Master UGC NET Constitutional and Administrative Law with complete syllabus coverage, 20 sample questions with explanations, previous year analysis, and expert preparation strategy. Score high in Unit 2.

I still remember my first UGC NET exam. I was sitting there, looking at a question about the Wednesbury unreasonableness test. I had read about it. I had even highlighted it in my notes. But at that moment, I couldn’t remember if it was part of Constitutional Law or Administrative Law. That confusion cost me marks I could have easily scored.

Here’s what nobody tells you when you start preparing: Constitutional and Administrative Law looks easy at first. You think, “I studied the Constitution in my LLB. I know about Fundamental Rights. This should be simple.”

Then the exam surprises you with questions you weren’t expecting, like matching different judges with their definitions, or arranging cases in the correct time order.

The truth? Unit II needs a specific type of preparation. You can’t just read everything and hope it works out. You need to understand how things connect, recognize which patterns keep showing up, and practice the different types of questions.

This guide is what I needed back then. It shows you clearly which topics actually matter in the exam, which question styles keep repeating, and how to solve each type step by step. We’ll go through 20 questions together, not just giving you answers, but showing you how to think through them.

Let’s make Unit II your strong point, not a last minute panic.

Why is Constitutional and Administrative Law Critical for UGC NET Success?

Constitutional and Administrative Law forms the backbone of legal education in India, and the National Testing Agency recognizes this through the weightage it assigns to Unit II.

Understanding why this unit matters goes beyond just knowing it carries more questions. It helps you approach your preparation with the seriousness and strategic focus this subject deserves.

How Many Questions Come from Unit II in UGC NET Law?

The question distribution from Constitutional and Administrative Law has shown significant variation across recent exam cycles, but one thing remains constant: this unit consistently delivers high returns for well prepared candidates. Analyzing the data helps you understand how much preparation time to allocate.

Year wise Question Distribution Analysis

The December 2023 cycle was exceptional for Constitutional and Administrative Law aspirants. According to analysis from previous year question compilations, approximately 27 questions appeared from Unit II, making it the highest contributing unit that cycle. This represented 27% of Paper II, an extraordinary concentration that rewarded candidates who had prioritized this subject.

The June 2024 re exam saw a moderation with approximately 12 to 15 questions from this unit. While lower than December 2023, this still represented a solid 12 to 15% of Paper II. The June 2025 cycle brought the count to around 9 to 12 questions, which, though the lowest in recent memory, still made Unit II a significant scoring opportunity.

What does this variation tell us?

The NTA does not follow a fixed template. Some cycles heavily favor Constitutional and Administrative Law; others distribute questions more evenly. Your preparation strategy must account for both scenarios by ensuring comprehensive coverage while recognizing high frequency topics.

Which Sub topics Within Unit II Yield Maximum Questions?

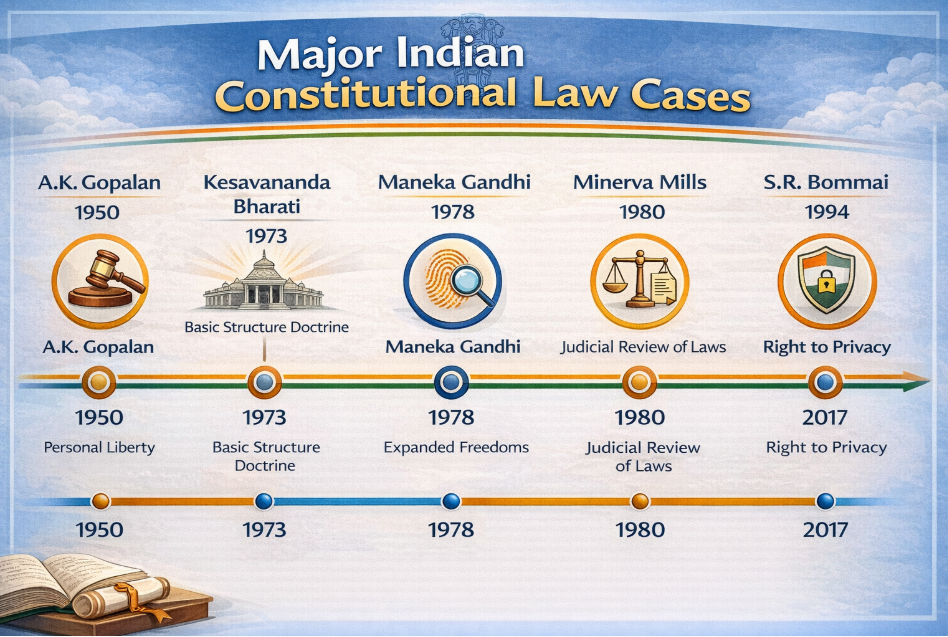

When you examine the actual questions asked, certain patterns emerge. Fundamental Rights, particularly Articles 14, 19, and 21, appear with remarkable consistency. The Basic Structure Doctrine and its evolution through cases like His Holiness Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala [1973 SC] feature regularly. Emergency provisions under Articles 352, 356, and 360 are perennial favorites.

On the Administrative Law side, Principles of Natural Justice dominate. Questions on Audi Alteram Partem (right to hearing) and Nemo Judex in Causa Sua (rule against bias) appear almost every cycle. Judicial review grounds, including the Wednesbury unreasonableness test, are tested frequently.

Match the following questions linking jurists to their definitions of administrative law have appeared in recent exams.

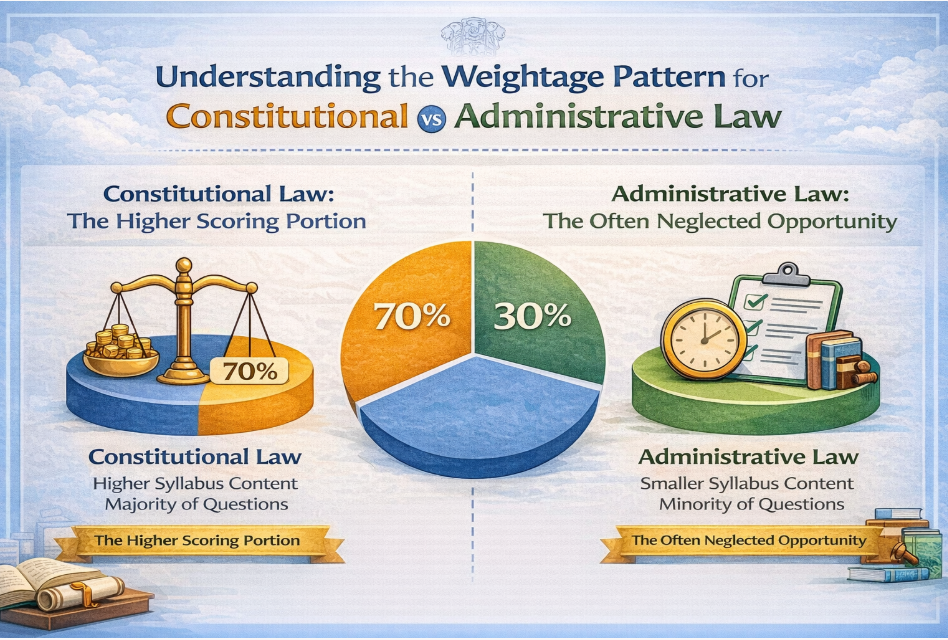

Understanding the Weightage Pattern for Constitutional vs Administrative Law

Within Unit II, Constitutional Law topics occupy roughly 70% of the syllabus content, while Administrative Law covers the remaining 30%. However, the question distribution does not always mirror this ratio precisely. Understanding this split helps you allocate preparation time effectively.

Constitutional Law: The Higher Scoring Portion

Constitutional Law questions typically outnumber Administrative Law questions in most cycles. This makes sense given the broader syllabus coverage, spanning from the Preamble through emergency provisions and special state provisions. The December 2023 cycle saw particularly heavy Constitutional Law testing, with multiple questions on fundamental rights interpretation and constitutional amendments.

Questions often test not just knowledge of Articles but their judicial interpretation. For instance, the June 2025 cycle included a question asking which Article is referred to as the “heart and soul” of the Indian Constitution, with Article 32 being the correct answer based on Dr. Ambedkar’s description. Such questions require you to know both the constitutional text and its contextual significance.

Administrative Law: The Often Neglected Opportunity

Here is where many candidates make a strategic error. Administrative Law receives less attention in most preparation strategies, yet it offers high yield scoring opportunities. The concepts are more contained, the case laws are fewer, and the principles are more predictable in how they are tested.

