shares carrying preferential rights as defined in the Articles.

- “Equity Shares” – Ordinary voting shares without special rights or preferences.

- “Pre-Money Valuation” – The agreed valuation of the Company prior to the investment.

- “Post-Money Valuation” – The Pre-Money Valuation plus the amount of the investment.

- “Subscription Amount” – The total funds being invested.

3. Control and governance definitions

- “Articles of Association” – The Company’s articles as amended from time to time.

- “Control” – The power to direct management and policies through share ownership, voting rights, or contract.

- “Deed of Adherence” – The document new shareholders must sign to be bound by the SHA.

- “Founder Director” – A director nominated by the Founders.

- “Investor Director” – A director nominated by the Investor.

- “Observer” – A non-voting representative with the right to attend board meetings.

- “Reserved Matters” – Decisions requiring special approval as listed in the agreement.

- “Shareholder Reserved Matters” – Reserved matters requiring shareholder (not just board) approval.

4. Transfer and exit definitions

- “Change of Control” – A transaction resulting in a change of majority ownership or board control.

- “Drag-Along Right” – The right to force other shareholders to join in a sale.

- “Exit” – Defined scenarios where investors realize their investment (e.g., IPO, acquisition).

- “Fair Market Value” – The methodology for determining share value in specific contexts.

- “IPO” – Specific requirements for what constitutes a qualifying initial public offering.

- “Permitted Transfers” – Share transfers that are exempted from transfer restrictions.

- “Right of First Refusal” – The right to purchase shares before they’re offered to third parties.

- “Right of First Offer” – The right to receive the first offer of shares before they’re marketed to others.

- “Tag-Along Right” – The right to participate proportionately in a sale of shares by other shareholders.

5. Protection and preference definitions

- “Anti-Dilution Protection” – Mechanisms protecting investors from dilution in down rounds.

- “Conversion Price” – The price at which preferred shares convert to equity shares.

- “ESOP” – The employee stock option plan and related share reserve.

- “Information Rights” – Rights to receive specific company information at defined intervals.

- “Participating Preference” – Whether preference shareholders participate in the remaining proceeds beyond their preference amount.

- “Pro Rata Right” – The right to maintain percentage ownership in future financing rounds.

- “Qualified Financing” – A financing meeting with specific size or valuation thresholds.

Sample definitions from FoodSwift’s SHA

Let me share a few actual definitions from FoodSwift’s SHA to demonstrate how these are crafted in practice:

“Affiliate” means, with respect to any Person, any other Person that directly or indirectly Controls, is Controlled by, or is under common Control with, such Person. For purposes of this definition, “Control” (including, with correlative meanings, the terms “Controlled by” and “under common Control with”) means the possession, directly or indirectly, of the power to direct or cause the direction of the management or policies of a Person, whether through ownership of more than fifty percent (50%) of voting securities, by contract, or otherwise, as defined under Section 2(27) of the Companies Act, 2013.

“Fully Diluted Share Capital” means the total issued and paid-up Equity Share capital of the Company, plus all potential Equity Shares issuable upon conversion of outstanding convertible securities, options, warrants, and other instruments (whether or not currently convertible), including all shares reserved for issuance under the ESOP, whether granted or unallocated.

“Liquidity Event” means:

(i) a merger, consolidation, or other transaction where the shareholders of the Company immediately prior to the transaction hold less than fifty percent (50%) of the voting power of the surviving entity;

(ii) the sale or transfer of all or substantially all of the Company’s assets, where ‘substantially all’ means assets representing at least 75% of the Company’s total asset value;

(iii) the liquidation, dissolution, or winding up of the Company under applicable law. For clarity, the grant of licenses to intellectual property, whether exclusive or non-exclusive, shall not constitute a Liquidity Event unless it results in the transfer of substantially all of the Company’s intellectual property rights.

