Master UGC NET Reading Comprehension with proven strategies for all question types. Learn passage approaches, time management, and practice techniques to score more marks in the Reading Comprehension section.

Let’s talk about the 10 marks most UGC NET candidates waste without even realizing it.

You spend weeks mastering Teaching Aptitude models, cramming ICT acronyms, and memorizing research designs. Then exam day arrives, and there it is, a passage on something you’ve never studied, followed by 5 questions worth 10 marks. And suddenly, all that preparation means nothing.

This is Reading Comprehension. The great equalizer.

It doesn’t care if you’re a PhD scholar or a fresh postgraduate. It doesn’t reward the person who studied longest, it rewards the person who reads smartest. A literature student can score zero here. An engineering graduate can ace it. Why? Because Reading Comprehension isn’t testing what you know. It’s testing how you think.

The irony? While candidates obsess over units they can “study,” they completely ignore the one section that’s actually predictable. Yes, the passage will be new. And yes, NTA doesn’t follow a uniform pattern, the number of questions and their distribution keeps changing from exam to exam.

But here’s what doesn’t change: the question types themselves. The cognitive traps examiners set? Identical across years. The reading strategy that separates scorers from guessers? Totally learnable in 6 to 8 weeks.

This guide shows you exactly how to crack those patterns. Not by reading more, but by reading right. Not by memorizing passages, but by recognizing what each question type is really asking, whether NTA throws 3 questions at you or 7.

Ready to turn Reading Comprehension from a guessing game into your most reliable scoring section? Let’s begin.

UGC NET Paper I Reading Comprehension: Format and Structure

Before diving into strategies, you need to understand exactly what you are preparing for. The Reading Comprehension section in UGC NET Paper I follows a consistent format that has remained largely unchanged over the years.

Knowing this structure helps you build targeted skills rather than wasting time on unnecessary preparation. Once you understand the format, you can design your practice sessions to mirror the actual exam conditions.

Passage Length and Format

The Comprehension section in UGC NET Paper I typically presents a single passage ranging from 300 to 500 words. This passage is drawn from published material covering topics in social sciences, humanities, science, or current affairs.

The language is academic but accessible, similar to what you would find in quality newspaper editorials or university level textbooks.

The passage is presented as continuous text, usually divided into 3 to 5 paragraphs. Each paragraph typically contains one central idea supported by examples or explanations. Understanding this paragraph based structure is crucial because most questions can be traced back to specific paragraphs, making your search for answers more efficient during the exam.

Number of Questions and Marks Distribution

As per the official syllabus the Reading Comprehension section contains exactly 5 questions, with each question carrying 2 marks. This means the entire section is worth 10 marks out of the total 100 marks in Paper I. However it is not a uniform pattern followed by the NTA. The question distribution keeps on changing.

Since there is no negative marking in UGC NET, you should attempt all questions regardless of your confidence level. Even an educated guess has a 25% chance of being correct.

These questions typically cover a mix of question types: fact based, inference based, vocabulary, main idea, and tone questions. The distribution varies from exam to exam, but you can expect at least one inference question and one vocabulary question in most papers.

According to the official UGC NET syllabus, comprehension is listed as Unit III of Paper I, emphasizing the ability to understand written text and draw logical conclusions.

Skills Tested in UGC NET Reading Comprehension

The Reading Comprehension section is not just about reading fast; it tests specific cognitive abilities that the UGC considers essential for future educators and researchers.

Understanding what skills are being evaluated helps you focus your preparation on the right areas. Many aspirants make the mistake of simply reading more passages without developing the underlying skills that actually get tested.

Strong Vocabulary

Strong vocabulary is the foundation of good comprehension. When you encounter unfamiliar words in a passage, your understanding of the surrounding text suffers. The UGC NET Reading Comprehension section directly tests vocabulary through questions that ask you to identify the meaning of specific words as used in the passage.

These questions require you to understand words in context rather than just knowing dictionary definitions.

Building vocabulary for Reading Comprehension is different from general vocabulary building. You do not need to memorize thousands of obscure words. Instead, focus on academic vocabulary commonly used in social science and humanities writing.

Words like “paradox,” “inherent,” “implicit,” “substantiate,” and “corroborate” appear frequently in UGC NET passages.

Reading newspaper editorials from publications like The Hindu or Indian Express exposes you to this academic vocabulary naturally.

Text Analysis, Inference and Logical Reasoning

Beyond vocabulary, Reading Comprehension tests your ability to analyze text structure and draw logical inferences. Inference questions ask you to understand what the author implies without stating directly.