The June cycle included a matching question asking candidates to pair jurists like Wade, Garner, Griffith and Street, and Ivor Jennings with their respective definitions of Administrative Law. Such questions are straightforward if you have covered the basics but impossible if you have neglected this portion entirely.

What Does the UGC NET Constitutional and Administrative Law Syllabus Cover?

The official syllabus for Unit II is published by the NTA and remains relatively stable across exam cycles. However, simply reading the syllabus topics is not enough. You need to decode what each topic actually demands in terms of preparation depth and likely question formats.

Complete Syllabus Breakdown for Unit II

The NTA syllabus for Constitutional and Administrative Law lists ten broad topics. Each topic contains multiple sub areas that can generate questions. Understanding this structure helps you create a systematic study plan that covers everything without missing critical areas.

Constitutional Law Topics as per Official NTA Syllabus

The Constitutional Law portion covers seven major areas according to the official UGC NET syllabus. First, the Preamble, Fundamental Rights and Duties, and Directive Principles of State Policy form the foundational layer. Second, Union and State Executive structures and their interrelationship are covered. Third, Union and State Legislature along with distribution of legislative powers demand attention.

The fourth area covers the Judiciary comprehensively. Fifth, Emergency Provisions under Part XVIII require detailed study. Sixth, temporary, transitional, and special provisions for certain states, including the now abrogated Article 370, remain relevant. Seventh, the Election Commission of India and its constitutional mandate under Article 324 complete the Constitutional Law syllabus.

Administrative Law Topics as per Official NTA Syllabus

Administrative Law topics are more focused but equally important. The syllabus specifies three core areas.

First, the nature, scope, and importance of administrative law, including its relationship with constitutional law.

Second, the Principles of Natural Justice, covering both the hearing rule and the bias rule.

Third, judicial review of administrative actions and its various grounds.

While seemingly limited, these three areas encompass substantial conceptual depth. The nature and scope topic alone requires understanding various juristic definitions, the growth of administrative law in welfare states, and comparative perspectives on administrative justice systems.

How to Decode the Syllabus for Effective Preparation?

Reading syllabus points is one thing; understanding what the examiners actually test is another. The gap between syllabus language and actual questions can surprise unprepared candidates. Bridging this gap requires analyzing previous year questions alongside syllabus study.

Connecting Syllabus Points to Exam Question Patterns

Take “Preamble, fundamental rights and duties, directive principles” as a syllabus point. In actual exams, this translates to questions on whether the Preamble is part of the Constitution, what amendments modified the Preamble, how the Supreme Court has balanced fundamental rights against directive principles, and specific Article based questions testing your knowledge of exact provisions.

The June cycle asked about which Amendment inserted “Secularism, Socialism and Integrity” in the Preamble, with the 42nd Amendment being the correct answer. Such questions test precise constitutional knowledge. Another question asked candidates to arrange emergency provisions in their correct Article wise order, requiring familiarity with Article 352 (National Emergency), Article 356(State Emergency), and Article 360 (Financial Emergency).

Topics That Appear Every Year vs Rotating Topics

Some topics appear with near certainty. Fundamental Rights interpretation, Basic Structure Doctrine, Emergency Provisions, and Principles of Natural Justice fall into this category. If you skip these, you are guaranteed to lose marks regardless of which cycle you appear in.

Other topics rotate. Special provisions for states, Election Commission powers, and detailed legislative procedure questions appear less consistently. These should not be ignored but can receive slightly less intensive coverage compared to the guaranteed topics.

Constitutional Law: Topic wise Preparation Strategy

Constitutional Law forms the larger portion of Unit II and requires systematic coverage of multiple interconnected topics. Rather than reading randomly, approach this section with a structured plan that builds understanding progressively from foundational concepts to complex applications.

Preamble, Fundamental Rights, Duties, and Directive Principles

This cluster of topics forms the philosophical and rights based foundation of the Indian Constitution. Questions from this area test both your knowledge of specific provisions and your understanding of how courts have interpreted the relationship between different constitutional values.

The Preamble and Its Constitutional Significance

The Preamble declares India as a Sovereign, Socialist, Secular, Democratic Republic and commits to securing Justice, Liberty, Equality, and Fraternity for all citizens. The terms “Socialist” and “Secular” were added by the 42nd Constitutional Amendment in 1976, a fact frequently tested in UGC NET exams.

The constitutional status of the Preamble was settled in His Holiness Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala [1973], where the Supreme Court held that the Preamble is part of the Constitution. This overruled the earlier Berubari Union case position. The Preamble can be amended under Article 368 but its basic features cannot be destroyed. Understanding this evolution through case law is essential for answering interpretation based questions.

Fundamental Rights Under Part III: Articles 12 to 35

Part III of the Constitution of India contains Fundamental Rights from Articles 12 to 35 of the Constitution. Article 12 defines “State” for the purposes of Part III, a definition that has been expansively interpreted through cases like Ajay Hasia v. Khalid Mujib (1980 SC) . Article 13 declares laws inconsistent with fundamental rights as void, establishing the foundation for judicial review of legislation.

The substantive rights begin with Article 14 (Right to Equality), which has been transformed through judicial interpretation. In E.P. Royappa v. State of Tamil Nadu (1974 SC), the Supreme Court introduced the arbitrariness test, holding that Article 14 strikes at arbitrariness in state action. Article 19 contains six freedoms, with reasonable restrictions specified in clauses (2) through (6).

The recent Kaushal Kishore v. State of UP (2023) judgment held that fundamental rights under Article 19 are available against both state and non state actors, expanding the horizontal application of rights.

Article 21 has witnessed the most dramatic expansion. Beginning as a mere procedural safeguard, Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978 SC) transformed it into a substantive right requiring procedures that are fair, just, and reasonable.

Dr. B.R. Ambedkar called Article 32, which provides the right to constitutional remedies, the “heart and soul” of the Constitution. This description has been directly tested in UGC NET examinations.

Directive Principles of State Policy: Part IV Essentials

Directive Principles under Part IV (Articles 36 to 51 of the Constitution) are not enforceable by courts but are fundamental in governance. Article 37 explicitly states that DPSPs shall not be enforceable but are nevertheless fundamental in the governance of the country. Key directives include Article 39 (securing adequate means of livelihood), Article 41 (right to work), Article 43 (living wage), and Article 48A (protection of environment).

The tension between Fundamental Rights and DPSPs has generated significant jurisprudence. While Champakam Dorairajan v. State of Madras (1951 SC) initially subordinated DPSPs to Fundamental Rights, subsequent amendments and judicial developments have sought to harmonize them.

The Supreme Court in Minerva Mills v. Union of India (1980 SC) held that the harmony between Parts III and IV constitutes a basic feature of the Constitution.

Fundamental Duties Under Article 51A

The 42nd Amendment inserted Part IVA containing Fundamental Duties in Article 51A. Originally ten duties were listed; the 86th Amendment added an eleventh duty regarding education. These duties are not directly enforceable but have been used by courts as interpretive guides.

Article 51A(g) specifically mentions the duty to protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers, and wildlife, and to have compassion for living creatures. This provision has been tested in UGC NET exams asking candidates to identify which Part of the Constitution contains this environmental protection duty.

Interrelationship Between Fundamental Rights and DPSPs

The relationship between Fundamental Rights and Directive Principles represents one of the most examined areas in constitutional interpretation. The Constitution makers deliberately made Fundamental Rights justiciable and DPSPs non justiciable, creating an inherent tension when state policies promoting DPSPs conflict with individual rights.

The December cycle comprehension passage discussed this interrelationship, noting that the harmony and balance between Parts III and IV have been found to be among the basic features of the Constitution.

Candidates were asked to identify this from the passage. Understanding that this harmonious construction principle is a basic feature is crucial for answering such questions.

Union and State Executive: Powers and Interrelationships

The executive branch at both Union and State levels operates through complex constitutional mechanisms. Questions from this area test your understanding of presidential and gubernatorial powers, the role of councils of ministers, and the federalism dynamics between Centre and States.

The President: Powers, Election, and Removal

The President of India is elected indirectly by an electoral college comprising elected members of both Houses of Parliament and elected members of State Legislative Assemblies. Article 52 establishes the office, and Article 53 vests executive power in the President. However, Article 74(1) mandates that the President shall act on the aid and advice of the Council of Ministers.