Interpretation clauses

Beyond definitions themselves, every SHA should include interpretation clauses that establish reading rules for the entire document. Here is what we included for FoodSwift:

“Interpretation. In this Agreement, unless the context requires otherwise:

(a) References to a person include any individual, company, partnership, joint venture, firm, association, trust, governmental authority, or other entity;

(b) The singular includes the plural and vice versa;

(c) References to a gender include all genders;

(d) “Including” means “including without limitation”;

(e) Headings are for convenience only and do not affect interpretation;

(f) References to “Clauses,” “Sections,” or “Schedules” are to the clauses, sections, or schedules of this Agreement;

(g) References to laws include any amendment, modification, or re-enactment thereof;

(h) The Schedules and Recitals form an integral part of this Agreement.”

Drafting tips for definitions

From experience, here are my key recommendations for drafting effective definitions:

- Be comprehensive but precise – Include all terms that have specific meanings, but avoid unnecessary definitions that could create confusion.

- Match commercial understanding – Ensure defined terms reflect what the parties actually understand and intend, not just standard legal language.

- Be consistent across documents – Align definitions with those in the Articles of Association and any ancillary agreements.

- Future-proof where possible – Draft definitions that can accommodate future rounds without requiring complete redefinition.

- Consider your jurisdiction – Incorporate references to relevant statutory provisions in Indian law where applicable.

- Use cross-references carefully – Avoid circular definitions or excessive nesting that makes terms difficult to interpret.

Lawyer’s corner: When reviewing draft SHAs prepared by opposing counsel, I always check the definitions first. That is where sophisticated investors often embed provisions that subtly expand their rights or restrict founder flexibility. For instance, an overly broad definition of “Liquidation Event” can trigger preferences in scenarios the founders never anticipated. Do not assume definitions are standardized or inconsequential—they’re often where the real negotiation happens.

Common pitfalls in definition drafting

As I review SHAs drafted by junior lawyers, these are the most common definition-related mistakes I encounter:

- Inconsistent capitalisation – Defined terms must be consistently capitalized throughout the document to signal when the defined meaning applies.

- Circular definitions – Terms defined by reference to themselves or creating definitional loops.

- Overbroad business descriptions – Defining “Business” too broadly can inadvertently restrict legitimate company activities or trigger unintended investor approval rights.

- Inconsistent terms across documents – Different definitions in the SHA and Articles create interpretation conflicts.

- Undefined substantive terms – Leaving key concepts undefined that directly impact rights or obligations.

- Including substantive obligations within definitions – Substantive obligations should be in operative clauses, not hidden in definitions.

While definitions may seem tedious to draft and review, they form the critical foundation for every other provision in your SHA. Get them right, and you will create clarity and certainty; get them wrong, and you will plant seeds of future disputes.

With properly defined terms in place, we now have the complete linguistic framework for drafting the operational provisions of the SHA.

Shareholding & capital structure: Who owns what

When I sat down with FoodSwift’s founders after their successful fundraise, their first question was not about complex legal clauses—it was much simpler.

“So exactly how much of the company does everyone own now?” Rahul asked, pen hovering over his notebook.

This straightforward question lies at the heart of any SHA. Before diving into governance rights and control mechanisms, your agreement must clearly establish the company’s capital structure and shareholding pattern.

For FoodSwift, this meant documenting their post-investment cap table: –

- Rahul and Priya each owned 43.48% of the issued capital (39.13% on a fully diluted basis), down from 50% pre-investment

- Altitude Ventures owned 13.04% of the issued capital (11.74% on a fully diluted basis) after investing ₹1 crore

- A 10% ESOP pool was created within the authorized but unissued capital

But properly documenting shareholding involves much more than just these percentages.

Key elements of the shareholding section

A comprehensive shareholding section in your SHA should address:

- Authorised vs. Issued Capital – Specify both the total authorised share capital (the maximum shares the company can issue) and the currently issued share capital. For FoodSwift, we documented:

- Authorised: ₹10 lakhs divided into 100,000 equity shares of ₹10 each

- Issued: ₹7.67 lakhs divided into 76,700 equity shares of ₹10 each

- Share Classes – Detail any different classes of shares and their respective rights. Even if you currently have only ordinary equity shares (as FoodSwift did), including this framework allows for future flexibility.

- Shareholding Table – Include a detailed cap table showing:

- Names of all shareholders

- Number of shares held

- Percentage of ownership

- Class of shares

- Share certificate numbers (if issued)

- Future Equity Pools – Document any reserved employee stock option pools. For FoodSwift, we specified a 10% ESOP pool that had been created but not yet allocated.