This requires reading between the lines and connecting ideas across paragraphs. The ability to identify the author’s tone, purpose, and underlying argument falls under this skill category.

Logical reasoning within Reading Comprehension means understanding cause effect relationships, identifying supporting evidence, and recognizing how the author builds arguments.

When a question asks “What can be inferred from the passage?” or “The author would most likely agree with which statement?”, you are being tested on analytical thinking.

These skills develop through deliberate practice where you actively question what you read rather than passively absorbing information.

Types of Reading Comprehension Questions in UGC NET Paper I

Mastering Reading Comprehension requires you to recognize different question types and apply the appropriate strategy for each. Not all questions should be approached the same way.

A fact based question requires you to locate specific information, while an inference question requires you to synthesize information from multiple sentences.

Knowing the question type before you search for the answer saves significant time and improves accuracy.

Literal or Direct Factual Questions

Literal questions are the most straightforward type in Reading Comprehension. They ask about information that is explicitly stated in the passage. The answer exists word for word or in close paraphrase within the text.

These questions typically use phrases like “According to the passage,” “The author states that,” or “Which of the following is mentioned in the passage?”

Fact based questions are your scoring opportunities. They require no interpretation, just accurate location of information. If you can quickly scan the passage and find the relevant sentence, you have your answer. Most aspirants find these questions easiest, but careless reading can still lead to errors.

How to Identify Fact Based Questions Quickly?

Look for question stems that reference the passage directly.

Phrases like “as stated in the passage,” “the author mentions,” or “according to the text” signal fact based questions.

These questions ask you to retrieve information rather than interpret it. The answer will match something written in the passage, either verbatim or in slightly different words.

Another indicator is when questions ask about specific details: names, dates, numbers, definitions, or lists mentioned in the passage.

If the question asks “Which of the following reasons does the author give for…” you are dealing with a fact based question. Recognizing this immediately tells you to scan for that specific information rather than analyzing the overall meaning.

Strategy for Answering Fact Based Questions

First, identify the keywords in the question. These are usually nouns or specific terms that you can search for in the passage.

Once you locate the keywords, read the sentence containing them plus one sentence before and after. The answer almost always lies within this three sentence window.

Do not rely on memory when answering fact based questions.

Even if you think you remember the answer from your first reading, go back and verify. The options are often designed to trick you with slight modifications of actual passage content. Verification takes only 10 to 15 seconds and prevents careless errors that cost you marks.

Inference Questions

Inference questions test your ability to understand what the author implies without stating directly. These questions are trickier than fact based questions because the answer is not explicitly written in the passage.

You need to combine information from different parts of the passage and draw a logical conclusion. The NTA UGC NET exam has increasingly included more inference based questions in recent years.

Inference questions use phrases like “It can be inferred that,” “The passage suggests,” “The author implies,” or “Based on the passage, one can conclude.”

When you see these phrases, shift your approach from searching for explicit statements to analyzing the overall meaning and underlying message.

The Three Line Rule for Finding Hidden Inferences

When facing an inference question, identify the topic or concept the question asks about. Then locate where this topic appears in the passage. Read three lines before and three lines after this location.

Most inferences can be drawn from this six line window because authors typically develop their implied meanings in close proximity to the stated facts.

If the inference involves the author’s overall attitude or the passage’s main argument, focus on the first and last paragraphs. Authors usually establish their position early and reinforce it at the end. The opening sentences often contain the thesis, while closing sentences often contain the logical conclusion the author wants readers to draw.

Vocabulary and Word Meaning Questions

Vocabulary questions ask you to determine the meaning of a specific word as used in the passage. The key phrase here is “as used in the passage.”

Many English words have multiple meanings, and the question tests whether you can identify the correct meaning based on context. Simply knowing the word’s dictionary definition is not enough.

These questions typically present the target word in quotes and ask which option best captures its meaning in the given context. The options often include the word’s common meaning alongside its contextual meaning, creating a trap for those who do not read carefully.

Using Context Clue Method for Unknown Words

When you encounter an unfamiliar word, do not panic. Look at the sentence containing the word and identify clues that suggest its meaning. These clues include synonyms nearby, explanations following the word, examples that illustrate the concept, or contrasting ideas that help define the word by opposition.

Read the sentence without the unknown word and ask yourself what meaning would make sense. Often, the surrounding context makes the meaning clear even if you have never seen the word before. After guessing the meaning, check which option aligns with your contextual understanding.