Presidential powers include legislative powers (summoning, proroguing Parliament, ordinance making under Article 123), executive powers (appointments, command of armed forces), judicial powers (pardoning under Article 72), and emergency powers. The 42nd and 44th Amendments significantly affected presidential powers, particularly regarding emergencies and the binding nature of ministerial advice.

The Governor: Role, Discretionary Powers, and Controversies

The Governor, appointed by the President under Article 155, serves as the constitutional head of the State. Article 163 provides for a Council of Ministers to aid and advise the Governor, except when the Governor is required to exercise discretionary functions. This discretion has been the source of significant constitutional controversy.

The December cycle directly tested discretionary powers, asking under what circumstances the Governor exercises discretion. The correct options included appointment of Chief Minister when no party has a clear majority, dismissal of ministry, dissolution of Assembly, and submitting reports to the President for proclamation under Article 356.

Note that appointment of High Court judges was incorrect, as this involves the President, not gubernatorial discretion.

Council of Ministers at Union and State Levels

The Council of Ministers at both levels follows the Westminster model of collective responsibility. Article 75 governs the Union Council, specifying that Ministers are appointed by the President on the Prime Minister’s advice and hold office during the President’s pleasure. The 91st Amendment capped the Council’s size at 15% of the total House strength.

At the State level, Article 164 contains parallel provisions. The Chief Minister is appointed by the Governor, and other Ministers are appointed on the Chief Minister’s advice. The collective responsibility to the Legislative Assembly mirrors the Union pattern, ensuring parliamentary accountability of the executive.

Centre State Executive Relations

Executive relations between the Centre and States are governed by Articles 256 to 263 of the Constitution. Article 256 requires States to comply with Union laws and exercise executive power accordingly. Article 257 permits Union control over State executive power in certain matters. Article 258 allows the Union to confer powers on States with their consent.

Inter State Councils under Article 263 facilitate cooperative federalism. The Finance Commission under Article 280 addresses fiscal federalism concerns. Understanding these mechanisms helps answer questions on federal structure and Centre State dynamics.

Union and State Legislature: Distribution of Legislative Powers

The distribution of legislative powers between the Union and States is fundamental to India’s federal structure. Schedule VII contains three lists that demarcate legislative competence, but the distribution is not watertight, creating complex questions of constitutional interpretation.

Parliament: Composition, Powers, and Privileges

Parliament comprises the President, Lok Sabha (House of the People), and Rajya Sabha (Council of States) under Article 79. Lok Sabha consists of directly elected members with a maximum strength of 552. Rajya Sabha has a maximum strength of 250, with 238 elected by State Legislative Assemblies and 12 nominated by the President.

Parliamentary privileges under Articles 105 and 194 protect legislators’ freedom of speech and immunize parliamentary proceedings from court interference. The distinction between Money Bills (Article 110) and ordinary Bills affects the legislative process, with the Lok Sabha having primacy in financial matters.

State Legislature: Structure and Functions

State Legislatures may be unicameral (Legislative Assembly only) or bicameral (with Legislative Council). Article 168 establishes the State Legislature, which includes the Governor. The Legislative Assembly’s composition is determined by Article 170, while Article 171 governs Legislative Councils.

The legislative process at the State level parallels Parliament but with the Governor’s role in assent. Article 200 permits the Governor to reserve Bills for Presidential consideration, a power that has generated controversy when used for political purposes.

The Three Lists Under Schedule VII

Schedule VII’s three lists define legislative competence. The Union List (List I) contains 100 subjects including defence, foreign affairs, and atomic energy. The State List (List II) contains 61 subjects including public order, police, and land. The Concurrent List (List III) has 52 subjects where both can legislate, with Union law prevailing in case of conflict under Article 254.

The June cycle tested the distribution of legislative powers by asking candidates to arrange constitutional provisions in correct order. Understanding the Article sequence and the relationship between different lists is essential for such questions.

Doctrine of Pith and Substance and Colorable Legislation

When legislation’s validity is challenged on grounds of legislative competence, courts apply the pith and substance doctrine to determine its true nature. If the substance falls within the legislating body’s competence, incidental encroachment on other lists does not invalidate it.

Colorable legislation refers to attempts to do indirectly what cannot be done directly. If Parliament lacks power to enact certain legislation, it cannot achieve the same result by using available powers as a pretense. The court looks beyond form to substance in such challenges.

Residuary Powers and Parliamentary Supremacy in Certain Matters

Article 248 grants Parliament residuary power to legislate on matters not enumerated in any list. Entry 97 of List I reinforces this by including “any other matter not enumerated in List II or List III.” This differs from the American model where residuary powers vest in States.

Parliament can also legislate on State List matters under specific circumstances: under Article 249 when Rajya Sabha passes a resolution by two thirds majority that legislation is necessary in national interest; under Article 250 during a Proclamation of Emergency; under Article 252 when two or more States request; and under Article 253 for implementing international agreements.

The Judiciary Under the Indian Constitution

The Indian judiciary, particularly the Supreme Court, plays a crucial role in constitutional interpretation and protection of rights. Questions test both structural aspects of the judicial system and substantive doctrines developed through judicial pronouncements.

Supreme Court: Composition, Jurisdiction, and Powers

Article 124 establishes the Supreme Court of India, consisting of the Chief Justice and such other judges as Parliament may prescribe. Currently, the sanctioned strength is 34 including the CJI.

Judges are appointed by the President after consultation with the Chief Justice and other judges as prescribed, though the collegium system has evolved through judicial interpretation.

The Supreme Court exercises original jurisdiction under Article 131 in disputes between the Union and States or between States. Its appellate jurisdiction covers constitutional matters (Article 132), civil matters (Article 133), criminal matters (Article 134), and appeals by special leave (Article 136). Article 32 grants writ jurisdiction for enforcement of Fundamental Rights, which Dr. Ambedkar described as making the Supreme Court the protector and guarantor of fundamental rights.

High Courts: Structure, Powers, and Jurisdiction

High Courts, established under Article 214, are the highest courts of original jurisdiction in States. Article 226 grants High Courts writ jurisdiction broader than the Supreme Court’s Article 32 power, as High Courts can issue writs for enforcement of any legal right, not just Fundamental Rights.

The superintendence power under Article 227 allows High Courts to oversee subordinate courts and tribunals within their territorial jurisdiction. Transfer of judges between High Courts under Article 222 requires Presidential order after consultation with the Chief Justice of India.

Judicial Review: Scope and Limitations

Judicial review is the power of courts to examine the constitutional validity of legislative and executive actions. In Marbury v. Madison (1803), the US Supreme Court first established this doctrine, which the Indian Constitution implicitly adopts.

In India, judicial review operates under Articles 13, 32, 226, 227, and 136. However, it is subject to limitations. Constitutional amendments enjoy presumption of constitutionality. Courts cannot substitute their wisdom for legislative policy unless the legislation violates constitutional provisions. The basic structure limitation on judicial review of amendments was established in Kesavananda Bharati.

Independence of Judiciary: Constitutional Safeguards

Judicial independence is secured through multiple constitutional provisions. Judges’ salaries and service conditions are charged on the Consolidated Fund and cannot be varied to their disadvantage after appointment (Articles 125, 221). Removal requires impeachment by Parliament under Articles 124(4) and 217. Conduct of judges cannot be discussed in Parliament except during impeachment proceedings.

The collegium system, though not explicitly in the Constitution, evolved through the Three Judges Cases as a safeguard against executive interference in appointments. This system, while controversial, represents judicial assertion of institutional independence.

Emergency Provisions Under Part XVIII

Emergency provisions represent the Constitution’s mechanism for handling extraordinary situations. These provisions have been tested extensively in UGC NET exams, particularly regarding their scope, effects, and the safeguards introduced through amendments.

National Emergency Under Article 352

Article 352 empowers the President to proclaim a National Emergency when India’s security is threatened by war, external aggression, or armed rebellion. The term “internal disturbance” was replaced with “armed rebellion” by the 44th Amendment to prevent misuse. The proclamation must be based on written advice from the Cabinet.

A National Emergency must be approved by Parliament within one month by a special majority. Once approved, it can continue indefinitely with parliamentary approval every six months. Three National Emergencies have been proclaimed: 1962 (Chinese aggression), 1971 (Bangladesh war), and 1975 (internal emergency).

State Emergency (President’s Rule) Under Article 356

Article 356 allows the President to proclaim emergency if satisfied that State governance cannot be carried on in accordance with constitutional provisions. This provision has been most frequently invoked and most controversially used. The Bommai judgment established critical limitations.