Here is a sample clause from FoodSwift’s SHA:

“The Company’s capital structure immediately following the Closing shall be as set forth in Schedule I. The Company and the Founders represent that there are no other shares, options, warrants, conversion rights, or other instruments that could require the Company to issue any additional Equity Securities, except as specifically disclosed in Schedule I.”

Visual representation matters

I have found that including a visual cap table as a schedule to the SHA helps all parties understand the ownership structure at a glance. Here is a simplified version of what we included for FoodSwift:

FoodSwift Pvt Ltd: post-investment cap table

| Shareholder | Number of shares | Percentage (Issued) | Percentage (Fully Diluted) | Share type |

| Rahul Sharma | 33,348 | 43.48% | 39.13% | Equity |

| Priya Venkatesh | 33,348 | 43.48% | 39.13% | Equity |

| Altitude Ventures | 10,004 | 13.04% | 11.74% | Equity |

| TOTAL (Issued) | 76,700 | 100% | 90% | |

| ESOP Pool (Unallocated) | 7,670 | 0% (unissued) | 10% | Reserved |

| Fully Diluted Total | 84,370 | 100% |

Lawyer’s Corner: – The ESOP pool of 7670 shares is reserved within the authorised share capital but not yet issued, representing 10% of the fully diluted share capital. The issued share capital totals 76,700 shares, with the percentage shown above reflecting only issued shares unless otherwise stated.

Practical drafting tips

- Be precise about fully-diluted calculations – Specify exactly what “fully-diluted” means in your context. Does it include only issued shares, or also all reserved ESOP shares and convertible instruments?

- Address future issuances – Include language about how new share issuances will be calculated and offered. This becomes crucial for protecting against dilution.

- Reconcile with statutory registers – Ensure the shareholding information matches what’s in the company’s register of members and what is been filed with the Registrar of Companies.

- Consider Indian legal requirements – Under Section 56 of the Companies Act, share transfers must be properly documented with transfer forms and board approvals. Reference these requirements in your SHA.

With clarity established on who owns what, we can now move to the next critical question: who controls what?

This brings us to board composition and governance rights.

Board composition & governance rights: the control center

“We built this company from scratch. Why should someone who just joined get a say in how we run it?“

Priya’s question during our SHA drafting session was a natural reaction to seeing Altitude Ventures’ request for a board seat. The investor was putting in ₹1 crore for 13.04% equity, but would now have one-third of the board votes.

This tension between ownership percentage and governance influence is at the heart of every SHA negotiation.

I explained by saying, “Think of it this way, Investors are not just buying shares. They are buying the right to help steer the ship. Their board seat is not about controlling day-to-day decisions, it is about having visibility and input on major strategic choices.“

After some discussion, Priya nodded. “I get it. But how do we make sure we do not lose control of our own company?“

This is precisely where careful board composition clauses come into play.

Key elements of board composition clauses

For seed-stage startups like FoodSwift, board composition typically follows a simple formula. Founders maintain majority control, while investors gain meaningful representation. Here is how I structured it:

1. Board size and composition

FoodSwift’s board composition clause stated:

“The Board shall consist of a maximum of three (3) directors, of which:

(a) Two (2) directors shall be nominated by the Founders (the “Founder Directors”); and

(b) One (1) director shall be nominated by Altitude Ventures (the “Investor Director”).”

This 2:1 structure preserved founder control while giving the investor appropriate representation for their capital contribution.

2. Appointment and removal rights

The SHA must clearly establish who can appoint and remove directors:

“Each Shareholder with the right to nominate a Director shall have the right to remove any Director so nominated and to nominate another in their place. The Shareholders shall vote their shares to ensure the election, appointment, or removal of Directors in accordance with this clause.”

This language prevents shareholders from blocking each other’s legitimate board appointments.

3. Quorum requirements

Quorum provisions determine when board meetings can validly proceed:

“The quorum for Board meetings shall be two (2) Directors, including at least one (1) Founder Director and the Investor Director (or their respective alternates appointed under Section 161 of the Companies Act, 2013). If the Investor Director or their alternate is unavailable despite reasonable notice, the quorum may consist of two (2) Founder Directors, provided the Investor Director is given written notice of all decisions made at such meeting within 48 hours.”