Common Vocabulary Traps to Avoid

The most common trap is selecting a word’s primary dictionary meaning when the passage uses a secondary meaning. For example, “gravity” usually means the force of attraction, but in a passage about serious matters, it might mean “seriousness” or “importance.” Always verify your choice against the passage context.

Another trap involves similar sounding options. Test makers often include options that sound right but have subtle meaning differences. Read all four options completely before selecting. The correct answer should fit seamlessly into the original sentence when you substitute it for the target word.

Main Idea and Central Theme Questions

Main idea questions ask you to identify the primary purpose or central argument of the passage. These questions test whether you understand the passage as a whole rather than focusing on isolated details.

Phrases like “The main idea of the passage is,” “The passage primarily discusses,” or “The central theme is” indicate this question type.

Answering main idea questions requires you to distinguish between the overall argument and supporting details. Many wrong options present ideas that are mentioned in the passage but are not the central focus. Understanding the difference is crucial for selecting the correct answer.

How to Quickly Identify the Central Theme?

The central theme usually appears in the first paragraph, often in the opening two sentences. Authors typically state their main point early and then spend the rest of the passage supporting it. Reading the first paragraph carefully gives you a strong hypothesis about the main idea.

Confirm your hypothesis by reading the last paragraph. The conclusion usually restates or reinforces the main idea. If the opening and closing paragraphs align around a common theme, you have likely identified the central idea correctly. The body paragraphs provide supporting evidence but rarely introduce the main theme.

Distinguishing Main Idea from Supporting Details

Supporting details answer “how” or “why” questions about the main idea. They provide evidence, examples, or explanations. The main idea is the overarching claim that these details support.

If an option describes something mentioned in only one paragraph, it is likely a supporting detail, not the main idea.

Ask yourself: “Does this option capture what the entire passage is about, or just one part?” The correct main idea should connect to every paragraph in some way. If you can identify a paragraph that does not relate to an option, that option is probably not the main idea.

Tone and Author’s Attitude Questions

Tone questions ask you to identify the author’s attitude toward the subject matter. Is the author supportive, critical, neutral, optimistic, or pessimistic? These questions test your sensitivity to language choices that reveal underlying attitudes.

Understanding tone helps you interpret the author’s intended message beyond the literal words.

Tone questions use phrases like “The author’s tone is,” “The author’s attitude toward X is,” or “The passage can best be described as.” The options are typically adjectives describing emotional or intellectual stances.

Identifying Positive, Negative, and Neutral Tone

Positive tone indicators include words of praise, optimism, and approval: “remarkable,” “promising,” “beneficial,” “innovative.”

Negative tone indicators include criticism, skepticism, and disapproval: “flawed,” “questionable,” “inadequate,” “concerning.”

Neutral tone maintains objectivity without emotional language.

Most UGC NET passages maintain an academic, somewhat neutral tone with subtle leanings.

Extreme tones like “angry,” “ecstatic,” or “despairing” are rare in academic writing. When options include extreme descriptors, they are usually wrong. Look for moderate tone descriptors that match academic writing style.

Common Tone Words You Must Know

Familiarize yourself with tone vocabulary commonly used in Reading Comprehension questions.

- Positive tones include: appreciative, supportive, enthusiastic, optimistic, laudatory.

- Negative tones include: critical, skeptical, dismissive, pessimistic, disapproving.

- Neutral tones include: objective, analytical, informative, dispassionate, impartial.

Mixed tones also appear: “cautiously optimistic” combines hope with reservation, “grudgingly admiring” combines reluctance with respect. When passages discuss complex issues, authors often hold nuanced positions that simple positive negative labels do not capture. Watch for these balanced tone options.

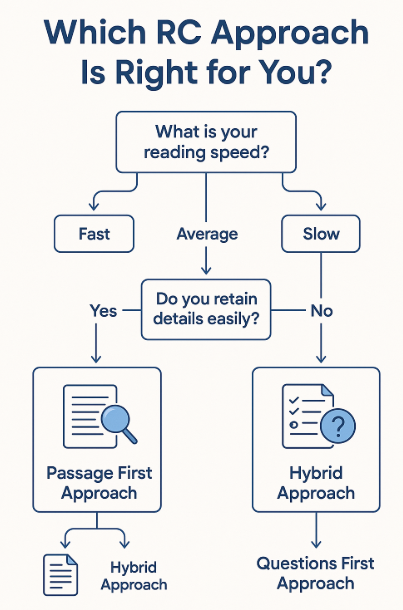

Best Reading Strategy for UGC NET: Questions First or Passage First?