In S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994 SC), the Supreme Court held that Article 356 is subject to judicial review, the State Assembly should not be dissolved before parliamentary approval, and the power must be used sparingly. The Governor’s report is not conclusive; courts can examine whether relevant material justified the proclamation.

Financial Emergency Under Article 360

Article360 permits proclamation of Financial Emergency if the President is satisfied that India’s financial stability or credit is threatened. This emergency has never been proclaimed. Unlike National Emergency, there is no time limit specified; it continues until revoked.

The June 2024 re-exam asked about the maximum period of Financial Emergency operation without parliamentary approval. Unlike National Emergency (one month), Financial Emergency must be approved within two months to continue. If Parliament does not approve within two months, it ceases to operate.

Effects of Emergency on Fundamental Rights

National Emergency has significant effects on Fundamental Rights. Article 358 automatically suspends Article 19 during emergencies proclaimed on grounds of war or external aggression only. The June 2025 cycle tested this, asking on which grounds Article 19 is automatically suspended. The correct answer was war and external aggression only; armed rebellion does not trigger automatic Article 19 suspension.

Article 359 allows the President to suspend the right to move courts for enforcement of Fundamental Rights during emergencies. However, the 44th Amendment provided that Articles 20 and 21 cannot be suspended even during emergencies, protecting the rights against ex post facto laws and right to life.

Safeguards Against Misuse: The 44th Amendment and Beyond

The 1975 to 1977 internal emergency exposed vulnerabilities in the emergency framework. The 44th Amendment introduced crucial safeguards. “Internal disturbance” was replaced with “armed rebellion” to raise the threshold for emergency proclamation. Written Cabinet advice was mandated. Articles 20 and 21 were made non suspendable.

The amendment also strengthened parliamentary control by requiring special majority (not simple majority) for emergency approval and continuation. Judicial review of emergency proclamations was implicitly protected. These safeguards represent lessons learned from emergency misuse.

Special Provisions for Certain States and Election Commission

Part XXI of the Constitution contains temporary, transitional, and special provisions for certain states. Additionally, the Election Commission’s role in ensuring free and fair elections forms an important constitutional topic frequently tested in examinations.

Article 370 and Its Abrogation: Constitutional Implications

Article 370, now abrogated, granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir. It limited Parliament’s legislative power to defence, foreign affairs, and communications. The State had its own Constitution, and other central laws required State Constituent Assembly concurrence.

In 2019, Presidential orders modified Article 370, and a subsequent order effectively abrogated it. Article 35A of the Constitution , which allowed the State legislature to define “permanent residents” and confer special rights, was also rendered inoperative. The constitutional validity of this action was upheld by the Supreme Court in 2023.

Special Provisions for Other States Under Part XXI

Several northeastern states and other regions have special constitutional provisions. Article 371A provides special provisions for Nagaland regarding religious and social practices. Article 371B gives Assam special provisions for tribal areas. Articles 371C through 371J contain provisions for Manipur, Andhra Pradesh (bifurcated to include Telangana), Sikkim, Mizoram, Arunachal Pradesh, Goa, and Karnataka respectively.

The June 2025 cycle asked which Schedule contains special provisions for administration and control of Scheduled Areas, with the Fifth Schedule being the correct answer. The Sixth Schedule applies to tribal areas in Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

Election Commission of India: Composition and Powers Under Article 324

Article 324 vests superintendence, direction, and control of elections to Parliament, State Legislatures, and offices of President and Vice President in the Election Commission. Originally consisting of a single Chief Election Commissioner, it became multi member in 1989, now typically having three members.

The Chief Election Commissioner enjoys security of tenure comparable to a Supreme Court judge and can only be removed through impeachment. Other Election Commissioners can be removed only on the CEC’s recommendation. This asymmetry has been debated but protects the CEC’s independence.

Electoral Reforms and Recent Developments

Recent electoral reforms include the introduction of NOTA (None of the Above) option, validated in People’s Union for Civil Liberties v. Union of India (2013 SC). Electoral bonds, though now struck down, represented attempted reform of political funding. The December 2023 cycle included PUCL case in questions relating to constitutional developments.

Voter Verified Paper Audit Trail (VVPAT) machines were introduced to enhance electoral transparency. Delimitation exercises and reservation of seats continue under constitutional provisions. Understanding these developments helps answer questions on contemporary constitutional issues.

Administrative Law: Topic wise Preparation Strategy

Administrative Law, though occupying less syllabus space than Constitutional Law, offers concentrated scoring opportunities. The concepts are more defined, the case laws more specific, and the question patterns more predictable. Mastering this portion efficiently can significantly boost your Unit II score.

What is Administrative Law and Why Does It Matter?

Administrative Law governs how administrative authorities exercise their powers and provides mechanisms for controlling such exercise. In a welfare state where government touches almost every aspect of citizens’ lives, understanding administrative law is essential both academically and practically.

Nature, Scope, and Importance of Administrative Law

Administrative Law can be defined in multiple ways, and UGC NET examinations frequently test these juristic definitions. I.P. Massey defines it as the law relating to administration, determining the organization, powers, and duties of administrative authorities. Wade defines it as the law relating to the control of governmental power.

The scope of administrative law encompasses the organization of administrative machinery, powers of administrative authorities (including delegated legislation), judicial and quasi judicial functions, and remedies against administrative actions. Its importance has grown exponentially with the expansion of state functions in welfare economies.

Relationship Between Constitutional Law and Administrative Law

Constitutional Law and Administrative Law are interconnected branches of public law. As Maitland observed, Constitutional Law describes the organs of government at rest, while Administrative Law describes them in motion. Constitutional Law provides the framework; Administrative Law fills in the operational details.

The relationship is both complementary and hierarchical. Administrative Law emanates from Constitutional Law and cannot contradict it. Any administrative action violating constitutional provisions is void. Yet the two are so intertwined that Keith described attempts to distinguish them as “logically impossible and practically inconvenient.”

In India, the Constitution itself contains administrative law provisions. Articles 323A and 323B establish tribunals for administrative adjudication. Fundamental Rights under Part III apply to administrative actions. The Directive Principles guide administrative policy making.

Growth of Administrative Law in the Welfare State

The growth of administrative law reflects the transformation from a laissez faire state to a welfare state. When government functions expanded beyond traditional police powers to include regulation of industry, provision of social services, and economic planning, traditional methods of control proved inadequate.

Administrative authorities acquired legislative powers (rule making), judicial powers (adjudication), and combined powers that traditional separation of powers would not permit. This concentration necessitated new control mechanisms, giving rise to administrative law as a distinct discipline.

The Franks Committee in Britain and the Law Commission’s reports in India reflect efforts to systematize administrative justice.

Principles of Natural Justice: The Foundation of Fair Administration

Natural Justice principles represent fundamental requirements of procedural fairness that administrative authorities must observe. These principles, developed through centuries of common law evolution, ensure that administrative power is exercised fairly and reasonably.

Audi Alteram Partem: The Right to Be Heard

Audi alteram partem, meaning “hear the other side,” is the first pillar of natural justice. It requires that no person should be condemned unheard. Before an administrative authority takes any action adversely affecting a person’s rights, that person must be given an opportunity to present their case.

The components of fair hearing include notice of the case to be met, disclosure of material intended to be relied upon, reasonable time to prepare a response, opportunity to present evidence and arguments, and access to legal representation where appropriate.

In A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India (1970 SC), the Supreme Court extended natural justice requirements to administrative functions, not just quasi judicial ones. This expansion significantly broadened the hearing rule’s application across governmental decision making.

Nemo Judex in Causa Sua: Rule Against Bias

Nemo judex in causa sua means “no one should be a judge in their own cause.” This rule ensures that decision makers are free from bias, both actual and apparent. Even the appearance of bias can vitiate proceedings.

The rule reflects the fundamental principle that justice must not only be done but must be seen to be done. Lord Hewart’s famous dictum in R v. Sussex Justices captures this: “Justice should not only be done, but should manifestly and undoubtedly be seen to be done.”

Bias can disqualify a decision maker even without proof of actual unfairness. The test is whether a reasonable person, knowing all relevant facts, would apprehend that there was a real possibility of bias.

Types of Bias: Personal, Pecuniary, Subject Matter, and Departmental

Pecuniary bias, the strictest category, involves financial interest in the decision. In Dimes v. Grand Junction Canal (1852), the House of Lords held that Lord Chancellor Cottenham’s shareholding in a company party to litigation disqualified him, regardless of actual bias.