This balanced approach ensures investors cannot be shut out of meetings, while also preventing them from holding valid meetings without founder participation. The provision for alternates and flexibility in exceptional circumstances prevents operational paralysis due to the unavailability of directors.

Additionally, each nominating shareholder may appoint an alternate director under section 161 to act in the absence of their nominated director, subject to compliance with the Companies Act, 2013.

4. Observer rights

Some investors may accept observer rights instead of full board seats at the seed stage. While Altitude wanted a full seat at FoodSwift, here is sample language for observer rights:

“Altitude Ventures shall have the right to appoint one (1) observer to attend all Board meetings. The observer shall receive all notices and materials provided to Board members but shall have no voting rights.”

Observer rights offer visibility without control—a good compromise for smaller investors.

Navigating the director appointment under the Companies Act 2013

When drafting these provisions, be mindful of section 152 of the Companies Act, which governs director appointments. The Act requires:

- Directors may be appointed by shareholders at general meetings or by the board as additional directors or to fill casual vacancies under section 161, subject to confirmation at the next general meeting

- Directors must obtain Director Identification Numbers (DINs) under section 153

- Consent to act as directors must be filed with the Registrar of Companies under section 152(5)

Unlike public companies, private companies like FoodSwift are exempt from the requirement under section 152(6)(b) that at least two-thirds of directors must be appointed by shareholders and subject to retirement by rotation. Your SHA board provisions must align with these requirements.

For FoodSwift, we included this clause:

“The Shareholders agree to exercise their voting rights to implement the board composition provisions of this Agreement, including by passing necessary shareholder resolutions for the appointment, removal, or replacement of directors in accordance with the Companies Act, 2013. Directors may also be appointed by the board as additional directors or to fill casual vacancies in accordance with Section 161, subject to confirmation at the next general meeting.”

Strategic considerations when drafting board provisions

Based on my experience with dozens of seed-stage SHAs, here are the critical points to consider:

1. Balance vs. Control

For FoodSwift, we maintained founder control (2:1 board ratio) despite the investor pushing for equal representation. This was appropriate given the early stage and relatively small investment amount.

As a rule of thumb:

- Seed round: Founders typically maintain board control

- Series A: The Board often becomes more balanced

- Series B and beyond: Investors may gain equal or majority control

2. Deadlock resolution

Even with founder control, deadlocks can occur on reserved matters that require investor approval. Consider including deadlock resolution mechanisms:

“In the event of a deadlock on any Board decision requiring Investor Director approval that remains unresolved for fifteen (15) days, the matter shall be referred to the CEO of Altitude Ventures and the Founders for resolution in good faith within thirty (30) days. If no resolution is reached, the matter shall be escalated to a neutral mediator agreed upon by the parties, whose decision shall be non-binding but advisory, unless otherwise agreed. The Company shall not proceed with the disputed action until the deadlock is resolved, except for time-sensitive matters requiring compliance with applicable law.”

This provides a clear escalation path and prevents perpetual stalemates that could paralyse company operations.

3. Board committees

For more complex startups, consider provisions for board committees:

“The Board may establish committees as it deems appropriate. Any committee with authority over Reserved Matters shall include the Investor Director as a member.”

4. Meeting frequency and notice

Specify operational details to prevent procedural disputes:

“The Board shall meet at least once every quarter. Notice of at least seven (7) days shall be provided for all Board meetings, including agenda and relevant materials, unless waived by all Directors.”

Lawyer’s Corner: Founders often resist giving board seats to early investors, viewing it as surrendering control. I help them understand that board seats are not just about control—they are about adding strategic value. In FoodSwift’s case, their investor brought food industry expertise that proved invaluable. Structure board rights to leverage this expertise while protecting founder autonomy on day-to-day decisions.

Common pitfalls in board provisions

I am telling this from my experience, you must watch out for these frequent issues in board composition clauses:

- Inflexible board sizes – Specifying exact numbers rather than minimums/maximums can create problems when new investors join.