One of the most debated topics in Reading Comprehension preparation is whether to read the passage first or the questions first.

Both approaches have merit, and the right choice depends on your reading speed and comprehension style. Understanding both methods allows you to choose the one that maximizes your performance or even combine them into a hybrid approach.

Questions First Approach (Most Recommended Method)

The Questions First approach, also called the QP method, involves reading all the questions before reading the passage.

This strategy gives you a roadmap of what information to look for, making your reading more purposeful and efficient. For most aspirants, especially those who are not exceptionally fast readers, this approach yields better results.

When you know the questions beforehand, your brain actively searches for relevant information while reading. Instead of trying to remember everything, you focus on specific details, concepts, and arguments that the questions target. This selective attention reduces cognitive load and improves both speed and accuracy.

Questions First Method: Ideal Scenarios

This method works best when you have average reading speed and tend to forget details from earlier paragraphs by the time you reach the questions.

If you often find yourself rereading the passage after seeing the questions, the Questions First approach eliminates this inefficiency.

It also works well when you are short on time. By knowing exactly what to look for, you can skim through less relevant portions of the passage and slow down only when you encounter information related to the questions. This strategic reading saves precious minutes.

Passage First Approach (For Fast Readers)

The Passage First approach, or PQ method, involves reading the entire passage before looking at the questions.

This traditional method works well for fast readers who can comprehend and retain information from a single reading. If you can read 300 to 500 words in under 3 minutes while understanding the content, this approach might suit you.

The advantage of reading passage first is that you develop a complete understanding of the author’s argument before encountering questions.

This holistic understanding helps with main idea and tone questions, which require grasping the passage as a whole rather than focusing on specific details.

Passage First Method: Ideal Situations for Use

Use this method if you are a naturally fast reader with good retention. If you typically remember key points from what you read without needing to take notes, the Passage First approach leverages your strength. Re reading wastes your advantage.

This method also works well when the passage is short or when you have ample time. In low pressure situations, taking time to understand the full context before answering questions can lead to more thoughtful responses.

How to Choose the Right Approach?

The best approach is the one that matches your natural reading style. Do not force yourself into a method that feels unnatural. Experiment with both approaches during practice and track your accuracy and timing for each. After 10 to 15 practice passages, the data will clearly show which method works better for you.

Consider your performance under pressure as well. Some people read well during practice but struggle during timed conditions. Test both approaches in exam like timed settings to make an informed decision.

Hybrid Approach: Paragraph by Paragraph Method

The hybrid approach combines elements of both methods. First, quickly scan the questions to know what you are looking for. Then read the passage paragraph by paragraph. After each paragraph, check if any questions can be answered based on what you just read.

This method works well for medium speed readers and for longer passages. It prevents the overwhelming feeling of reading a long passage without direction while also avoiding the need to hold all five questions in memory throughout your reading.

How to Tackle Different Types of Passages in UGC NET Reading Comprehension?

Not all passages are created equal. The approach that works for an argumentative passage might not work as well for a narrative one.

Recognizing the passage type within the first few sentences allows you to adjust your reading strategy accordingly. UGC NET passages typically fall into four categories, each with distinct characteristics and question patterns.

Argumentative Passages

Argumentative passages present a claim and support it with reasons and evidence. The author takes a clear position on a debatable topic and attempts to persuade the reader.

These passages are common in UGC NET because they test your ability to follow logical reasoning and identify the author’s stance.

Questions from argumentative passages often focus on the author’s main argument, the evidence used to support it, potential weaknesses or counterarguments, and the author’s tone toward opposing views. Prepare for inference questions that ask what the author would agree or disagree with.

Identifying Argumentative Structure

Argumentative passages typically begin with a controversial claim or question. The opening paragraph establishes what the author will argue. Look for thesis statements like “This paper argues that…” or “Contrary to popular belief…” These signal argumentative intent.

The body paragraphs present evidence: statistics, examples, expert opinions, or logical reasoning. Each paragraph usually supports one aspect of the main argument. The conclusion restates the thesis and may call for action or further consideration.

Finding the Author’s Position Quickly

The author’s position is usually clearest in the first and last paragraphs. If you need to quickly identify where the author stands, focus on these sections. The introduction states the position; the conclusion reinforces it.

Watch for opinion markers: “I believe,” “it is clear that,” “the evidence suggests,” “we must recognize.” These phrases directly reveal the author’s stance. Also note what the author criticizes or praises; this reveals position through evaluation.