Personal bias involves personal relationship with parties or prejudice regarding the subject matter. In Mineral Development Ltd. v. State of Bihar (1959 SC), personal connections were examined. Subject matter bias arises when a decision maker has prejudged the issue. In Gullapalli Nageswara Rao v. A.P. SRTC (1959 SC), the Transport Minister who initiated the proposal could not also approve it.

Departmental or official bias arises from the decision maker’s position in the administrative hierarchy. In State of West Bengal v. Shivananda Pathak (1998 SC), official bias was examined. This type presents unique challenges because some institutional interest is inherent in administrative decision making.

Judicial obstinacy, another form, involves a judge refusing to consider relevant material or displaying a closed mind.

Exceptions to Natural Justice Principles

Natural justice principles, though fundamental, admit exceptions in certain circumstances. Where legislative provisions explicitly exclude natural justice, courts may respect such exclusion if the exclusion is constitutional and reasonable. Emergency situations requiring immediate action may justify abbreviated procedures.

Procedural requirements may also yield where the affected person waives the right, where giving a hearing would be futile, where strict compliance is impracticable, or where confidentiality concerns override procedural fairness. Each exception, however, is narrowly construed, and authorities bear the burden of justifying departures from fair procedures.

Consequences of Violation of Natural Justice

Violation of natural justice principles generally renders administrative decisions void or voidable. In Ridge v. Baldwin (1964), Lord Reid held that decisions made in breach of natural justice are void ab initio. However, subsequent cases have suggested that the consequence may depend on the nature and gravity of the breach.

The affected person may seek judicial review through writ jurisdiction (certiorari to quash, prohibition to prevent, mandamus to compel). Administrative decisions can be set aside and remanded for fresh consideration following proper procedure. In some cases, courts may substitute their own decision if the facts permit only one conclusion.

Judicial Review of Administrative Actions

Judicial review is the mechanism through which courts supervise administrative action to ensure it remains within legal bounds. Unlike appeals, which examine the merits of decisions, judicial review focuses on the legality, rationality, and procedural propriety of administrative actions.

What is Judicial Review in Administrative Law?

Judicial review of administrative action is the court’s power to examine whether administrative authorities have acted within their legal powers and in accordance with required procedures. It is supervisory, not appellate; courts do not substitute their judgment for that of administrators on policy matters.

The purpose is to ensure that administrators operate within the four corners of law, observe procedural requirements, and do not act unreasonably or arbitrarily. Judicial review protects citizens against administrative overreach while respecting administrative expertise and discretion within lawful bounds.

Grounds of Judicial Review: Illegality

Illegality as a ground for judicial review means the decision maker did not correctly understand the law that regulates their power, or failed to give effect to it. This includes acting without jurisdiction, exceeding jurisdiction, and failing to exercise jurisdiction when legally required.

Ultra vires doctrine underlies this ground. An administrator’s action is ultra vires if it exceeds the powers granted by the parent statute. This includes both substantive ultra vires (exceeding scope of power) and procedural ultra vires (failing to follow mandatory procedures).

Relevant and irrelevant considerations also fall under illegality. Administrators must consider all legally relevant factors and must not take irrelevant factors into account. Failure to do so renders the decision reviewable.

Grounds of Judicial Review: Irrationality (Wednesbury Unreasonableness)

Irrationality, also known as Wednesbury unreasonableness after Associated Provincial Picture Houses v. Wednesbury Corporation (1948), means the decision is so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could have reached it. This is a high threshold, respecting administrative discretion while checking its abuse.

Lord Greene’s formulation required unreasonableness of an extreme kind, something “so outrageous in its defiance of logic or accepted moral standards that no sensible person who had applied his mind to the question could have arrived at it.” This standard has been refined but remains the benchmark.

Understanding when courts will intervene on irrationality grounds, and when they will defer to administrative judgment, is essential.

Grounds of Judicial Review: Procedural Impropriety

Procedural impropriety encompasses failure to observe procedural rules established by statute, regulations, or common law natural justice. This ground recognizes that fair procedures are not mere technicalities but substantive protections for affected persons.

Breach of natural justice falls within procedural impropriety. So does failure to follow mandatory procedural requirements imposed by law. The distinction between mandatory and directory procedures affects whether breach invalidates the action or merely renders it irregular.

Legitimate expectation, a relatively recent development, extends procedural protection to situations where established practices or prior representations create expectations of being heard before changes are implemented.

Limitations on Judicial Review: Ouster Clauses and Their Validity

Legislatures sometimes include ouster clauses attempting to exclude judicial review. Such clauses take various forms: “final and conclusive,” “shall not be called in question in any court,” or “no court shall have jurisdiction.” Their validity is constitutionally contested.

In India, Article 226 and Article 32 have been held to be part of the basic structure. Complete ouster of High Court or Supreme Court jurisdiction would be unconstitutional. Partial limitations may be valid if they leave some avenue for review and protect fundamental rights. Anisminic Ltd. v. Foreign Compensation Commission (1969) in England demonstrated judicial willingness to read ouster clauses narrowly.

Difference Between Judicial Review and Appeal

Understanding the distinction between judicial review and appeal is fundamental. On appeal, the appellate body can examine both facts and law and substitute its own decision. On judicial review, courts examine only legality, not merits, and typically remand rather than substitute their judgment.

Appeals lie as of right where statutes provide them. Judicial review is discretionary, requiring the petitioner to demonstrate sufficient interest and exhaust alternative remedies. Appeals examine whether the decision was right; judicial review examines whether the decision was lawfully made.

Landmark Case Laws for Constitutional and Administrative Law

Case law forms the backbone of Constitutional and Administrative Law understanding. UGC NET examinations frequently test landmark judgments, often requiring candidates to match cases with principles or arrange them chronologically. Systematic knowledge of essential cases significantly enhances scoring potential.

Essential Constitutional Law Cases for UGC NET

Constitutional law has been shaped through decades of Supreme Court jurisprudence. Knowing the facts, holdings, and significance of landmark cases is essential for answering direct questions and understanding broader constitutional principles.

Basic Structure Doctrine Cases

His Holiness Kesavananda Bharati v State of Kerala [1973 SC] represents the most significant constitutional judgment in Indian history. The 13 judge bench, by a 7:6 majority, held that Parliament’s amending power under Article 368 is subject to the implicit limitation that basic features of the Constitution cannot be destroyed.

The basic features identified include supremacy of the Constitution, republican and democratic form of government, secular character, separation of powers, federal character, unity and integrity of the nation, sovereignty, dignity of the individual and fundamental rights, rule of law, judicial review, and balance between fundamental rights and directive principles. Different judges emphasized different features, but the core principle remains settled.

Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India (1980 SC) reaffirmed the basic structure doctrine and struck down clauses of the 42nd Amendment that sought to remove all limitations on amending power. The court held that limited amending power is itself a basic feature. Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975 SC) established that the basic structure doctrine limits amendments but not ordinary legislation.

Fundamental Rights Interpretation Cases

Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (1978 SC) transformed Article 21 interpretation. The Court held that procedure established by law must be right, just, fair, and reasonable, not arbitrary, fanciful, or oppressive. This brought substantive due process into Indian jurisprudence without explicitly adopting the American terminology.

A.K. Gopalan v. State of Madras (1950 SC), the earlier position, had isolated each fundamental right from others. Maneka Gandhi’s interc onnectedness approach read Articles 14, 19, and 21 together, requiring laws affecting personal liberty to satisfy reasonableness under Article 14 and comply with Article 19 restrictions.

K.S. Puttaswamy v. Union of India (2017 SC) recognized the right to privacy as a fundamental right under Article 21, overruling the earlier position in M.P. Sharma and Kharak Singh.

Emergency Powers and Federalism Cases

S.R. Bommai v. Union of India (1994 SC) established crucial limitations on Article 356. The Court held that the President’s satisfaction is subject to judicial review, the State Assembly should not be dissolved before parliamentary approval, secularism is a basic feature, and actions under Article 356 can be reviewed on grounds of mala fides, extraneous purposes, and irrelevant considerations.

The case arose from multiple State government dismissals. The Court’s guidelines significantly curtailed misuse of President’s Rule, establishing that political instability alone does not justify Article 356 invocation.

Essential Administrative Law Cases for UGC NET

Administrative law cases establish principles governing administrative action. These cases are frequently tested through matching questions requiring candidates to link cases with principles or identify which case established particular doctrines.

Natural Justice Landmark Judgments

A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India (1970 SC) expanded natural justice requirements to administrative functions, not just quasi judicial ones. The case involved selection committee members who were themselves candidates. The Court held that such participation violated natural justice principles.

Ridge v. Baldwin (1964), though an English case, is frequently referenced in Indian administrative law. Lord Reid’s judgment revived natural justice principles that had been narrowly applied in earlier decades. The case established that natural justice requirements apply wherever rights are affected, not just in judicial or quasi judicial proceedings.

Gullapalli Nageswara Rao v. A.P. SRTC (1959 SC) illustrates subject matter and official bias. The Transport Minister who initiated the proposal for nationalizing transport routes could not also approve the scheme.

Judicial Review of Administrative Action Cases

Associated Provincial Picture Houses v. Wednesbury Corporation (1948) established the irrationality standard for judicial review. Though an English case, Wednesbury unreasonableness has been adopted in Indian administrative law as a ground for reviewing discretionary decisions.

Council of Civil Service Unions v. Minister for Civil Service (1985), the GCHQ case, systematized judicial review grounds into illegality, irrationality, and procedural impropriety. This tripartite classification, articulated by Lord Diplock, is now the standard framework for analyzing judicial review grounds.

Understanding both the doctrines and their Indian applications through cases like Tata Cellular v. Union of India helps answer application based questions.

10 Sample Questions on Constitutional Law with Detailed Explanations

Practice questions modeled on actual UGC NET patterns help you understand how concepts translate into exam questions. Each question below mirrors the style, complexity, and format you will encounter. Work through these before checking explanations to assess your preparation.

Question 1 (Fundamental Rights)

Which of the following Articles is referred to as the “heart and soul” of the Indian Constitution?

(A) Article 14 (B) Article 19 (C) Article 21 (D) Article 32

Answer: (D) Article 32

Explanation: Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, Chairman of the Drafting Committee, described Article 32 as the “heart and soul” of the Constitution during Constituent Assembly debates. Article 32 provides the right to constitutional remedies, empowering citizens to directly approach the Supreme Court for enforcement of Fundamental Rights through writs.

While Articles 14, 19, and 21 are substantive rights, Article 32 provides the mechanism for their enforcement, making it foundational to the rights framework.

Question 2 (Basic Structure Doctrine)

In which of the following cases has it been held that the doctrine of basic features does not constitute a limitation on the legislature while enacting ordinary legislation?

(A) Kesavananda Bharati v. State of Kerala (B) Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (C) Minerva Mills Ltd. v. Union of India (D) Golaknath v. State of Punjab

Answer: (B) Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain

Explanation: In Indira Gandhi v. Raj Narain (1975 SC), the Supreme Court clarified that the basic structure doctrine limits only the constituent power (power to amend the Constitution) and not the ordinary legislative power.

Parliament’s power to enact ordinary legislation is subject to constitutional provisions and judicial review but not to the basic structure test. Kesavananda Bharati established the doctrine; Minerva Mills reaffirmed it regarding amendments; Golaknath preceded Kesavananda with a different approach to amendability.

Question 3 (Emergency Provisions)

Article 19 of the Constitution of India is automatically suspended if the proclamation of Emergency is declared on the grounds of:

(A) War and external aggression only (B) War, external aggression, and armed rebellion (C) Armed rebellion only (D) War and armed rebellion only

Answer: (A) War and external aggression only

Explanation: Under Article 358, Fundamental Rights under Article 19 are automatically suspended only when National Emergency is proclaimed on grounds of war or external aggression. If the emergency is declared on grounds of armed rebellion (the term that replaced “internal disturbance” after the 44th Amendment), Article 19 is NOT automatically suspended.

The President must specifically suspend Article 19 through an order under Article 359 in such cases. This distinction, introduced by the 44th Amendment to prevent repetition of 1975 emergency excesses, is frequently tested.

Question 4 (Distribution of Legislative Powers)

In which of the following circumstances can Parliament legislate with respect to matters in the State List?

(A) When the President directs (B) In the national interest with Rajya Sabha resolution (C) During Financial Emergency only (D) When the Governor requests

Answer: (B) In the national interest with Rajya Sabha resolution

Explanation: Under Article 249, if Rajya Sabha passes a resolution by two thirds majority declaring that it is necessary in the national interest for Parliament to make laws on any matter in the State List, Parliament can legislate on that matter.

Other circumstances include: during National Emergency (Article 250), when two or more States consent (Article 252), for implementing international treaties (Article 253), and during President’s Rule (Article 356).

Question 5 (Union and State Executive)

Under what circumstances can the Governor be called to exercise discretion under Article 163?

(A) Appointment of Chief Minister, dismissal of ministry, submitting report under Article 356 (B) Appointment of High Court judges, legislative assent, summoning assembly (C) Appointing Council of Ministers, proroguing assembly, addressing legislature (D) Reserving bills for President, judicial appointments, emergency proclamation

Answer: (A) Appointment of Chief Minister, dismissal of ministry, submitting report under Article 356

Explanation: Article 163 provides that the Governor shall act on ministerial advice except where required to exercise discretion. Discretionary situations include: appointing Chief Minister when no party has clear majority, dismissing a ministry or dissolving the assembly, submitting reports to the President for Article 356 proclamation, and reserving bills for President’s consideration. Appointment of High Court judges is not a gubernatorial power but involves the President.

Question 6 (Judiciary)

The power of judicial review was first adopted/applied by the Supreme Court of USA in which case?

(A) Ridge v. Baldwin (B) Marbury v. Madison (C) Brown v. Board of Education (D) Roe v. Wade

Answer: (B) Marbury v. Madison

Explanation: In Marbury v. Madison (1803), Chief Justice John Marshall established judicial review when the US Supreme Court struck down a portion of the Judiciary Act of 1789 as unconstitutional. This landmark case established that courts have the power to review legislative and executive actions for constitutional compliance.

Though the Indian Constitution does not explicitly provide for judicial review like the US Constitution, Articles 13, 32, 136, and 226 implicitly grant this power.

Question 7 (Preamble and Constitutional Amendments)

Which Amendment inserted the words “Secularism, Socialism and Integrity” in the Preamble of the Indian Constitution?

(A) 42nd Amendment (B) 44th Amendment (C) 73rd Amendment (D) 86th Amendment

Answer: (A) 42nd Amendment

Explanation: The 42nd Constitutional Amendment (1976), passed during the Emergency, inserted the words “Socialist,” “Secular,” and “Integrity” in the Preamble. The Preamble originally described India as a “Sovereign Democratic Republic”; it now reads “Sovereign Socialist Secular Democratic Republic.” “Unity and Integrity” replaced just “Unity.” This extensive amendment made numerous other changes, many of which were reversed by the 44th Amendment.

Question 8 (Directive Principles)

“To protect and improve the natural environment including forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife and to have compassion for living creatures” is provided under which Part of the Indian Constitution?

(A) Fundamental Rights (B) Fundamental Duties (C) Directive Principles of State Policy (D) Preamble

Answer: (B) Fundamental Duties

Explanation: This provision appears in Article 51A(g), which is part of Fundamental Duties under Part IVA. Article 51A(g) imposes a duty on every citizen to protect and improve the natural environment.

However, environmental protection also appears in Article 48A (a Directive Principle requiring the State to protect the environment). The precise wording about “forests, lakes, rivers and wildlife” and “compassion for living creatures” specifically appears in Article 51A(g), the Fundamental Duty.

Question 9 (Election Commission)

Which Schedule of the Indian Constitution contains special provisions for the administration and control of Scheduled Areas in several States?

(A) Third Schedule (B) Fifth Schedule (C) Seventh Schedule (D) Ninth Schedule

Answer: (B) Fifth Schedule

Explanation: The Fifth Schedule (Articles 244(1)) contains provisions for administration and control of Scheduled Areas and Scheduled Tribes in states other than Assam, Meghalaya, Tripura, and Mizoram.

The Sixth Schedule applies to tribal areas in those northeastern states. The Third Schedule contains oath forms; the Seventh Schedule contains the three legislative lists; the Ninth Schedule contains laws protected from judicial review under Article 31B.

Question 10 (Special Provisions for States)

Arrange the following cases relating to Uniform Civil Code in the chronological order of their pronouncement:

(A) Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum (B) Sarla Mudgal v. Union of India (C) ABC v. State (NCR of Delhi) (D) Jorden Diengdeh v. S.S. Chopra (E) John Vallamattom v. Union of India

Answer: A, D, B, E, C (Shah Bano 1985, Jorden Diengdeh 1985, Sarla Mudgal 1995, John Vallamattom 2003, ABC 2015)

Explanation: These cases represent the Supreme Court’s evolving position on Article 44 (Uniform Civil Code). Mohd. Ahmed Khan v. Shah Bano Begum (1985 SC) first urged the government to implement UCC while deciding Muslim women’s maintenance rights.

Jorden Diengdeh v S.S. Chopra ( 1985 SC) addressed inter religious marriage complications. Sarla Mudgal v Union of India (1995 SC) dealt with Hindu men converting to Islam to practice bigamy. John Vallamattom v Union of India (2003 SC) addressed discriminatory provisions in Indian Succession Act. ABC v. State (2015 SC) involved single mother’s guardianship rights.

10 Sample Questions on Administrative Law with Detailed Explanations

Administrative Law questions in UGC NET often test conceptual understanding through matching, assertion reason, and direct recall formats. The following questions cover the key areas of natural justice, judicial review, and administrative law definitions that appear regularly.

Question 1 (Principles of Natural Justice: Audi Alteram Partem)

Which of the following is NOT a component of the principle of Audi Alteram Partem?

(A) Notice of the charges or allegations (B) Opportunity to cross examine witnesses (C) Right to appeal to a higher authority (D) Opportunity to present evidence and arguments

Answer: (C) Right to appeal to a higher authority

Explanation: Audi alteram partem (hear the other side) requires: notice of the case to be met, disclosure of material to be relied upon, reasonable opportunity to respond, and opportunity to present evidence and arguments.

The right to appeal is a statutory right, not a natural justice requirement. While many statutes provide appeal mechanisms, failure to provide an appeal does not violate natural justice if the original hearing was fair. Understanding this distinction helps answer questions on what natural justice minimally requires versus what statutes additionally provide.

Question 2 (Rule Against Bias)

Match the following types of bias with the correct case laws:

| List I (Type of Bias) | List II (Case Law) |

| A. Pecuniary Bias | I. Gullapalli Nageswara Rao v. A.P. SRTC |

| B. Personal Bias | II. Dimes v. Grand Junction Canal |

| C. Official Bias | III. Mineral Development Ltd. v. State of Bihar |

| D. Judicial Obstinacy | IV. State of W.B. v. Shivananda Pathak |

Answer: A-II, B-III, C-I, D-IV

Explanation: Pecuniary bias (financial interest) is illustrated by Dimes v. Grand Junction Canal where Lord Chancellor Cottenham’s shareholding disqualified him. Personal bias involves personal relationships or prejudice, as examined in Mineral Development Ltd.

Official/subject matter bias arises when officials participate in decisions they initiated, as in Gullapalli Nageswara Rao where the Transport Minister couldn’t approve his own proposal. Judicial obstinacy refers to judges refusing to consider relevant material, as discussed in Shivananda Pathak.

Question 3 (Judicial Review: Grounds)

Which of the following is NOT a ground for judicial review of administrative action as categorized in CCSU v. Minister for Civil Service (GCHQ case)?

(A) Illegality (B) Irrationality (C) Procedural impropriety (D) Error of fact

Answer: (D) Error of fact

Explanation: Lord Diplock in the GCHQ case (1985) systematized judicial review grounds into three categories: illegality (decision maker misunderstood the law), irrationality (Wednesbury unreasonableness), and procedural impropriety (breach of natural justice or statutory procedures).

Error of fact is generally not a ground for judicial review unless it is a jurisdictional fact or the error is so fundamental as to constitute illegality. Courts on judicial review examine legality, not correctness of factual determinations, which is an appellate function.

Question 4 (Definition and Scope of Administrative Law)

Match the jurists with their definitions of Administrative Law:

| List I (Jurists) | List II (Definition) |

| A. Wade | I. Law relating to administration determining organization, powers and duties |

| B. Garner | II. Main object is operation and control of administrative authorities |

| C. Griffith & Street | III. Rules recognized by courts as law relating to administration |

| D. Ivor Jennings | IV. Law relating to control of government power |

Answer: A-IV, B-III, C-II, D-I

Explanation: Wade defined administrative law as law relating to control of governmental power. Garner emphasized rules recognized by courts as law relating to administration. Griffith and Street focused on the operation and control of administrative authorities.

Ivor Jennings defined it as law relating to administration, determining organization, powers, and duties of administrative authorities. Knowing these standard definitions is essential as they are tested directly.

Question 5 (Administrative Tribunals)

Which Articles were added to the Constitution of India to facilitate the establishment of specific Tribunals for Administrative Justice?

(A) Articles 124A and 233A (B) Articles 323A and 323B (C) Articles 338A and 338B (D) Articles 324A and 324B

Answer: (B) Articles 323A and 323B

Explanation: The 42nd Amendment inserted Articles 323A and 323B to enable tribunal establishment. Article 323A provides for administrative tribunals (like CAT for service matters), while Article 323B enables tribunals for other matters like taxation, foreign exchange, industrial disputes, etc. Articles 338A and 338B relate to National Commissions for Scheduled Tribes and Backward Classes respectively, not tribunals.

Question 6 (Delegated Legislation)

Which of the following is NOT a valid ground for challenging delegated legislation?

(A) Ultra vires the parent Act (B) Violation of constitutional provisions (C) Unreasonableness (D) Mere inconvenience to affected parties

Answer: (D) Mere inconvenience to affected parties

Explanation: Delegated legislation can be challenged on grounds of being ultra vires (exceeding powers granted by parent statute), violating constitutional provisions (including Fundamental Rights), being unreasonable (in the Wednesbury sense), or failing to comply with mandatory procedural requirements.

However, mere inconvenience to affected parties is not a valid ground. Administrative rules may cause inconvenience while remaining valid if within delegated powers and not arbitrary or discriminatory.

Question 7 (Natural Justice Exceptions)

In which of the following situations may the requirement of prior hearing be dispensed with?

(A) Emergency requiring immediate action (B) Complex legal questions involved (C) Large number of persons affected (D) Administrative convenience

Answer: (A) Emergency requiring immediate action

Explanation: Natural justice requirements may be relaxed in genuine emergencies requiring immediate action where delay would defeat the purpose. However, post decisional hearing should normally be provided even in emergencies.

Complexity of legal questions does not excuse hearing; it may actually require more careful hearing. Large numbers affected can be addressed through representative procedures, not hearing elimination. Administrative convenience is never a valid excuse for denying natural justice.

Question 8 (Wednesbury Unreasonableness)

The Wednesbury unreasonableness test requires that the decision must be:

(A) Merely unreasonable from the court’s perspective (B) So unreasonable that no reasonable authority could have reached it (C) Against the weight of evidence (D) Contrary to the court’s policy preference

Answer: (B) So unreasonable that no reasonable authority could have reached it

Explanation: Wednesbury unreasonableness is a high threshold. Lord Greene in Associated Provincial Picture Houses v. Wednesbury Corporation (1948) held that courts should only intervene if the decision is “so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could ever have come to it.”

This respects administrative discretion while checking abuse. Mere disagreement with the decision, or finding it against the weight of evidence, or contrary to the court’s policy preference, is insufficient for judicial intervention on irrationality grounds.

Question 9 (Landmark Administrative Law Cases)

In which case did the Supreme Court extend the principles of natural justice to administrative proceedings, not just quasi judicial proceedings?

(A) Ridge v. Baldwin (B) A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India (C) Maneka Gandhi v. Union of India (D) Mohinder Singh Gill v. Chief Election Commissioner

Answer: (B) A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India

Explanation: In A.K. Kraipak v. Union of India (1970 SC), the Supreme Court held that natural justice principles apply to administrative functions, not just quasi judicial functions. The traditional distinction between administrative and quasi judicial functions for determining natural justice applicability was effectively abandoned.

Ridge v. Baldwin, an English case, revived natural justice but dealt with dismissal of a chief constable. Maneka Gandhi expanded Article 21 interpretation. This case is fundamental to understanding natural justice’s broad scope in Indian administrative law.

Question 10 (Comparative Administrative Law)

Which of the following is NOT a feature of the French administrative legal system?

(A) Dual system of courts separating administrative and ordinary courts (B) Conseil d’Etat as the Supreme administrative court (C) Principle of Judicial Independence (D) Use of Stare decisis in administrative decisions

Answer: (D) Use of Stare decisis in administrative decisions

Explanation: The French droit administratif system features a dual court structure with separate administrative courts headed by the Conseil d’Etat. Judicial independence is maintained. However, France follows the civil law tradition, which does not recognize stare decisis (binding precedent) in the common law sense.