- Quorum requirements that enable stonewalling – If any single director can prevent quorum, they can effectively paralyze the board.

- Failing to address alternate directors – Include provisions for alternates when directors cannot attend.

- Overlooking written resolutions – Specify whether and how board decisions can be made by written consent without meetings.

With board composition established, the next critical question is: which decisions require special approval? This brings us to voting rights and reserved matters—the mechanisms that determine who can make which decisions.

Voting rights & reserved matters: the decision-making framework

“Wait, are you saying we need their permission to hire a senior engineer? That cannot be right.” Rahul looked up from the draft SHA with alarm.

I quickly scanned the section he was pointing to. “Good catch. That is too restrictive for a seed-stage company. Let us revise that reserved matter to only apply for C-level executives, not all senior hires.“

This exchange highlights one of the most delicate balancing acts in any SHA. The legal advisor needs to determine which decisions require special approvals and which remain within the founders’ discretion. Get this wrong, and you will either hamstring the company’s operations or leave investors without meaningful protections.

Understanding the dual control structure

Most SHAs implement a dual-layered control structure:

- General voting rights – Determine how routine matters are decided (usually by simple majority).

- Reserved Matters – Specify important decisions that require special approvals (either from the investor director or from the investor directly as a shareholder).

Let us understand both elements.

General voting rights

For most ordinary business decisions, companies follow standard voting procedures:

- Board decisions – Usually require a simple majority vote of directors present at a validly constituted meeting.

- Shareholder decisions – Typically follow statutory requirements: simple majority for ordinary resolutions and 75% majority for special resolutions under the Companies Act.

For FoodSwift, we drafted this straightforward clause for board voting:

“Except for Reserved Matters, all decisions of the Board shall be made by simple majority of the Directors present and voting. Each Director shall have one vote.”

For shareholder voting, we aligned with statutory requirements while clarifying how parties would exercise their votes:

“Except for Shareholder Reserved Matters, the Shareholders shall vote their Shares at any general meeting of the Company in accordance with the provisions of the Act, with each Share carrying one vote.”

These provisions establish the baseline voting framework. The real negotiation centers around the exceptions—the reserved matters.

Reserved matters

“Think of reserved matters as the investor’s safety net,” I explained to Rahul and Priya. “They are not about controlling your day-to-day decisions but about preventing fundamental changes that could harm their investment.“

Reserved matters typically fall into two categories:

- Board reserved matters – Decisions requiring approval of the investor director at the board level.

- Shareholder reserved matters – More fundamental decisions requiring the investor’s approval as a shareholder, regardless of their percentage ownership.

For FoodSwift, after careful negotiation, we structured their reserved matters as follows:

Board reserved matters (requiring Investor Director approval):

“The following decisions shall require the affirmative vote of the Investor Director in addition to any other approval required by law:

(a) Annual business plan and budget, and any material deviations therefrom;

(b) Appointment or removal of C-level executives;

(c) Any capital expenditure or debt exceeding ₹25 lakhs not included in the approved budget;

(d) Entering into, modifying, or terminating any contract with a value exceeding ₹50 lakhs annually;

(e) Any related party transactions;

(f) Changes to accounting methods or policies; and

(g) Initiation or settlement of any litigation exceeding ₹10 lakhs in value.”

Shareholder Reserved Matters (requiring investor approval as a shareholder):

“The Company shall not take any of the following actions without the prior written consent of Altitude Ventures, regardless of any other shareholder approval:

(a) Amendment to the Articles of Association or Memorandum of Association;

(b) Changes to the rights, preferences, or privileges of any share class;

(c) Issuance of new securities or changes to the capital structure;

(d) Any merger, acquisition, or sale of substantial assets;

(e) Changes to the size or composition of the Board;

(f) Dissolution, liquidation, or filing for bankruptcy; and

(g) Any transaction that would result in a change of control.”

Strategic considerations in drafting reserved matters

The reserved matters section requires careful calibration. Too many reserved matters can paralyse the company; too few can leave investors exposed.