Descriptive and Narrative Passages

Descriptive passages paint a picture of a person, place, event, or concept without arguing for a particular position. Narrative passages tell a story or describe a sequence of events. Both types emphasize vivid detail and chronological or spatial organization rather than logical argumentation.

Questions from these passages often ask about specific details, sequences of events, character motivations, or the significance of described elements. Fact based questions are more common here than inference questions.

Key Elements to Look For

In descriptive passages, identify what is being described and what qualities or features the author emphasizes.

Look for sensory details, comparisons, and evaluative language that reveals the author’s attitude toward the subject.

In narrative passages, track the sequence of events and the relationships between characters or elements. Note cause and effect relationships: what happened and why. The chronological structure means information appears in time order, making it easier to locate specific details.

Common Question Patterns

Expect questions asking “According to the passage, what happened after X?” or “The author describes Y as having which characteristic?” These are mostly fact based questions requiring you to locate specific information.

Main idea questions might ask about the purpose of the description or narrative: “Why does the author describe X in such detail?” or “What is the significance of the events described?” These require understanding the author’s intent beyond the surface content.

Expository Passages

Expository passages explain concepts, processes, or phenomena without arguing a position. They aim to inform rather than persuade. Scientific explanations, historical accounts, and technical descriptions fall into this category. These passages prioritize clarity and accuracy over stylistic flourish.

Questions from expository passages test your understanding of the explained concept: definitions, processes, relationships, and applications. Vocabulary questions are common because expository writing often introduces technical terms.

Extracting Key Information Efficiently

Focus on understanding relationships rather than memorizing facts. Ask yourself: What causes what? What is the main point being explained? How do the details support the main explanation? This comprehension focused approach serves you better than trying to remember every number or date.

When you encounter definitions, pay special attention. Expository passages often ask vocabulary questions about terms defined within the passage. The author’s definition matters more than any outside knowledge you might have.

Social Science and Humanities Passages

Social science and humanities passages discuss topics from sociology, psychology, philosophy, history, political science, economics, and related fields.

These passages are most common in UGC NET because the exam targets future educators and researchers in these disciplines.

The language tends to be academic but accessible, similar to what you would find in undergraduate textbooks or quality journalism covering social issues. Abstract concepts, theoretical frameworks, and discussions of human behavior characterize these passages.

Key Concepts Frequently Tested

Passages often discuss development (social, economic, human), governance and policy, education and learning theories, environmental issues, cultural phenomena, and contemporary social challenges. Familiarity with these broad themes helps you engage with passages more quickly.

Reading the editorial sections of newspapers like The Hindu or magazines like Economic and Political Weekly builds familiarity with social science discourse. This background knowledge does not replace careful reading but helps you process information faster.

Common Mistakes in Reading Comprehension

Even well prepared candidates lose marks due to avoidable errors. Understanding common mistakes helps you consciously avoid them during the exam. These errors are not about lack of knowledge; they are about flawed approach and execution.

Eliminating these mistakes can improve your score by 2 to 4 marks, often the difference between qualifying and falling short.

Reading the Entire Passage Word by Word

Many aspirants believe that careful, word by word reading leads to better comprehension. In reality, this approach slows you down without proportionally improving understanding. It also exhausts your focus before you reach the questions, leading to errors from mental fatigue.

The human brain processes meaning in chunks, not individual words. Reading word by word actually disrupts your natural comprehension ability. Strategic reading, which varies speed based on content importance, outperforms uniform slow reading.

How Word by Word Reading Wastes Time?

With 5 questions worth 10 marks as per the official syllabus, you should not spend more than 8 to 10 minutes on the entire Reading Comprehension section, however you must know that the question distribution keeps on changing.

Word by word reading of a 400 word passage takes 4 to 5 minutes, leaving insufficient time for answering questions carefully. This time pressure leads to rushed, error prone responses.

Additionally, word by word reading does not improve retention proportionally to time spent. Research shows that moderate speed reading with good comprehension beats slow reading for both speed and accuracy. Your goal is understanding, not pronunciation.

Answering Based on General Knowledge Instead of the Passage

This is perhaps the most dangerous mistake. When you know a topic well, you might answer based on your knowledge rather than the passage content. But the correct answer is always what the passage says, even if your outside knowledge suggests otherwise.

Test makers deliberately include passages where common knowledge contradicts the passage’s specific claims. They know well read candidates will be tempted to apply their knowledge. The trap catches those who do not stick to the passage.

The “Passage is King” Rule

Adopt this rule: for RC questions, the passage is the only source of truth. Even if you are an expert on the topic, pretend you know nothing beyond what the passage tells you. This mindset prevents you from projecting your knowledge onto the text.

When evaluating options, ask “Does the passage support this?” not “Is this true?” An option might be factually correct but not supported by the passage. Such options are wrong for RC purposes.

How Examiners Set Traps Using Your Assumptions?

Examiners include options that are generally true but not mentioned in the passage. They also include options that contradict the passage but align with common beliefs. Both trap candidates who bring outside knowledge into their answers.

Another trap involves extreme statements. The passage might say “many experts believe X,” but an option states “all experts agree on X.” The passage does not support “all,” making this option wrong despite being close to passage content.

Spending Too Much Time on One Difficult Question

When you encounter a challenging question, the temptation is to keep working until you solve it.

But spending 3 to 4 minutes on one question leaves insufficient time for others. In RC, all questions carry equal marks. Missing an easy question because you ran out of time is worse than guessing on a hard one.

Time management requires emotional discipline. Accept that not every question will feel certain. Your goal is maximum total marks, not perfection on every question.

The 90 Second Rule for RC Questions

Allocate approximately 90 seconds per question, including the time to locate relevant passage content. If you exceed 90 seconds without finding the answer, make your best guess and move on. You can return if time permits.

Track time during practice to develop this sense naturally. After enough practice, you will intuitively know when 90 seconds have passed. This internal clock prevents over investment in any single question.

Mark and Move On in These Scenarios

Move on when you have eliminated two options but cannot decide between the remaining two. Also move on if you have read the relevant passage section twice without finding clarity. Further reading rarely helps; you either understand or you do not.

Before moving on, make a mark on your rough sheet so you know to return if time permits. Select a tentative answer so that even if you do not return, you have attempted the question.

Ignoring Transition and Structural Words

Transition words signal relationships between ideas. Ignoring them means missing crucial logical connections.

These words tell you whether the author is continuing a point, contrasting with a previous point, or concluding an argument. Missing these signals leads to misunderstanding the passage structure.

Structural words are especially important for inference and tone questions. They reveal the author’s logical movement and attitude in ways that content words alone do not.

Signal Words That Show Agreement

Continuity words indicate that the author is building on a previous point: “moreover,” “furthermore,” “additionally,” “similarly,” “in the same way,” “likewise,” “also.” When you see these, expect the following content to support or extend what came before.

These words help you understand passage structure. If a question asks about the relationship between two paragraphs and the second begins with “furthermore,” you know the paragraphs share a supporting relationship.

Contrast Words That Change Direction

Contrast words indicate disagreement or qualification: “however,” “nevertheless,” “despite,” “although,” “but,” “yet,” “conversely,” “on the other hand.” These signal that the author is about to present a different perspective or limit a previous claim.

Contrast words are goldmines for understanding author attitude. If the author says “Many believe X. However, the evidence suggests Y,” you know the author supports Y over X. Missing “however” means missing this crucial positioning.

How to Prepare for UGC NET Reading Comprehension?

Preparation for RC is fundamentally different from other Paper 1 units. You cannot memorize your way to success. Instead, you must build skills through deliberate practice over time.

This section provides a structured preparation plan that progressively develops your speed, accuracy, and strategy application.

Daily Practice Routine for RC Mastery

Consistency beats intensity for skill development. Practicing 2 to 3 passages daily for two months produces better results than cramming 20 passages the week before the exam. Your brain needs time to internalize reading strategies until they become automatic.

Create a dedicated time slot for RC practice, preferably when your mind is fresh. Morning practice often works better than late night sessions. Treat this practice time as non negotiable preparation.

Week 1 to 4: Foundation Building Speed (3 to 4 Passages Daily)

During the first month, focus on reading more with less concern for timing. Practice 3 to 4 passages daily from various sources. After each passage, answer questions and check accuracy, but do not worry about speed yet.

The goal is developing comfort with different passage types and question formats.

Pay attention to your mistakes. Maintain an error log noting which question types you get wrong and why. This self analysis reveals patterns that guide your focused improvement.

Week 5 to 8: Speed and Building Accuracy (Timed Practice)

In the second month, introduce time pressure. Give yourself 8 to 10 minutes per passage (reading plus all questions). Track your completion time and accuracy for each practice session. You should see both improving over these weeks.

If accuracy drops significantly under time pressure, you are reading too fast. Find the speed at which you maintain 80% accuracy.

Gradually push this speed faster while maintaining accuracy. Quality over quantity in answers matters more than rushing through more passages.

Final Month: Mock Tests and Previous Year Papers

In the final month, practice with actual UGC NET previous year papers. These give you the most realistic preparation for exam conditions.

Take full Paper 1 mock tests to practice RC within the broader exam context. When you practice RC in isolation, conditions are different from actually allocating time within a 50 question paper. Full mocks build realistic time management skills.

Best Sources for RC Practice Passages

The quality of practice material matters. Practicing with passages too easy or too different from UGC NET style wastes your time. Choose sources that mirror the academic, moderate difficulty level of actual exam passages.

Newspaper Editorials: Which Sections to Read Daily

Editorial pages of quality newspapers provide excellent RC practice. The Hindu, Indian Express, and Hindustan Times editorials match UGC NET passage difficulty. Focus on editorials about education, social policy, environment, and governance, as these topics frequently appear in the exam.

Read one editorial daily and summarize the main argument in your mind. Identify the author’s stance, key evidence, and conclusion. This active reading builds the analytical skills RC questions test.

UGC NET Previous Year Papers

Previous year papers are your most valuable resource. They show exact passage difficulty, question types, and examiner preferences. Solving 10 to 15 years of previous papers exposes you to enough variety that exam day holds no surprises.

After solving previous papers, analyze patterns. Do certain question types recur? Do passages favor certain topics? This analysis informs your focused preparation and builds confidence through familiarity.

Other Competitive Exam RC Sections

CAT, GMAT, and GRE reading comprehension sections provide additional practice material. While slightly more difficult than UGC NET, practicing with harder material makes exam passages feel easier. UPSC CSE Prelims CSAT also has good RC passages at comparable difficulty.

Do not rely exclusively on other exams’ material. Use them as supplementary practice while keeping UGC NET previous papers as your primary source.

Vocabulary Building Strategy for RC Success

Strong vocabulary makes passages easier to understand and helps with vocabulary questions directly. Unlike general vocabulary building, RC vocabulary focuses on academic words common in social science and humanities writing.

High Frequency Words in UGC NET Passages

Certain words appear repeatedly in academic writing: “paradigm,” “nuance,” “inherent,” “exacerbate,” “mitigate,” “substantiate,” “corroborate,” “proliferate,” “unprecedented,” “pragmatic.” Compile a list of such words from your practice passages and learn them actively.

Focus on words that express relationships (causation, contrast, similarity) and evaluation (positive, negative, neutral judgments). These functional words help you understand passage structure beyond just content.

The 15 Words Per Day Method

Learning 15 new words daily is sustainable and effective. Write each word, its meaning, and a sentence using it. Review previous days’ words before adding new ones. This spaced repetition ensures long term retention.

Source your daily words from practice passages and vocabulary lists for competitive exams. Norman Lewis’s “Word Power Made Easy” remains a classic resource that builds vocabulary systematically.

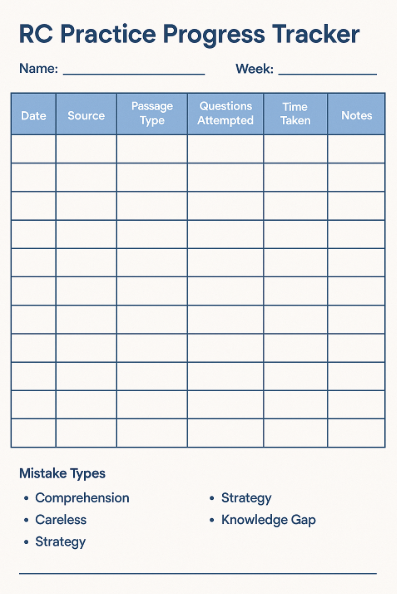

How to Track Your Progress and Identify Weak Areas?

What gets measured gets improved. Tracking your practice performance reveals trends that guide your preparation. Without tracking, you might repeat the same mistakes without realizing it.

Maintaining an RC Performance Log

Create a simple log recording: date, passage source, number of questions attempted, number correct, time taken, and question types missed.

Review this log weekly to identify patterns. Are you consistently missing inference questions? Struggling with humanities passages? Taking too long?

This data driven approach removes guesswork from preparation. Instead of vaguely feeling you need to “practice more,” you know specifically what needs work.

Analyzing Mistake Patterns

Categorize your mistakes: comprehension errors (misunderstood passage), careless errors (knew answer but marked wrong), strategy errors (right approach but wrong execution), knowledge gaps (vocabulary or concept gaps). Each category requires different solutions.

For comprehension errors, slow down and practice active reading. For careless errors, build verification habits. For strategy errors, revisit and practice the specific technique. For knowledge gaps, targeted learning fills the void.

Conclusion

Scoring full marks in UGC NET Reading Comprehension is absolutely achievable with the right strategy and consistent practice.

Unlike other Paper 1 units that require memorizing facts and concepts, RC rewards technique mastery and skill development.

Remember that success in RC comes from deliberate practice, not last minute cramming.

Start with understanding the question types and identifying which ones challenge you most.

Choose your reading approach based on honest self assessment of your speed and retention. Practice daily with quality materials, gradually introducing time pressure as your skills develop.

The Reading Comprehension section is perhaps the most “controllable” part of Paper 1. While Teaching Aptitude or Higher Education topics might surprise you with unexpected questions, RC passages play by consistent rules.

Master those rules through the strategies in this guide, and you will convert this section into a reliable source of marks.

Your next step is simple: download a few previous year papers and apply these strategies immediately. Track your performance, identify your weak areas, and focus your practice accordingly. Start today, and let RC become your scoring strength rather than an uncertain variable.

Frequently Asked Questions

How many questions come from Reading Comprehension in UGC NET Paper I?

As per the official syllabus the Reading Comprehension section contains 5 questions worth 2 marks each, totaling 10 marks. These questions are based on a single passage of 300 to 500 words. Since there is no negative marking, you should attempt all questions even if unsure about some answers. NTA occasionally adjusts section weightage slightly across shifts. It is advisable to check previous papers.

Is there a specific syllabus for Reading Comprehension in UGC NET?

There is no specific content syllabus because Reading Comprehension tests skills rather than knowledge. According to the official syllabus, Unit 3 covers “Comprehension” focusing on understanding written text. Passages can cover any topic from social sciences, humanities, science, or current affairs.

Should I read the passage first or the questions first?

For most aspirants, reading questions first works better. This approach tells you what information to look for, making your reading purposeful. However, fast readers with good retention may prefer reading the passage first. Experiment with both during practice and choose what gives you better results.

How much time should I spend on the RC section?

Aim to complete the entire RC section in 8 to 10 minutes: about 3 minutes for reading and 5 to 7 minutes for answering questions. This leaves sufficient time for other Paper I sections. Practice under timed conditions to build this time sense naturally.

What type of passages are typically given in UGC NET?

Passages typically come from social sciences and humanities: education, sociology, psychology, economics, history, environmental studies, and public policy. The language is academic but accessible, similar to quality newspaper editorials or undergraduate textbooks. Technical jargon is rare.

How can I improve my vocabulary for Reading Comprehension?

Build vocabulary through daily reading of newspaper editorials and learning 15 new words per day using flashcards. Focus on academic vocabulary: words expressing relationships (cause, contrast, similarity) and evaluation (positive, negative terms). Previous year passages provide the best vocabulary source. Focus on context based learning from RC passages in mocks.

Are inference based questions more common than fact based questions?

Recent UGC NET papers show increasing inference questions, now comprising about 30 to 35% of RC questions. Fact based questions remain significant at about 25%. The trend favors analytical questions over simple information retrieval. Prepare for both but expect inference questions.

Can I score full marks in RC without any special preparation?

While some naturally skilled readers score well without specific RC preparation, most candidates benefit significantly from strategy training. Understanding question types, practicing timed passages, and building systematic approaches typically adds 2 to 4 marks compared to unprepared attempts.

Which books are best for practicing Reading Comprehension for UGC NET?

UGC NET previous year papers are your best resource. For additional practice, Trueman’s UGC NET Paper 1 and Arihant’s guides provide passages at appropriate difficulty. Newspaper editorials from The Hindu offer free daily practice. Avoid overly difficult sources like GRE unless you find UGC NET passages too easy.

How do I handle passages on unfamiliar topics?

Do not panic when encountering unfamiliar topics. RC tests comprehension, not prior knowledge. Read more carefully, rely heavily on context clues for vocabulary, and stick strictly to passage content for answers. Your outside knowledge cannot help and might actually mislead you.

How many Reading Comprehension passages should I practice daily?

During active preparation, practice 2 to 3 passages daily. Quality matters more than quantity: analyze mistakes after each passage rather than rushing through many. In the final month, focus on previous year papers and full mock tests rather than isolated passages.

Do Reading Comprehension passages in UGC NET repeat from previous years?

Passages do not repeat verbatim, but topics and question styles recur. Practicing previous year papers familiarizes you with the difficulty level and examiner preferences. Expect similar question types and passage structures even though the specific content will be new.

Allow notifications

Allow notifications