While French administrative courts consider previous decisions, they are not bound by precedent as in common law systems. This distinction between civil law and common law approaches is important in comparative administrative law.

How to Prepare Constitutional and Administrative Law for UGC NET?

Effective preparation requires combining the right resources with strategic study planning. The breadth of Constitutional and Administrative Law demands systematic coverage over weeks, not last minute cramming. Here’s how to approach your preparation efficiently.

Best Books for Constitutional and Administrative Law Preparation

Selecting appropriate study materials can significantly impact your preparation quality. Different books serve different purposes; understanding when to use which resource optimizes your study time.

Recommended Books for Constitutional Law

For comprehensive Constitutional Law understanding, M.P. Jain’s “Indian Constitutional Law” remains the gold standard. It covers all aspects in depth with detailed case law analysis. However, its length makes it suitable for thorough preparation over several months rather than quick revision.

V.N. Shukla’s “Constitution of India” offers more concise coverage while maintaining analytical depth. It’s particularly useful for understanding the constitutional text alongside judicial interpretation. For quick reference, keep a bare Constitution text handy; many UGC NET questions test exact Article knowledge.

D.D. Basu’s “Introduction to the Constitution of India” provides accessible coverage suitable for candidates beginning their constitutional law journey. It balances readability with comprehensive coverage.

Recommended Books for Administrative Law

I.P. Massey’s “Administrative Law” is the recommended comprehensive text for administrative law. It covers Indian administrative law with comparative perspectives and extensive case law analysis. The book’s treatment of natural justice and judicial review is particularly strong.

For examination focused preparation, S.P. Sathe’s “Administrative Law” provides clear conceptual explanations.

C.K. Takwani’s “Lectures on Administrative Law” offers accessible coverage suitable for building foundational understanding.

UGC NET Specific Guides and Question Banks

For UGC NET specific preparation, “UGC NET Law Guide” by Rukmesh covers all Paper II units with examination oriented focus.

“The Ultimate Guide to UGC NET (Law)” by Bhavna Sharma provides updated content including new criminal laws coverage.

Previous year question compilations from NTA’s official website are invaluable.

Creating an Effective Study Plan

A structured study plan ensures comprehensive coverage within available time. Whether you have three months or six months, discipline and consistency matter more than total hours invested.

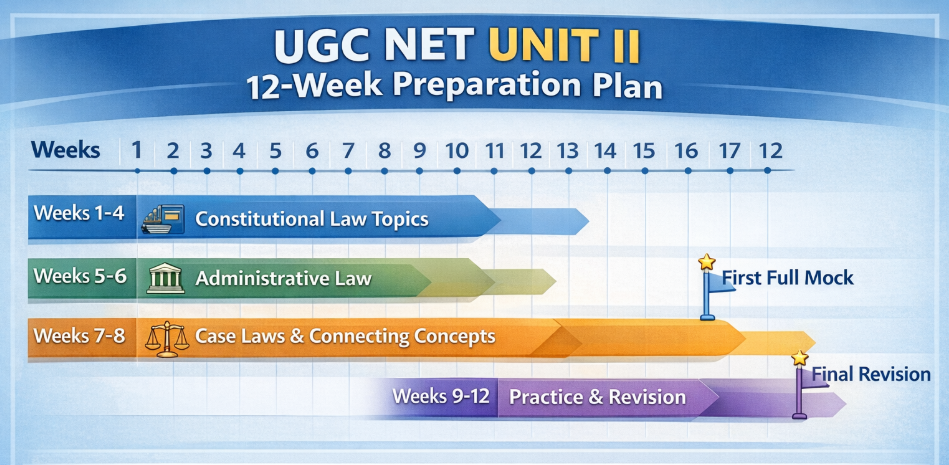

3 Month Preparation Strategy for Unit II

In a three month timeline, allocate approximately four weeks to Constitutional Law topics, two weeks to Administrative Law, two weeks to case law memorization and connections, and four weeks to practice and revision.

During Constitutional Law weeks, cover two to three major topics daily.

Begin with Fundamental Rights (most tested), proceed to Emergency Provisions, then distribution of powers and federal structure. Use M.P. Jain or Shukla for conceptual clarity; reinforce with previous year questions after each topic.

Administrative Law requires focused but intensive coverage. Natural justice principles and judicial review grounds appear almost every cycle. Master the juristic definitions, types of bias, and the Wednesbury test thoroughly.

6 Month Preparation Strategy for Unit II

A six month timeline allows deeper engagement with materials and more extensive practice. Spend the first two months building conceptual foundations through comprehensive texts.

The third and fourth months should focus on case law study and connecting concepts across topics. The final two months are for intensive mock tests and revision.

With more time, read M.P. Jain more thoroughly rather than relying solely on guides. Understand the evolution of constitutional doctrines through original case readings where possible.

This depth helps with comprehension based questions that test analytical understanding beyond mere recall.

Revision and Mock Test Strategy

The final month should prioritize revision and practice over new learning. Create concise notes on frequently tested areas: landmark cases, article numbers, constitutional amendments, natural justice principles, and judicial review grounds.

Attempt at least 15 to 20 full length mock tests before the examination.

After each test, analyze errors by categorizing them: conceptual gaps, careless mistakes, or time management issues. Focus revision on weak areas identified through mock analysis.

For Unit II specifically, practice matching questions (cases with principles, jurists with definitions), chronological arrangement questions, and comprehension based questions. These formats appear regularly and require specific preparation strategies.

Conclusion

Constitutional and Administrative Law is crucial for UGC NET Law Paper II, consistently yielding approximately 9 to 27 questions per cycle, marks that often determine qualification success. Question distribution varies by cycle and is based on candidate recollections/coaching analyses, as NTA does not officially release unit wise breakdowns.

This unit has a dual nature: Constitutional Law requires comprehensive coverage of Fundamental Rights, Emergency Provisions, power distribution, and landmark cases like Kesavananda Bharati; Administrative Law offers concentrated scoring through natural justice, judicial review, and juristic definitions.

The 20 sample questions here mirror actual UGC NET patterns based on previous year analysis. Practice them to identify recurring patterns in official papers, matching questions on bias types, chronological arrangements, and comprehension passages reflect what you’ll face.

These topics are interconnected: the Basic Structure Doctrine links to Fundamental Rights; natural justice echoes constitutional due process; judicial review bridges both subjects. Understanding these connections helps with application based questions testing integrated knowledge.

Prioritize high frequency topics first, ensure comprehensive coverage, and practice extensively using NTA’s official previous year papers. Build case law knowledge around examination patterns, not encyclopedic memorization.

In this competitive exam where margins matter, mastering Unit II provides significant advantage. Your preparation effort here directly impacts your final score and JRF prospects.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Constitutional Law more important than Administrative Law for UGC NET?

Constitutional Law typically generates more questions due to its larger syllabus coverage. However, Administrative Law questions are often more predictable, focusing on natural justice, judicial review, and definitions. Strategic preparation covers both; neglecting either risks losing certain marks.

Which topics in Constitutional Law are most frequently asked in UGC NET?

Fundamental Rights (especially Articles 14, 19, 21, 32), Basic Structure Doctrine, Emergency Provisions (Articles 352, 356, 360), distribution of legislative powers, and constitutional amendments appear most frequently. Questions on the Preamble and Directive Principles also feature regularly.

What are the most important Administrative Law topics for UGC NET?

Principles of Natural Justice (Audi Alteram Partem and Rule Against Bias), judicial review grounds (illegality, irrationality, procedural impropriety), and juristic definitions of administrative law appear almost every cycle. The June 2025 matching question on jurists and definitions illustrates this pattern.

Which case laws are essential for Constitutional Law preparation?

Kesavananda Bharati (Basic Structure), Maneka Gandhi (Article 21 expansion), S.R. Bommai (Article 356 limitations), Minerva Mills (Basic Structure reaffirmation), and E.P. Royappa (Article 14 arbitrariness test) are indispensable. Recent judgments like Kaushal Kishore v. State of UP (2023 SC)on Article 19‘s horizontal application are increasingly relevant.

Which case laws are essential for Administrative Law preparation?

A.K. Kraipak (natural justice extension to administrative functions), Gullapalli Nageswara Rao (official bias), Dimes v. Grand Junction Canal (pecuniary bias), Ridge v. Baldwin (natural justice revival), and Associated Provincial Picture Houses v. Wednesbury Corporation (irrationality test) form the core.

How should I balance preparation between Constitutional and Administrative Law?