Here are key strategies I have developed over the years of negotiating seed-stage SHAs:

1. Thresholds matter

Notice that FoodSwift’s reserved matters include specific monetary thresholds (₹25 lakhs for unbudgeted expenditures, ₹50 lakhs for contracts). These thresholds should be:

- High enough to allow normal operations without constant approvals

- Low enough to catch truly significant decisions

- Scaled to the company’s size and stage

2. Duration considerations

Some reserved matters include implicit time limitations:

“For a period of three (3) years from Closing, any changes to the primary business focus of the Company shall require Investor approval.”

This allows restrictions to organically expire as the company matures.

3. Exceptions for operational flexibility

Include carve-outs for time-sensitive or routine matters:

“Notwithstanding the above, the Company may exceed budgeted expenses by up to 10% without Investor Director approval provided such excess is reported at the next Board meeting.”

4. Cascading approval levels

For some matters, consider tiered approval requirements:

“For unbudgeted expenditures: (i) up to ₹10 lakhs requires CEO approval; (ii) ₹10-25 lakhs requires Board majority approval; and (iii) above ₹25 lakhs requires Investor Director approval.”

Common pitfalls in reserved matter drafting

In my years advising startups, I have seen these recurring mistakes in reserved matter provisions:

- Overly broad categories – Avoid undefined terms like “material contracts” without specifying what “material” means.

- Reserved matter overload – More than 15-20 reserved matters often signal overreaching by investors for a seed round.

- Circular approval requirements – Do not create approval loops where A needs B’s approval, which needs C’s approval, which needs A’s approval.

- Missing mechanics – Specify how approvals are requested and the timing for responses:

“The Company shall request approval for Reserved Matters in writing, and Investors shall respond within five (5) business days, failing which approval shall be deemed granted.”

Lawyer’s Corner: Reserved matters are often presented as a standard list, but they should be customized to the specific context. At FoodSwift, we negotiated removing technology development decisions from reserved matters since Priya’s technical expertise far exceeded the investor. In exchange, we accepted stricter financial approval thresholds. This balanced approach protected the investor’s financial interests while preserving the founders’ operational autonomy, where they excelled.

Anchoring reserved matters as per the Companies Act

Under Indian company law, certain decisions already require special approval regardless of your SHA:

- Section 179 of the Companies Act outlines the general powers of the board, which may be subject to shareholder approval for certain matters under the Act or AoA.

- Section 180 requires special resolutions for specific actions, such as selling substantial assets or borrowing beyond prescribed limits.

- Sections 185 and 186 regulate loans to directors and company investments, respectively, and may overlap with reserved matters involving financial transactions.

Your SHA’s reserved matters should acknowledge these statutory requirements and build upon them rather than conflict with them.

I included this acknowledgement in FoodSwift’s SHA:

“The Reserved Matters specified herein are contractual obligations among the shareholders and supplement, but do not override, matters requiring board or shareholder approval under the Companies Act, 2013, such as special resolutions under Section 180 or board powers under Section 179. The parties agree to exercise their voting rights to implement these provisions in compliance with applicable law.”

The negotiation strategy: less is more

When negotiating reserved matters, I advise founders to push for a focused list that protects genuine investor concerns without micromanaging. For investors, I emphasize the importance of meaningful protections without operationally constraining the company.

I told Altitude’s investment manager during negotiations that “The best reserved matters list is the shortest one that still protects your core interests. Too many restrictions will only slow down the company you have invested in.“

They ultimately agreed to reduce their initial list of 23 reserved matters down to 14 focused items, a win for everyone involved.

With these key control provisions established, FoodSwift had a clear framework for who could make which decisions—the essential governance foundation for their growth journey.

Closing Part 1

I have now established the critical foundation of control and decision-making in FoodSwift’s Shareholders’ Agreement.

From precise definitions to balanced board composition to carefully calibrated reserved matters, these provisions create the governance blueprint that will guide FoodSwift’s growth journey.

In Part 2, I will build on this foundation by exploring how to maintain alignment through lock-in periods, transfer restrictions, and information rights.

I will examine how FoodSwift protected confidentiality while ensuring founders remained committed through carefully drafted non-compete provisions. I will also address the delicate balance of ROFR, ROFO, and tag-along rights that protect all parties when anyone wants to sell their shares.

Stay tuned for Part 2.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications